CHAPTER 5 DIVERSITY, SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES, AND COMMUNICATION IN ORAL HEALTH CARE

We have witnessed extraordinary progress in health care during the last century. Life expectancy has increased dramatically, and a host of medical conditions have been conquered by new biomedical technologies. In the area of oral health, dental caries have been sharply reduced by the introduction of fluoridation, and we no longer expect adults to become edentulous in middle age. As we enter the new millennium, there is a general sentiment that nothing is beyond the scope of science. However, not all Americans have benefited from recent scientific advances. In fact, as the vanguard of health care has advanced, the gaps between the haves and have-nots have become even more pronounced and disturbing. Barriers to oral health care exist. They range from the costs of care and cultural factors related to health beliefs and other psychosocial variables to intrinsic characteristics of the health care system itself. This chapter focuses on the interrelationships between sociocultural factors and health behaviors. It examines the cultural factors themselves, as well as health communication and the importance of cultural competence for the dental professional in achieving the goals of Healthy People 2010, namely oral health promotion and the reduction of oral health disparities.1

DEMOGRAPHICS

The demographic characteristics of the United States are changing rapidly. In 1990 approximately 24.3% of the population consisted of members of ethnic minority groups; by 2000 that number had grown to 28.7%.2 Between 1990 and 2000 the black population increased from 11.8% to 12.2% of the total population, Hispanics from 9% to 11.9%, and Asian and Pacific Islanders from 2.8% to 3.8%. Over the same period of time, the white population fell from 75.7% to 71.3% of the total. According to the latest census, 1 of every 10 Americans is foreign born. It is also projected that by 2050 minority-ethnic subpopulations will make up 47.5% of the total population, and that by 2056 whites will be a minority in the United States.3 In short, the cultural landscape of the United States will undergo seismic changes.

UTILIZATION OF ORAL HEALTH SERVICES

It is commonly accepted that the utilization of professional dental care is essential to achieve and maintain good oral health. The Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health maintains that almost everyone in the United States will experience some form of oral disease over the course of his or her lifetime.4 To prevent and combat the spread of oral disease, both prophylactic and restorative dental care is administered regularly and proficiently. There is an inverse correlation between unmet dental needs and utilization: that is, people who do not utilize dental care have higher rates of dental problems than those who do.

The most common measure of dental care utilization is the report of at least one dental visit in the past year. The proportion of the population over 2 years old with a dental visit in the past year increased from 57.1% in 1986 to 65.1% in 1997.5,6

Contrasting data from the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey 1996 (MEPS) indicated that only 44% of the population over 2 years of age visited a dentist in 1996.7 The Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health notes that there is substantial discrepancy in estimates of dental care utilization because of differences in definitions and sampling methodologies.3 However, virtually all estimates confirm marked disparities in utilization and unmet needs associated with demographic variables. The factors that affect utilization of dental services are complex. Trends over the past two decades reveal that family income, dental insurance coverage, and education level are positively correlated with the utilization of dental care.1,4,5 On the other hand, age is inversely correlated with utilization among adults.

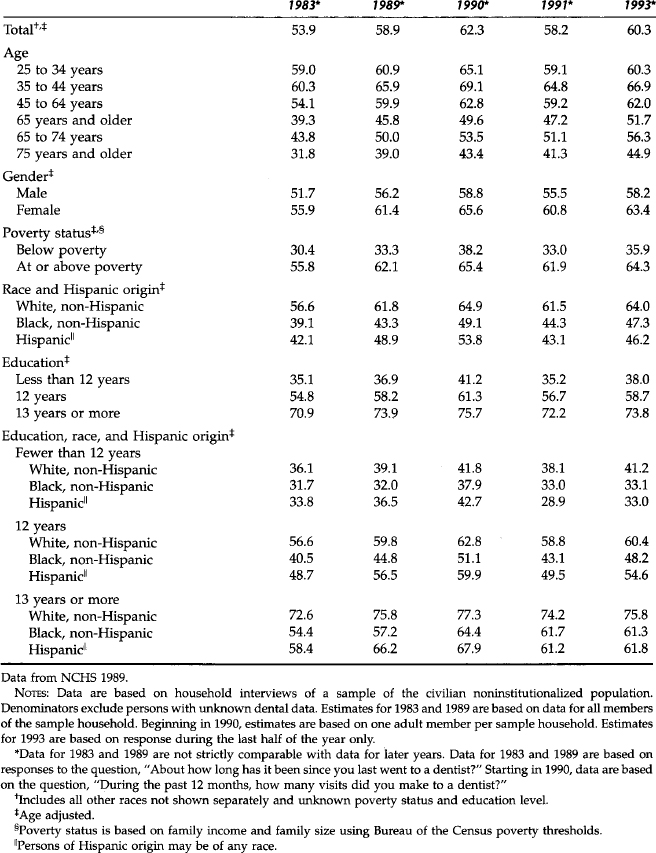

Table 5-1 illustrates these trends in oral health utilization and the health disparities by race/ethnicity.8 Ethnicity is also significantly associated with dental care utilization. Historically, blacks and Hispanics have had lower rates of utilization than whites. The table illustrates that 64% of whites versus 47% of blacks visited the dentist in the past year. The MEPS data indicate comparable disparities between whites and blacks (50% versus 27%, respectively).7 The consistent disparity is remarkable when one considers other associated variables. For example, although race/ethnicity is correlated with educational level, controlling for the latter does not nullify the disparity in dental care utilization between blacks and Hispanics versus whites.

ACCESS TO ORAL HEALTH CARE

Utilization of and access to care are mediated by a myriad of personal, cultural, and institutional factors. In the Institute of Medicine’s report entitled Access to Health Care in America, access to oral health care is defined as “the timely use of oral health services to achieve the best possible health outcome.”9 Three primary barriers to health care were identified—structural, financial, and personal/cultural.10 Structural barriers include the shortage of health care providers and lack of facilities in a community. Financial barriers are related to a patient’s ability to afford care; lack of insurance or underinsurance is a major obstacle for many patients. Personal barriers include individual characteristics such as sexual orientation, language, and education.

Economics plays a critical role in health care. The cost of dental care and the availability of insurance coverage have a profound impact on the utilization of health care services. Substantial disparities in health insurance coverage exist among different population groups. For adults under age 65 years, 34% of those below the poverty level are uninsured. Among the nonelderly population, approximately 33% of Hispanic persons lacked coverage in 1998, a rate that is more than double the national average.1 The uninsured use fewer health care services than do insured individuals. Paradoxically, individuals with public insurance (e.g., Medicaid) have higher rates of hospitalization and physician visits than privately insured individuals because of inadequate regular, preventive care.11,12 Extending the benefits of private insurance to uninsured individuals would significantly increase utilization rates of services by uninsured patients.13

Andersen14 has emphasized that dental care is more discretionary than other types of health services and is therefore more likely to be influenced by social structure, health beliefs, and various enabling factors. “Potential” access to care depends on the presence of enabling resources, such as the availability of health providers and health care facilities, along with income, health insurance, and a regular source of care. More enabling resources increase the likelihood that services will be available and that utilization will take place. “Equitable” access to care is present when the variance in care among different groups is due to differences in age, gender, or the patient’s perceived need for services. On the other hand, “inequitable access” to care is present when social structure (e.g., race/ethnicity), health beliefs, and enabling resources (e.g., income and insurance) are responsible for the variance in utilization of health care.

The notion of “inequitable access” and the discretionary nature of dentistry provide valuable information regarding the source of the variance in dental care utilization. Consideration of the impact of culture, ethnicity, income, and health insurance, in determining both need and access to dental care, aids in explaining oral health disparities and targeting interventions. Information about the “usual source of care” may be another critical element of health promotion policy. A recent finding has identified that the existence of a “usual source” of medical care is highly predictive of optimal health status and dental utilization.15 Additionally, data regarding specific characteristics of such “usual care” may provide insight into improving utilization of dental care by the underserved.

HEALTH PROMOTION AND ADHERENCE TO CARE

Although the terms compliance and adherence have been used interchangeably in the literature, an important distinction is that adherence is predicated on a mutual agreement by both provider and recipient. This mutuality is deemed essential in effective health communication. Despite medical advancements in reducing disease, adherence is an ongoing, challenging health issue that has received inadequate attention in the education of health professionals.16,17 What is relevant for successful health behavior change in one group may be irrelevant to another group. What does the patient or community know about the condition or targeted behavior? Who needs to be involved in making the decision to change? Health educators recognize that such questions are linked to the success of a treatment or intervention.18,19 To implement treatment or create an oral health intervention for an individual or a community, it is crucial to find common ground between the provider and recipient. Successful treatment or intervention depends on the exchange of ideas, attitudes, and behaviors. The process may call for adopting new behaviors or eliminating risk behaviors. To facilitate behavior change and increase adherence with desired goals, mutual understanding and compromise are essential. Surveys, instruments, personal interviews, and focus groups are methods of acquiring salient information. Multiple sources must be tapped to gather data to sensitize us to the needs of the community. The community represents the stakeholders and partners, the target audience, community health providers, and opinion leaders such as newspaper reporters or editors, politicians or teachers, as well as lay advocates for patients.

MODELS OF HEALTH PROMOTION

In our efforts to improve health status and reduce health disparities, an understanding of established theoretic frameworks that incorporate psychologic and social variables is warranted. Across these theoretic frameworks, it is generally recognized that people do not change health behaviors unless there is a perceived payoff and their behavior can lead to this payoff. The Readiness to Change Model identifies four distinct stages of change associated with acquiring or sustaining health promotion/disease prevention behaviors.20 Although this model is the foundation for numerous health programs, it has not been applied to oral health programs. The stages are (1) precontemplation, in which there has been no thought about performing or changing a target behavior; (2) contemplation, which represents the phase when consideration of performing or changing behaviors takes place; (3) action, in which the target behavior is adopted; and (4) maintenance, in which the behaviors continue to prevail. Relapse, a regression to any earlier stage, is a recognized part of the model.

As with many intervention programs, baseline assessment of the community or individual is critical to knowing how to best create the program and maintain the targeted behavior. Although the Readiness to Change framework has not been applied to dental behaviors, it offers a promising model for oral health promotion. In the case of the parent or caregiver who has low oral health knowledge about the implications of using a baby bottle with milk at night, the initial program might include an informational exchange before contemplation of behavior change is sought. Fostering behavior through motivational techniques is appropriate during the action and maintenance stages. For example, a scale was recently developed to assess Readiness to Change parenting behaviors associated with risk behaviors of early childhood caries.21

The Health Belief Model emphasizes that behaviors such as visiting the dentist or toothbrushing and flossing are dependent on the individual’s cognitions.22,23 Perceived susceptibility to and the severity of a particular condition are integral to the model. Further, the individual’s perception of the benefits of and barriers to (e.g., costs) following a particular health-related action are also part of the model. In short, those health behaviors that are believed to have many benefits and few barriers are more likely to be followed.24,25 After the completion of considerable research, this model has failed to conclusively explain or predict behaviors based merely on oral health beliefs.26,27 However, this model has formed a foundation for subsequent models and is associated with specific health behaviors.

The Extended Parallel Process Model is a fear appeal theory that is linked to the Health Belief Model.28 This model proposes that when people perceive a health threat they either control the actual health threat (danger) or control their fear about the danger. They weigh their risk of the health threat (e.g., oral cancer) against actions that they can take that would reduce their risk (e.g., stop smoking). Thus the important variables in this model are the perceived threat, perceived susceptibility, and perceived self-efficacy. A variation of this model has been, in part, adapted in dentistry by examining both motivational variables and a vulnerability dimension.29

Social Cognitive Theory postulates the belief that the extent to which one can exert control over one’s behavior and health constitutes the driving force of whether persons are willing to engage in behavior change.30 This theory of behavior change incorporates self-efficacy (cognitive factors) and the social environment (e.g., social support). For example, asking parents whether they believe they can control whether their infants’ teeth will decay is viewed as critical in predicting whether parents will engage in health promotion efforts to reduce early childhood caries. This model has been used in health programs aimed at reducing periodontal disease and increasing oral health maintenance in adults.31,32

Behavioral analytic theories rely on learning theory approaches—using rewards and reinforcements.33 The ABC approach examines antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. The antecedents (A) include enabling factors such as the knowledge and skills needed to carry out the targeted behavioral outcome; behaviors (B) represent the sequential steps needed to achieve the outcome and are the natural consequences (C) of learning. This model has not been implemented much in the Western world but has been demonstrably useful in creating behavior adherence in developing areas. In essence, it is a learning theory approach in which barriers are identified and facilitators are implemented—with particular emphasis on skill acquisition and self-efficacy.

Another approach to understanding the delivery of health care services, as previously alluded to, is Andersen’s revised Behavioral Model of Health Services Use.14 In it, he posits that people’s use of health services is a function of their predisposition to use services, their need for care, and factors that enable or impede use. Predisposing characteristics or need include demographic factors such as age and gender. Personal variables such as education level, occupation, and ethnicity; coping style and command of resources to deal with problems; and the health of the physical environment are all factors that ultimately affect the utilization of health services. These features, in addition to beliefs about health and health services, are proposed to influence perceptions of need and use of such services. This model of health services includes two important additions: (1) the health care system, which incorporates the relevance of health policy and the organization of the health care system as a factor of utilization; and (2) health outcomes, which include perceived health status and consumer satisfaction. These additions allow for a more complex dynamic model containing feedback loops revealing that health outcomes influence predisposing factors, perceived need, and therefore future health behaviors.

FACILITATORS AND BARRIERS TO CARE

The health delivery system influences oral health attitudes and behaviors.34,35 The implementation of facilitators in the system may be as important as the elimination or reduction of barriers to care in changing attitudes and behaviors and improving adherence to treatment regimens. If people feel that dentistry is painful and costly, a campaign to alter these perceptions is important. If the dental clinic is viewed as an unwelcoming facility (e.g., child-unfriendly, rude staff, crowded waiting area, unclean), the system will need to understand the expectations and the cultural and health needs and concerns of the community. Efforts to unravel barriers and increase facilitators are laudable, can be costly, and also require the recognition that system change is needed. Noteworthy facilitators for underserved populations in cross-cultural settings include translators or bilingual staff, flexible appointment times, transportation service, reminder phone calls, and child care services.36–39 Additionally, reducing costs, using sliding pay scales, or affiliating with or enrolling patients into subsidized programs can facilitate access to care. For example, Ryan White funds compensate clinics providing dental care, and funds from social services departments for transportation facilitate access to care for people with limited financial or physical resources. Such funds have increased attendance at clinics and the routine provision of dental care, including anticipatory guidance.37 It is important to note that health status assessments are deemed necessary to evaluate health interventions, as well as to address policy-relevant issues such as effectiveness.

Recognizing the World Health Organization’s definition of health (1958) as “more than the absence of disease” and the identification of sociodental indicators, the development of assessments measuring variations in oral health that can supplement biologically based measures has received increasing attention.38 Over the past two decades, the development of such assessments for older adults has been accomplished, and currently oral health—related quality-of-life assessments for children are being developed.39,40 Data from such assessments are valid health indicators or outcomes only if they are sensitive to multicultural populations.

CULTURAL INFLUENCES ON ORAL HEALTH BELIEFS AND PRACTICES

The significance of culture for health is well recognized in that conceptions and expressions of health are culturally determined and vary both between and within cultural groups.34,41–44 Although measures of disease seemingly have no cultural content, measures of health and quality of life address inherently cultural phenomena. Culture is a complex matrix of interacting elements that is ubiquitous, multidimensional, and complex. It represents knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, meanings, and attitudes, as well as concepts of religion and notions of time, roles, and the universe. In essence, culture is the lens through which we view the world. Johnson42 defines culture as “learned and shared ways of interpreting the world” that thereby provide individuals with ideas about what is relevant or irrelevant, valued or devalued in life. Thus health is “culture bound,” and those interacting cross-culturally can easily become prey to ethnocentrism, in which a health provider or investigator assumes that the values important to the culture in which she or he has been socialized are necessarily shared by all. In health care, communication is complex, requiring careful consideration of cultural concepts of health, illness, and health values and behaviors. Table 5-2 provides examples of specific health-related factors that affect the delivery of dental and health care by ethnicity.45 It should be noted that the group descriptions are generalizations about ethnic groups with the understanding that there is much diversity within groups. Although the groups in the table are not exhaustive, they are representative of those ethnic groups that are most prevalent in the United States.

Understanding Cultural Backgrounds

If a public health practitioner is to understand why a patient engages in risk behaviors associated with his or her oral health status, the practitioner needs to understand the patient’s cultural background. Without this understanding, miscommunication occurs and can lead to adverse health outcomes. Barker46 has identified distinct categories where miscommunication occurs in health-related issues as a result of differences in definitions of verbal and nonverbal messages. The first area, ethnomedical systems, deals with unique cultural beliefs and knowledge about health and disease held by the cultural group. Specific groups believe in personalistic medical systems in which spirits or sorcerers cause disease (e.g., indigenous people of Central and South America); while others believe in the naturalistic medical system wherein health is associated with a balance or equilibrium in the body (e.g., traditional Chinese medicine). For this reason, an individual adhering to a “hot-cold” balance thinks of some conditions, such as a tooth inflammation, as a hot condition brought on by consumption of too many hot foods. Treatment for conditions such as a jaw or joint problem (cold condition) involves consuming hot foods or medicine. An oral cleft may be perceived as the result of “bad” acts by the mother (e.g., infidelity), the evil eye, or the happenstance whereby a pregnant mother looked at a rabbit during pregnancy.47–49 In any case, Western medicine generally treats the health condition based on the physical and medical data (radiographs, laboratory tests, and physical examination) with little consideration of the patient’s perceptions and beliefs. We tend to consider the mind and body as though they are separate entities. The mind-body connection is intrinsically linked to some cultural health values and the connection of the mind-body and the universe. These linkages can be observed in variations among Native American, African, and Chinese health systems.

Ethnocultural Identity

Vast intragroup diversity is associated with ethnocultural identity. Ethnocultural identity refers to the extent to which an individual endorses and practices a way of life associated with a particular cultural tradition.50 It includes multiple behaviors and values. Ethnocultural identity refers only to one’s identity with one’s chosen group(s), whereas acculturation typically refers to the degree to which an individual identifies with or adjusts to mainstream cultures.51 Ethnocultural identity is dynamic and is affected by the acculturation process./>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses