Chapter 5

Prevention of Oral Disease I: Periodontal Disease

Aim

This aim of this chapter is to guide the team through the promotion of effective oral hygiene and smoking cessation advice for the individual patient.

Outcome

The team members should have an understanding of the suggested methods of delivery of oral health messages to prevent diseases of the supporting tissues and the oral mucosa.

Oral Hygiene Instruction

Successful general dental practices have a co-ordinated team approach to the prevention of periodontal diseases. To achieve success consideration must be given to effective patient education and consistent long-term patient motivation.

Education

The more often oral health messages are transmitted to the patient utilising different forms of media, the more likely a positive response. First, the patient must accept that the advice applies to them as an individual and then they must commit themselves to achieving positive outcomes. From the outset the patient must recognise that they have a disease of the supporting tissues of their teeth, induced by microbial plaque and modified by their host response, that many others do not have. The education process commences with the dentist at diagnosis and is reinforced by the hygienist. It is strengthened by the nursing and reception staff, especially if they are responsible for advice on and selling of oral hygiene products. Human beings forget health messages, or do not identify with them. Reinforcement is therefore required at every visit and, in particular, at a recall appointment.

To be effective the patient requires consistent advice from the staff. In order to achieve this, practice policies should be discussed at team meetings. This may include a policy on which oral health products to offer for sale, or coordination of smoking cessation advice.

Motivation

According to the “expectancy value” theory of motivation, if a patient is to engage in an activity then they must value the outcome and expect success in achieving it. The impact of value and expectancy is multiplied. It is not simply additive; both factors need to be present. If either value or expectancy is absent then the motivated activity will not occur. The expectancy value theory is particularly relevant in the early stages of learning, i.e. when a patient first learns of the diagnosis of periodontal disease. The entire team has a key role to play in the value of addressing lifestyle changes and encouraging positive outcomes when these changes are acted upon.

Products in Practice

It is advisable to appoint a co-ordinator who regularly updates the products and consults with clinicians regarding specific requirements. In practices with an input from visiting specialists, the products may range from maintenance of implants to fixed orthodontic appliances. Chemical plaque control and dentifrices should also be available with the emphasis being on proven efficacy in independent randomised clinical trials. Representatives can be very persuasive, but must be able to provide evidence if requested to substantiate their claims. Recommended oral hygiene products should be:

-

individualised

-

readily available

-

effective

-

good value for money

-

easy to use.

Individual Instruction

Oral hygiene aids must be individualised. It may be stating the obvious but each patient’s mouth is unique – in shape, size, dentition and musculature. Add to this the varying degrees of true and false pocketing, complex restorations, crowding of teeth, a hypersensitive gag reflex, dentures, and very different host responses, and plaque control becomes extremely complex!

Instructions to the patient, who may not be manually dextrous, or who has conflicting priorities in life, require effort, time and patience on the part of the clinician. They involve reinforcement over several visits, beginning with basic tooth brushing technique and progressing onto interdental cleaning once the mouth “map” has been imprinted in the patient’s thinking.

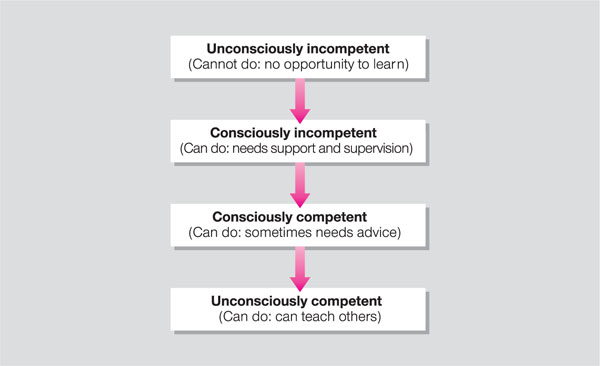

The process includes breaking the cycle of unconscious actions carried out ineffectively. For some patients these processes may have been in place for over 50 years. These have to be replaced with new techniques, which at first will be consciously undertaken but later will become unconscious activities again. The “ladder of competence” paradigm used by teachers is relevant here (Fig 5-1).

Fig 5-1 Ladder of competence.

Patients with periodontal disease have by definition an inappropriate host response to the microbial biofilm. In order to maintain health, they have to be highly efficient at plaque control. Furthermore, this exercise has no definitive time frame; it requires daily commitment for life!

Demonstration of plaque control has therefore to be on a one-to-one basis. It has to be given by a clinician who is legally permitted to place their hands inside a patient’s mouth and who has an understanding of the patient’s oral disease status, medical status and plaque retention factors. It does not necessarily have to be taught in the dental chair, but this is preferable for several reasons.

The chair is manoeuvrable and has a head rest – this allows access to demonstrate difficult sites. There is a light source for good illumination of posterior sites. There will be a mouth mirror and a blunt probe available to aid education. There is a bowl for expectoration. Cross-infection control must be maintained.

Adults tend to be embarrassed by a demonstration on oral hygiene and, in particular, by having to practise it in front of others. To respect privacy, if a preventive unit is to be used it is advisable only to have one adult at a time. Children, on the other hand, have fewer oral complications, particularly the younger age groups with only the primary dentition to maintain. They usually require toothbrush instruction only and enjoy the company of other children. They may be instructed in a preventive dental unit environment with a trained oral health educator. For older children requiring interdental cleaning instructions and maintenance of fixed appliances, the more personal approach for adults should be followed.

How to give the advice

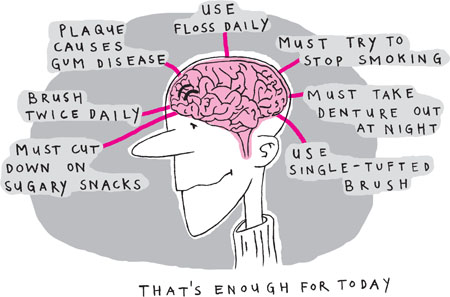

Broadly speaking, people can retain about seven pieces of information at any one time (Fig 5-2). If some of this information is visual and some linguistic, the total increases.

Fig 5-2 “My brain is about to burst.”

If the patient hears the health message only, 20% of the information will be retained. If they see the message in a visual form, 50% of the information is retained. If the instructor encourages the patient to speak back the message, then 70% of the information is retained. By far the most effective retention, however, is by the patient demonstrating the skill back to the instructor.

Hear it and I forget it

Speak it and I remember

Do it and I know. (ancient Chinese proverb)

The method for delivery of the message must also be considered. The aim is for the patient to identify the instructions with his or her own mouth (Fig 5-3). For this reason a traditional toothbrush demonstration on a plastic model is to be avoided. The patient sees a demonstration of a plastic model (with perfect teeth!) being brushed – not their own mouth. If the clinician orientates the model so that the lower arch is at the same orientation as the patient’s lower arch then the patient has to crane their head to see it. If the clinician sits facing the patient and gains eye contact, the model is in reverse. Demonstration of the brushing of the maxillary teeth is especially difficult, as patients are not familiar with mirror images of the mouth.

Fig 5-3 Identification of the individual problems.

The patient must be advised to bring his or her own toothbrush to the session (Fig 5-4). This is especially important if the patient uses a power brush, but they must be reminded to charge it! Alternatively, the practice may provide manual brushes of a suitable size for personal demonstration. A reminder on the reverse of the appointment card to bring in all oral cleaning devices will help. An option is to provide an individual starter pack to all new patients. It is a goodwill gesture, which will encourage the use of customised products. The patient is then able to try brushes or interdental tape with the clinician present, who can advise accordingly. Unfortunately, many of the hand held interdental brushes are not available for sale in retail outlets and have to be ordered by mail order. This involves effort on the part of the patient and a possible time lag between order and supply, which can lead to a relapse in plaque control. If the practice is seriously promoting prevention of periodontal disease, then the brushes need to be available for patients to purchase on site. The various manufacturers do not standardise the colour of the handles according to the brush or wire diameter and this adds confusion to the choice. Communication is aided by recording in the records the precise interdental cleaning aid used, i.e. the brand name and the handle colour (Fig 5-5).

Fig 5-4 “I was thinking of something a little smaller!”

Fig 5-5 A range of short-handled colour-coded interdental brushes.

Patients will only continue to buy products if they perceive them to be good value for money i.e. effective for the purpose of plaque removal and lasting for a “reasonable” period of time. Interdental brushes buckle and bend if they are too large for the interdental space, at which point the patient may become despondent and discontinue use. At every visit the brushes need to be checked for a snug fit (Fig 5-6).

Fig 5-6 The interdental brushes must fit snugly between the teeth.

As gingival recession occurs the interdental spaces become larger and the brushes need to be correspondingly larger to remove the plaque. Furcation sites will also become visible and cleansable with the correct brush, depending on the degree of furcation involvement.

Once manual dexterity has improved, the patient can be taught to ap/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses