Bleaching Techniques

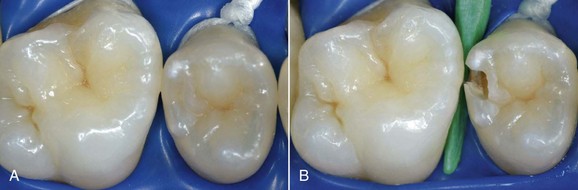

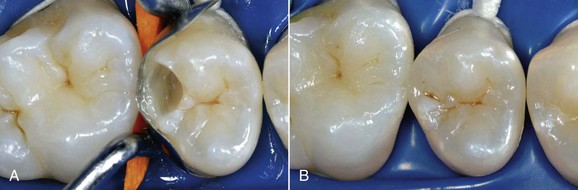

The dental world has responded very well to these demands and can provide good solutions to patients thanks to cutting-edge techniques and constantly evolving materials (Figure 6-1). Modern dentistry has increasingly leaned toward cosmetic, conservative and minimally invasive principles, possibly with direct access to the cavity, to achieve satisfactory results for both the patient and the specialist.

In this new clinical and social picture, bleaching procedures play an important role (Figures 6-2 to 6-7).

Example of Minimally Invasive Dentistry

The Enemies of Dental Esthetics

Pigmentation and Discoloration

Tooth pigmentation (extrinsic stain) occurs when coloring agents of various kinds (chromogenic bacteria, food dyes, beverages, or drugs) are fixed onto the acquired enamel pellicle (AEP) and diffuse through its surface layers (Figure 6-8). The best-known examples of substances containing exogenous pigments are coffee, tea, red wine, tobacco, licorice, chlorhexidine, and stannous fluoride. A high pH in the oral cavity favors the accumulation of pigments.

Figure 6-8 Examples of pigmentation. The patient on the right reported drinking 10 cups of tea a day.

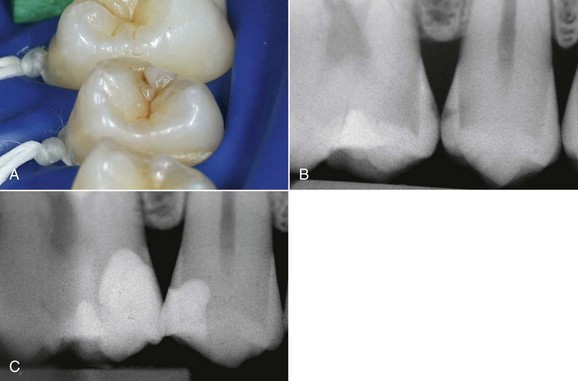

Tooth discoloration (intrinsic discoloration) instead occurs when the change in shade is caused by internal structural change of the optical properties of dental tissues or by accumulation of color-active agents within the dentin or enamel structure (Figures 6-9 and 6-10).

The following are the most frequent causes of discoloration:

• Aging: Teeth become gray or yellowish owing to deposition of tertiary dentine, tubular sclerosis, or ion exchange between dentin and enamel.

• Amelogenesis imperfecta (there are seven variants): Tooth color ranges from yellow to deep brown owing to disturbances during formation or maturation of the enamel.

• Dentinogenesis imperfecta: Tooth color ranges from red-brown to gray, and the cavum dentis is either obliterated or very reduced by the deposition of a very opalescent dentin.

• Fluorosis: The enamel is hypermineralized and exhibits structural alterations (increased number of pores); the color varies from white-gray (opaque fluorosis) to brown (simple fluorosis, Colorado brown stain) or can be extremely dark (pitting fluorosis).

• Hematologic diseases: Fetal erythroblastosis, thalassemia, sickle cell anemia, and various forms of porphyria may cause discoloration.

• Posttraumatic formation anomalies: Injuries of the deciduous dentition may cause opaque areas on permanent teeth.

• Discolorations caused by silver amalgam fillings, especially in the case of old restoration made with non–gamma-2 amalgam: The release of oxidation products sometimes produces significant color aberrations. For this type of discoloration the only possible treatment is mechanical removal of the hard tissues involved.

• Discoloration may be caused by specific endodontic cements.

• Systemic diseases: Hepatitis may result in discoloration.

• Tetracyclines: Yellow-brown (chlortetracycline) or grayish (demethylchlortetracycline) discolorations are caused by administration of the antibiotic before the eighth year of age. It is common knowledge that tetracyclines have a marked affinity for calcified tissues in formation, to which it binds in the form of orthophosphate. Intensity of discoloration seems to be more dose dependent than time dependent.

• Injuries and pulp necrosis: Although metabolic products resulting from hemorrhagic extravasation or tissue necrosis cause discoloration, the formation of dark ferrous sulfates from hemoglobin seems to play a major role.

Bleaching

Bleaching procedures can be classified as follows:

• Internal (or nonvital) bleaching. The active agent is placed within the pulp chamber by the dentist (in-office bleaching) and can also be left in place between sessions (“walking bleach”).

• External (or vital) bleaching. The active agent is placed in contact with the tooth surface. Despite its name, vital bleaching can obviously be performed only on endodontically treated teeth. Vital bleaching can be further divided into at-home bleaching (with self-application of the bleaching agent by the patient as instructed by the dentist) and in-office bleaching (in which the dental team performs the bleaching procedure at the dental chair). The agents used for at-home bleaching are obviously not as concentrated and are thus less powerful (“soft bleaching”) than those used in the office by the dentist (“power bleaching”). For the sake of completeness, I must also mention the microabrasion technique, which can be used in conjunction with bleaching procedures. Microabrasion removes the superficial layers of enamel by means of a strong (inorganic) acid and an abrasive powder and is followed by external bleaching. This procedure can be performed only in the office by a dentist.

At-Home Bleaching

Bleaching Tray

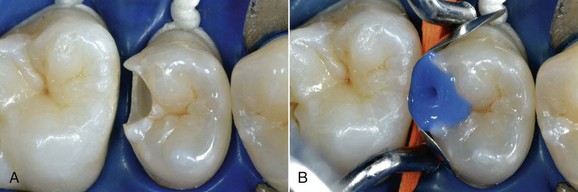

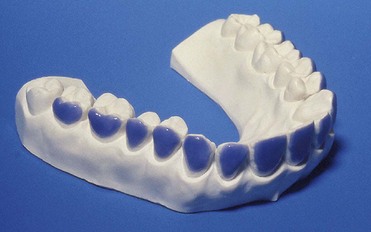

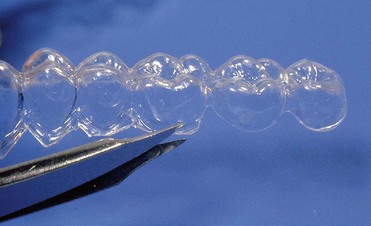

With at-home bleaching the most important aspects of the treatment are proper instruction, patient motivation, and a well-made bleaching tray. The fabrication of the tray is very important, and the dentist should detail to the dental technician all the procedures needed for a well-fitted tray (Figures 6-11 to 6-17).

Two types of bleaching tray are available on the market.

Figure 6-16 Finished tray on the model.

Vital Bleaching: Indications and Contraindications

• Simple pigmentation: One session of oral hygiene, or possibly enamel microabrasion, can solve the problem

• Poorly motivated or uncooperative patients

• Young teeth with large pulp chambers

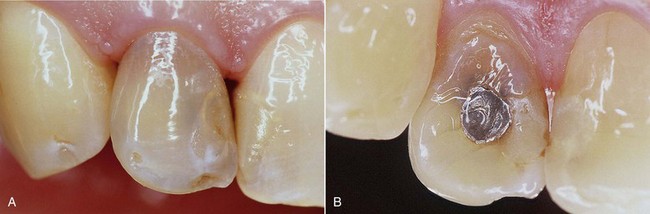

• Enamel defects (e.g., macroporosity) predisposed to very rapid relapse owing to penetration of exogenous pigments (Figure 6-18)

Figure 6-18 Structural defects occurred during tooth formation. At-home bleaching is absolutely contraindicated.

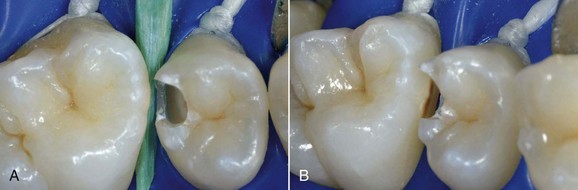

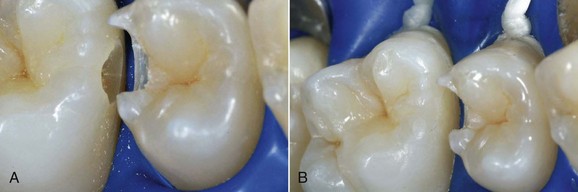

• Teeth that have been extensively restored have faulty restorations or, worst of all, have caries (Figures 6-19 and 6-20)

Tetracycline Discoloration

Tetracycline discoloration is classified into three groups according to severity.

In first-degree discoloration there is a decrease in tooth shade value, and the tooth has a darker color at the cervical region. The tooth loses brightness (Figure 6-21). First-degree tetracycline discoloration can be treated with a good degree of predictability. In second-degree discoloration there is a further loss of value and the chroma is darker but fairly uniform. In this case as well, bleaching yields appreciable results (Figure 6-22).

Figure 6-21 First-degree tetracycline discoloration.

Figure 6-22 Second-degree tetracycline discoloration.

Third-degree discoloration, however, exhibits horizontal banding of different contrasting colors. With this type of discoloration a conservative approach is no longer feasible. More aggressive treatment, such as ceramic veneers or full crowns, is required to achieve esthetic improvement (Figure 6-23).

Figure 6-23 Third-degree tetracycline discoloration.

Side Effects

Microfilled hybrid composites, which are now the most widely used, do not seem to encounter significant changes. Peroxides, however, seem to accelerate the aging process of composite resins substantially. Therefore it is always best (not only from the standpoint of color consistency) to perform the bleaching procedure before composite restorations. The cytotoxicity of carbamide peroxide is not an issue and is similar to that of many other materials for dental use, such as eugenol and oxyphosphate temporary cements. Animal studies did not reveal any mutagenic or teratogenic effect for 10% carbamide peroxide. The lethal dose of a 10% solution for a subject weighing 75 kg (165 lb) is 6.5 to 8 L (1.5 to 1.8 gal) (Figure 6-24).

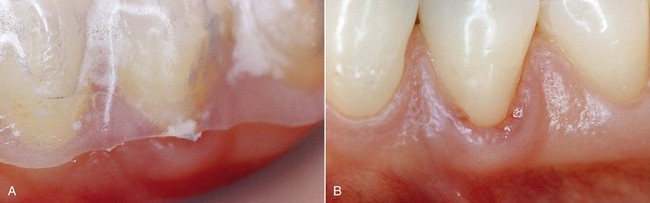

The presence of finishing imperfections on the tray may cause minor pressure ulcers, which heal very rapidly once the compression area on the tray has been ground down (Figure 6-25).

Available Products

There are many products on the market for exclusive dental use.

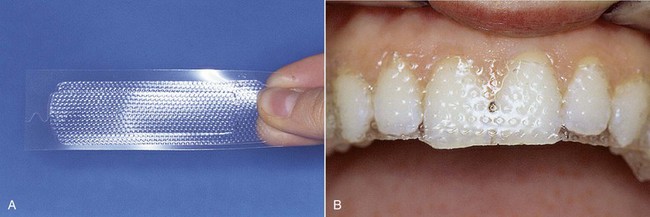

In recent years, over-the-counter bleaching products have been sold at supermarkets and pharmacies (Figures 6-26 and 6-27). Numerous patients ask if these systems are effective. Treatment performed by a dentist will naturally achieve far better and more predictable results than do-it-yourself procedures.

Figure 6-26 Whitening strips.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses