6

Dental Anxiety in Children and Adolescents

Definitions of Dental Fear and Anxiety and Dental Behaviour Management Problems

Fear represents a natural emotion based on a perception of a real threat. Especially young children frequently encounter new and unknown situations that are perceived as fearful. Anxiety on the other hand is associated with fear reactions towards a situation of anticipated but not realistic threat. It is an abnormal reaction and a disorder like fear may hinder the child in different situations.

In dentistry dental fear and dental anxiety are two different entities but are often used together and are even interchangeable. However, there is a distinction. Dental fear (DF) represents a reaction to a specific external threatening stimulus, a normal emotional reaction to threatening stimuli in the dental situation. Dental anxiety (DA) represents a state where the child is evoked and prepared for something to happen. It is not attached to an object but rather, it is a non-specific feeling of apprehension, associated with more abnormal conditions. Dental phobia (DP) represents a severe type of dental anxiety and is characterized by marked and persistent fear of clearly discernible situations/objects and is diagnosed according to clinical criteria (DSM-IV). DP interferes significantly with daily life and results in avoidance of necessary dental treatment or enduring treatment only with dread. In research, DF and DA have often been investigated without clear distinction and in this chapter, dental fear and anxiety (DFA) will therefore be used to describe psychological reactions that negatively interfere with children’s readiness to go through dental treatment.

Children are more prone to react overtly if they feel that something is wrong; if they are not treated in a way they like; or if they feel uncomfortable or perceive pain. For adults these kinds of behaviours are not accepted; something that the individual learns when growing up as part of the social norms. However, it should be kept in mind that despite not showing dislike or discomfort through behaviour, adult patients may well experience the same feelings of discomfort as the child, but just not show this openly. So, in contrast to dental care for adults, behavioural or cooperational problems are common in child dentistry. The term for this is dental behaviour management problems (DBMP), which is defined as uncooperative and disruptive behaviours resulting in delay of treatment or rendering treatment impossible. Thus, DBMP is recognized and defined by the dentist. It represents the dentist’s point of view and does not necessarily correspond to the child’s perspective or with the level of DFA perceived by the child.

Relationship between Dental Fear and Anxiety and Behaviour Management Problems

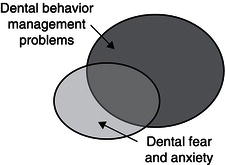

So is it then possible to distinguish between DFA and DBMP? There is no simple answer to this. No dentist is likely to miss a child presenting with DBMP. Most clinicians will recognize children with inadequate understanding, maturity or ability to cooperate and probably see this as DBMP. But it would be a misconception to just say it is DBMP. Looking at the situation from the child’s point of view, he or she at some point probably also experiences some level of fear. As a contrast to the child who is acting out, another child may instead be whispering to his or her mother, not making any eye contact with the dentist and distancing him- or herself from interaction. This would probably be recognized as DFA by many dentists. Children with DFA can be outgoing in their general behaviour, but are sometimes more passive and silent during treatment. It is therefore important not to take cooperative behaviours alone as a sign of the child feeling comfortable. If absence of disruptive patient behaviours is taken as a guarantee for feelings of ease with the situation, there is a risk of overlooking DFA. By not taking DFA into consideration and by not providing a treatment that is tailored for the individual patient, the dentist may even cause more anxiety problems. Apparently there is a distinction between DFA and DBMP, but there is also some overlap. The degree of overlap probably varies in different populations depending on age, maturity, cognitive properties, previous experiences of dental care, dental problems and so on. A Swedish study from the 1990s on 4-to-11-year-old children showed that 27 per cent of the children with DBMP also had DFA (Klingberg et al. 1995). Looking at the children with DFA, it was found that 61 per cent in this group also presented with DBMP (Figure 6.1). Consequently much of the research in this field does not distinguish between DFA and DBMP. For example, when looking at the literature one will find several studies where the study sample comprises patients referred to specialists because of disruptive behaviours in combination with dental caries and where the researchers evaluate the patients or follow-up treatment using DFA as an endpoint. Often the treatment concerns behaviour management techniques, i.e. methods enabling the dentist to carry out treatment and not aiming at reducing fear and anxiety. So for many dentists the child’s behaviour is the main issue even in research, while the child’s perspective may be something rather different, namely fear and anxiety.

Figure 6.1 The relationship between DFA and DBMP. Modified from Klingberg et al. 1995

Prevalence

There are several reports on the prevalence of DFA and DBMP in the literature, but it is often difficult to compare studies and there are two main reasons for this. The first concerns the differences in definition and measurement of DFA or DBMP and the second concerns the variation in study design and patient materials.

Both DBMP and DFA can be measured in several different ways. Starting with DBMP, most studies use observation of the child’s reaction or behaviour during dental treatment (behavioural ratings). The observations are usually made by a dentist or another person (present in the room or based on videotapes) and there are several well-known rating scales, for example the Frankl Scale (Frankl, Shiere and Fogels 1962). The assessments can be made at a detailed level for different parts of the treatment or at different time intervals, or as global assessments of the total treatment session. The most common way to measure DFA is by self-reports of anxiety by the child or by the accompanying parent (most often the mother) using psychometric scales. Parents are generally used as informants or as proxy for children under the age of 13. After that adolescents answer for themselves. It is known that the agreement between assessments of child DFA made by child or parent is far from perfect and therefore it is important not to combine data gathered from parents and children in research (Gustafsson et al. 2010). The most frequently used test for DFA is the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule – Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS) (Cuthbert and Melamed 1982). This test consists of 15 items scored on Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (not afraid at all) to 5 (very afraid) with a possible total score range from 15–75. The CFSS-DS was originally designed in a version where the child answered by using a fear thermometer, but today it is mainly used as a self-report in two versions – one using the child as informant and one where the parent is the informant. DFA is usually defined as scores equal to or exceeding 38 or 39 in the parental version of CFSS-DS (Klingberg and Broberg 2007). For children the cut-off levels vary more according to different studies (from 37 to 42) (Klingberg and Broberg 2007). When deciding on psychometric tests for DFA it is important to acknowledge that tests developed for adults are not generally applicable for children and adolescents, regardless of whether the child or an adult proxy is used. Further, as pointed out above, if a test like the CFSS-DS has both a child and a parental version this does not mean that the two versions are identical.

Study design is important in all studies, including prevalence studies. Many studies on DFA and DBMP comprise selected patient materials, often patients that have been referred to specialist clinics or patients at university clinics. These groups are not necessarily representative of the background population and thereby the sampling procedures introduce bias in many prevalence studies. It is likely to assume that patients seen at a dental clinic have greater dental treatment needs than those not seeing a dentist and, as some of these clinics provide dental care at lower cost, there is also potentially a bias concerning socioeconomic background. Further, young children in need of dental treatment may have an increased risk of pain experiences owing to cognitive development and difficulties with understanding and coping with discomfort, which again may result in disruptive behaviours and fear reactions. These are examples of biases that could result in an overestimation of the prevalence of DFA and DBMP in these groups compared with the ba/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses