Developmental Disorders

After studying this chapter, the student will be able to:

1. Define each of the words in the vocabulary list for this chapter.

2. Define inherited disorders.

3. Recognize developmental disorders of the dentition.

4. Describe the embryonic development of the face, oral cavity, and teeth.

5. Define each of the developmental anomalies discussed in this chapter.

6. Identify (clinically, radiographically, or both) the developmental anomalies discussed in this chapter.

7. Distinguish between intraosseous cysts and extraosseous cysts.

8. Describe the differences between odontogenic and nonodontogenic cysts.

9. Name four odontogenic cysts that are intraosseous.

10. Name two odontogenic cysts that are extraosseous.

11. Name four nonodontogenic cysts that are intraosseous.

12. Name four nonodontogenic cysts that are found in the soft tissues of the head, neck, and oral region.

13. List and define three anomalies that affect the number of teeth.

14. List and define two anomalies that affect the size of teeth.

15. List and define five anomalies that affect the shape of teeth.

16. Define and identify each of the following anomalies affecting tooth eruption: impacted teeth, embedded teeth, and ankylosed teeth.

17. Identify the diagnostic process that contributes most significantly to the final diagnosis of each developmental anomaly discussed in this chapter.

Inherited disorders are different from developmental disorders in that they are caused by an abnormality in the genetic makeup (genes and chromosomes) of an individual and transmitted from parent to offspring through the egg or sperm. Inherited disorders are discussed in Chapter 6.

Embryonic Development of the Face, Oral Cavity, and Teeth

Face

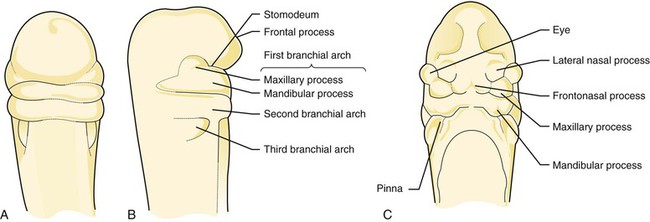

Development of the face is a process of selective growth or proliferation and differentiation (Figures 5-1 and 5-2). During the third week of embryonic life, an invagination, or infolding, of the ectoderm forms the primitive oral cavity, which is called the stomodeum. Just above the stomodeum is a process called the frontal process, and just below it is a structure called the first branchial arch. Additional branchial arches form below the first branchial arch. All of the face and most of the structures of the oral cavity develop from either the frontal process or the first branchial arch. The first branchial arch divides into two maxillary processes and the mandibular process. The maxillary processes give rise to the upper part of the cheeks, the lateral portions of the upper lip, and part of the palate. The mandibular arch forms the lower part of the cheeks, the mandible, and part of the tongue.

Oral and Nasal Cavities

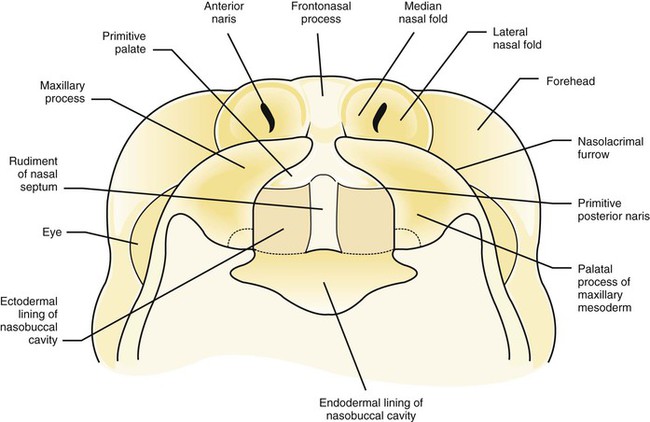

The area of the palate called the premaxilla develops from the globular process. The lateral palatine processes (left and right) are formed from the maxillary processes. These lateral palatine processes then fuse with the premaxilla. The fusion creates a Y-shaped pattern (see Figure 5-2). The nasal septum arises from the median nasal process. The right and left maxillary processes fuse together with the nasal septum at the center of the palate.

The tongue develops from the first three branchial arches. The second and third branchial arches are located just below the first branchial arch (Figure 5-1, B). The body of the tongue forms from the first branchial arch, and the base of the tongue forms from the second and third branchial arches.

Teeth

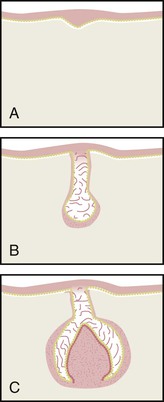

Odontogenesis begins with the formation of a band of ectoderm in each jaw called the primary dental lamina. Ten small knoblike proliferations of epithelial cells develop on the primary dental lamina in each jaw (Figure 5-3, A). Each of these proliferations extends into the underlying mesenchyme, becoming the early enamel organ for each of the primary teeth (Figure 5-3, B).

The tooth germ is composed of three parts: (1) the enamel organ, (2) the dental papilla, and (3) the dental sac, or follicle (Figure 5-3, C). The enamel organ develops from ectoderm, and the dental papilla and dental sac or follicle develop from mesoderm. Cell differentiation in the enamel organ progresses to produce ameloblasts, which form enamel. In the dental papilla odontoblasts are produced to form dentin. The permanent, or succedaneous, enamel organs form at the same time.

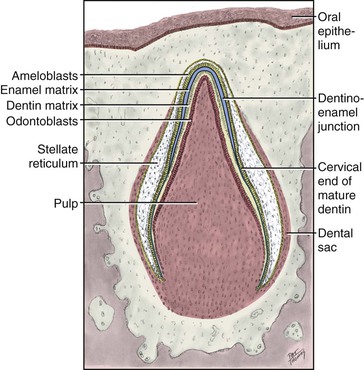

Formation of dental hard tissues occurs during the fifth month of gestation (Figure 5-4). Dentinogenesis is the formation of dentin. Dentin is the first mineralized tooth tissue to appear. When it begins to form, the mesenchymal tissue within the tooth germ is called the dental papilla. After dentin is produced, the dental papilla is called the dental pulp. Enamel is the product of the enamel organ. Enamel matrix begins to form shortly after dentin, and mineralization and maturation of enamel follow the formation of the matrix. Amelogenesis refers to the formation of enamel. The enamel is highly mineralized epithelial tissue and 90% of its volume is occupied by hydroxyapatite crystals.

Developmental Soft Tissue Abnormalities

Ankyloglossia

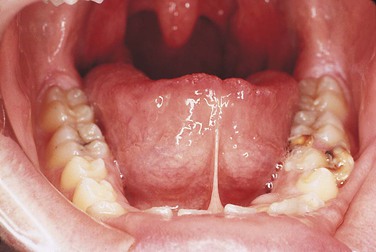

Ankyloglossia is a developmental anomaly of the tongue. It is an extensive adhesion of the tongue to the floor of the mouth, caused by a short lingual frenum. The condition is often referred to as “tongue-tied.” Ankyloglossia is derived from the Greek words ankylos, meaning adhesion, and glossa, meaning tongue. This adhesion results from the complete or partial fusion of the lingual frenum to the floor of the mouth. It is four times more common in boys than girls. Total ankyloglossia is rare. Partial ankyloglossia appears clinically as a very short lingual frenum connecting the anteroventral portion of the tongue to the floor of the mouth (Figure 5-5). Patients with a short lingual frenum may exhibit no adverse effects, but some may have problems with speech. Gingival recession and bone loss can occur if the frenum is attached high on the lingual alveolar ridge. Surgical removal of a portion of the lingual frenum, known as frenectomy, is the usual treatment for ankyloglossia.

Commissural Lip Pits

Commissural lip pits are epithelium-lined blind tracts located at the corners of the mouth (commissures) (Figure 5-6). These tracts may be shallow, or they may be several millimeters deep. They are a relatively common developmental anomaly. The cause of commissural lip pits is not clear; both the incomplete fusion of the maxillary and mandibular processes and the defective development of the horizontal facial cleft have been suggested. They are more often seen in adult males. The commissural lip pit may be observed during examination.

Developmental Cysts

The most common cyst observed in the oral cavity is caused by pulpal inflammation and is called a radicular cyst (periapical cyst). This cyst is described in Chapter 2. It develops from a preexisting periapical granuloma found at the apex of a nonvital tooth. The radicular cyst is always associated with a nonvital tooth and diagnosis can be made only through microscopic examination because the radiographic appearance can be similar to other lesions. A residual cyst is a radicular cyst that remains after extraction of the offending tooth. Because cysts are commonly observed in the jaws and surrounding soft tissues, the dental hygienist should understand their diagnostic criteria, pathogenesis, and prognosis. The preliminary identification of a cystic lesion is within the scope of dental hygiene practice.

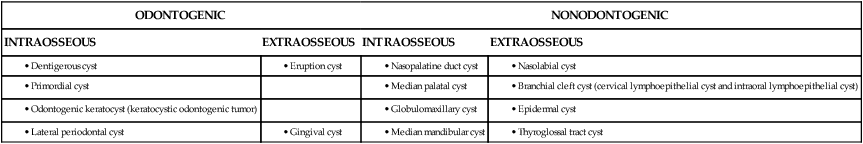

Developmental cysts are classified as odontogenic (related to tooth development) and nonodontogenic (not related to tooth development). Cysts are also classified according to location, cause, origin of the epithelial cells, and microscopic appearance (Table 5-1). Developmental cysts can vary in size from small, asymptomatic lesions to large lesions that can cause expansion of bone. Very large and long-standing lesions can resorb tooth structure or move teeth. Oral cysts that occur within bone are called intraosseous cysts, and cysts that occur in soft tissue are called extraosseous cysts.

TABLE 5-1

Classification of Developmental Cysts

| ODONTOGENIC | NONODONTOGENIC | ||

| INTRAOSSEOUS | EXTRAOSSEOUS | INTRAOSSEOUS | EXTRAOSSEOUS |

Odontogenic Cysts

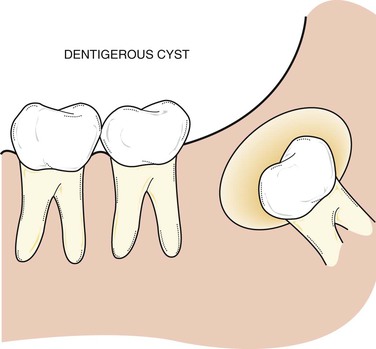

Dentigerous Cyst

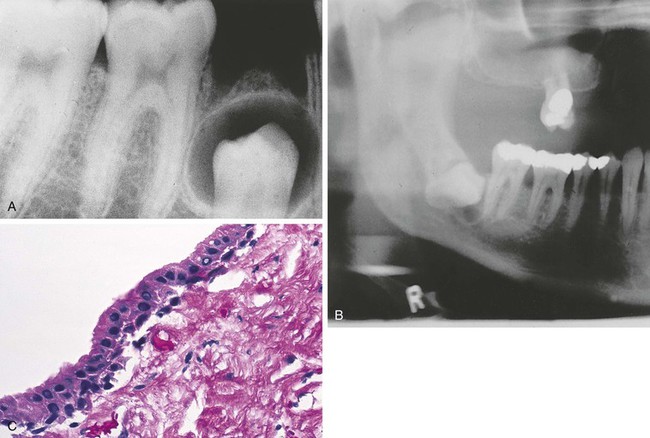

A dentigerous cyst, also called a follicular cyst, forms around the crown of an unerupted or developing tooth (Figure 5-7). It is the second most common odontogenic cyst after the radicular cyst. The epithelial lining originates from the reduced enamel epithelium after the crown has completely formed and calcified. Fluid accumulates between the crown and the reduced enamel epithelium. The reduced enamel epithelium results from remnants of the enamel organ. The most common location for the dentigerous cyst is around the crown of an unerupted or impacted mandibular third molar. However, a dentigerous cyst may form around the crowns of other unerupted or impacted teeth such as the maxillary cuspid or a supernumerary tooth. The cyst may develop in both males and females. However, there is a higher incidence in males and this cyst is most often seen in young adults in their twenties and thirties. The size of these cysts can range from small and asymptomatic to very large. When large, it is capable of displacing teeth or causing a fracture of the mandible.

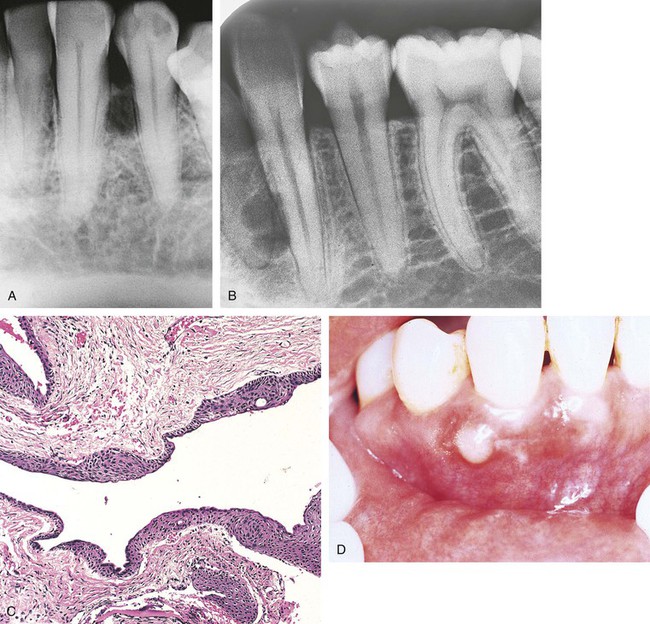

Radiographically, the dentigerous cyst appears as a well-defined, unilocular radiolucency around the crown of an unerupted or impacted tooth (Figure 5-8, A and B). Microscopically, the lumen is most characteristically lined with cuboidal epithelium surrounded by a wall of connective tissue (Figure 5-8, C). It may also be lined with stratified squamous epithelium. The lumen may be filled with a watery or serous fluid.

Treatment of a dentigerous cyst involves the complete removal of the cystic lesion and usually the tooth involved. If it is not removed, the cyst wall continues to enlarge. In addition, a risk exists that a neoplasm (i.e., ameloblastoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma) may develop (see Chapter 7).

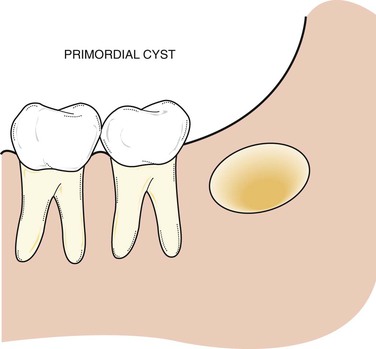

Primordial Cyst

A primordial cyst develops in place of a tooth and is most commonly found in place of the third molar or posterior to an erupted third molar (Figure 5-9). It originates from remnants and degeneration of the enamel organ. A history that the tooth was never present is an essential component of the diagnostic process.

Odontogenic Keratocyst (Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor)

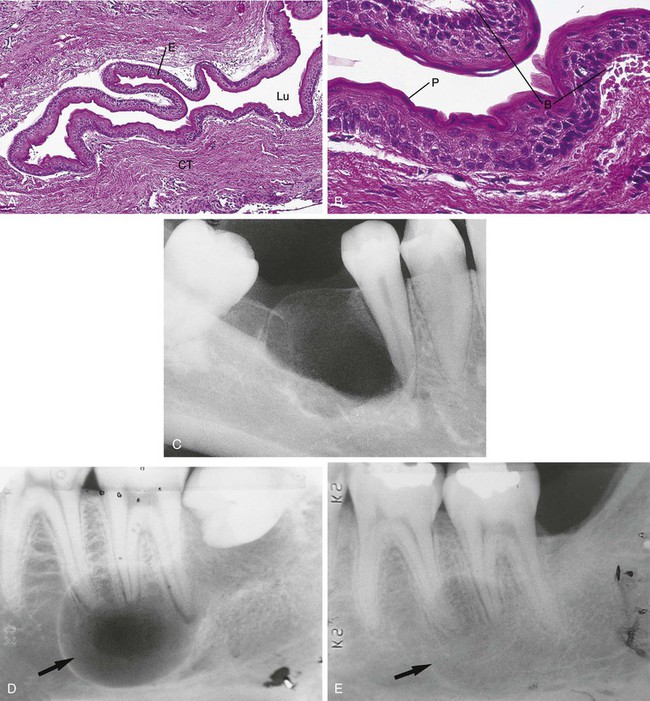

An odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) is an odontogenic developmental cyst that is characterized by its unique microscopic appearance and frequent recurrence. The lumen is lined by epithelium that is 8 to 10 cell layers thick and surfaced by parakeratin. The basal cell layer is palisaded and prominent; the interface between the epithelium and the connective tissue is flat (Figure 5-10).

These cysts are most often seen in the mandibular third-molar region, and there is a slight predilection for males. Radiographically, the odontogenic keratocyst frequently appears as a well-defined, multilocular, radiolucent lesion (Figure 5-10, C). Unilocular lesions may also occur. The radiographic appearance of an odontogenic keratocyst can be identical to that of an odontogenic tumor. The odontogenic keratocyst can move teeth and resorb tooth structure but does not usually cause expansion of bone. The odontogenic keratocyst is also associated with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome) (see Chapter 6).

Treatment of an odontogenic keratocyst is rather aggressive because of the high recurrence rate (Figure 5-10, D and E). The cyst generally extends beyond the borders that are seen on the radiograph because it extends between the trabeculae of bone. Therefore thorough surgical excision and osseous curettage are recommended. Careful follow-up and evaluation are essential.

Calcifying Odontogenic Cyst

The calcifying odontogenic cyst is a developmental nonaggressive cystic lesion lined by odontogenic epithelium that closely resembles the epithelium of the odontogenic tumor called an ameloblastoma; in addition, microscopically, it has a characteristic feature called ghost cells. In general, the cyst is treated conservatively and does not recur. A solid variant of the calcifying odontogenic cyst is called the odontogenic ghost cell tumor; it has been suggested that this solid variant represents a neoplasm rather than a cyst. Because of its microscopic resemblance to the ameloblastoma, the calcifying odontogenic cyst is described in detail in Chapter 7.

Lateral Periodontal Cyst, Gingival Cyst, and Botryoid Odontogenic Cyst

The lateral periodontal cyst is named for its location. It is seen most often in the mandibular cuspid and premolar area. It presents as an asymptomatic, unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesion located on the lateral aspect of a tooth root (Figure 5-11, A). When multilocular, it is known as a botryoid cyst (Figure 5-11, B). Microscopically, the lateral periodontal cyst and the botryoid cyst show a thin epithelial lining with focal epithelial thickenings. The gingival cyst exhibits the same type of epithelial lining as the lateral periodontal cyst and is located in the soft tissue of the same area. The gingival cyst appears as a small bulge or swelling of the attached gingiva or interdental papillae (Figure 5-11, C).

Nonodontogenic Cysts

Nasopalatine Canal Cyst

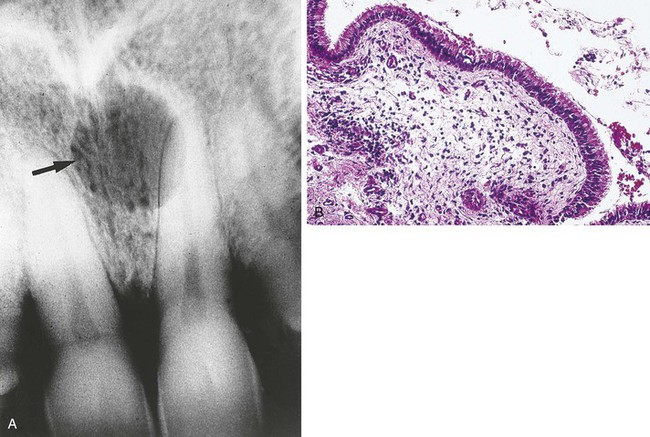

Radiographically, the nasopalatine canal cyst is a well-defined, radiolucent lesion that is often heart shaped (Figure 5-12, A), resulting from the anatomic Y shape of the canal. When it is heart shaped, it is evenly distributed to the right and left of the midline.

Microscopically, the cyst is lined by epithelium that varies from stratified squamous to pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (Figure 5-12, B). The connective tissue wall contains nerves and blood vessels that are normally found in the area and may also contain inflammatory cells.

Median Palatine Cyst

A median palatine cyst appears as a well-defined unilocular radiolucency and is located in the midline of the hard palate (Figure 5-13). The cyst is thought to be a more posterior form of a nasopalatine canal cyst. Microscopically, the median palatine cyst is lined with stratified squamous epithelium that is surrounded by dense fibrous connective tissue. The median palatine cyst is treated by surgical enucleation. The prognosis is good, and recurrence is rare.

Globulomaxillary Cyst

Radiographically, a globulomaxillary cyst is a well-defined, pear-shaped radiolucency found between the roots of the maxillary lateral incisor and cuspid (Figure 5-14). Although it was once thought to be a developmental fissural cyst, it is now believed to be of odontogenic epithelial origin. The size of the lesion can vary; however, when it is large enough, a divergence of the roots can result. The adjacent teeth are usually vital. Pulp testing can rule out a periapical cyst or periapical granuloma. Surgical enucleation of the globulomaxillary cyst is recommended. The diagnosis is determined by the microscopic evaluation of the lesion. The prognosis and recurrence depend on the final diagnosis.

Nasolabial Cyst

Clinically, there may be an expansion or swelling in the mucolabial fold in the area of the maxillary canine and the floor of the nose. Usually no radiographic change is associated with this cyst. However, when the lesion is large enough, expansive pressure can cause the resorption of bone (Figure 5-15). Microscopically, the cyst is lined with pseudostratified, ciliated columnar epithelium and multiple goblet cells. Treatment of a nasolabial cyst is surgical excision; the prognosis is good, and recurrence is rare.

Lymphoepithelial Cyst

A cervical lymphoepithelial cyst (branchial cleft cyst) is located on the lateral neck at the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It is composed of a stratified squamous epithelial lining surrounded by a well-circumscribed component of lymphoid tissue and connective tissue (Figure 5-16, B). It appears to arise from epithelium entrapped in a lymph node during development rather than associated with a branchial cleft.

The intraoral lymphoepithelial cyst is most commonly seen on the floor of the mouth and the lateral borders of the posterior tongue (Figure 5-16, A). This lymphoepithelial cyst appears as a pinkish-yellow, raised nodule when seen intraorally.

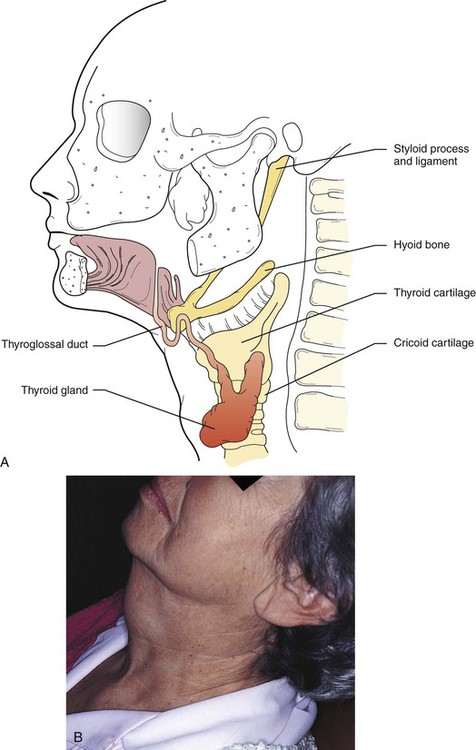

Thyroglossal Tract Cyst

A thyroglossal tract (duct) cyst forms along the same tract that the thyroid gland follows in development, from the area of the foramen cecum to its permanent location in the neck (Figure 5-17). Most of these cysts occur below the hyoid bone. The epithelial lining varies with location. Cysts above the hyoid bone are usually lined with stratified squamous epithelium, and those below the hyoid bone with ciliated columnar epithelium. Thyroid tissue may also be found within the connective tissue wall.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)