Removal of teeth and surgical implantology

6.1 Dental extractions

Assessment for extraction

Indications for dental extraction

History and clinical examination

The assessment of the patient has already been described in Chapter 2. A thorough medical history prior to any surgical procedure is obviously essential. This will identify patients who may require special preparation prior to even the simplest dental extraction. Such patients may include those taking anticoagulant medication or those that have undergone irradiation, among many others (Chapter 3). The information obtained will also determine whether surgery should be undertaken by the general dentist or specialist and also the choice of setting. The home circumstances and availability of an escort may also be important if considering conscious sedation or general anaesthesia.

The history also includes questions about previous dental and surgical experience and assessment of patient anxiety (Chapter 4). The sex, general build of the patient or other factors may give an indication as to the expected ease or difficulty of the extraction. For example, an extraction is likely to be more difficult in heavily built men, elderly patients may have more brittle teeth and Afro-Caribbeans more dense alveolar bone, while child patients may have reduced access and less cooperation.

Radiological examination

Preoperative radiographs need not be taken prior to all extractions, but there are situations when radiographic assessment is essential to demonstrate root morphology, anatomical relationships or associated pathology (Box 6.1). Mandibular and maxillary third molar teeth are known to show a wide variability in root morphology, and so pre-extraction radiographs should always be taken. It is also essential to know the relationship of the inferior alveolar canal in the case of the lower third molar. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is indicated when an intimate relationship of the third molar and the inferior alveolar nerve canal is observed on plain film. In general, where any difficulty is anticipated, it would be wise to take a radiograph before rather than during the extraction, so that the procedure may be planned appropriately. Where a radiograph is judged to be necessary, a periapical view should be the first choice, although other films may be substituted or used in addition when indicated (e.g. panoramic or lateral oblique for lower third molar).

Surgical techniques

• Elevators: curved chisel-shaped instruments that fit the curvature of tooth roots; an elevator has a single blade.

• Luxators: similar to elevators but finer blade.

• Forceps: have paired blades that are hinged to permit the root to be grasped.

• Peritome: has a finer blade with which to sever the periodontal attachment and is preferred where it is important not to damage the bony support of the tooth, for example, when immediately replacing a tooth with a dental implant.

There are several different forceps extraction techniques described and some basic principles and guidance are required when learning. Forceps are used to disrupt the periodontal attachment and dilate the bony socket either directly, by forcing the blades between tooth and bone, or by moving the tooth root within the socket, or both. Once this has been done, the tooth may be lifted from its socket. The movements that are required to complete the extraction may be described as a preliminary movement to sever the periodontal membrane and generally dilate the socket, followed by a second movement to complete the dilation and withdraw the tooth. The first movement requires that force is directed along the long axis of the tooth, pushing the blades of the forceps towards the root apex. This force is then maintained during the second movement, which is dependent on the tooth root and bone morphology. If a tooth has a single round root, then it may be rotated. Where the buccal bone plate is relatively thin, it may be possible to distort it significantly by moving the forceps applied to the tooth root in a buccal direction. The second movement depends on the tooth and may be described as:

• upper incisors and canines: rotational

• upper premolars: limited buccal and palatal

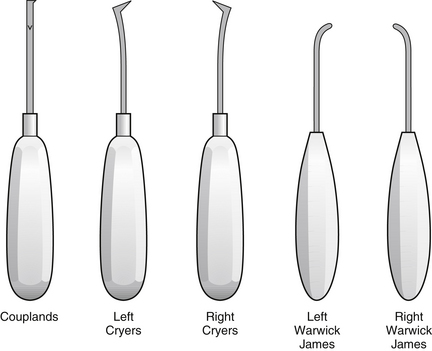

Alternative techniques for forceps movement are advocated by some, including a ‘figure of eight’ movement to expand the socket for molar teeth. Elevators may be used to carry out the first movement prior to completion of the extraction with forceps. Sometimes teeth and roots may be removed with elevators alone. There are many different designs of elevator (Fig. 6.1). The most commonly used are:

• Coupland’s elevators: a straight blade in line with the handle; available in three sizes referred to as 1, 2 and 3

• Cryer’s elevators: a triangular blade at right angles to the handle; available as a right and left pair

• Warwick James elevators: a small blade that is rounded at its tip rather than pointed; this is set at right angles to the tip in a right and left pair, but a straight Warwick James is also available.

It may be difficult to apply forceps to teeth that are outside of a crowded dental arch and elevators may be more appropriate for initiating the extraction or for the whole procedure. The applied force should be controlled and limited when using both elevators and forceps so that the soft tissues are not accidentally injured or the jaws fractured. Only with experience is it possible to know that the usual force is not producing the expected result, when further investigation is required with a radiograph (if not already available) or a transalveolar approach required.

Surgical removal of teeth

Teeth are surgically removed by a transalveolar approach. The procedure is described in Box 6.2.

Surgical flap design

The greater palatine artery and nerve lie in the palate (see Fig. 6.6 on p. 128) and can be safely retracted within an envelope flap to provide adequate access. The nasopalatine nerve and vessels emerge onto the palate via the incisive fossa in the midline just behind the maxillary central incisor teeth. The neurovascular bundle may have to be cut with a scalpel blade to allow a palatal flap to be raised and it is preferable to do this rather than to tear the bundle. Bleeding can be readily controlled with pressure for a short time and loss of sensation to the anterior palate is usually not of concern to the patient although it should be mentioned in advance of the procedure.

The two-sided flap is used when greater access is required. A relieving incision is usually made from the anterior aspect of the flap to maximise vision. A three-sided flap has anterior and posterior relieving incisions to provide the greatest mobility of the flap and access (see Fig. 5.9 on p. 96).

Postoperative care

Control of postoperative pain is important (Chapter 4). Some clinicians prescribe antibiotics if bone removal is necessary. There is some research evidence to support the use of corticosteroids to reduce postoperative oedema and trismus.

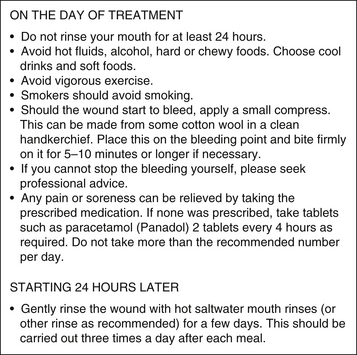

Patients should be given a written set of postoperative instructions (Fig. 6.2) and these should be also given verbally before the patient leaves.

Complications of dental extractions

Discomfort after the surgical trauma of dental extractions is to be expected and may be alleviated with an analgesic such as paracetamol or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen (Chapter 4).

Postoperative swelling

More significant swelling usually indicates postoperative infection or presence of a haematoma. Management of infection may require systemic antibiotics or drainage. A large haematoma may need to be drained. Less likely is surgical emphysema.

Excessive bleeding

Examination: Determine the source of the haemorrhage by sitting the patient upright (unless feeling faint) and using suction and a good light. This is commonly from capillaries of the bony socket or the gingival margin of the socket, or more unusually from a large blood vessel or soft tissue tear.

Achieve haemostasis: If the history has suggested a general cause, then local methods will not adequately result in haemostasis and the patient should be transferred to hospital where specialist haematological management is available. Otherwise the following techniques are used:

• Socket capillaries: pack the socket with an absorbable haemostat such as Surgicel oxidised cellulose.

• Gingival capillaries: suture the socket with a material that will permit adequate tension, such as Vicryl (or Surgicryl, or Polysorb), an absorbable braided synthetic material.

• Large blood vessel: ligate vessel, usually by passing a suture about the vessel and soft tissues.

Dry socket (alveolar osteitis)

• reassuring the patient that the correct tooth has been extracted

• irrigation of socket with warm saline or chlorhexidine mouthrinse to remove any debris

• dressing the socket to protect it from painful stimuli using resorbable Alvogyl paste, an iodoform dressing, or bismuth, iodoform and paraffin paste (BIPP) or lidocaine (lignocaine) gel on ribbon gauze, although this needs to be removed and replaced over 2 or 3 weeks.

Postoperative infection

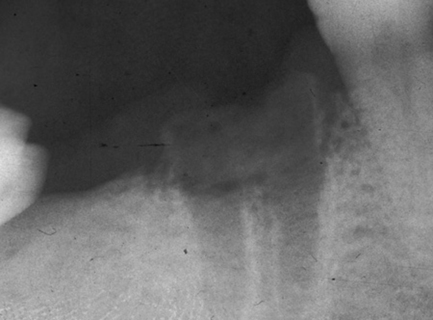

In some cases, sockets may become truly infected, with pus, local swelling and perhaps lymphadenopathy. This is usually localised to the socket and can be managed in the same way as a dry socket, although antibiotics may be necessary in some instances. A radiograph should be taken to exclude the presence of a retained root or sequestered bone (Fig. 6.3). Positive evidence of such material in the socket indicates a need for curettage of the socket.

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis (Chapter 5) is rare but may be identified by radiological evidence of loss of the socket lamina dura and a rarefying osteitis in the surrounding bone, often with scattered radio-opacities representing sequestra (see Figs 5.20 and 5.21 on p. 105 and 106).

Opening of the maxillary sinus

Creation of a communication between the oral cavity and maxillary sinus, an oroantral communication (OAC), may result during extraction of upper molar teeth. This is described in Chapter 7.

Loss of tooth

A whole tooth may occasionally be displaced into the maxillary sinus, when it is managed as for displacement of a root fragment, as described in Chapter 7.

A tooth may also be lost into the infratemporal fossa or the tissue spaces about the jaws, but this usually only occurs when mucoperiosteal flaps are raised.

Fracture of the maxillary tuberosity

Fracture of the maxillary tuberosity can result from the extraction of upper posterior molar teeth; it is described in Chapter 7.

Displacement of tooth into the airway

A chest radiograph is essential if a lost tooth cannot be found, to exclude inhalation.

6.2 Impacted and ectopic teeth

Assessment

Third molars: These usually erupt between 18 and 24 years but, frequently, eruption occurs outside these limits. One or more third molars fail to develop in approximately one in four adults. Impaction of third molars predisposes to pathological changes such as pericoronitis, caries, resorption and periodontal disease.

History and clinical examination

The patient may have noticed that a tooth is missing or this may not be apparent until observed at a routine dental examination. It is unusual for unerupted teeth to cause pain unless there is associated infection. The signs and symptoms of pericoronal inflammation are described in Chapter 5. Pericoronitis can be associated with any impacted tooth but is of particular concern when it involves the mandibular third molar because of the greater potential to spread via the tissue spaces and compromise the airway.

Radiological examination

• periapical, dental panoramic tomography (DPT) (or lateral oblique) and CBCT when indicated for lower third molars

• DPT (or lateral oblique, or adequate periapical) for upper third molars

• parallax films (two periapicals or one periapical and an occlusal film) for maxillary canines and CBCT when indicated such as when concerned about adjacent tooth resorption on plain films

• periapical and true occlusal radiograph for mandibular second premolar; a DPT (or lateral oblique) should be used if the periapical does not image the whole of the unerupted tooth.

Radiological assessment of impacted teeth should cover:

• type and orientation of impaction and the access to the tooth

• alveolar bone level, including depth and density

• periodontal status, adjacent teeth

• relationship or proximity of upper teeth to the nasal cavity or maxillary antrum

• relationship or proximity of lower teeth to the interdental canal, mental foramen, lower border of mandible.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses