Chapter 4

Preventive Measures

Aim

To appreciate that dental erosion may be prevented from occurring or progressing further and, as a result, does not always require restorative operative intervention.

Outcome

After reading this chapter the practitioner should have an understanding of:

-

a range of preventive advice to counter the development/progression of dental erosion

-

the level of the public’s knowledge and understanding concerning dental erosion

-

the importance of the early recognition of dental erosion from both a dental and holistic health care perspective

-

the implications of different forms of restorative treatment for dental erosion and the need to keep avenues open for future treatment needs

-

how to create space for dental restorations

-

the importance of long term follow-up.

Prevention and Treatment

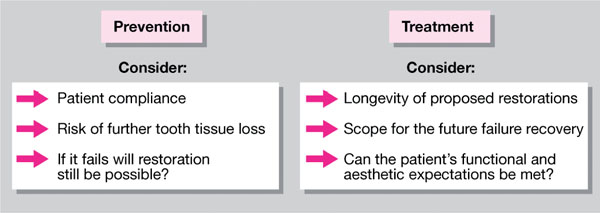

The management of dental erosion in the young adult presents a number of dilemmas to the dentist. The institution of preventive measures has to be weighed against the risk of further loss of tooth substance, complicating or precluding restoration. Any operative intervention needs to be carefully considered for it will have to survive many years. Future options for treatment should be kept as open as possible. Any treatment carried out needs to be recoverable when it fails. Furthermore, the potential for meeting the patients’ often high aesthetic expectations needs to be carefully explored (Fig 4-1). Such decisions are further complicated by the inevitable changes that may occur in both the habits and psychological status of the patient as they progress through adulthood.

Fig 4-1 Prevention versus treatment.

Prevention

The corner stones of this are:

-

education

-

early recognition

-

risk assessment

-

control of further tooth surface loss.

Education

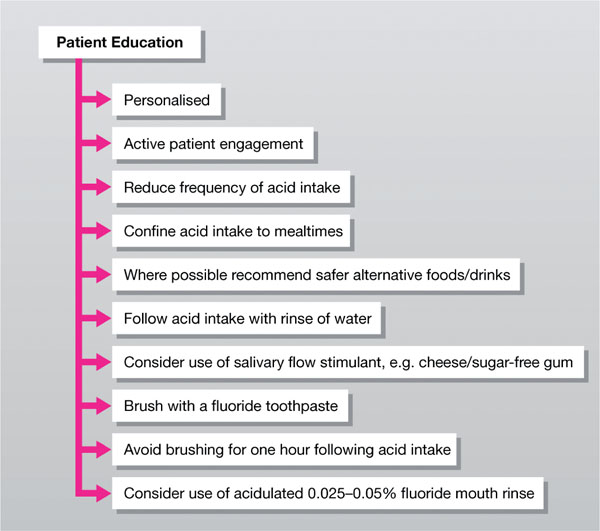

It is essential to actively engage the patient in this process. The success of preventive measures depends greatly upon the active participation of the individual. An early measure of the level of cooperation of the patient is the completion of a dietary diary. Any acidic foods and drinks identified in this by the dental team can serve as a valuable means of initiating a discussion with the patient on the causes and prevention of erosion. This personalises the information given to the patient and promotes a two-way dialogue than the more abstract but true message that acid foods and beverages promote dental erosion. Having caught the imagination of the patient in this way, the opportunity to impart further information should not be lost. This should include advice, where appropriate, to reduce the frequency of acidic intake and to follow such intakes with a rinse of water to aid clearance. Some would also advocate the stimulation of salivary flow following exposure to acid by either chewing sugar-free gum or consuming a neutral food such as cheese. Potential for such action to bring about the remineralisaton of the softened tooth substance should be stressed. It should also be indicated that regular tooth brushing with a fluoride toothpaste both promotes remineralisation and renders the enamel less susceptible to acid attack. Brushing should, however, be delayed until approximately one hour after dietary intake. This is because brushing softened tooth substance may accelerate the erosive process by simply removing mineralised tissue by the mechanical action of the brushing process. Use of a 0.025 – 0.05% non-acidulated fluoride mouth rinse may also be helpful. These points are summarised in Fig 4-2.

Fig 4-2 Patient education.

Wherever possible, acid intake should be confined to meal times, and ‘safer’ alternatives should be indicated to gradually wean a patient of a preferred, but damaging, food or drink. Knowledge of the titratable acidity of various products (see Tables 2-2 and 3-3) or even its determination in the surgery by the dentist (see under Chapter 3 – Special Investigations) in the patients’ presence can be helpful in the educative process. Of course, the ideal would be for all patients to discontinue acidic intake, but this is not always considered realistic.

Recent research on public knowledge of erosion indicates confusion. This spans both those who attend a dentist regularly and those who do not. Although being aware of the term dental erosion, those surveyed tend to be under the impression that such damage is due to sugar consumption and not related to acid. A considerable number, however, implicate the consumption of fizzy drinks in the aetiology of erosion. Faced with such confusion, the educative phase of the consultation is of great importance to maximise the chances of success of any preventive measures.

Early recognition

To minimise the impact of the erosive process upon the dentition, members of the dental team should be vigilant to the signs and symptoms of erosion. These are covered in the section on diagnosis. Any early sign should trigger investigation, with both appropriate advice to the patient and the institution of preventive measures.

Risk assessment

The development of dental erosion is more likely when an individual:

-

has good oral hygiene – the thinner pellicle confers less protection to the tooth surface upon exposure to acid

-

consumes excessive quantities of acidic beverages

-

has an eating disorder that results in vomiting

-

has a medical disorder that is associated either with gastric reflux or vomiting

-

displayed dental erosion as a child.

It is also important to realise that erosion may also be a manifestation of the combined effects of acid intake, softening of the mineralised tooth tissue, compounded further by parafunctional activity such as nocturnal bruxism. This rapidly removes tooth substance, as a result of both mechanical and chemical actions.

Control of further tooth substance loss

This may be achieved by a variety of means either singularly or in combination:-

-

Dietary modification

-

Behaviour modification

-

Dental intervention

-

Medical intervention.

It is essential that the impact upon the loss of tooth substance of these regimes is monitored. At present only sequential study models have found widespread acceptance for this purpose.

Dietary modification – involves the identification of acidic foods and beverages that are consumed by the patient, followed by their elimination or substitution with ‘safer’ alternatives in the diet.

Behaviour modification – the patient should be advised to minimise the frequency of intake of acidic foods and preferably confine these to meal times. Acidic intake should be followed by rinsing with water to aid clearance and chewing sugar-free gum to both promote salivary flow and facilitate remineralisation. Brushing should be delayed for approximately one hour after acidic intake so that the mechanical action does not remove softened tooth substance. The use of a fluoridated toothpaste and rinses with a 0.025–0.05% non-acidulated fluoride mouth rinse should also be encouraged to aid remineralisation and render the enamel less acceptable to acid attack.

For those patients whose erosion is as a consequence of vomiting, it is important that the oral pH is raised to avoid further tooth tissue loss. Chewing sugar-free gum and rinsing the mouth with water or milk as soon as possible thereafter is helpful.

Although recently a commercial product (GC-tooth mousse) (Fig 4-3) based upon the milk protein CPP-ACP (casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate) has become available that both creates a so-called protective and ‘super’ pellicle upon tooth substance and increases the availability of calcium and phosphate for remineralisation (for both professional and instructed patient application), its efficacy in preventing erosion is as yet unclear.

Fig 4-3 GC-tooth mousse – product based upon the milk protein CPP-ACP that is said to both create a protective and ‘super’ pellicle upon tooth substance.

Dental intervention – as well as the professional application of both fluoride and CPP-ACP (see under behaviour modification) the dentist may also consider replacing failed occlusal restorations and carrying out stain removal from the teeth. Failed occlusal restorations should be replaced so as to preserve the original OVD. Staining should be removed professionally in order to limit the potential for further tooth tissue loss by vigorous and injudicious patient tooth cleaning regimes.

Submargination of dental restorations is commonly seen in cases of dental erosion (Fig 4-4). The restorative material is relatively inert to acid attack and unlike the tooth does not undergo a change in morphology. As a result such restorations appear high relative to the affected tooth substance. Although it is tempting to replace the restoration upon failure to conform with the surrounding eroded tooth structure, this should be resisted. Loss of the occlusal height of the restoration will both disrupt the occlusion, by subsequent tooth migration, and over the course of repeated restoration placement and replacement potentially lead to a reduction in the occlusal vertical dimension of the patient, thereby complicating future restorative work. All such restorations should, when failed, be replaced to the original (high) occlusal height. In this regard the use of adhesively bonded onlay restorations will both maintain the occlusal vertical dimension and protect/cover up the eroded occlusal tooth substance.

Fig 4-4 Submargination of occlusal amalgam restoration in the UR4 in a patient with palatal tooth surface loss.

Sometimes patients present with tooth surface loss arising from their attempts to improve upon the appearance of the teeth. This may be as a result of excessive use of whitening kits or because more aggressive means of tooth cleansing, such as cotton buds with lemon juice or brillo pads, have been employed. Where possible, professional stain removal can prevent further uncontrolled tooth surface loss occurring by discouraging inappropriate methods of cleaning.

Medical intervention – when any medication a patient may be receiving is thought to induce vomiting, this should be investigated and the patient referred for a possible change in medication. Those medications whose side-effects include vomiting are listed in Table 3-2. It may also be helpful to refer />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses