Evaluation of the effect of anesthesia is necessary before initiating the procedure.

Indications of anesthesia failure:

| The inferior alveolar nerve | Absence of the sign of Vincent | ||

| The buccal nerve |  |

Sensitivity of the buccal mucosa | |

| The lingual nerve | Sensitivity of the lingual mucosa |

Anesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve

Failure of nerve block anesthesia indicates that the anesthetic solution has not been injected into the mandibular foramen area prior to its penetration through the thickness of the ramus. Indeed, two reasons may explain this:

• Incorrect assessment of the anatomic position of the foramen

• Incorrect needle used for tissue penetration

The mandibular foramen

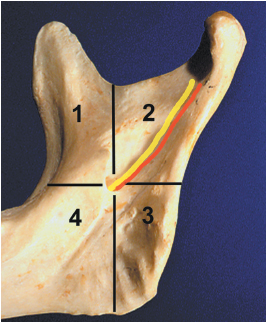

The foramen of the mandibular canal is located behind and under the lingula (Spix spine). It is the lowest point of the funnel-shaped crater through which the mandibular nerve and vessels pass (Fig 5-1).

This foramen is located in the middle of the mandibular branch (ramus):

• In the vertical dimension it is equidistant from the mandibular incisure (sigmoid notch) and the inferior border of the ramus

• In the horizontal dimension it is equidistant from the temporal crest and the posterior border.

The lingula sometimes forms an important bone protrusion, which masks the foramen (Fig 5-2a).

During growth—between the ages of 9 and 19 years—the mandibular foramen is located in a higher and more posterior position than it is in the adult. This therefore must be taken into account when administering anesthesia to an adolescent.

Physical examination of the ramus should be carried out both extraorally and inside the oral cavity (Figs 5-2b and 5-2c). The clinician faces the patient and locates the right ramus with the left hand and conversely the left ramus with the right hand as described below:

• The index and middle fingers are placed against the posterior border of the ramus.

• The little finger is placed against the inferior border.

• The thumb is placed in the vestibule, resting on the concave area of the bone ridge of the anterior ramus border under the dome of the cap of the coronoid process, which is covered by the temporal muscle.

• In the second stage, the tip of the thumb is moved forward inside the temporal groove against the temporal crest.

The needle is then directed toward the center of the ramus, regardless of its size (whether it is a child or an adult) and its penetration follows the line of the thumbnail. The syringe is held at the level of the contralateral premolars (Figs 5-3 and 5-4). The orientation of the dental arch should be ignored.

In the horizontal dimension, the arch axis does not correspond to the ramus axis. The arch axis is often located more than 1 cm inside the bone wall. If the path of the needle follows this axis, then bone contact may not occur and the anesthetic is released into the interpterygoid space (Fig 5-5).

In the vertical dimension, the penetration point of the needle cannot be determined in relation to the occlusal plane because the distance between the level of the occlusal plane and that of the foramen is not universal. The position of the canal foramen in relation to the occlusal plane varies significantly. A needle directed parallel to and at a distance of 5 mm from this plane meets the ramus under the lingula in 36% of cases (Bremer). Placing the index finger on the occlusal molar aspects in order to locate the needle’s penetration point may therefore not be the most appropriate method. In the vertical dimension, it is the position of the thumb, which should be placed in the concavity of the temporal groove, that will guide the clinician during tissue penetration (see Fig 5-3). The dimensions of the ramus must be accurately determined, especially where a posterior edentate situation exists; the clinician needs to evaluate the height and width of the ramus before undertaking infiltration.

Anesthesia instrumentation: Tissue penetration and related risks

• Cartridge syringe, with manual suction, mounted with a harpoon; or an Aspiject or Anthoject type of syringe, ensuring self-suction

• 35-mm needle, 50/100

• Anesthetic solution with an added vasoconstrictor used in healthy subjects (Madrid et al)

Many clinicians use only one type of needle for anesthesia: a periapical type of needle, 0.30 or 0.35 mm in diameter and 21 mm in length. This practice is derived from the idea that a thin needle allows painless penetration and causes less tissue trauma.

A thin and supple needle is often a source of failure for block anesthesia because the muscles and their aponeurosis may cause needle deviation. This is the case for the buccinator aponeurosis, which lines the muscle on its outer aspect. It may be approached tangentially, u/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses