Endodontics

Learning Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to achieve the following objectives:

• Pronounce, define, and spell the Key Terms.

• Describe the diagnostic testing performed for endodontic diagnosis.

• List the conclusions of the subjective and objective tests used in endodontic diagnosis.

• Describe diagnostic conclusions for endodontic therapy.

• List the types of endodontic procedures.

• Discuss the medicaments and dental materials used in endodontics.

• Provide an overview of root canal therapy.

• Describe surgical endodontics and how it affects treatment.

Performance Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to achieve competency standards in the following skills:

Electronic Resources

![]() Additional information related to content in Chapter 54 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

Additional information related to content in Chapter 54 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

• Interactive Dental Office Patient Case Studies: Antonio DeAngelis and Cindy Valladares

• Procedure Sequencing Exercises

• WebLinks

Key Terms

Abscess (AB-ses) A localized accumulation of pus in a cavity formed by tissue disintegration.

Acute (uh-KYOOT) Pertaining to a traumatic, pathologic, or physiologic occurrence or process that has a short and relatively severe course.

Apical curettage (AP-i-kul kyoor-uh-TAHZH) Surgical removal of infectious material surrounding the apex of a root.

Apicoectomy (ap-i-ko-EK-tuh-mee) Surgical removal of the apical portion of the tooth through a surgical opening made in the overlying bone and gingival tissues.

Chronic Pertaining to disease symptoms that persist over a long time.

Control tooth Healthy tooth used as a standard to compare questionable teeth of similar size and structure during pulp vitality testing.

Debridement (day-breed-MAW, di-BREED-munt) To remove or clean out the pulpal canal.

Direct pulp cap Application of dental material with an exposed or nearly exposed dental pulp.

Gutta-percha (guh-tuh-PUR-chuh) Plastic type of filling material used in endodontics.

Hemisection (hem-ee-SEK-shun) Surgical separation of a multirooted tooth through the furcation area.

Indirect pulp cap Placement of a medicament over a partially exposed pulp.

Irreversible pulpitis (pul-PYE-tis) Infectious condition in which the pulp is incapable of healing, which would then require root canal therapy.

Nonvital Not living, as in oral tissue and tooth structure.

Obturation (ob-tuh-RAY-shun) Process of filling a root canal.

Palpation (pal-PAY-shun) Technique of examining the soft tissue with the examiner’s hands or fingertips.

Percussion (pur-KUH-shun) Examination technique that involves tapping on the incisal or occlusal surface of a tooth to assess vitality.

Perforation (pur-fuh-RAY-shun) Making a hole, as in breaking through and extending beyond the apex of the root.

Periodontal abscess An inflammatory reaction to bacteria trapped in the periodontal sulcus.

Periradicular (per-ee-ruh-DIK-yoo-lur) Referring to the area of nerves, blood vessels, and tissues that surrounds the root of a tooth.

Periradicular abscess An inflammatory reaction to pulpal infection.

Periradicular cyst A cyst that develops at or near the root of a necrotic tooth.

Pulpectomy (pul-PEK-tuh-mee) Complete removal of vital pulp from a tooth.

Pulpitis (pul-PYE-tis) Inflammation of the dental pulp.

Pulpotomy (pul-POT-uh-mee) Removal of the coronal portion of a vital pulp from a tooth.

Retrograde restoration (RET-roe-grayd res-tuh-RAY-shun) Small restoration placed at the apex of a root.

Reversible pulpitis Form of pulpal inflammation in which the pulp may be salvageable.

Root amputation (am-pyoo-TAY-shun) Removal of one or more roots without removal of the crown of the tooth.

Root canal therapy Removal of the dental pulp and filling of the canal with material.

Endodontics was recognized as a specialty in dentistry in 1963 by the American Dental Association. This unique specialty manages the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the dental pulp and the periradicular tissues that surround the root of the tooth. Endodontic treatment, often referred to as root canal therapy, provides an effective means of saving a tooth that might otherwise have to be extracted.

The general dentist is skilled and qualified to perform endodontic treatment; however, dentists will refer patients in need of this treatment to an endodontist, a dentist who specializes in this area. An endodontist is a general dentist who has continued training for a minimum of 3 years in the clinical skill and research of pulp therapy.

Causes of Pulpal Damage

The two main sources of pulpal nerve damage are physical irritation and trauma. Physical irritation is most often caused by extensive decay that has moved into the pulp-carrying bacteria. When bacteria reach the nerves and blood vessels, infection will result in an abscess, which is a localized area of pus (Fig. 54-1).

Trauma, such as a blow to a tooth or the jaw, can cause damage to surrounding tissues. Over time, this damage will affect the nerve tissue and blood vessels of the pulp (Fig. 54-2).

Symptoms of Pulpal Damage

Sensitivity, discomfort, and pain may be symptoms of pulpal nerve damage. Even though patients experience symptoms differently, the most common signs and symptoms of pulpal damage include the following:

Endodontic Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a tooth that requires endodontic treatment is based on an examination that consists of subjective and objective components.

The subjective examination includes an evaluation of symptoms or problems described by the patient, which include the following:

The objective examination is conducted by the endodontist, who evaluates the status of the tooth and surrounding tissues with regard to the following:

Several techniques are used to test pulp vitality in determining whether endodontic therapy is required, or if the pulp is vital and is able to repair itself. When a questionable tooth is tested for vitality, a control tooth is selected to use for comparison. A healthy tooth, usually of the same type, in the opposite quadrant is selected as a control tooth. For example, if the maxillary right first premolar is the suspect tooth, the control tooth would be the maxillary left first premolar. The use of a control tooth shows that the stimulus is capable of achieving a response.

Percussion and Palpation

Percussion and palpation tests are used to determine whether the inflammatory process has extended into the periapical tissues. A positive response to these tests indicates that inflammation is present in the periodontal ligament, and that endodontic treatment is most likely required.

The dentist performs the percussion test by tapping on the incisal or occlusal surface of the tooth in question with the end of the mouth mirror handle, which is held parallel to the long axis of the tooth (Fig. 54-3).

The dentist performs the palpation test by applying firm pressure to the mucosa above the apex of the root (Fig. 54-4) and noting any sensitivity or swelling.

Thermal Sensitivity

Tests using extreme temperature can provide another method of determining the status of the pulp. A thermal stimulus is never used on a metallic restoration or on gingival tissue. Application of extreme temperatures in this situation will result in an abnormal response and possible damage to the tissues.

In the cold test, the dentist uses ice, dry ice, or carbon dioxide to evaluate the response of a tooth to cold. First, the control tooth and the suspect tooth are isolated and dried. Next, the source of cold is applied first to the cervical area of the control tooth, then to the cervical area of the suspect tooth (Fig. 54-5).

A necrotic pulp will not respond to cold. Irreversible pulpitis is suspected when the cold relieves the pain; however, cold in teeth with irreversible pulpitis also can initiate severe, lingering pain.

The heat test is generally the least useful of the vitality tests because a painful response to heat could indicate either reversible pulpitis or irreversible pulpitis. A necrotic pulp will not respond to heat. A small (pea-sized) piece of gutta-percha is heated in a flame and then is applied to the facial surface of the tooth. Another method is to heat the end of an instrument and place it on the tooth. Petroleum jelly should be applied to the tooth surface before testing to prevent the material from sticking to the tooth surface.

Electric Pulp Testing

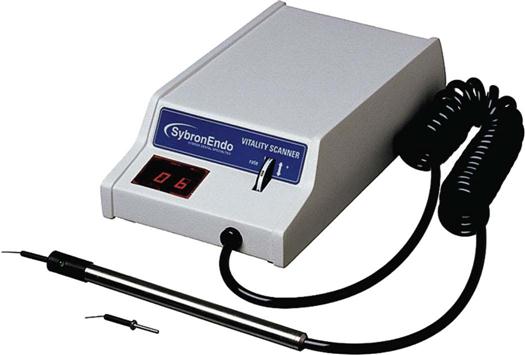

Electric pulp testing is used in endodontic diagnosis to determine whether a pulp is vital or nonvital. Similar to other testing devices discussed, the pulp tester can produce a false-positive or a false-negative response (test results that show a positive or a negative response incorrectly). Therefore, test results must be supported by other diagnostic findings.

Electric pulp testers deliver a small electrical stimulus to the pulp (Fig. 54-6). Factors that influence the reliability of the pulp tester include the following:

• Teeth with extensive restorations can vary in response.

• Teeth with more than one canal can have one vital canal and other nonvital canals.

• A failing pulp can produce a variety of responses.

• Control teeth may not respond as anticipated.

• Moisture on the tooth during testing may produce an inaccurate reading.

See Procedure 54-1.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses