4

Psychosocial Factors in Motivation, Treatment, Compliance, and Satisfaction with Orthodontic Care

Summary

This chapter describes what is known by social scientists and epidemiologists about why and when individuals seek orthodontic care; the cognitive, affective, and behavioral factors involved in becoming an orthodontic patient; and behaviors appropriate during treatment and subsequent compliance. The authors present some of their own work on using a range of acceptability rather than a static image between patient and clinician to communicate about what is in a patient’s mind or the perception of changes in facial morphology to achieve a satisfactory treatment outcome. The influence of ethno-cultural differences, effective communication, and health literacy are discussed. Finally, recommendations are offered for managing psychosocial problems when the process and outcome do not progress as planned for patients, parents, and clinicians.

Introduction

Not too long ago, orthodontists, of all the dental specialties, had to deal with the most complex psychosocial issues because most orthodontic patients were children and adolescents who were working out conflicts with authority figures such as parents and teachers as well as the orthodontist, who like other doctors, were perceived to be in charge (Miller and Larson, 1979). Parents, usually the mother, also had to interact with their children and the clinician in making decisions about orthodontic treatment. Orthodontists actually shared the burden with parents for motivating their children to comply with the requirements of orthodontic treatment. Modern orthodontics, however, has progressed beyond ‘beware of children’ to interacting, complementing, and even competing with other dental and medical specialists involved in the increasing complexities of overall health care.

Motivation for Orthodontic Care

Relationship of the Morphology and Function of the Orofacial Area to Quality of Life

Although not everyone agrees that orthodontic treatment improves physical and mental health as part of overall quality of life (Kenealy et al., 2007), few doubt that the orofacial-cranial area is the most important part of the body, the rest being a support system. Following from Maslow’s (1943, 1970) hierarchy of needs and more recent revisions (Kenrick et al., 2010), the orofacial area is essential for survival as the portal for food and water, as well as security or defense; then for communication using the lips, tongue, teeth, and muscles of facial expressions for verbal and nonverbal communication. After meeting these basic biosocial needs, the orofacial area is available for satisfying higher-order hedonic, esthetic, gustatory, sensual, and intellectual activities (Giddon, 1999; Jones, 2009).

While the eyes may be the window to the soul, the mouth is also a window to the body’s physical and mental health (Giddon, 1999). The genetically determined, ontological sequence further supports the intimate relationship of the intraoral structures to the developing brain, face, and cranial soft and hard tissues as does the disproportionate neuroanatomical and physiological representation of the orofacial area in the sensory and motor homunculi, including the muscles of mastication and facial expression (Penfield and Rasmussen, 1978). Thus there is all the more reason for preserving the structure and function of the muscles of facial expression, which ‘constitute the most highly differentiated and versatile set of neuromuscular mechanisms in man’ (Izard, 1971). Recent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have also documented activation of specific areas of the brain in response to noxious stimulation of the orofacial area (Kitada et al., 2010). A related earlier observation is the apparent need for some periodic oral activity, such as speaking, eating, drinking, chewing gum, smoking, smiling, kissing, yawning, laughing, frowning, and clenching on average every 96 minutes (Friedman and Fisher, 1967).

Given that the major motivation for orthodontic treatment is to improve physical appearance as a means to enhance social acceptance and quality of life (Baldwin, 1980; Giddon and Anderson, 2006), the orthodontist and referring dentist should discuss any concerns about the teeth and surrounding orofacial area in relation to body image, self-concept, and quality of life before deciding if and when to begin orthodontic treatment. Possible loss of teeth or orofacial mutilation can also be a concern, whether from trauma, multiple extractions, or orthognathic surgery (Giddon, 1999). As Cervantes notes through Don Quixote, ‘I had rather they had tore off an arm, provided it were not the sword arm; for, Sancho, you must know, that a mouth without grinders is like a mill without & [sic] stone; and a diamond is not so precious as a tooth’ (Cervantes).

For children, a loose tooth is an exciting event. The child continues to pull at it until the primary tooth loosens up and falls into their hands. The child then slips it under the pillow with anticipation that the tooth fairy is on the way to replace the tooth with money while they are sleeping. Thoughts or dreams of losing teeth, having teeth crumble, rot or grow crooked are frequently reported. Fear of losing teeth in dental patients due to biomechanical tooth movement or gingival recession may have a major impact on patients’ perceptions of their appearance and quality of life because people cannot change the appearance of missing teeth. According to Freud, Jung, and others (Lorand and Feldman, 1955), thoughts of losing teeth may be symbolic of loss of power or fear that some permanent part of a person’s life is about to change or is under threat. The fear of loss of teeth may also represent a retreat to infancy (i.e., when, toothless, the mother was the source of nourishment and comfort), and hence a refusal to face reality. Fears of tooth loss have also been theorized to be important symbols of fear of castration, sexual repression, or masturbatory desires during puberty. Jung (2010) attributed fear of losing teeth in woman to parturition.

Example of Patient with Underlying ‘Tooth Fairy’ Issues

Patient LF, being treated by an orthodontist after a fall, displaced her maxillary incisors palatally.

- The teeth were realigned but the patient became very anxious at thought of debonding.

- The orthodontist removed the archwires several months before debonding

- They then sent LF back to the prosthodontist for reassurance that teeth would be healthy enough to continue treatment.

Suggestions

- Acknowledge patient’s fears about the fall and the importance of the teeth for survival, social interactions, and physical appearance.

- Provide resources to look up the work of Freud, Jung, and others about the symbolism of teeth.

- Urge patient to ‘test’ his or her tooth strength by eating foods which require biting or tearing, such as dried meats, apples, chewing gum.

- Proceed slowly as above by removing wires, then debonding.

- Arrange for ways that the patient can receive appropriate attention.

Need Versus Demand for Orthodontic Care

Objective measures of malocclusion or need for orthodontic treatment does not translate directly into perceived demand, which may or may not result in actual care. Nevertheless, the demand for orthodontic treatment continues to increase for both children and adults. The American Association of Orthodontists reports a 37% increase from 1994 to 2004 in the number of adult patients in the United States (Bick, 2007). It is estimated that, with cost barriers removed, 60% of the population would be interested in receiving orthodontic care (King, n.d.), and that 77% of Americans agree that straightening ‘crooked teeth’ is one of the best investments a person can make in improving his or her appearance (Anon, 2005). While the relative shortage of orthodontists explains some of the discrepancy between need and demand, psychosocial and economic variables provide the most likely explanation of the discrepancy. In other words, the difference between demands or the desire to seek orthodontic treatment and actually receiving it is a function of acceptability based on the willingness to comply with temporal and financial requirements of a successful outcome.

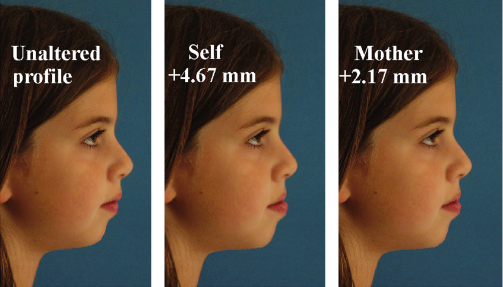

Based on oral health-related quality of life measures, differences in emotional and social wellbeing were found between children with malocclusions and acceptable occlusions, even though there were no differences in oral function (Kiyak, 2008). Perceived benefits also differ between referring dentists and orthodontists. In Northern Ireland, both groups agreed on the top five benefits as physical attractiveness, self-esteem and self-confidence, less teasing, and easier-to-clean teeth. As expected, general dentists saw greater benefits for oral function and health than the specialists’ and patients’ perception of the psychosocial benefits of orthodontic treatment (Kiyak, 2008). Thus, what the clinician thinks is best for the patient is not necessarily what the patient and/or parent wants. Note, for example, Miner et al. (2007), who found differences among the perceived preferences of patients, parents, and clinicians, as shown in Figure 4.1. In addition to the assumed skill of the clinician, the actual and perceived behaviors of the orthodontist and staff, including physical appearance, are major factors (Urban et al., 2009), for example, politeness, providing accurate information to enhance health literacy, reassurance, etc. Such demonstration of concern is significantly correlated with compliance and ultimately patient satisfaction (Sinha et al., 1996).

Figure 4.1 Results for most accurate task displaying least accurate patient/mother.

(Source: Miner et al., 2007; courtesy of The EH Angle Education and Research Foundation.)

Cognitions, Emotions, and Behavior Influencing Motivation for Orthodontic Treatment

The psychosocial variables intervening between need and demand for treatment can be conceptualized into three domains: cognition, which includes memories and perceptions or what we think about verbal or nonverbal communications between patients and clinicians, the accuracy of which is as noted in the next section ‘Communication and health literacy’. The affective domain includes emotion and associated neurophysiological responses, including facial expression, or how we feel about the communication. Emotions also provide cues to intended behaviors regarding whether or not to seek treatment. Attitudes then denote the directionality and magnitude of feeling about the transferred information. Beliefs reflect the influence of age, gender, ethno-cultural and socioeconomic variables determining personal values indicating why we feel the way we do about changes in the facial morphology. Emotions certainly enter into a child’s decision to accept treatment because of being teased or bullied related to his or her Class II malocclusion, or reject treatment because braces make him or her look different. Of course, the negative emotional state may be overcome by a promised trip to Disney World.

The behavioral domain has three clinically distinct categories: volitional, semi-volitional, and nonvolitional. Volitional behaviors refer to an individual’s intended actions mediated by the somatic nervous system, e.g. for speech, preventive oral health, keeping appointments; or conversely, noncompliant actions such as not wearing headgear or elastics, making inappropriate verbal comments, or unreasonable demands such as debonding before an important social event. Also mediated by the somatic nervous system are the semi-volitional behaviors, such as breathing, facial expressions, and most pernicious habits, such as tongue thrusting, nail biting, clenching, smoking, and gum chewing or gagging. Nonvolitional behaviors are primarily under the control of the autonomic nervous and neurohormonal system, of which the patient is not usually aware, such as changes in salivary flow, diaphoretic activity on the upper lip and ventral surface of the hand, pupillary dilation, palpitations, and other responses associated with anxiety, depression, or discomfort related to mechanical tooth movement (Giddon et al., 2007).

Each individual in fact has a unique and consistent pattern of responses across different stressors (Sternbach, 1966; Bakal, 1992; Belsky and Pluess, 2009). The magnitude and duration of these responses may vary on a continuum from simple annoyance to severely disruptive psychopathology. Of relevance to orthodontists is the demonstration of greater psychophysiological responses to simulated distortion of one’s own profile than found with distortion of a neutral profile (Amram et al., 1998).

Communication and Health Literacy

The first step in motivating patients to participate in orthodontic treatment should be to facilitate effective communication among patients, surrogates, and clinicians about the importance of morphology and function of the orofacial area to overall physical and mental health (Colgate, 2006; Jontell and Glick, 2009); the second step is to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of orthodontic treatment. Specifically, does the patient understand the importance of a realistic treatment and is the patient willing to do what is necessary to comply with treatment protocols.

Health literacy is defined as ‘the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions’ (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Deficiencies in health literacy are now a concern of all healthcare professionals (Anderson and Giddon, 2010). Poor health literacy is estimated to affect 90 million Americans (Nielsen-Bohlman and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy, 2004) and costs the healthcare system US$73 billion annually (in 1998 dollars) (National Academy on an Aging Society, 2009). Poor health literacy is a better predictor of poor health status than age, income, employment, education level, or race (Kutner et al., 2006).

As orthodontic treatment may be uncomfortable, inconvenient, or costly, patients with low health literacy may not fully comprehend the biological reasons for orthodontic treatment. Such patients also may not appreciate the esthetic and oral health benefits or the importance of keeping appointments. As any orthodontist knows, such behaviors occur among affluent and health-literate patients as well, exemplified in the case of a Class II Division 1, 11-year-old patient, the son of two dentists, who was referred for orthodontic treatment. He resisted doing anything other than appearing for the orthodontic consultation. He could not care less about the likely benefits or compliance. In spite of much cajoling by the orthodontist, he discontinued treatment with apparently no psychosocial consequences of a lifelong Class II malocclusion – he became a very successful ‘buck-toothed’ president of a bank.

As noted by Will (in press), patients do not always understand or remember what they have been told about their malocclusion or the orthodontic treatment plan. After discussing the reasons for the proposed treatment, risks, likely treatment outcome, and responsibilities of patients and clinicians noted in the informed consent form, Mortensen et al. (2003) interviewed children and their parents. Only an average of 1.5 risks out of 4.5 mentioned were recalled by the parents, with less than one by the children. Similarly, of 2.3 reasons for treatment, the parents remembered an average of 1.7 and the children 1.1. Clearly, most of what is important is not remembered by patients or parents.

Perhaps the most critical information to be communicated for a successful treatment outcome is the need for the patient to understand the differences between objective cephalometric data and subjectively determined profile preferences, that is, this distinction is necessary to determine the patient’s self-perception of his or her actual facial configuration relative to what changes are being planned and why; and then how the patient feels about these proposed changes. Unfortunately, many misunderstandings about expected changes become examples of deficiencies in health literacy or rather illiteracy. Even the meaning of words used to describe existing and/or desired changes may differ between patient and clinician. To overcome this problem a simple binary classification is suggested, similar to that used with the quantitative, psychophysical facial perception PERCEPTOMETRICSTM method. Thus, negative words such as ‘ugly’, ‘awful’, ‘grotesque’, or ‘unattractive’ are all classified as ‘unacceptable’, while positive terms such as ‘pretty’, ‘cute’, ‘attractive’, ‘gorgeous’, or ‘beautiful’, or referring to specific features as ‘symmetrical’, ‘protrusive’, etc., are classified as ‘acceptable’ (Giddon, 1995). The same approach can be used to determine the precise anthropometric basis for each one of these negative or positive esthetic descriptors.

What is considered attractive or preferred obviously differs among dental health professionals and lay persons (Prahl-Anderson et al., 1979; Cochrane, et al., 1999). In addition to maximizing cooperation and mutual satisfaction, the use of quantitative methods to establish a range of proposed or preferred changes, rather than a series of single static photo images, will reduce the risk of medicolegal action resulting from unfulfilled expectations which may well have been unrealistic. Thus, it behooves the orthodontist to provide the patient with enough understandable information to agree with an acceptable and realistic expectation of treatment outcome. The treatment process itself can also be the source of disruptive and unnecessary agitation. For example, the problem may simply be due to the failure to explain that biomechanical movement of teeth can cause unpleasantness or pain as the result of unexpected stimulation of tactile or proprioceptive receptors in the periodontal membrane (Giddon et al., 2007). To anticipate problems with patients, it is essential to obtain a detailed medical and social history with a list of medications together with clinical observations and laboratory data as an essential part of effective communication between patient and clinician.

Sensation and Perception

Very simply stated, perception begins with sensation, which is objectively defined as the recognition that the sensory receptors have received input from the internal and external environment. Perception may then be defined as a central nervous system process of providing organization and meaning to the incoming sensory information. The quantitative relation of sensation to perception can then be determined mathematically with psychophysical methods (Giddon, 1995; Treutwein, 1995).

Except for expected universal responses to cataclysmic events, there are large individual differences in perception of sensory input which run the gamut from noxious stimulation to the stressor of being different by virtue of being unattractive (McEwen and Gianaros, 2010).

Physical Basis of Perception of Attractiveness

While beauty is traditionally considered to be in the eyes of the beholder, there is increasing evidence of a specific and almost universally agreed-upon configuration of hard and soft tissues being judged as attractive (Jones and Hill, 1993; Anderson and Giddon, 2005; Giddon et al., 2007). As noted by Giddon (1995) and others, the key to understanding the responses to physical appearance is not the actual morphology but the perception by self and significant others as well as the clinician.

An extensive literature exists on improved facial attractiveness as the most important motivation for obtaining orthodontic treatment; for example, some of the benefits attributed to a more attractive face include the perception by others of greater cognitive ability, intelligence, and social skills. Dion et al. (1972) found that attractive individuals were seen as more successful and as achieving higher socioeconomic status and greater marital happiness than those whose faces were judged as unattractive. Subsequent research (Patzer, 1985; Alley, 1988; Wood and Eagly, 2002) provides a consensus across gender, ethnic, and age groups that what is beautiful is good. Compared with unattractive counterparts, attractive individuals receive better grades, higher salaries, shorter prison sentences, and are considered to be more competent, successful, confident, assertive, and likeable, with better mental/physical health. Individuals with attractive dentitions are viewed as more desirable as friends, intelligent, and less likely to behave aggressively than those with unattractive dentitions (Zhang et al., 2006; Jung, 2010).

Perception of Facial Attractiveness

As noted earlier by Baldwin (1980), approximately 80% of those seeking orthodontic treatment do so for esthetic rather than functional reasons. Potential patients judge their appearance by looking at a reflection of their full face, while the orthodontists base their assessments primarily on the profile, which is not easily viewed by the patient. Hershon and Giddon (1980) pointed out that most people, in fact, have no idea about their own profiles. The fact that perceived personality and other characteristics attributed to the profile differ from those for the full frontal face only adds more complexity and possible shortcomings to the two-dimensional (2D) representations of faces (Bruce et al., 1991; Hancock et al., 2000).

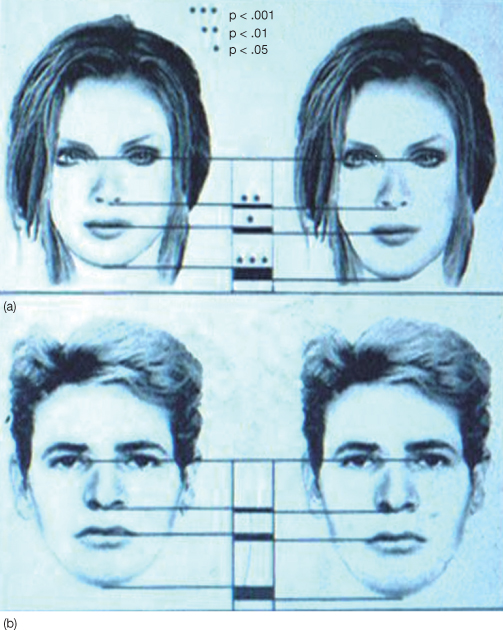

While the orofacial area is more important than the rest of the body in judging overall attractiveness and ultimately self-concept (Currie and Little, 2009), the mouth itself is second only to the eyes in focus of attention (Hassebrauck, 1998). Jornung and Fardal (2007), however, found that patients rated teeth as the most important feature in judging facial attractiveness, with no gender difference (York and Holtzman, 1999). There are many computer methods to derive the ideal face, as shown in Figure 4.2, in which both the male and female faces with shortened lower jaw are considered more attractive than the face with average proportions.

Figure 4.2 Computer-generated female and male faces, one with average proportions (right panels) and one with short lower jaw proportions (left panels).

(Source: Johnston and Oliver-Rodriguez, 1997. Available at: www.informaworld.com. Courtesy of Taylor and Francis.)

Facial perception per se differs from perception in general only in complexity of cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to objective visual, sensory input; for example, gaze aversion or increasing interpersonal distance from people with craniofacial anomalies (Giddon, 1995). The cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to perceived anomalies can often have disproportionately greater impact than the actual magnitude of the disfigurement. Individuals with ‘mild’ dysmorphias as classified by the clinician may be at greater risk for developing psychological problems than those with severe dysmorphias (MacGregor et al., 1953); that is, patients with mild to moderate facial deformities who perceive themselves as near normal may actually experience greater psychological distress than those with more severe anomalies. As shown by Bruun et al. (2008), there is some disagreement even among clinicians about what is classified as mild, moderate, or severe. In general, however, the more severe the deformity, the more consistent and predictable are the negative, often stereotypical, reactions. Such patients may in fact develop a subculture with different methods for coping with social inequities.

The consequences of having more severe craniofacial anomalies such as cleft lip and palate or other relatively severe physical and mental deviations from ‘normal’ can evoke cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to being different, whether because of craniofacial anomalies only, or being challenged intellectually or physically, or because of ethnicity/color, size and shape, etc. Encounters such as bullying, isolation, avoidance, and other antisocial behaviors, can result in physical and verbal abuse, adding even more to the decrement in the quality of life compared with unaffected controls (Collett and Speltz, 2007). Day-to-day interactions with peers can be hindered by a poor self-image and resulting low self-esteem. The self–perception of being physically unattractive thus negatively affects a patient’s mental health (Giddon and Anderson, 2006).

Patients with visible facial disfigurements tend to be judged as less intelligent, and less athletic, with attributes such as untrustworthiness and dishonesty (MacGregor et al., 1953; Stricker et al., 1979). Even parents may view their unilateral cleft lip and palate children (UCLP) negatively, with a greater likelihood of sexual or physical abuse than non-UCLP children (Sullivan et al., 1991). Children with anomalies often have a lower frustration tolerance, resulting in behavior which increases the household stress and the risk of being maltreated by parents or trusted adults such as teachers (Polnay, 1993). One recognized risk for child abuse is early separation from the parents during hospitalization for primary repair of cleft lip/palate (Sullivan et al., 1991). Also, children with UCLP often have behavioral problems with parents and teachers (Collett and Speltz, 2007), which may become internalized with psychophysiological manifestations of stress.

Quantitative Methods for Determining the Anthropometric Bases for Perception of Attractiveness

As noted earlier (Albino et al., 1981; Giddon, 1995), the most important psychosocial variable influencing the decision to seek and comply with orthodontic treatment is the patient’s perception of what he or she prefers to accomplish following treatment; in other words, what is in the patient’s head or the ideational representation, which the clinician can attempt to elicit by conversation but is more likely to be obtained or inferred from the responses to manipulation of quantitative measures of anthropometric data.

Because most people cannot recall or reproduce their own profiles (Hershon and Giddon, 1980), it is first necessary to determine the accuracy of patients’ self-perceptions by comparison with their actual cephalometrically determined data, such as the soft tissue profile, prior to establishing their post-treatment preferred profile. A variety of quantitative methods are now available to assess the physical bases of perceived morphology, many of which use standardized images (e.g. Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN) (Brook and Shaw, 1989). Others use 2D or 3D imaging methods to display anthropometric information for determining the accuracy of the self-perception as well as preferences for post-treatment changes in the soft-tissue profile, e.g. 3DMD, Dolphin Imaging (Sarver, 1993; Berco et al., 2009; Lamichane et al., 2009). Most of these newer techniques, however, still provide a series of static images from which patients can select. In contrast, the ps/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses