5 Fibrous, Gingival, Lipocytic, and Miscellaneous Tumors

Fibrous Lesions

Fibroma (“Bite” or “Irritation” Fibroma, Fibroepithelial or Fibrovascular Polyp) and Giant Cell Fibroma

Clinical Findings

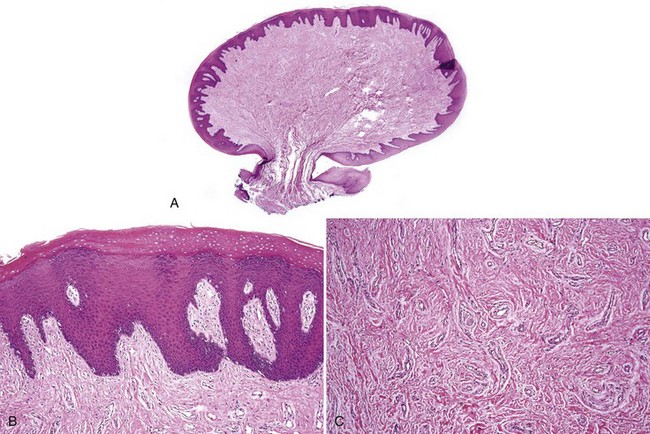

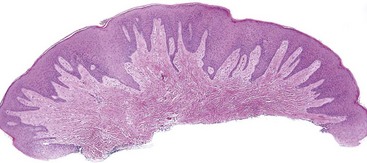

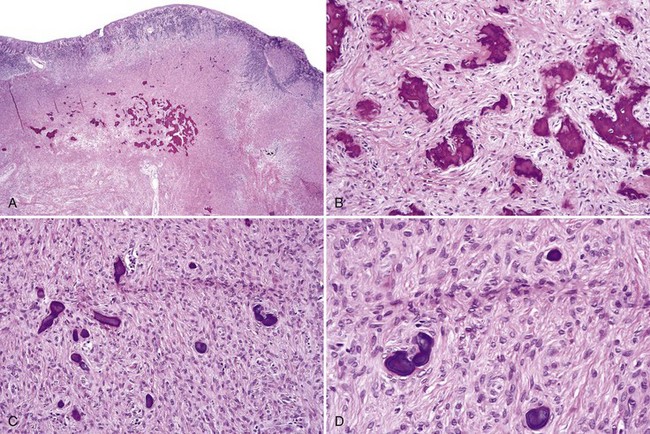

• Dome-shaped nodule or papule; may be white/keratotic, mucosa-colored or ulcerated and is seen in areas readily traumatized by biting (i.e., buccal mucosa, lateral tongue, and lower labial mucosa) or on gingiva(where plaque accumulates) (Fig. 5-1, A-D).

• Variant giant cell fibroma has a papillary surface and is usually located on gingiva or tongue (see Fig. 5-1, E).

• Sclerotic fibromas may be seen as focal sporadic lesions or in patients with tuberous sclerosis, associated with loss of heterozygosity of the PTEN gene.

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

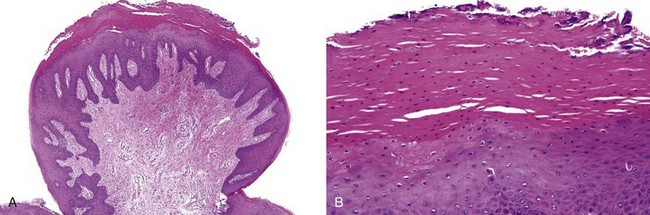

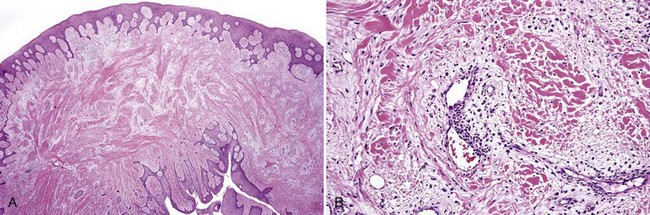

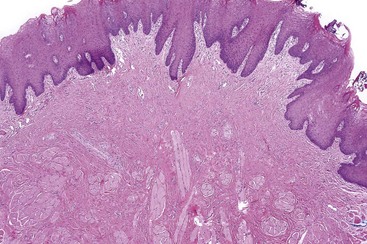

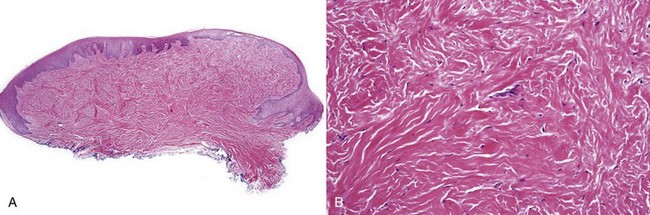

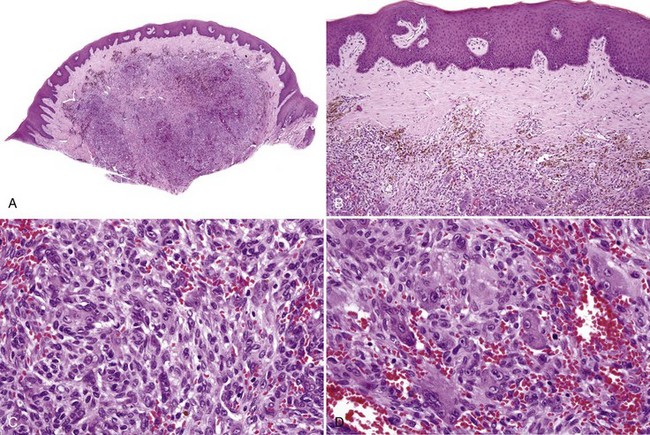

• Nodular proliferation of fibrous tissue is associated with variable vascularity, hyperparakeratosis or orthokeratosis, ulceration, inflammation, epithelial hyperplasia, or atrophy (Figs. 5-2 and 5-3); variable myxoid/mucinous change (Fig. 5-4); or entrapment of muscle (Fig. 5-5).

• Sclerotic fibroma (also called storiform collagenoma) has dense, hyalinized bands of keloidal collagen with a slight storiform pattern and stellate and fusiform fibroblasts with clefts between collagen fibers; lesions are occasionally positive for factor XIIIa and CD34 (Fig. 5-6).

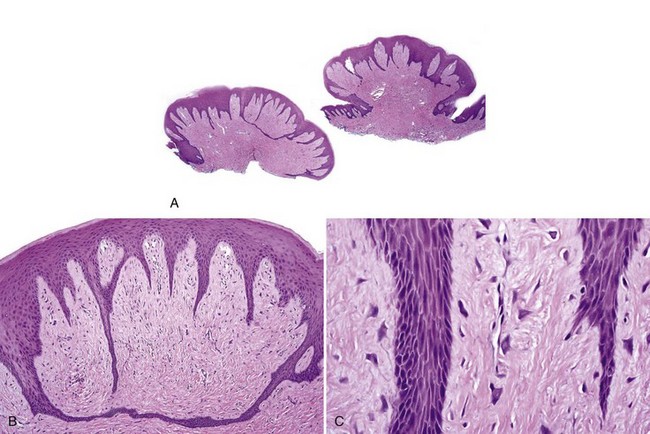

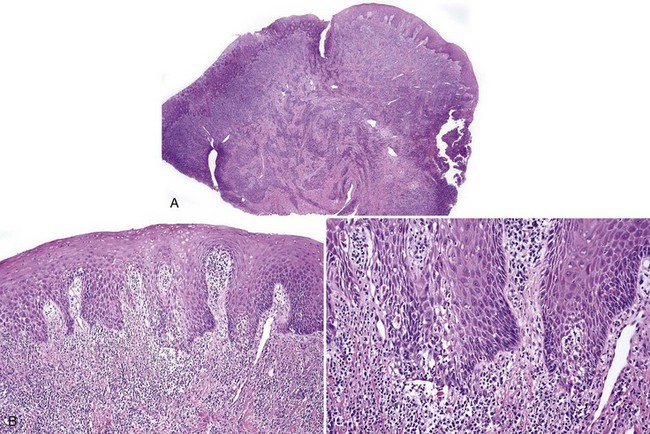

• Giant cell fibroma exhibits papillary surface, epithelial hyperplasia forming spiky rete ridges; giant, stellate, multinucleated fibroblast-like cells that sometimes show cytoplasmic positivity for smooth muscle actin suggesting differentiation toward myofibroblasts; and keloid-like dense collagen. Mast cells are often present (Figs. 5-7 and 5-8) similar to fibrous papule of the nose.

• Fibromas of the anterior hard palate often contain cartilage and branches of the nasopalatine neurovascular bundle (Fig. 5-9).

Alawi F, Freedman PD. Sporadic sclerotic fibroma of the oral soft tissues. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:182-187.

Fernandez-Flores A. Solitary oral fibromas of the tongue show similar morphologic features to fibrous papule of the face: a study of 31 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:442-447.

Houston GD. The giant cell fibroma: a review of 464 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;53:582-587.

Magnusson BC, Rasmusson LG. The giant cell fibroma. A review of 103 cases with immunohistochemical findings. Acta Odontol Scand. 1995;53:293-296.

Metcalf JS, Maize JC, LeBoit PE. Circumscribed storiform collagenoma (sclerosing fibroma). Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:122-129.

Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:266-271.

Gingival Masses

• Reactive/inflammatory gingival nodules, solitary or diffuse

• Peripheral (extraosseous) odontogenic cysts and tumors

• Soft tissue tumors (such as nerve sheath or smooth muscle tumors, discussed in Chapter 6)

Reactive/Inflammatory Gingival Nodules

Clinical Findings

• Young patients in second to fourth decades; nodular masses on the marginal gingiva, often maxillary anterior region; pink, erythematous, dusky purple, or ulcerated; may be painful and, if vascular, will bleed; underlying bone may show “saucerization” of bone (especially with giant cell granuloma) (Fig. 5-10)

• Peripheral giant cell granulomas least common; tend to occur in older adults

• Parulis (“gum-boil”) occurs on the attached gingiva; has a punctum and underlying tract that leads to the infected tooth (see later)

• Up to 5% of pregnancies associated with gingival pyogenic granulomas (granuloma gravidarum)

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

Pluripotent cells in the gingival tissues when traumatized or irritated (usually by accumulation of dental calculus or bacterial plaque, rough edges of restorations, or presence of implants) differentiate toward endothelial cells, fibroblasts, osteoblasts, or osteoclast-like cells, giving rise to four distinct histologic entities or combinations thereof. Estrogen and progesterone causes overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor in granuloma gravidarum. See Table 5-1 and Figures 5-11 to 5-19 for histopathologic features.

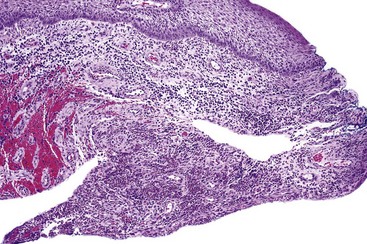

• Parulis consists of a mass of edematous granulation tissue with many acute and chronic inflammatory cells and tracts lined by neutrophils (Figs. 5-20 to 5-22); they are often mistaken for mucoceles (which do not occur on the attached gingiva).

| Diagnosis | Histopathology |

|---|---|

| Fibroma (fibrovascular hyperplasia/polyp) Giant cell fibroma |

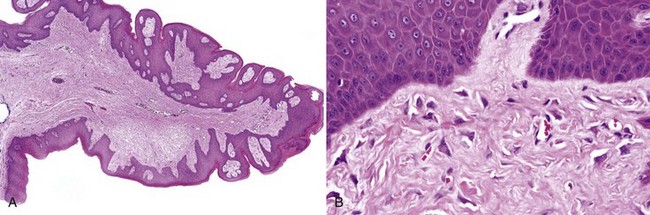

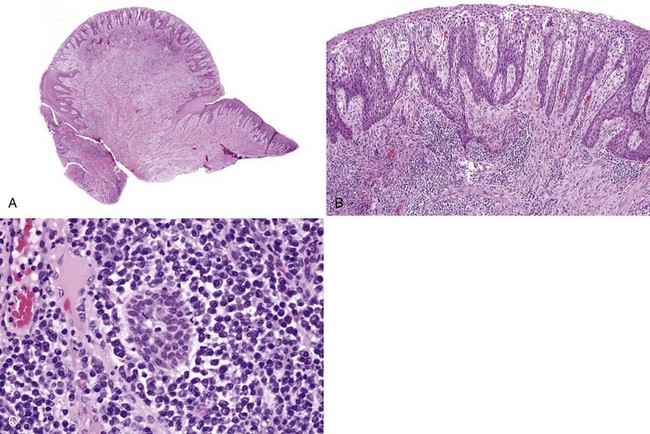

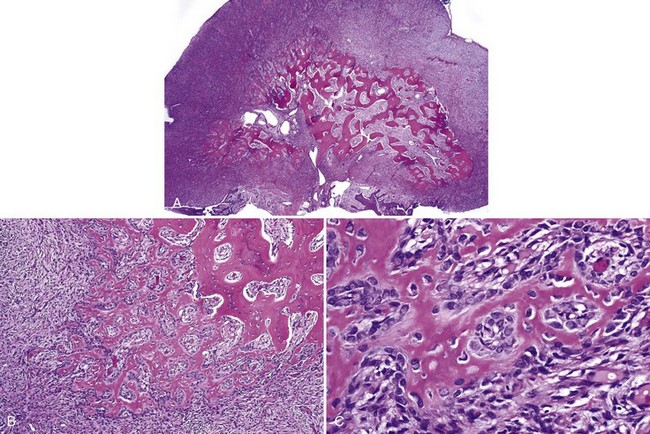

• Lobular or nonlobular proliferation of endothelial cells and small, dilated capillaries; often ulcerated and inflamed (see Fig. 5-13, A)

• Endothelial cells show reactive atypia—focal “hobnail” pattern, enlarged nuclei with prominent nucleoli, some mitotic activity (see Fig. 5-13, B and C)

• May see fibrosis depending on stage of organization (see Fig. 5-14)

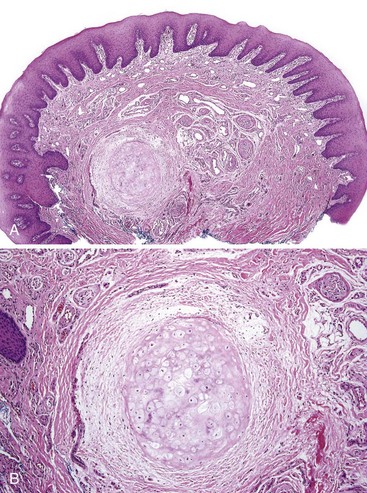

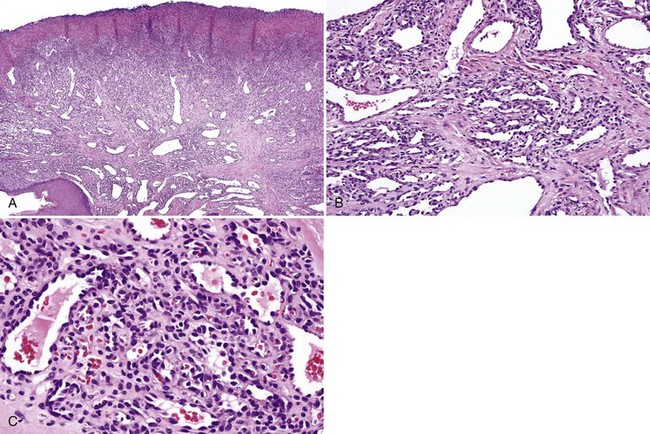

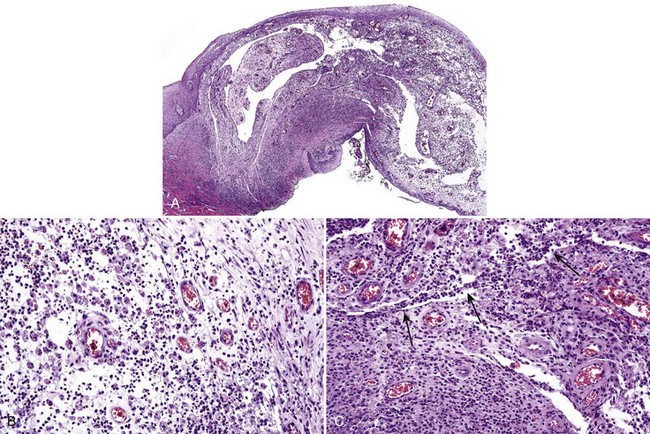

• Cellular proliferation of spindled fibroblast–like cells with ovoid nuclei that have dispersed chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli; sometimes only subtle osteoid deposits or focal calcifications are present (see Fig. 5-15, A and B)

• Osteoid, woven bone, or cementum droplets laid down by spindle cells although osteoblastic rimming sometimes seen (see Figs. 5-15, C and D, and 5-16)

• May see clusters of multinucleated giant cells similar to peripheral giant cell granuloma (see Fig. 5-17)

• Bone morphogenetic protein identified in the spindled fibroblast-like cells

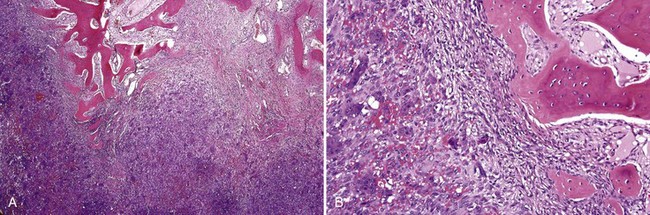

• Proliferation of mononuclear and multinucleated giant cells (osteoclast-like or foreign body type) usually in sheets; giant cells contain 10-20 nuclei in a central location; mitoses may be seen in mononuclear cells; fresh hemorrhage and hemosiderin deposits, especially beneath the grenz zone (see Figs. 5-18, 5-19)

• May see concomitant osseous prosoplasia similar to peripheral ossifying fibroma

Differential Diagnosis

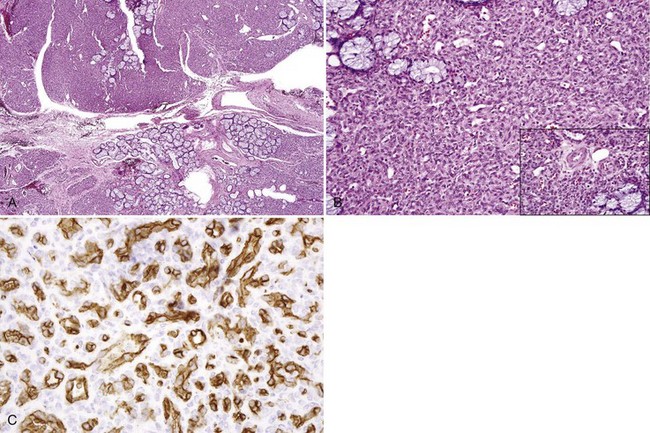

• True infantile hemangiomas show a lobular proliferation of endothelial cells and capillaries that are positive for glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) (Fig. 5-23)

• Peripheral odontogenic fibroma produces dentinoid rather than cementum or osteoid and epithelial islands are always present, distinguishing this from peripheral ossifying fibroma (see later).

• Aggressive central (intraosseous) giant cell granulomas may erode through bone; radiographs differentiate them from peripheral (extraosseous) lesions.

Buchner A, Hansen LS. The histomorphologic spectrum of peripheral ossifying fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:452-461.

Buchner A, Shnaiderman-Shapiro A, Vered M. Relative frequency of localized reactive hyperplastic lesions of the gingiva: a retrospective study of 1675 cases from Israel. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:631-638.

Carvalho YR, Loyola AM, Gomez RS, Araujo VC. Peripheral giant cell granuloma. An immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Oral Dis. 1995;1:20-25.

Epivatianos A, Antoniades D, Zaraboukas T, et al. Pyogenic granuloma of the oral cavity: comparative study of its clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features. Pathol Int. 2005;55:391-397.

Giunta JL. Gingival fibrous nodule. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:451-454.

Gordon-Nunez MA, de Vasconcelos Carvalho M, Benevenuto TG, et al. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a retrospective analysis of 293 cases in a Brazilian population. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2185-2188.

Hirshberg A, Kozlovsky A, Schwartz-Arad D, et al. Peripheral giant cell granuloma associated with dental implants. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1381-1384.

Katsikeris N, Kakarantza-Angelopoulou E, Angelopoulos AP. Peripheral giant cell granuloma. Clinicopathologic study of 224 new cases and review of 956 reported cases. Int. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;17:94-99.

Ono A, Tsukamoto G, Nagatsuka H, et al. An immunohistochemical evaluation of BMP-2, -4, osteopontin, osteocalcin and PCNA between ossifying fibromas of the jaws and peripheral cemento-ossifying fibromas on the gingiva. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:339-344.

Yuan K, Wing LY, Lin MT. Pathogenetic roles of angiogenic factors in pyogenic granulomas in pregnancy are modulated by female sex hormones. J Periodontol. 2002;73:701-708.

Diffuse/Multifocal Gingival Hyperplasia

Clinical Findings

• Seen in patients with poor oral hygiene and hormonal changes (e.g., puberty and pregnancy), and in patients on medications such as phenytoin, valproic acid, calcium channel blockers, and cyclosporine

• Diffuse, often slightly nodular enlargement of the gingiva of varying severity (Fig. 5-24, A and B); leukemic infiltrates may have a similar clinical appearance (see Fig. 5-24, C)

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

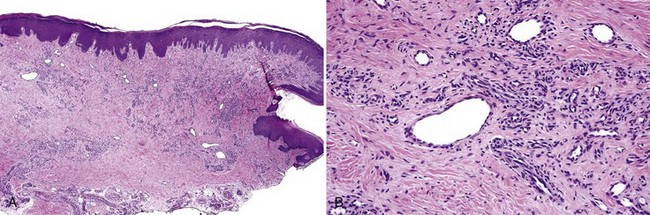

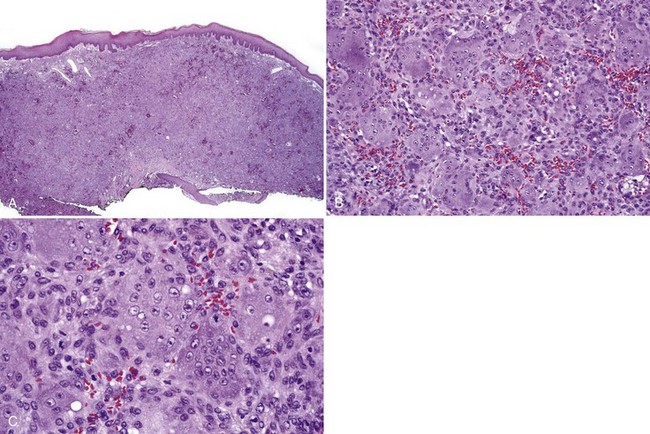

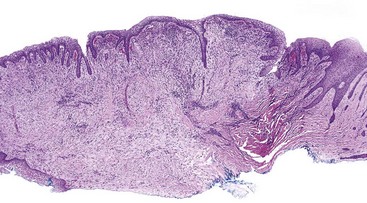

• Fibrovascular and epithelial proliferation with variable chronic inflammation usually plasmacytic; cytoid bodies sometimes are present if there is prominent spongiosis (Figs. 5-25 and 5-26).

• “Test-tube” rete ridges have been reported in patients on phenytoin and also are seen in patients with conventional non–medication-associated gingival hyperplasia.

Differential Diagnosis

• Presence of an atypical infiltrate should raise suspicion for acute myeloid or monocytic leukemia.

• Presence of pools of eosinophilic material (fibrin that is positive with phosphotungstic acid-hematoxylin) that fills the lamina propria should raise suspicion for ligneous gingivitis/periodontitis, a disorder of plasminogen activator deficiency (Figs. 5-27 and 5-28).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses