chapter 5 Monitoring During Sedation

The word monitor comes from the Latin monere, meaning “to remind, admonish.” One definition of monitor is “to observe and evaluate a function of the body closely and constantly.”1 A second definition is “an apparatus which automatically records such physiological signs as respiration, pulse (heart rate and/or rhythm), and blood pressure in an anesthetized patient or one undergoing surgical or other procedures.”2

Monitoring appropriate physiologic functions of a patient during both sedative procedures and general anesthesia permits the early detection of adverse side effects that may be produced by drugs or by clinical actions, including hemorrhage or underventilation.3 Early detection of these problems allows corrective measures to be instituted at a time when they are more likely to effectively prevent serious complications from developing. Recognizing and treating an anesthesia urgency can prevent it from becoming an anesthesia emergency.

Since the first edition of this book in 1985, there has been a significant increase in emphasis placed on monitoring during sedation and general anesthesia. The first specific, detailed mandatory standards for minimal patient monitoring during anesthesia in medicine were developed by the Risk Management Committee of the Department of Anesthesia, Harvard Medical School, in Boston, Mass., in 1985.4 Although some of this increased emphasis stemmed from a normal elevation in the standard of care, a major impetus came from studies evaluating critical incidents occurring during anesthesia. It was demonstrated that up to 80% of these critical events were preventable and could be attributed to human error and a lack of vigilance.5,6 It was believed that the routine application of minimal monitoring devices would enable the detection of subtle physiologic changes, permitting measures to be taken before the situation deteriorated into a catastrophe.7 In 1986 the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Committee on Standards of Care8 developed the “ASA Standards for Basic Intraoperative Monitoring” as a national standard. Before the Harvard and ASA standards, formal guidelines for monitoring during sedation in dentistry were limited to a few states that had previously instituted regulations defining the practice of anesthesia (general anesthesia and sedation) in dentistry, in essence providing guidelines for treatment. There was a considerable increase in implementation of guidelines in the years immediately following their publication. By July 1987, 30 states had enacted regulations governing the use of general anesthesia in dentistry, and 27 were regulating parenteral sedation.9 By June 1994, these figures had become 48 for general anesthesia and 46 for parenteral sedation.10 In April 2008, the American Dental Association (ADA) was aware of 47 states requiring the dentist to obtain a permit to administer general anesthesia (though all 50 have educational requirements in place) and 47 for parenteral sedation.11

Oral sedation regulations vary considerably. Oral sedation in children: The ADA was aware of three states having enteral sedation permits specific to administration to minors (e.g., Louisiana has a permit entitled “restricted” that allows the dentist to administer to adults only). Three other states mention within their enteral sedation permit language: “additional training requirements to administer to children.” Three other states have language within their enteral sedation laws that require the dentist to have a parenteral sedation permit to administer enteral sedation to children.11

Oral sedation, in general to any patient. Absent occasional references to PALS (pediatric advanced life support) for dentists treating pediatric patients, the ADA is aware of 14 states that have fairly straight forward options for enteral permits that do not mention additional training for administration to pediatric or minor patients.11

Specific requirements for monitoring during parenteral sedation or general anesthesia are usually described in these regulations. In addition, specialty organizations within dentistry have produced sedation-anesthesia guidelines for use within their specialty. Guidelines have been forthcoming from the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons,12 the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry,13 and the American Academy of Periodontology.14 The national governing bodies of dentistry in several countries have also produced guidelines for the use of parenteral sedation and general anesthesia.15,16

The Subcommittee on Standards of Care of the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology (ADSA)17 has created monitoring guidelines that take into account the unique aspects of sedative and anesthetic care delivery in a dental office setting. These guidelines represent an amalgamation of the Harvard and ASA standards and continue to stress the triad of oxygenation, ventilation, and circulation (the airway, breathing, and circulation of basic life support). The ADSA monitoring guidelines are presented in Box 5-1.

Box 5-1

American Dental Society of Anesthesiology Guidelines for Intraoperative Monitoring of Patients Undergoing Conscious Sedation, Deep Sedation, or General Anesthesia

The terminology recognized by the American Dental Association (ADA) for various methods of delivery of nonregional anesthetics and sedatives and the anticipated clinical effect has been previously approved by the House of Delegates in 1985. These include, but are not limited to, the following: enteral, parenteral, conscious sedation, deep sedation, and general anesthesia. The standards endorsed by the ADA in these guidelines apply to all nonregional dental anesthesia care. They are designed to encourage a high level of quality care in the dental office setting. It should be recognized that emergency situations may require that these standards may be modified on the basis of the judgment of the clinician(s) responsible for the delivery of anesthesia care services. Changing technology; individual states’ rules, regulations, or laws; and regulations developed by the parent organization, the American Dental Association, may also supersede the standards listed herein. It should also be recognized that there may be certain situations whereby the standards may be clinically impractical* (e.g., combative patient, emergency surgery) and that adherence to the standards is no guarantee of successful outcome.

Standard I: Qualified Personnel

Qualified personnel shall be present in the operating room during the anesthesia period.

Objectives

Standard III: Ventilation

Methods

Standard IV: Circulation

Methods

Standard V: Body Temperature

During the anesthesia period, the patient’s body temperature may need to be evaluated.

Terminology

Continual: Repeated regularly and frequently in steady succession

Continuous: Prolonged without any interruption at any time

May or could: Indicates freedom or liberty to follow a suggested alternative

Qualified personnel: Persons with training and credentials to perform specific tasks

Shall or must: Indicates imperative need and/or duty: an indispensable item; mandatory

Should: Indicates the recommended manner to obtain the standard; highly desirable

In a report comparing 43 cases of morbidity and mortality (M & M) from sedation and general anesthesia in the dental office environment, the M & M were characterized as occurring in a young, healthy patient in whom multiple pharmacologic agents were used with limited monitoring and resuscitative efforts. Heart rate was not monitored in 68%, respiration in 77%, blood pressure in 77%, tissue oxygen (O2) saturation in 92%, and heart rhythm in 96%.18 The authors concluded, and other experts agreed, that lack of adequate monitoring is a key factor in the majority of morbid and mortal events.18,19 If, as Jastak19 has stated, “subtle trends in vital signs are not detected because appropriate monitoring is not used, the morbid event eventually recognized by the practitioner is often the last in a series of physiologic distress signals, and, of course, results in the clinician’s response being too little and too late.” The implementation of monitoring guidelines has been associated with improved anesthesia care and a downward adjustment of anesthesia malpractice insurance premiums.20,21

Devices are termed invasive and noninvasive. When possible, monitors should be noninvasive. Indeed, for routine monitoring, noninvasive monitoring is essential. Invasive devices hurt, their placement is time consuming, they are costly, and their use has unacceptable risks in many instances.3 Invasive monitors include arterial lines for measurement of blood gases and lines for central venous pressure. Although they provide highly accurate measurements of important physiologic parameters, there is an increased risk associated with their use in that complications are more likely to develop because of the very nature of the techniques. In addition, invasive monitors are often quite time consuming to prepare for use. In the outpatient dental or surgical environment, where only sedation techniques are employed, the use of invasive monitors is rarely justified. However, in cases in which inpatient general anesthesia is to be used, particularly when the patient is classified as ASA 4, 3, or 2 (see Chapter 4), the use of additional, highly accurate monitoring procedures is warranted. Noninvasive monitors are easier to use and are not associated with increased risk. Some may suffer from a diminished level of accuracy (compared with invasive monitoring of the same physiologic parameter). However, devices such as the pulse oximeter and capnograph (end-tidal carbon dioxide [CO2] monitors) have been shown, by and large, to be quite accurate. For outpatient sedation as used in dentistry and medicine, noninvasive devices prove to be quite acceptable for monitoring of patients during and after treatment. The requirements of the ideal monitoring device are as follows22:

ROUTINE PREOPERATIVE MONITORING

Before treatment of any dental or medical patient, vital signs should be recorded as a part of the routine pretreatment patient evaluation (see Chapter 4). Vital signs recorded at this pretreatment visit include blood pressure, heart rate and rhythm, and respiratory rate. Additional vital signs to be monitored as indicated include temperature, height, and weight.

These values should be recorded on the patient’s chart (Figure 5-1) and serve as baseline values, against which values obtained during treatment may be compared. Baseline vital signs should be recorded at a nonthreatening time when they are likely to be more nearly “normal” for that patient. A patient’s initial visit to a dental office, a time when no invasive dental procedure is planned, is likely to provide reliable baseline values.

Pulse (Heart Rate and Rhythm)

Monitoring of the pulse (heart rate and rhythm) is reviewed in Chapter 4. Monitoring of the pulse is recommended for all patients as a part of their routine preoperative evaluation. Values below 60 or greater than 110 beats per minute (in the adult) should be evaluated before treatment is started.

The heart rate and rhythm may be measured manually or by electronic methods. When the heart rate is recorded manually, the fleshly portions of one or two fingers are gently placed over a superficial artery for at least 30 seconds (preoperative recording). When monitoring takes place during sedation or general anesthesia, a period of 10 to 15 seconds is usually employed, although 30 seconds is suggested. Arteries that are accessible for monitoring of the pulse are listed in Table 5-1. The radial and brachial arteries are most often used in routine situations. The superficial temporal artery is frequently used during general anesthesia. The facial or labial arteries are accessible when working in or around the oral cavity. Palpation of the carotid artery is usually reserved for emergency situations.

| Artery | Location |

|---|---|

| Radial | Ventrolateral wrist |

| Brachial | Medial antecubital fossa |

| Carotid | Groove between trachea and sternocleidomastoid muscle in neck |

| Labial | Upper lip |

| Facial | Cheek |

| Superficial temporal | Anterior to tragus of ear |

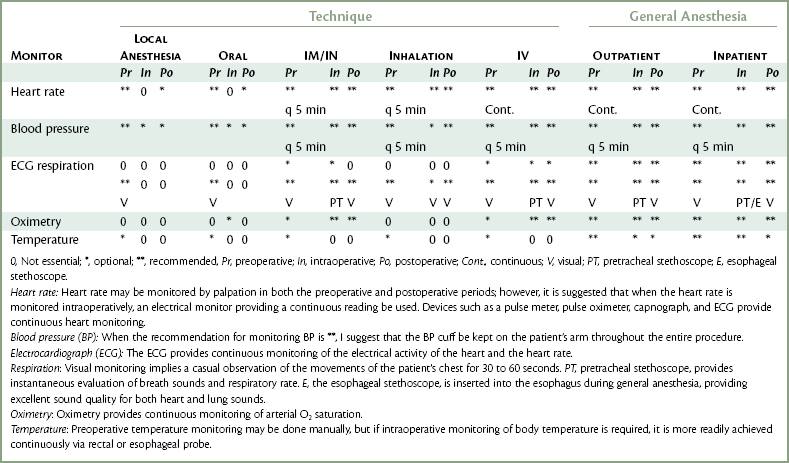

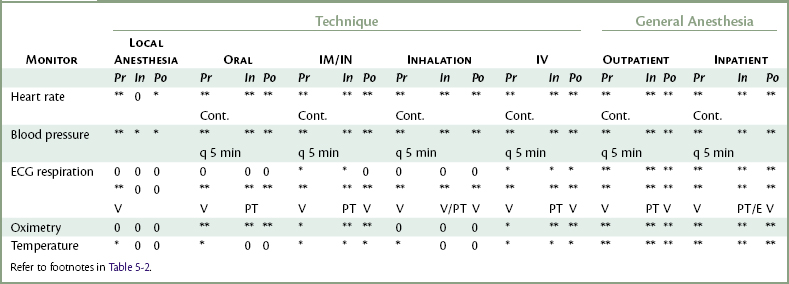

In addition to their primary function(s), many monitoring devices, such as the pulse oximeter, automatic vital signs monitor, and the electrocardiograph (ECG), also measure the heart rate. Either a digital display or a graph on the oscilloscope is provided. Recommendations for heart rate monitoring are found in Tables 5-2 and 5-3.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses