Chapter 6

Non-Pharmacologic Approaches in Behavior Management

The previous chapters of this volume have focused on the child patient and the family. The remaining chapters deal specifically with techniques or strategies of behavior management which are used in the practice of dentistry for children.

The present chapter is devoted to non-pharmacologic approaches that are commonly used by dentists today. Most of these methods have evolved from generations of dental practitioners. Consequently, some of the references may seem historic, but they are still valid today. The methods in this chapter are extremely important because they are the basis for behavior management. If a child’s behavior cannot be managed, then it is difficult, if not impossible, to carry out any dental treatment. Behavior management is therefore one of the cornerstones of pediatric dentistry (Roberts et al 2010).

Many of the psychological terms used in this chapter are derived from learning theory. Learning theory is an all-embracing term for a body of psychological research that describes how people modify their behavior patterns as a result of personal experience or the experiences of a role model. In the language of learning theory, learning is the establishment of a connection or association between a stimulus and a response. It is often referred to as S-R theory.

In the original edition of this book, this chapter contained a section on learning theory. However, little has changed in this area in the past forty years and that section is omitted in the present edition. Instead, to be more relevant and practical, the chapter will interweave dentistry and psychology.

The importance of behavior management and its relationship to psychology has resulted in considerable coverage of the topic in the literature. Some are anecdotal writings. Some are based on psychological principles. Some are controlled studies. Some survey professional practices. Together, they provide a wealth of information. To organize and present the chapter in a meaningful way, and include the pertinent non-pharmacologic literature, it is divided into five parts: getting to know your patient, pre-appointment behavior modification, effective communication, non-pharmacologic clinical strategies, and retraining.

1. Getting To Know Your Patient

This section deals with getting to know new child patients. With all of these procedures, the primary goals are to: (1) learn about patient and parent concerns, and (2) gather information which enables a reasonably reliable estimate of the child’s cooperative ability.

Knowing as much as possible about the new patient prepares the dentist to deal with new patient situations in a meaningful way. Information collection begins at the first contact. Assuming that a parent telephones the dental office for a child’s appointment, the receptionist begins to create a record. The important demographic information is usually recorded on a card or computer. However, an astute receptionist will determine who referred the child patient, why the child has been referred to the office, and whether or not this is the child’s first dental visit. The responses to these questions can be very enlightening.

Once a new patient arrives in an office, dental teams conduct inquiries in two ways: (1) using a paper and pencil questionnaire completed by a parent or caregiver, and (2) by directly interviewing the child and parent. In some offices, one method may predominate, while in others, a combination of techniques is used.

Paper-and-pencil questionnaires.

Written questionnaires can be important tools for gaining information because probing questions can uncover critical facts about a family’s child-rearing practices, a child’s school experiences, or a child’s developmental status. Rather than including lengthy lists of questions that can be found in other sources, those items that have been found to be most helpful in clinical situations are shown in Table 6-1. Questions such as these provide some clue or insight into a child’s background.

The first question pertains to the intellectual capacity of the child. If “slow learner” is checked, then it is necessary to explore the matter further with the parent. The other four questions have direct clinical relevance (Wright and Stigers 2011). The question related to the child’s medical experience is from the investigation of Martin et al. (1977) and it relates to the child’s history with physicians. Much has been written about the relationship between past medical history and a child’s cooperative behavior in the dental environment. It seems the influential feature is the quality of medical contacts. That is, if a child relates positively to a physician and is well-behaved, there is a relatively good chance for cooperation at the dentist.

With respect to the response to the medical question, there is another factor worthy of consideration. To the very young child, the term “doctor” means a physician, and an appointment at the doctor’s office, whether physician or dentist, is all the same. The child generalizes the past experience. When the basis for generalization involves a language label, it is called “mediated generalization.” To the child approaching school age, language labels form the basis for many generalizations; hence the importance of word selection.

Table 6-1. These are clinically relevant questions that can be copied into the health history form.

| How do you consider your child is learning? | □ advanced in learning □ progressing normally □ a slow learner |

| How do you think your child has reacted to past medical experiences? | □ very well □ moderately well □ moderately poorly □ very poorly |

| How would you rate your own anxiety (nervousness, fear) at this moment? | □ high □ moderately high □ moderately low |

| Does your child think there is anything wrong with his/her teeth such as a chipped or decayed tooth, gumboil? | □ yes □ no |

| How do you expect your child to react in the dental chair? | □ very well □ moderately well □ moderately poorly □ very poorly |

The next question asks parents to rate their own anxiety. At least five studies in the 1970s documented a significant relationship between mothers’ anxieties and their children’s cooperative behaviors in the dental office. While at that time mothers primarily accompanied their children to the dental office, many fathers or both parents now bring children for dental appointments. Since the paternal role has yet to be explored, the clinician can only speculate at this time that fathers’ responses, like mothers’ responses, will be similarly correlated.

The fourth question asks whether the child believes that there is anything wrong with their dentition. An affirmative response indicates that something has been identified to the child and, consequently, apprehension is likely to be greater (Wright and Alpern 1971).

The final question emphasizes the role of parents as legitimate members of the Pediatric Dental Treatment Triangle in that they can predict their children’s cooperativeness with a high degree of accuracy. This question was found to be highly significant in studies by Martin et al. (1977) and Johnson and Baldwin (1968).

After reviewing the questionnaire responses, it is possible that the clinician may be concerned that the child will be uncooperative. Forehand and Long (1999) have referred to some uncooperative children as strong-willed. They are often described as being independent, persistent, and confident. While qualities such as these are quite positive, most strong-willed children can also be stubborn, argumentative, and defiant, leading to non-compliance. In an effort to learn more about these children, the questionnaire in Table 6-2 was developed based on the work of Forehand and Long. This questionnaire can be provided as a supplementary set of questions after examining the initial responses.

Table 6-2. Situations in which uncooperative children may display problems. Adapted from Forehand, R. and Long, N. Pediatr Dent 1999:21, 463–468.

| Situations in which strong-willed children often display problems |

Situations:

|

In the above situations:

|

Many of the foregoing questions came from behavioral science research that is now more than forty years old. Little research of this type is conducted in pediatric dentistry these days, so there is little new material to call upon. Nonetheless, the clinician should give serious consideration to incorporating such questions into a behavioral or health questionnaire. The list of questions is potentially endless, but that would be impractical. These questions have proven to be worthwhile. Careful scrutiny of the responses can tip off the astute clinician to a potential behavior problem.

The Functional Inquiry

In medical practice, a functional inquiry is a series of symptom-related questions posed in a personal interview that elicit new information and obtain further details about a presenting problem. In pediatric dentistry, it is used to learn about dental problems, explore the behavior of the new child patient, understand the parent’s attitude, and assess the potential for patient and parent compliance. The paper-and-pencil questionnaire offers a starting point. It provides general information and clues, and it guides the functional inquiry. To begin, consider the first question related to learning efficiency. If a parent has indicated that the child is a “slow learner,” more factual information is necessary. A leading question might be, “Is your child in a special class or special school?” Knowing that the child attends a special education class or school can offer a clue about the functioning level of the patient. If the child is behind in school or in a special program, then slow learning is an important part of the patient’s profile. The child may have to be guided through dental experiences more slowly, with clear, concrete, repeated explanations and visual aids. Conversely, a parent may indicate that a child is “advanced in learning.” The child may attend a school for the gifted. An important part of managing bright children often involves giving detailed explanations, catering to their curious natures.

For very young patients, two interesting questions are “What time does your child go to bed?” and “Is your child toilet trained?” If a child goes to bed at a regular hour, such as 7:00 p.m. or 8:00 p.m. and is toilet trained by the age of twenty-four to thirty-six months, the implication is that child-rearing practices in the home are structured. On the other hand, a three- to four-year-old child who does not go to bed as scheduled or who is not toilet trained arouses the experienced clinician’s suspicion about the home environment. Is the parent overly permissive? Is the child’s behavior generally non-compliant? More information can be obtained through the questionnaire in Table 6-2.

There is no limit to the depth of the functional inquiry, but if it is to be productive, questioning must be thoughtful. The information on the questionnaire helps to make this efficient. Other avenues to be explored include rewards and reinforcement in the home environment. These may provide some insight into the type of behavior management techniques that would be acceptable to the parent. Learning in advance that a parent does not believe in physical punishment can prevent a future confrontation if aversive techniques are employed.

Recall Patients

The discussion so far has been directed toward the new child patient. However, consider the case of this recall patient.

Case 6.1, Discussion: This case points out that functional inquiries are not limited only to new patients. When children have been patients for a long time, situations change and a periodic history review is in order. Based upon her father’s remarks, the child was quite anxious. If the dentist had known about Susan’s emotional state, she might have managed her differently or spoken to her about the problem. How was the dentist to know?

A recall history review is not as detailed as a new patient inquiry. It is generally conducted with a written questionnaire that provides an update on administrative information and health history. However, there are other questions to be asked, as shown in Table 6-3. The first question asks about oral hygiene. If a parent notes that the home care is adequate and, on examination, the child’s oral hygiene appears neglected, something is wrong. It may be that the parent’s expectations differ from those of the dentist. In this instance, consultation is necessary to re-establish hygiene goals. Or it may be that the child attends to the oral hygiene but requires further instruction.

Table 6-3. Responses to these questions can be helpful when updating the health history. They can alert the dental team to a potential problem.

| How do you think your child has maintained his/her oral hygiene? □ good □ fairly good □ not very well □ poor |

| Does your child have concerns about coming for this dental appointment? □ no anxiety □ a little anxiety □ anxious |

The second question is a behavioral one. If a child really approaches the office with fear, after being a patient in the office for several years, the dental team must make every effort to reduce the fearfulness over future appointments. A good way to begin is by asking “Were you nervous coming here today?” Children are usually truthful and will confirm or deny the suspicion. “Tell me why.” Sometimes the answer is simple: “I don’t like the taste of that (fluoride gel).” Many dentists keep several fluoride flavors in the office and can reply, “We have several kinds here. Today, you choose one. We will find one that you like.” The point is—as in Susan’s case—important information may be missed or problems undiscovered. The Pediatric Treatment Triangle variables are constantly changing and the astute clinician keeps patient information up-to-date.

2. Pre-Appointment Behavior Modification

Psychologists have developed many techniques for modifying patients’ behaviors by using the principles of learning theory. Behavior modification, sometimes called behavior therapy, may be defined as the attempt to alter human behavior and emotion in a beneficial manner and in accordance with the laws of learning theory (Eysenck 1964). These laws state that rewarded behavior tends to occur more often in presence, and unrewarded or punished behavior tends to be extinguished or disappear. Behavior therapists use various conditioning techniques to effect behavior changes. In this section, pre-appointment behavior modification refers to anything that is said or done to positively influence a child’s behavior before entering the dental operatory. In recent years, some of the methods employed include pre-appointment mailings, audiovisual modeling, and patient modeling.

Why use pre-appointment behavior modification? Dental anxiety represents a general state in which the individual is apprehensive and is prepared for something negative to happen (Klingberg 2008). It persists in our society. In a recent survey of 583 children nine to twelve years old, only 64% reported liking their last dental visit, while 11% didn’t like their visit and 12% were afraid to go to the dentist (AlSarheed 2011). With data like this, it is apparent that dental anxiety remains a common problem. It appears to develop mostly in childhood and adolescence (Locker et al. 2001). Consider the following scenario and what can be done to prevent it.

Case 6.2, Discussion: There are many possible reasons for Sally’s behavior. Her apprehension may have originated in the family unit. It may be caused by (1) behavior contagion, (2) threatening the child with the dentist as a punishment, (3) well-intentioned but improper preparation, (4) discussing dentistry problems within earshot of the child, or (5) sibling attitudes. The question is, what can be done to ease the child’s introduction to dentistry?

Pre-appointment contact

Many parent and child concerns can be alleviated. Pre-appointment contact can provide directions for preparing the child patient for an initial dental visit and, therefore, increase the likelihood of a successful first appointment. It also can diminish a parent’s apprehension. The sequence of events in many dental offices is: (1) the parent phones to make an appointment, (2) the appointment is made for some time in the future, and (3) the parent is contacted as a reminder the day before the dental appointment. Years ago, Tuma (1954) suggested sending a pre-appointment letter explaining what is to be done at the first visit. He hinted that this could modify the behavior of some children. In addition to serving as an appointment reminder, it established good public relations. He explained that child management in dentistry was based on sound principles of psychology, and he suggested rewards for good behavior or as tokens of affection—not as bribery. He implied that rewards for negative behavior only reinforced it and established bad habits. Thus, Tuma explained basic pediatric dentistry management techniques in psychological terms to parents.

Following up on Tuma’s suggestion, Wright et al. (1973) conducted a randomized, controlled study that demonstrated the beneficial effect of the pre-appointment letter. They mailed these letters to mothers of children three to six years of age who had appointments for first dental visits. The behavior of these children was compared with that of another group who had not received letters. As a result of the contact, children were better prepared by their mothers for their dental visits and were more cooperative. This was especially true for children three to four years old.

A simple letter can do much to relax a mother and help her prepare her child for the dental visit. In the study of Wright et al. (1973), mothers acknowledged their appreciation of the dentist’s thoughtfulness. They welcomed the concern for their children. The demonstrated effect is of great importance to the clinician. It reduced maternal anxiety and favorably affected the patient’s dental office behavior. Box 6.1 is a sample of the letter.

Nowadays, parental anxiety still needs to be considered, and new technology offers different options for pre-appointment contact. Many pediatric dentists have web sites, and a pre-appointment letter can be put on the site. Many patients provide their e-mail addresses to the dental office, and letters can be sent directly to them. Other technology software programs such as TeleVox® (®TeleVox Software Inc.) enable practices to send pre-appointment reminders and instructions to ensure parents remember and are well-prepared for appointments with their dentist. These programs can leave the information in various languages.

The work of Bailey et al. (1973) has also supported pre-appointment contact. By comparing maternal and child anxiety levels, they observed that a youngster exposed to a parent’s positive attitude toward a dental visit reacted more positively. Behavior was better for children prepared properly by parental discussion. It appears, then, that if the elements of surprise and lack of information are removed by parent preparation, children are more likely to cooperate.

Recommendations for many types of pre-appointment mailings have been made. Correspondence has run the gamut from the simplest welcoming letter to bombarding the mailbox with all manner of mailings. These have included pre-appointment questionnaires, dental society information flyers, commercial booklets, complicated statements of office policy, and even dental comic books. Numerous mailings can make too much of the first dental visit. Over-preparation can confuse the parents or provoke anxiety. Thus, the final effect of some of these approaches may be opposite the intention. The uncomplicated pre-appointment letter welcomes the patient, spells out the basic, first-appointment procedure avoiding dental terminology, and generally states the philosophy of good dental health care. This is sufficient.

Audiovisual modeling

This strategy can be applied before the appointment and in the clinic. The social learning theory proposed by Bandura (1977) has become perhaps the most influential theory of learning and development. While rooted in many of the basic concepts of learning theory, Bandura believed that direct reinforcement could not account for all types of learning. His theory added a social element, arguing that people could learn new information and behaviors by watching others. Factors involving both the model and the child patient can play a role in the success of observational learning (modeling). The child has to pay attention, remember what was observed, reproduce the behavior, and have good reason (motivation) to want to adopt the behavior. Without these factors, observational learning becomes ineffective.

Since the child must pay attention, anything that detracts attention will have a negative effect on observational learning. If modeling by audiovisual means in the dental office, a staff member should be present to direct the child’s attention to the model.

The ability to store information is also an important part of the learning process. Retention can be affected by a number of factors, so it is helpful if the staff member points out key parts of the presentation. The staff may question the child to reinforce the learning. Later, it is vital for the child to recall information and act on the observational learning. Once the child has paid attention to the model and retained the information, he should be led to the operatory with the parent. The procedure in the operatory should follow the model as closely as possible so that the child can actually reproduce the behavior.

Finally, for observational learning to be successful, the child has to be motivated to imitate the behavior that was modeled. Reinforcement plays an important role in motivation. For example, if a child sees a departing patient praised for their good behavior and given a prize, that motivates the new patient.

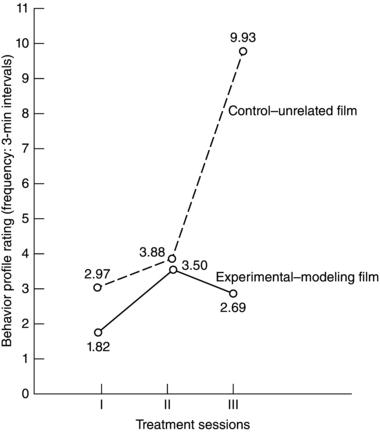

During the 1970s there were at least eight investigations into the merit of using videotaped modeling. Most of these studies used different procedures. For example, some had an assistant working with a child, while others left the child alone. The videotape presentations differed. As a consequence, results from these studies were mixed. A most supportive study was that of Malemed et al. (1975). They divided children between five and eleven years of age into two groups. One group viewed an unrelated film and the other watched a modeling film. Their results, which are summarized graphically in Figure 6-1, demonstrate the benefit of modeling.

Figure 6-1. The graph shows mean behavioral differences. The higher behavior profile rating indicates less cooperation. Note the wide difference in behavioral profile ratings between the two groups. Adapted from Melamed, B.G. et al. J Dent Res 1975: 54, 797.

Greenbaum and Melamed (1988) contend that research on modeling indicates that this technique offers dentists a means of reducing fear in child patients of all ages. They recommend it for children who have had no prior exposure to dental treatment. They further suggest that with videotape technology, the practitioner has the means to incorporate patient viewing of pre-recorded modeling tapes as part of the usual waiting period. Such a procedure creates a prepared patient, and the dentist will spend less time in behavioral management tasks.

Audiovisual modeling has several advantages. Since it is a “canned” presentation, nothing inadvertently creeps into the presentation that could influence the child negatively. However, an audiovisual presentation has two obvious disadvantages: (1) there is expense, as it requires special equipment and space, and (2) unless the presentation is developed by the dentist, it can be impersonal. For these reasons, some practitioners prefer live models.

Live models

There are three types of live models in a general practice: siblings, other children, and parents. Research by Ghose et al. (1969) evaluated the benefit of sibling models. The study concentrated on the effect of siblings on three- to five-year-old children without previous dental experiences. Sibling pairs entered the clinical area together, and the older child was examined first. Next, the younger child was examined while the older child observed. Similarly, dental prophylaxes and radiographs were performed for the children. At a second visit, a local anesthetic was administered and a restoration was completed. Sibling pairs serving as a control group were examined and treated separately. The study concluded that the presence of the older sibling had a favorable effect on the behavior of younger child at the first visit (Figure 6-2). The presence of a big brother or sister also seemed to maintain or even improve the younger child’s behavior during subsequent visits. Recall appointments in particular provide an excellent modeling opportunity for children (similar to parent recall appointments).

Using non-related children as models is also beneficial. Investigating this strategy, White and colleagues (1974) employed an eight-year-old model for children four to eight years of age. They divided subjects into three groups and compared the beneficial effects from either a modeling or a desensitization approach, with a control group having no preparation. They observed less avoidance behavior with both experimental groups and found that those children with the model seldom asked for a parent to be present. Similar results in the clinical setting were described by Adelson and Godfried (1970). They emphasized that the model was given a high status and rewarded for good behavior in the presence of the observing child.

Figure 6-2. The older sibling models for the younger one. Both children learn when an explanation is provided by the dentist.

The merits of modeling procedures using audiovisual or live models are recognized generally by psychologists. The merits are as follows: (1) stimulation of new and positive behaviors, (2) facilitation of behavior in a more appropriate time, (3) decrease of fear-related, inappropriate behavior, and (4) extinction of fears. These procedures offer the clinician some interesting ways to modify children’s behaviors before they are seated in the dental chair. Unfortunately, in the years since the 1970s, there has been little behavioral science research on this subject. Hopefully this area will be visited again in the near future.

3. Effective Communication

Although communication can occur in different ways, most non-pharmacological strategies are highly dependent upon verbal communication. There are many facets to good verbal communication.

Establishing communication

It is widely agreed that the first objective in the successful management of a young child is to establish communication. By involving a child in conversation, a dentist not only learns about the patient, but also relaxes the youngster. There are many ways to initiate verbal communication.

Case 6.3, Discussion: Jimmy responded to Dr. A.’s questions but was not actively involved in communicating. Dr. A. was in a hurry “to get to the mouth.” Welbury et al. (2005) refer to this type of communication as a preliminary chat. They suggest initiating conversation with non-dental topics. Many young children are very proud of their new clothing and they like to be asked about it. Older children often wear team sweaters, school crests or group uniforms (e.g., Brownies, Cubs, Beavers), and they like to be questioned about their activities. Whatever the ploy for initiating a conversation, questions should be phrased so that a child cannot offer a simple “yes” or “no” reply. Next, ask an open-ended question such as “What are those badges for?” This tends to establish communication. The process of drawing a child out and into communication with others around them is referred to as externalization. If other children in the family have attended the office previously, there should be information such as siblings’ names, pets, schools, or hobbies to call upon. This makes the initial questioning much more personal.

Children are often shy and reluctant to talk when they are first exposed to a new experience and to new people. When they have gained confidence and are comfortable in the unfamiliar environment, they will usually speak more freely. During the first dental visit they may speak more readily to a dental assistant. This enables the dentist to listen and make an evaluation of the comprehension and emotional maturity of the child.

Message clarity

A common theme throughout the literature in pediatric dentistry is that effective communication is essential to the development of a trusting relationship with the child patient. It is a critical requisite for the pediatric dentist in gaining cooperation (Nash 2006). To be effective, the message has to be clear. To ensure clarity, be certain that the child is addressed at the appropriate level of comprehension. This can be easily overlooked. Consider this example.

Case 6.4, Discussion: Two aspects of this case are noteworthy. First, the patient was four years old and the message may not have been understood. Dentists sometimes fail to communicate effectively (Chambers 1976). That may have been the problem in this case. If we say to a child “Open your mouth” or “Climb up into the chair,” the child likely will understand the instruction. But when the dentist said, “Sit perfectly still. This will only take a minute.” Dr. B. probably thought that the instructions to Jenny were clear and that good communication was established. That assumption may be incorrect. It is possible that the child did not truly understand what was meant by “sit still,” and it is probable that she had no concept of what constitutes a minute because she began moving after twenty seconds. Second, when the instructions were given on the first two occasions, they were delivered in a calm voice. On the third occasion, a firm displeased tone seemed to gain the result and the child was still. This is known as voice control.

There are other ways to deal with this situation. Dr. B. could have been more explicit and explained the problem to the child. “Jenny, the tooth that I am going to fix is way back here,” he could have said, pointing to the tooth. “I need you to help me. This is very important. If your head moves, even a little, then your tooth moves too. If you move your legs, it moves your head and your head moves the tooth. Try not to move your head, your arms or your legs while I am working on the tooth. I am going to count out loud and when I finish counting, we will be done.” By stressing the importance, the child’s awareness of the situation may be enhanced. By asking her to help, she is a member of the team.

Clarity only occurs when the message is understood in the same way by the sender and the receiver. There has to be a “fit” between the intended and understood messages. For children with limited vocabularies, more detailed verbal communication is often needed, and sometimes it has to be supplemented in other ways. Consider a common experience in the home environment. A three-year-old approaches the hot stove. Her mother says, “Go away, its hot.” If the child does not understand the meaning of hot, the she may return again. On the other hand, if the mother clarifies the verbal command and supplements it by picking up the child, placing the hand near the hot plate, and explaining that “hot hurts,” the message becomes clearer. An analogy in pediatric dentistry is the three-year-old who lifts a hand to the mouth while the dentist is using an explorer. Saying “put your hands down” gives a command, but the child may not pay much attention to it. In effect, it scolds the child. Demonstrating the sharpness of the instrument and telling the child to keep his hands down in order not to get hurt is more effective communication.

To improve message clarity with young children, pediatric dentists and their office personnel have to use euphemisms sometimes. These are non-offensive word substitutes. For most pediatric dentists, euphemisms are like a second language. The following is a small glossary of word substitutes that can be used to explain procedures to children.

| Dental Terminology | Word Substitute |

|

Air blast |

Wind |

|

Alginate material |

Pudding |

|

Burr |

Brush |

|

High speed suction |

Vacuum cleaner |

|

Explorer |

Tooth feeler/counter |

|

Rubber dam |

Rubber raincoat |

|

Stainless steel crown |

Tooth hat |

|

Study models |

Statues of teeth |

|

X-ray film |

Tooth picture |

|

X-ray equipment |

Tooth camera |

|

Pit-fissure sealant |

Tooth (nail) polish |

Multisensory communication

The spoken word is not the only means of communication. Nonverbal communication, such as stroking the hand of a young child, communicates the feeling of warmth. A dental assistant’s smile conveys approval and acceptance. Similarly, these feelings can be transmitted through the eyes. Since communication is a reciprocal process, children who avoid eye contact are telling the dentist that they are not yet ready to cooperate fully. Hence, effective communication occurs through a multisensory approach.

Whenever communication occurs there is a transmitter, a medium, and a receiver. The dentist or dental health team is the transmitter, the office environment provides an array of media, and the child is the receiver. It is widely recognized that certain characteristics are typical of all three for good behavior management (Moss 1972).

The transmitter may be one or all of the members of the dental health team during a child’s dental visit. However, one fundamental rule must be recognized. Verbal transmission may come from only one direction at any given time . Children cannot divide their attention between two adults simultaneously or be distracted (Figure 6-3). If the dentist has entered into a discussion with the child, then the assistant must refrain from commenting. Typically, the error of two adults speaking to the child at one time occurs under stress. If a child resists an injection, the dentist may be trying to control her, and often a well-meaning dental assistant chimes in with words for the child. The communication then comes from two directions and the message becomes unclear.

The attitude of the transmitter is often conveyed through the voice. Voice intonation, tone, and modulation can express empathy and firmness. Often it is not what is said but rather how it is said that creates an impact. Young children do not always hear or understand words and sentences, thus repetition is almost always required. The transmission must be constant. A kind pattern can give a young child a feeling of security and promote behavior management.

Figure 6-3. The dentist explains the procedure to the child patient. Note that the child has ear phones in place. Effective communication can only come from one source at a time. Avoid ear phones and other distractors when communicating.

Since communication is multisensory, posture, movements, and position of the dental health team are extremely important nonverbal communication signs. Generally, movements should be slow and smooth, designed to convey a positive attitude and instill a feeling of security in the patient. Rough or gentle application of instruments also conveys an operator’s attitude. When speaking to a child, approximate the child’s level in the dental chair rather than tower above him.

The medium in the dentist-patient communication system is complex. While it obviously involves the projections of the office personnel, it also encompasses the dental office environment. Office design, pictorial displays, and background music all are media of communication. They convey messages, and should therefore be considered. When we deal with the school-age group, the latest music group may be preferable. Quiet background music, however, would be more likely to promote a settling effect for the very young child. The importance of the dental office environment is discussed in greater detail in Chapter Sixteen.

The visual channel must always be considered in multisensory communication. Sometimes those things which may seem natural to the dentist may be unsettling to a patient. A case in point is cited by one of the authors:

Case 6.5, Discussion: A friendly atmosphere sets the mood when a child patient and parent enter the reception room (see Chapter Sixteen). The welcoming smile of the receptionist, the décor of the room, and a homey atmosphere can all play an important role in establishing communication. The dentist treating children in general practice has to seriously consider how children react to the office environment.

Children in their roles as receivers also have characteristics that need to be recognized by the dental team for effective behavior management. Their focus of attention is narrow and indivisible. The messages being communicated must be continuous to hold their attention. If the dentist has to leave the operatory, someone else must transmit; otherwise the receiver builds up concerns. This oversight commonly occurs when the dentist leaves the operatory and the dental assistant focuses on chores (such as cleaning instruments) without communicating with the child. Left alone, fear can develop in these children.

Other senses of the receiver can be used to advantage. In school, children are encouraged to touch. Let them touch the rubber dam, prophylaxis cup, cotton roll and other non-harmful objects. Children should also be allowed to use their sense of smell and be made to feel comfortable. The positioning of the patient in the chair is important, and so is the positioning of light. Light shining in a child’s eyes can upset her potential as the receiver. Most children are good receivers. The message to be communicated is that the child can relax and need not be afraid.

Previous research has shown that the ability to assess non-verbal communication in children is closely related to the ability to observe. Using videotapes, Brockhouse and Pinkham (1980) studied the observational abilities of 141 participants and found that significant patterns evolved. One pattern was that pediatric dentists were more accurate in their abilities to predict behavior as compared to other experience levels. Dental assistants were significantly less accurate than others, including student groups. This finding was somewhat surprising, as many dental assistants had spent more chair time with children in the clinic than any other group. Another pattern revealed that freshman students had poorer predictive abilities than other dentist or student groups. They lacked clinical or didactic experience. The investigators concluded that experience appears to be the best means of developing the ability to assess non-verbal communication in children, but formal education is also important, perhaps because of the complexity of the communication process.

Confident communication

Speaking confidently to a child can lead to cooperative behavior. Many former dental students can relate to the following case.

Case 6.6, Discussion: To support the point that confidence is an important ingredient in communicating with the pediatric patient, a study of communication patterns was reported by Wurster et al. (1979). They examined communication patterns among sixteen randomly selected senior dental students and their child dental patients. Interactions were videotaped during regular treatment appointments. The data showed that the probability of a child’s behavior following a practitioner’s behavior was related. Patterns of behavior employed by clinicians will lead to a certain type of behavior on the part of the child. If the communication pattern is appropriate, the desired behavior likely will be achieved. In this same study, the operator’s confidence level was considered, and the results showed that less confident operators were responsible for 95% of coercive behavior, 86% of permissive behavior and 87% of uncooperative behavior.

Voice Control

Gaining a child’s attention is the ultimate aim of voice control. Without the attention of the child, there is no means of communication, and without communication, the child will never learn to be a good dental patient. The patient will miss the cues, lack motivation, respond improperly and miss the rewards of approbation by his parents and the dental staff. As well as being a method of communication, voice control is thought of as a management technique; therefore, it will be described more fully with the non-invasive techniques in this chapter.

Active Listening

Listening is important in the treatment of all children. Active listening (Wepman and Sonnenberg 1979) or reflective listening (Nash 2006) has the positive effect of reassuring children that what they are going through is a normal part of the human experience. Ways in which children’s feelings can be acknowledged include: (1) listening quietly, (2) acknowledging the feeling with a word such as “I see,” or (3) giving the feeling a name: “Are you really nervous about coming to see me today?” In dealing with older children, listening to the spoken words may be more important than it is with younger children when attention to non-verbal behavior is often more crucial. An example of good listening follows:

Dr. S. replied, “You don’t like the tooth raincoat?”

Mary said, “No. I can’t breathe when you put that in my mouth.”

Case 6.7, Discussion: By listening, Dr. S. learned what bothered M/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses