Chapter 5

Periodontology

Contents

Principal sources and further reading J. Lindhe 2008 Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry (5e), Munksgaard. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, Munksgaard.

Oral microbiology

The mouth is colonized by microorganisms a few hours after birth, mainly by aerobic and facultative anaerobic organisms. The eruption of teeth allows the development of a complex ecosystem of microorganisms. Around 700 different species can colonize the mouth and the healthy mouth depends on maintaining an environment in which these organisms coexist without damaging oral structures.

Microorganisms worth noting

Streptococcus mutans

group Several species are recognized within this group, including S. mutans and S. sobrinus. Facultative anaerobe. Synthe-sizes dextrans. Colony density rises to >50% in presence of high dietary sucrose. Able to produce acid from most sugars. Most important organisms in the aetiology of caries.

Streptococcus oralis

group includes S. sanguis, S. mitis, and S. oralis. Account for up to 50% of streptococci in plaque. Heavily implicated in 50% of cases of infective endocarditis.

Streptococcus salivarius

group accounts for about half the streptococci in saliva. Inconsistent producer of dextran.

S. intermedius, S. angiosus, S. constellatus

(formerly S. milleri group) Common isolates from abscesses in the mouth and at distant sites.

Lactobacillus

Secondary colonizer in caries. Very acidogenic. Often found in dentine caries.

Porphyromonas gingivalis

Obligate anaerobe associated with chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans

Microaerophilic, capnophilic, Gram −ve rod. Particular pathogen in aggressive periodontitis.

Tannerella Forsythia

Prevotella intermedia

Found in chronic periodontitis, localized aggressive periodontitis, (juvenile periodontitis), necrotizing periodontal disease, and areas of severe gingival inflammation without attachment loss.

Prevotella nigrescens

New, possibly more virulent.

Fusobacterium

Obligate anaerobes. Originally thought to be principal pathogens in necrotizing periodontal disease. Remain a significant periodontal pathogen.

Spirochaetes

Obligate anaerobes implicated in periodontal disease; present in most adult mouths. Borrelia, Treponema, and Leptospira belong to this family.

Borrelia vincenti (refringens)

Large oral spirochaete; probably only a co-pathogen.

Actinomyces israelii

Filamentous organism; major cause of actinomycosis. A persistent rare infection which occurs predominantly in the mouth and jaws and the female reproductive tract. Implicated in root caries.

Candida albicans

Yeast-like fungus, famous as an opportunistic oral pathogen; probably carried as a commensal by most people.

Plaque

Dental plaque, which is a biofilm, is a firmly adherent mass of bacteria in a muco-polysaccharide matrix. It cannot be rinsed off but can be removed by brushing. It is the root of most dental evils.

Attachment

Although it is possible for plaque to collect on irregular surfaces in the mouth, to colonize smooth tooth surfaces it needs the presence of acquired pellicle. This is a thin layer of salivary glycoproteins, formed on the tooth surface within minutes of polishing. The pellicle has anion-regulating function between tooth and saliva and contains immuno-globulins, complement, and lysozyme.

Development

Up to 106 viable bacteria per mm2 of tooth surface can be recovered 1h after cleaning;1 these are selectively adsorbed streptococci. Bacteria recolonize the tooth surface in a predictable sequence. Streptococcus mutans synthesizes extracellular polysaccharides (glucan and fructan) specifically from sucrose and promotes its early colonization in this way. Cocci predominate in plaque for the first 2 days, following which rods and filamentous organisms become involved. This is associated with ↑ numbers of leucocytes at the gingival margin. Between 6 and 10 days, if no cleaning has taken place, vibrios and spirochaetes appear in plaque and this is associated with clinical gingivitis. It is generally felt that the move towards a more Gram −ve anaerobe-dense plaque is associated with the progression of gingivitis and periodontal disease.

Plaque in caries

(p. 24) As several oral streptococci, most notably mutans streptococci, secrete acids and the matrix component of plaque, there is a clear relationship between the two. However, various other factors complicate the picture, including saliva, other microorganisms, and the structure of the tooth surface.

Plaque in periodontal disease

There is a direct correlation between the amount of plaque at the cervical margin of teeth and the severity of gingivitis,2 and experimental gingivitis can be produced and abolished bysuspending and reintroducing oral hygiene.3 It is commonly accepted that plaque accumulation causes gingivitis, the major variable being host susceptibility. While there are numerous interacting components which determine the progression of chronic gingivitis to periodontitis, particularly host susceptibility, the presence of plaque, particularly ‘old’ plaque with its high anaerobe content, is widely held to be crucial, and most Rx is based on the meticulous, regular removal of plaque.

Calculus

Calculus (tartar) is a calcified deposit found on teeth (and other solid oral structures) and is formed by mineralization of plaque deposits. It can be subdivided into:

Supragingival calculus,

most often found opposite the openings of thesalivary ducts, i.e.  opposite the parotid (Stensen’s) duct and on the lingual surface of the lower anterior teeth opposite the submandibular/ sublingual (Wharton’s) duct. It is usually yellow, but can become stained a variety of colours.

opposite the parotid (Stensen’s) duct and on the lingual surface of the lower anterior teeth opposite the submandibular/ sublingual (Wharton’s) duct. It is usually yellow, but can become stained a variety of colours.

Subgingival calculus

is found, not surprisingly, underneath the gingival margin and is firmly attached to tooth roots. It tends to be brown or black, is extremely tenacious, and is most often found on interproximal and lingual surfaces. It may be identified visually, by touch using a WHO 621 probe, or on radiographs. With gingival recession it can become supragingival.

Composition

Consists of up to 80% inorganic salts, mostly crystalline, the major components being calcium and phosphorus. The microscopic structure is basically that of a randomly orientated crystal formation.

Formation

is always preceded by plaque deposition, the plaque servingas an organic matrix for subsequent mineralization. Initially, the matrixbetween organisms becomes calcified with, eventually, the organisms themselves becoming mineralized. Subgingival calculus usually takes many months to form, whereas friable supragingival calculus may form within 2 weeks.

Pathological effect

Calculus (particularly, subgingival calculus), is associated with periodontal disease. This may be because it is invariably covered by a layer of plaque. Its principal detrimental effect is probably that it acts as a retention site for plaque and bacterial toxins. The presence of calculus makes it difficult to implement adequate oral hygiene.

Aetiology of periodontal disease

Plaque is the principal aetiological factor in virtually all forms of periodontal disease. Periodontal damage is almost certainly the direct consequence of colonization of the gingival sulcus by organisms within dental plaque. However, the progression from gingivitis to periodontitis is far more complex than this statement suggests, as it involves host defence, the oral environment, the pathogenicity of organisms, and plaque maturity. It is probably easiest to regard periodontal disease as a complex multifactorial infection complicated by the inflammatory response of the host. Various elements of this process are worthy of special note:

Microbiology

The changing microbiology of dental plaque has already been referred to (p. 176). The inflammatory response of gingiva to the presence of initial young plaque creates a minute gingival pocket which serves as an ideal environment for further bacterial colonization, providing all the nutrients required for the growth of numerous fastidious organisms. In addition, there is an extremely low oxygen level within gingival pockets, which favours the development of obligate anaerobes, several of which are closely associated with the progression of periodontal disease. High levels of carbon dioxide favour the establishment of the capnophilic organisms, some of which are associated with localized aggressive periodontitis (LAP).

Briefly, clinically healthy gingivae are associated with a high proportion of Gram +ve rods and cocci which are facultatively anaerobic or aerobic. Gingivitis is associated with an ↑ number of facultative anaerobes, strict anaerobes, and an increasing number of Gram −ve rods. Established periodontitis is associated with a majority presence of anaerobic Gram −ve rods.

The 1996 World Workshop in Periodontics identified 3 species as causative factors for periodontitis. These are Aggregibacter actinomycetemcomitans Aa (previously called Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans), Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythia. However these are not the only causative pathogens and there are other putative pathogens for which there is evidence. These are: Prevotella intermedia, P melaninogenica, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Peptostreptococcus micros, Eubacterium species, Eikenella corrodens, Prevotella nigrescens, Treponema denticola and Campylobacter rectus. There is a strong association between Aa and localized aggressive periodontitis.

Some studies have suggested that specific viruses may be responsible for the aetiology and progression of periodontal lesions.1

Immunopathology

The inflammatory response to the presence of dental plaque is detectable both clinically and histologically, and is certainly responsible for at least some of the periodontal destruction which occurs. Both inflammatory and immunologically mediated pathways can contribute to periodontal damage. Antigenic substances released by plaque organisms elicit both cell-mediated and humoral responses which, while designed to be protective, also cause local tissue damage, usually by complement activation (Bystander Damage). Non-immune mediated damage is caused by one or all of the major endogenous mediators of inflammation: vasoactive amines (histamine), plasma proteases (complement), prostaglandins and leukotrienes, lysosomal acid hydrolases, proteases, free radicals, and cytokines.

Host response

Local and systemic modifying factors influence progress of the disease.

Systemic factors

include smoking, immune status, stress, endocrine function (e.g. diabetes), drugs, genetic factors, age, and nutrition.

Local factors

are tooth position and morphology, calculus, overhangs and appliances, occlusal trauma, and mucogingival state.

Periodontal disease and risk for systemic disease

There is a growing body of evidence suggesting an association between periodontal disease and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, pregnancy complications, diabetes, respiratory disease, kidney disease and certain cancers. No conclusions can yet be drawn as to whether these are causal associations, however it highlights the importance of oral health as part of a generally healthy lifestyle.1

Pathogenesis of gingivitis and periodontitis

Initial lesion:

Develops as plaque accumulates around the gingival margins.

At 24h there is vasodilation in the adjacent gingival tissues.

2–4 days: increased intercellular gaps therefore gingival crevicular fluid flow flushes noxious substances away and releases antibodies, complement and protease inhibitors. Polymorphs appear.

Early lesion:

May persist for a long time. After several days there are increased numbers of vascular units therefore clinically there is erythema. Lymphocytes and polymorphs predominate. Fibroblasts degenerate and collagen fibres break down. The basal cells of the junctional epithelium and sulcular epithelium proliferate to form rete pegs in the adjacent connective tissue. Subgingival biofilm develops as junctional epithelium loses contact with enamel.

Established lesion:

Gingival crevicular fluid flow increases. There are increased numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the connective tissue and junctional epithelium. The junctional epithelium converts to pocket epithelium. The established lesion may remain stable with no progression for months or years or may convert to a destructive advanced lesion.

Advanced lesion:

As the pocket deepens the biofilm continues to develop apically. Inflammatory cell infiltrate extends further apically into the connective tissues. Plasma cells dominate There is loss of connective tissue attachment and alveolar bone which represents the onset of periodontitis.

The disease is initiated and maintained by substances produced by the biofilm. Some (such as proteases) cause direct injury to host cells, some cause tissue injury by activation of host inflammatory and immune responses.

Epidemiology of periodontal disease

Epidemiology is the study of the presence, severity and effect of disease on a population. This helps identify aetiological and risk factors and effectiveness of preventive and therapeutic measures at a population level. Various scoring systems for measuring periodontal disease in a population have been developed. The value of these indices in the screening and management of individual patients soon became apparent. The following two indices fulfil both these criteria and are simple and easy to perform:

Debris or Oral Hygiene Index

This can be modified for personal use by using disclosing agents.1

0 No debris or stain.

1 Soft debris covering not more than ⅓ of the tooth surface.

2 Soft debris covering more than ⅓ but less than ⅔.

3 Soft debris covering over ⅔ of tooth surface.

Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE)

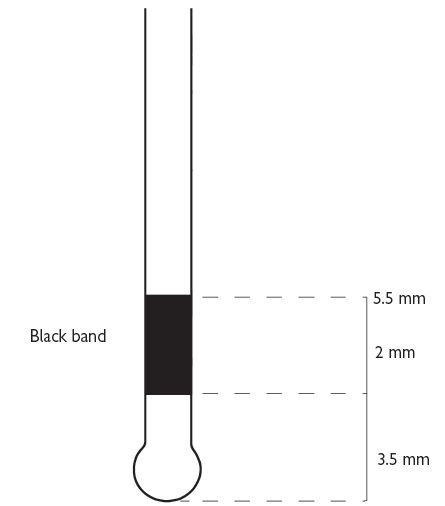

Also known as Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN).2 This technique is used to screen for those patients requiring more detailed periodontal examination. It examines every tooth in the mouth (except third molars), thus taking into account the site-specific nature of periodontal disease. A World Health Organization (WHO) periodontal probe (ball-ended with a coloured band 3.5–5.5mm from the tip) should be used (Figure 5.1). The mouth is divided into sextants, i.e. two buccal and one labial segment per arch. Six sites on each tooth are explored and the highest score per sextant recorded, usually in a simple six-box chart.

Fig. 5.1

0 = No disease,

1 = Gingival bleeding but no pockets, no calculus, no overhanging restoration. Rx: OHI.

2 = No pockets >3mm, but plaque retention factors present, e.g. overhang. Rx: OHI, scaling, and correction of any iatrogenic problems.

3 = Deepest pocket 4 or 5mm. Rx: OHI, scaling, and root planing.

4 = One or more tooth in sextant has a pocket >6mm. Rx: scaling and root planing, &/or flap as required.

* = Furcation or total loss of attachment of 7mm or more. Rx: full periodontal examination of the sextant regardless of CPITN score.

Individuals identified as having areas of advanced periodontal disease will require a full probing depth chart, together with recordings of mobility, recession and furcation involvement, and radiological examination. BPE cannot be used for close monitoring of the progress of Rx.

Other techniques for assessing the levels of periodontal disease include:

Marginal bleeding index (MBI)

Score 1 or 0 depending on whether or not bleeding occurs after a probe is gently run around the gingival sulcus. A percentage score is obtained by dividing by the number of teeth and multiplying the result by 100.

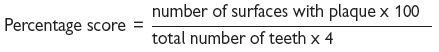

Plaque index (PI)

This is based on the presence or absence of plaque on the mesial, distal, lingual, and buccal surfaces revealed by disclosing.

Both the MBI and Pl can be expressed as bleeding or plaque-free scores in this way obtaining a high score is a good thing, which may be both easier for the patient to understand and a more positive motivational approach.

Although periodontal diseases are very common, severe forms affect no more than about 10–15% of the population. Overall, periodontitis accounts for between 30 and 35% of all tooth extractions; caries and its consequences account for up to 50%.1

The direct association between the presence of tooth surface plaque and periodontal damage has been confirmed, but the rate of destruction has been shown to vary, not only between individuals but also between different sites in the same mouth, and at different times in the same individual.

WHO probe for use in BPE/CPITN (Figure 5.1).

If black band disappears on probing pocket, perform full periodontal examination in that sextant.

Classification and diagnosis

Classification of periodontal disease

The currently used classification of periodontal diseases was introduced by the 1999 International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions.

| I | Gingival diseases (non-plaque induced and plaque induced) |

| II | Chronic periodontitis. |

| III | Aggressive periodontitis. |

| IV | Periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic disease. |

| V | Necrotizing periodontal diseases. |

| VI | Abscesses of the periodontium. |

| VII | Periodontitis associated with endodontic lesions. |

| VIII | Development or acquired deformities and conditions. |

Plaque associated periodontal disease are infections caused by microorganisms that colonize the tooth surface at or below the gingival margin.

The primary cause is bacterial plaque but associated risk factors are: specific bacteria, cigarette smoking and diabetes mellitus. There is a two-way association between periodontitis and diabetes with more severe periodontal destruction associated with diabetes but poorer control of diabetes in patients with periodontal disease.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of periodontal diseases is arrived at by thorough history taking, clinical and radiographic examination and special investigations. Particular features in relation to history are presence of relevant factors in medical history and smoking habit. Clinical examination allows assessment of plaque control, loss of gingival contour, swelling, recession of periodontal tissues, periodontal pocketing, furcation lesions and tooth mobility. The basic periodontal examination (see p. 182) provides an overview of the periodontal status. Detailed pocket charting should be carried out if advanced periodontitis is detected.

Pocketing

Periodontal pockets can be divided into the following:

False pockets

are due to gingival enlargement with the pocket epithelium at or above the amelocemental junction.

True pockets

imply apical migration of the junctional epithelium beyond the amelocemental junction and can be divided into suprabony and intrabony pockets. Intrabony are described according to the number of bony walls:

Pocket depths

are measured from the gingival margin to the estimated base of the pocket. Attachment levels are measured from a fixed reference point: the cement–enamel junction or margin of a restoration to the base of the pocket. Pockets are therefore dependent on the position of the gingival margin.

Periodontal probes

are the key instruments in detecting pockets. Numerous designs exist, and while individual preference will influence choice, it is sensible to reduce variability by selecting a single type of probe and using that type of probe throughout any one individual’s Rx. The use of the WHO probe for screening using the BPE index is described on p. 182. Patients who are identified as having advanced CP should then be investigated further, including probing around each tooth. The main other indicator of periodontal disease, bleeding, is also detected using a probe (gently), and again consistency with a single type of probe is necessary.

Probing variables

The depth of penetration depends upon:

It is now apparent that the measurement obtained with a probe does not correspond to sulcus or pocket depth. In the presence of inflammation a probe tip can pass through the inflamed tissues until it reaches the most coronal dento-gingival fibres, about 0.5mm apical to the apical extent of the junctional epithelium, i.e. an overestimation of the problem. The amount of penetration into the tissues varies directly with the degree of inflammation, so that, following resolution of inflammation, an underestimate of attachment levels may be given. Formation of a tight, long junctional epithelium following Rx may also give a false sense of security if probing measurements are not interpreted with a degree of caution. For this reason the term ‘probing pocket depth’ is preferred to pocket depth.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses