Chapter 5

I’ve Got a Clicking Joint

History

Mrs Smith is a 30-year-old woman who complains of occasionally painful clicking from her right temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

The history of her present complaint is that a painless click had been present for 14 years. This arose with sudden onset and no initiating event. Ever since she has had consistent clicking from the right TMJ which never comes and goes but does vary in intensity. She has never experienced locking. The clicking is worse (louder) with function, as in when eating. Originally it was not present when she talked but now it is. She reported that the click was worse in the morning when she woke up and her jaw felt stiff. This stiffness was present for only an hour or so and then her movement returned to normal. The click, however, remained.

More recently the click has become ‘uncomfortable’ and she said that her bite now ‘feels odd’. She has noticed that, when she stands in front of a mirror and opens her mouth, her jaw does not move in a straight line.

Mrs Smith attended her general medical practitioner who suggested referral for a dental opinion.

She has no medical history of note and is not taking any medication. She was a fit and healthy person. She had, however, been stressed at work over the last 2 years because she was worried about possible redundancy. She is a secretary and spends a lot of time on the telephone and now finds her click embarrassing because it has occasionally started to happen while talking and customers have questioned her about it.

Examination

She has a class I, basal bone and incisal relationship.

She can open to well within the normal range (40 mm) in the vertical dimension. She can move equally easily to both the right and the left sides to over 10 mm. There is no discomfort on vertical or lateral jaw movements.

She has a transient deviation when examining the pathway of opening. Her mouth deviates to the right when opening wide, but after this deviation the pathway of opening returns to the vertical.

She has a midcycle reciprocal (opening and closing) click from the right TMJ. The opening click is audible to others, and is louder than the closing click which could be heard only with the use of a stethoscope.

On intraoral examination, there was ridging of the buccal mucosa and abnormal attrition of her teeth, especially the upper and lower left and right canines, and the buccal cusp tip of the lower left second premolar and first molar.

The temporalis and masseter muscles were examined by palpation and the lateral pterygoid against resistance. There were no obvious areas of muscle tenderness but opening against resistance was ‘uncomfortable’. She said that her face had on occasion been aching when she wakes in the morning, as it had today.

The TMJs were examined by direct palpation in the preauricular region and via the external auditory meatus. There was no evidence of TMJ tenderness on lateral palpation but the right TMJ was tender when examined via the external auditory meatus with her mouth both open and closed.

On examination of the occlusion, she appeared to have centric relation occlusion; there were no premature contacts and no slide from centric relation to centric occlusion. She had canine guidance on both the right and the left sides. There were interferences on the working side involving the right premolars and first molar and there were interferences on the non-working side involving the upper and lower left molars.

Radiographs

These are not usually relevant. A radiograph should be taken only if it is essential for the dentist to reach a diagnosis or if the treatment plan depends upon the outcome of it. In this instance the clinician would expect the radiograph to be perfectly normal, because it is the soft tissues of the TMJ that are involved.

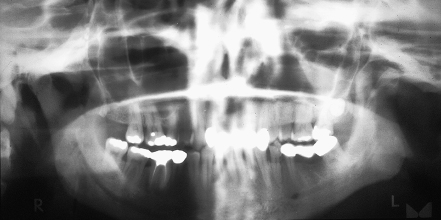

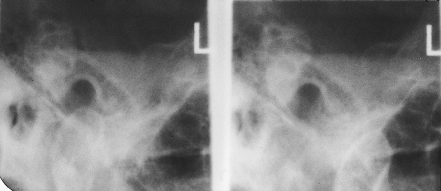

The normal radiographs used to visualise the TMJ are a dental panoramic tomogram (DPT) (Figure 5.1), or a transpharyngeal (Figure 5.2) or transcranial oblique lateral (TOL) view of the skull (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.1 Dental panoramic tomographs used to show condyles.

Figure 5.2 Transpharyngeal view of the mandibular condyle.

Figure 5.3 Transcranial oblique lateral radiographs.

As both the articulating surfaces of the joint and the disc are fibrous tissue, these components cannot be visualised on a radiograph. Only a small portion of the articulating surface is visible and, especially with the TOL, the articulating surfaces shown are not load-bearing parts of the joint. There must be approximately 40% decalcification before bony erosions can be visualised. The joint space cannot be estimated, and the position of the disc cannot be identified.

For all these reasons radiographs of TMJs are of limited value, as are other scanning methods unless invasive treatment is being planned.

According to (IR(ME)R) 2000 guidelines, it is your responsibility to minimise the radiation exposure for patients and radiographs should be taken only when clinically essential.

Other Special Tests

In this lady’s case the click disappeared on anterior posturing of the mandible.

When she opened and closed her mouth from her habitual bite, the click was consistently present. It was louder on opening and softer on closing but was present on every opening and closing cycle. When she postured her mandible forwards until the incisors were in an edge-to-edge relationship, and opened and closed from this protrusive position, the click disappeared after the first opening cycle.

Why Do TMJs Click?

First think about the anatomy of the joint.

The components of the TMJ involve the fossa in the petrous part of the temporal bone and the condylar process of the mandible. Interposed between the two bony components is the intra-articular disc which is a sheet of fibrous tissue. It has attachments circumferentially around the head of the condyle. There is an elastic attachment to the area of the squamotympanic fissure on the base of the skull, and a fibrous attachment to the posterior part of the neck of the condyle. Anteriorly the disc is confluent with and inserts into the superior pterygoid muscle (superior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle).

The disc is divided into three zones: a thick posterior band, a thin intermediate zone and a slightly thicker but narrow anterior band. The shape of the disc is described as being similar to a ‘jockey’s cap’, with the peak anteriorly in the region of the pterygoid muscle attachment (Chapter 2). This disc therefore divides the joint capsule into two spaces: the superior and the inferior joint spaces. The inferior joint space is between the underside of the surface of the disc and the head of the condyle. The superior joint space is between the superior surface of the disc and the articular fossa.

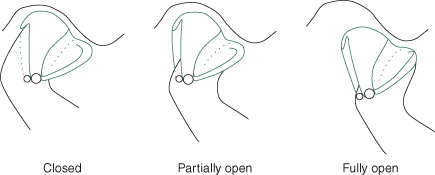

During the first phase of mouth opening, condylar movement in the joint capsule is purely rotational and occurs in the inferior joint space. The first part of mouth opening is principally a ‘hinge’ action and rotation occurs between the head of the condyle and the inferior surface of the disc. The amount of mouth opening that can be attained during this phase is remarkably consistent and is between 17 and 20 mm.

The second phase of joint movement is a translational or sliding movement which occurs mainly in the superior joint cavity. During this phase of movement, the head of the condyle moves forwards from resting against the posterior band of the disc, slides over the intermediate zone, and finally on to the anterior band of the disc as the whole complex slides down the anterior slope of the articular eminence.

The disc is pulled forward by the superior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle and the posterior attachment to the squamotympanic fissure, which is elastic, allows stretching of this portion of the disc, thereby allowing it to remain interposed between the two bony components of the joint at all phases of movement. During closure of the mouth, the reverse process occurs and the elastic recoil of the posterior part of the bilaminar zone of the disc helps to pull it back into place (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Normal condyle disc fossa relationship during mouth opening.

(From Davies SJ, Gray RJM. The pattern of splint usage in the management of two common temporomandibular disorders. Part I: The anterior repositioning splint in the treatment of disc displacement with reduction. Br Dent J 1997;183:199–203, with permission.)

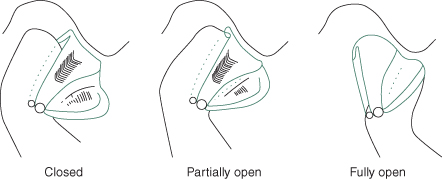

If the joint is damaged or overloaded in any way, there is a tendency for an increased tonicity in the pterygoid muscle and this tends to pull the disc forwards. The rotational phase of mouth opening still occurs as normal but as the translation phase starts, the head of the condyle slides forwards and encounters the disc in the displaced position and it impacts against the thicker posterior band of the disc. Friction is then built up until the head of the condyle ‘jumps past’ this portion of the disc which causes an audible release of energy, which is the click (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5 Anteriorly displaced reducing disc in relation to condyle during mouth opening.

(From Davies SJ, Gray RJM. The pattern of splint usage in the management of two common temporomandibular disorders. Part I: The anterior repositioning splint in the treatment of disc displacement with reduction. Br Dent J 1997;183:199–203, with permission.)

The click appears to be the sound produced by the sudden distraction of the opposing wet surfaces of the disc and condyle. It has also been proposed that TMJ clicking occurs because an abnormal relationship between the TMJ components might obstruct the normal movement of the synovial fluid during function, causing fluid to trap under pressure.

The reason that clicking disappears with anterior posturing of the mandible is that bringing the mandible forwards re-establishes a ‘normal functional’ relationship between the position of the disc and the head of the condyle. This then releases the abnormal fluid pressure that resulted in the click.

When Do TMJs Click?

There are two main situations when TMJ clicking occurs. The first is clicking secondary to myofascial pain. This is the click that is present in the patient who may parafunction (clench or grind) during sleep.

In many people who exhibit a parafunctional activity, it is nocturnal and at its most pronounced in the rapid eye movement period of sleep. This is the lighter plane of sleep before waking.

Due to the general increased tonicity in the muscles, there is a tendency for the superior pterygoid muscle to/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses