chapter 4 Physical and Psychological Evaluation

Before a new patient is treated, it is important that the dentist and staff become acquainted with the patient’s medical history. This is true in all situations, regardless of whether or not the patient is to receive drugs for pain or anxiety control. Because dental care can have a profound effect on both the physical and psychological well-being of the patient, it is extremely important for the person treating the patient to know beforehand the most likely problems to be encountered. It has been stated that “when you prepare for an emergency, the emergency ceases to exist.”1 Prior knowledge of a patient’s physical status enables the dentist to modify the proposed treatment plan to better meet the patient’s limit of tolerance. This is of special importance whenever the administration of a drug for the management of pain (e.g., local anesthetic) or anxiety (e.g., CNS depressant) is planned. The administration of certain drugs used in dentistry is specifically (relatively or absolutely) contraindicated in patients with some disease states. Knowledge of these contraindications is critical if potentially serious complications are to be prevented.

GOALS OF PHYSICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL EVALUATION

In the following discussion, a comprehensive but easy-to-use program of physical evaluation is described.2,3 Used as recommended, it allows the dentist to accurately determine any potential risk presented by the patient before the start of treatment. The following are the goals that are sought in the use of this system:

PHYSICAL EVALUATION

Medical History Questionnaire

In recent years, computer-generated medical history questionnaires have been developed.4,5 These questionnaires permit patients to enter their responses to questions electronically on a computer. Whenever a positive response is given, the computer asks additional questions related to the positive response. In effect the computer asks the questions called for in the dialogue history.

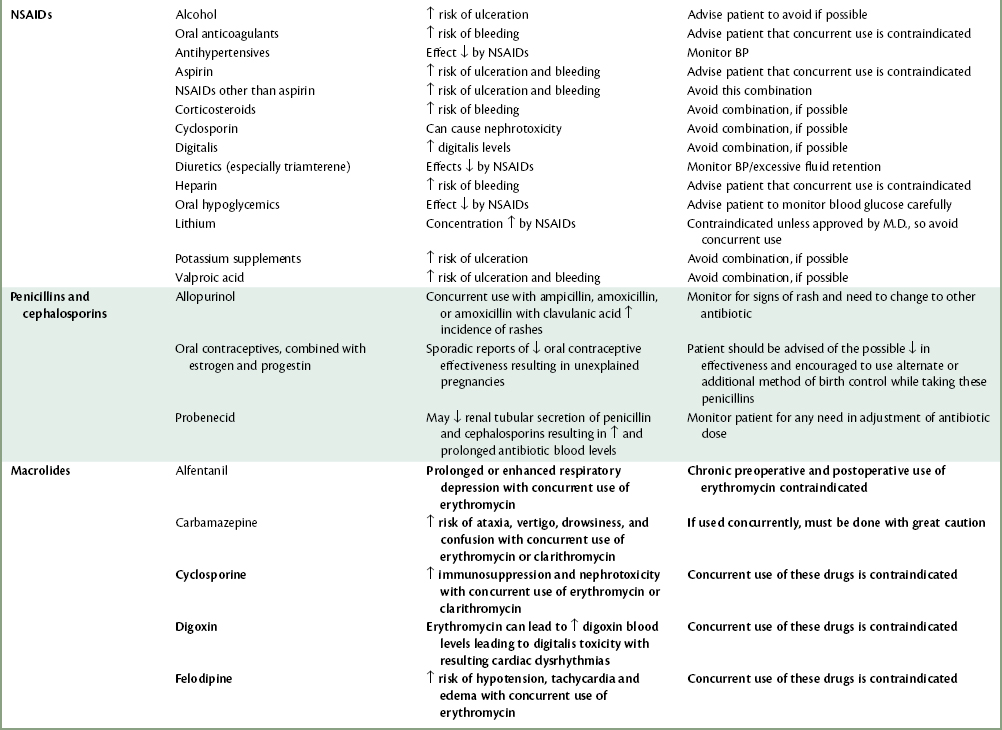

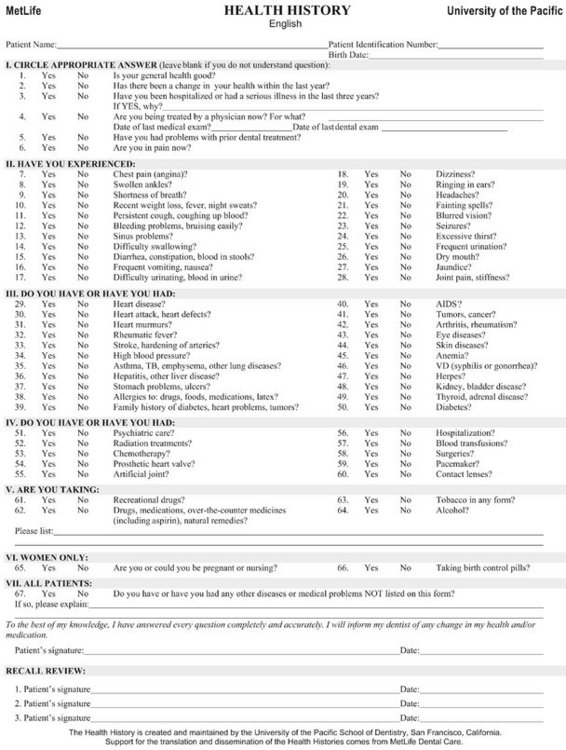

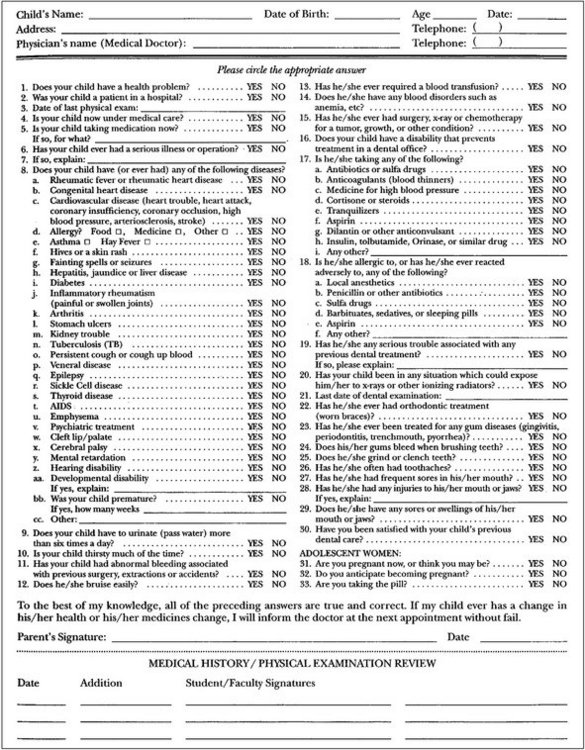

In this fifth edition of Sedation, I have included as the prototypical adult health history questionnaire one that has been developed by the University of the Pacific (UOP) School of Dentistry in conjunction with MetLife (Figure 4-1). Figure 4-2 is an example of a pediatric medical history questionnaire.

Figure 4-1 Adult health history questionnaire.

(Reprinted with permission from University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in San Francisco, CA.)

Figure 4-2 Pediatric medical history questionnaire.

(From Malamed SF: Medical emergencies in the dental office, ed 6, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

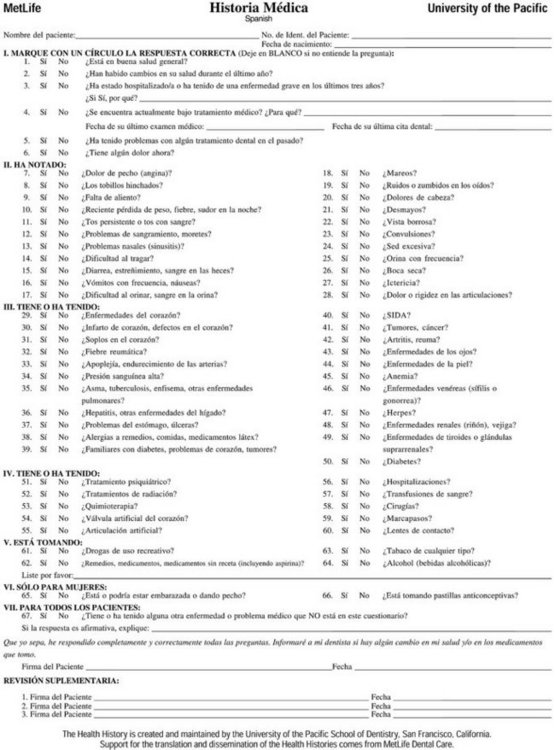

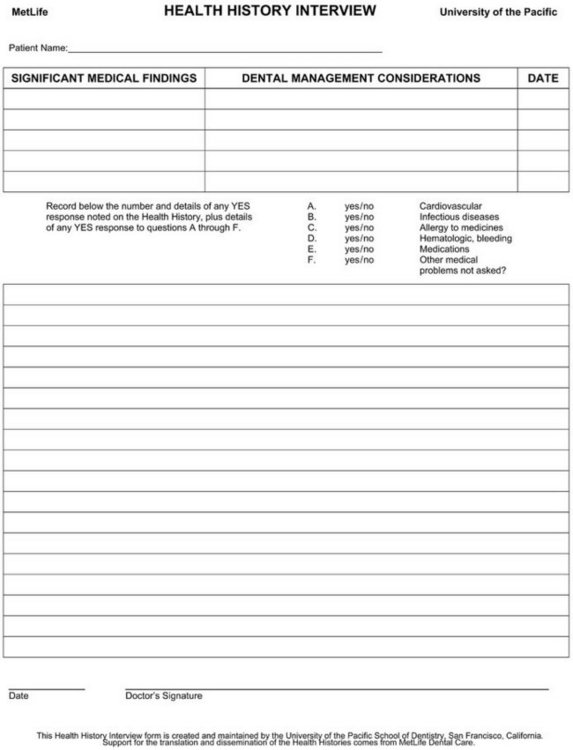

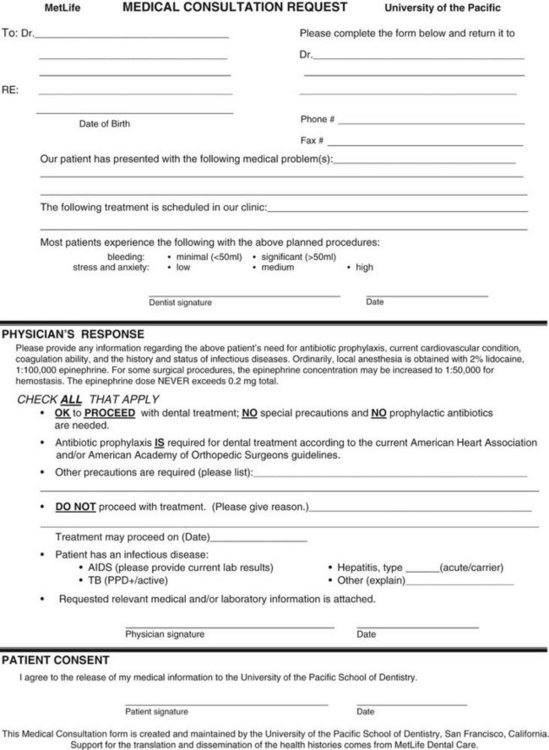

This health history has been translated into 36 different languages, comprising the languages spoken by 95% of the persons on this planet. The cost of the translation was supported by several organizations including the California Dental Association, but most extensively by MetLife Dental. The health history (see Figure 4-1), translations of the health history (Figure 4-3), the interview sheet (Figure 4-4), medical consultation form (Figure 4-5), and protocols for the dental management of medically complex patients may be found on the University of the Pacific’s website at www.dental.pacific.edu under Dental Professionals and then under Health History Forms. Protocols for management of medically complex patients can be found at the same website under Pacific Dental Management Protocols. Translations of the medical history form can also be found at www.metdental.com under Multi-Language Medical Health History Forms Available.

Figure 4-3 Spanish health history questionnaire.

(Reprinted with permission from University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in San Francisco, CA.)

Figure 4-4 Health history interview sheet.

(Reprinted with permission from University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in San Francisco, CA.)

Figure 4-5 Medical consultation form.

(Reprinted with permission from University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in San Francisco, CA.)

Following is the UOP medical history questionnaire with a discussion of the significance of each:

Medical History Questionnaire (see Figure 4-1)

COMMENT: A general survey question seeking the patient’s general impression of their health. Studies have demonstrated that a YES response to this question does not necessarily correlate with the patient’s actual state of health.5

COMMENT: A history of angina (defined, in part, as chest pain brought on by exertion and alleviated by rest) usually indicates the presence of a significant degree of coronary artery disease with attendant ischemia of the myocardium. The risk factor for the typical patient with stable angina is ASA 3.* Stress reduction is strongly recommended in these patients. In the presence of dental fears, sedation is absolutely indicated in the anginal patient. Inhalation sedation with N2O-O2 is preferred. Patients with unstable or recent-onset angina represent ASA 4 risks.

The occurrence of respiratory problems during sedation and general anesthesia is increased in patients who have URIs and within the following 2 weeks.6

COMMENT: A multitude of causes can lead to nausea and vomiting. Medications, however, are among the most common causes of nausea and vomiting.7–9 Opiates, digitalis, levodopa, and many cancer drugs act on the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the area postrema to induce vomiting. Drugs that frequently induce nausea include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), erythromycin, cardiac antidysrhythmics, antihypertensive drugs, diuretics, oral antidiabetic agents, oral contraceptives, and many GI drugs, such as sulfasalazine.7–9

COMMENT: Heart attack is the lay term for myocardial infarction (MI). The dentist must determine the time that has elapsed since the patient suffered the MI, the severity of the MI, and the degree of residual myocardial damage to decide whether or not treatment modifications are indicated. Elective dental care should be postponed 6 months after an MI.10 Most post-MI patients are considered to be ASA 3 risks; however, a patient who has experienced an MI fewer than 6 months before the planned dental treatment should be considered an ASA 4 risk. Where little or no residual damage to the myocardium is present, the patient may be considered an ASA 2 risk after 6 months.

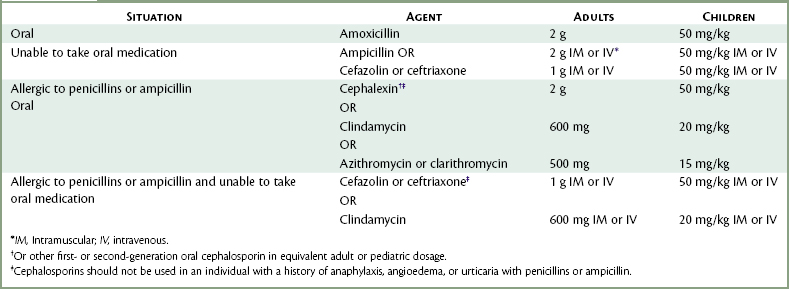

COMMENT: Heart murmurs are common, and not all murmurs are clinically significant. The dentist should determine whether a murmur is functional (nonpathologic, or ASA 2) or whether clinical signs and symptoms of either valvular stenosis or regurgitation are present (ASA 3 or 4) and whether antibiotic prophylaxis is warranted. A major clinical symptom of a significant (organic) murmur is undue fatigue. Table 4-1 provides guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis. These were most recently revised in 2007.11 Box 4-1 categorizes cardiac problems as to their requirements for antibiotic prophylaxis, and Box 4-2 addresses prophylaxis and dental procedures specifically. Guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in orthopedic patients with joint replacements were last published in 1997.12

Box 4-1

Cardiac Conditions Associated With the Highest Risk of Adverse Outcome from Endocarditis for Which Prophylaxis With Dental Procedures Is Recommended

Box 4-2

Dental Procedures for Which Endocarditis Prophylaxis Is Recommended for Patients

All dental procedures that involve manipulation of gingival tissue or the periapical region of teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa*

* The following procedures and events do not need prophylaxis: routine anesthetic injections through noninfected tissue, taking dental radiographs, placement of removable prosthodontic or orthodontic appliances, adjustment of orthodontic appliances, placement of orthodontic brackets, shedding of deciduous teeth, and bleeding from trauma to the lips or oral mucosa.

Emphysema is a form of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), also called chronic obstructive lung disease (COLD). The emphysematous patient has a decreased respiratory reserve from which to draw if the body’s cells require additional O2, which they do during stress. Supplemental O2 therapy during dental treatment is recommended in severe cases of emphysema; however, the severely emphysematous (ASA 3, 4) patient should not receive more than 3 L of O2 per minute.13 This flow restriction helps to ensure that the dentist does not eliminate the patient’s hypoxic drive, which is the emphysematous patient’s primary stimulus for breathing. The emphysematous patient is an ASA 2, 3, or 4 risk depending on the degree of disability.

COMMENT: These diseases or problems either are transmissible (hepatitis A and B) or indicate the presence of hepatic dysfunction. A history of blood transfusion or of past or present drug addiction should alert the dentist to a probable increase in the risk of hepatic dysfunction. (Hepatic dysfunction is a common finding in the parenteral drug abuse patient.) Hepatitis C is responsible for more than 90% of cases of posttransfusion hepatitis, but only 4% of cases are attributable to blood transfusions; up to 50% of cases are related to IV drug use. Incubation of hepatitis C averages 6 to 7 weeks. The clinical illness is mild, usually asymptomatic, and characterized by a high rate (>50%) of chronic hepatitis.14 Because most drugs are biotransformed in the liver, care must be taken when selecting specific drugs and techniques of administration in the patient with significant hepatic dysfunction. Inhalation sedation with N2O-O2 is not contraindicated in these patients.

COMMENT: Skin represents an elastic, rugged, self-regenerating, protective covering for the body. The skin also represents our primary physical presentation to the world and as such displays a myriad of clinical signs of disease processes including allergy, cardiac, respiratory, hepatic, and endocrine disorders.15

In addition, congenital or idiopathic methemoglobinemia, though rare, is a relative contraindication to the administration of the amide local anesthetic prilocaine.16

COMMENT: The dentist should evaluate the nature of the renal disorder. Treatment modifications including antibiotic prophylaxis may be appropriate for several chronic forms of renal disease. Functionally anephric patients are ASA 4 risks, whereas patients with most other forms of renal dysfunction are either ASA 2 or 3 risks. Box 4-3 shows a sample dental referral letter for a patient on long-term hemodialysis treatment because of chronic kidney disease.

Box 4-3

Hemodialysis Letter

The greatest concerns during dental treatment relate to the possible effects of the dental care on subsequent eating and development of hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). Patients leaving a dental office with residual soft tissue anesthesia, especially in the mandible, usually defer eating until sensation returns, a period potentially of 3 to 5 (lidocaine, mepivacaine, articaine, prilocaine with vasoconstrictor) or more (up to 12 hours) hours (bupivacaine with vasoconstrictor). Diabetic patients have to modify their insulin doses if they do not maintain normal eating habits. Administration of the recently released local anesthetic reversal agent, phentolamine mesylate, at the conclusion of dental treatment can minimize residual soft tissue anesthesia by up to 50%.17

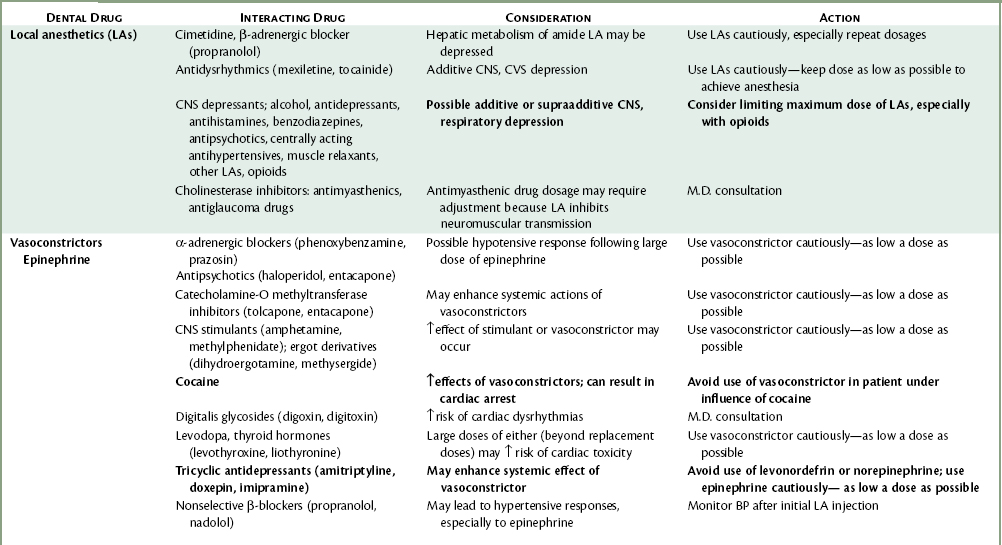

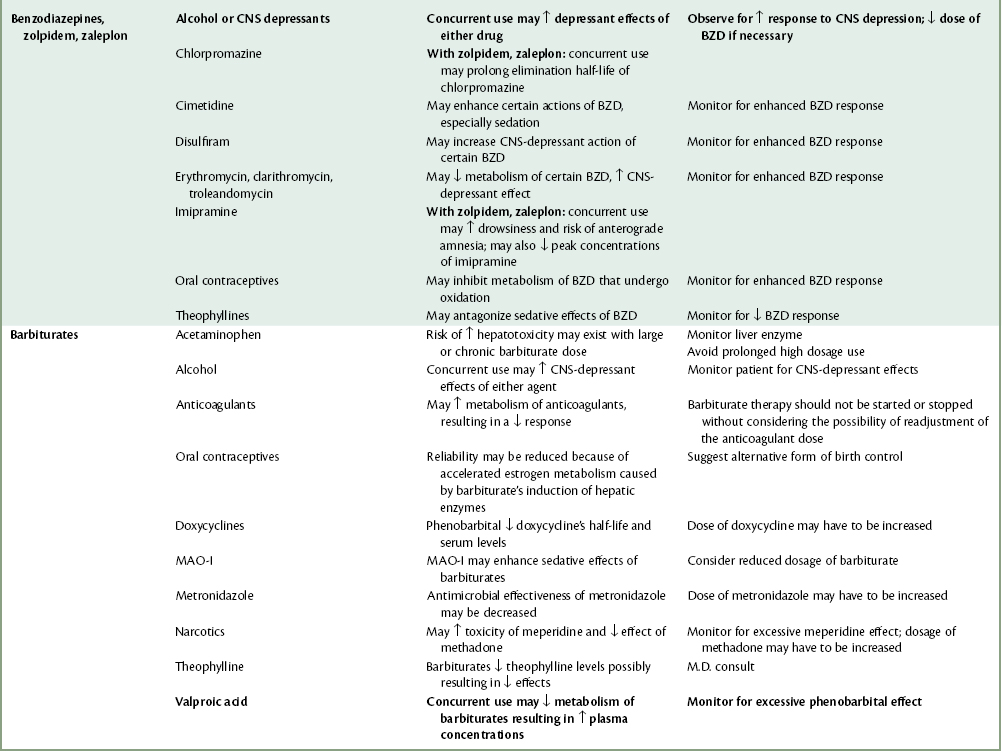

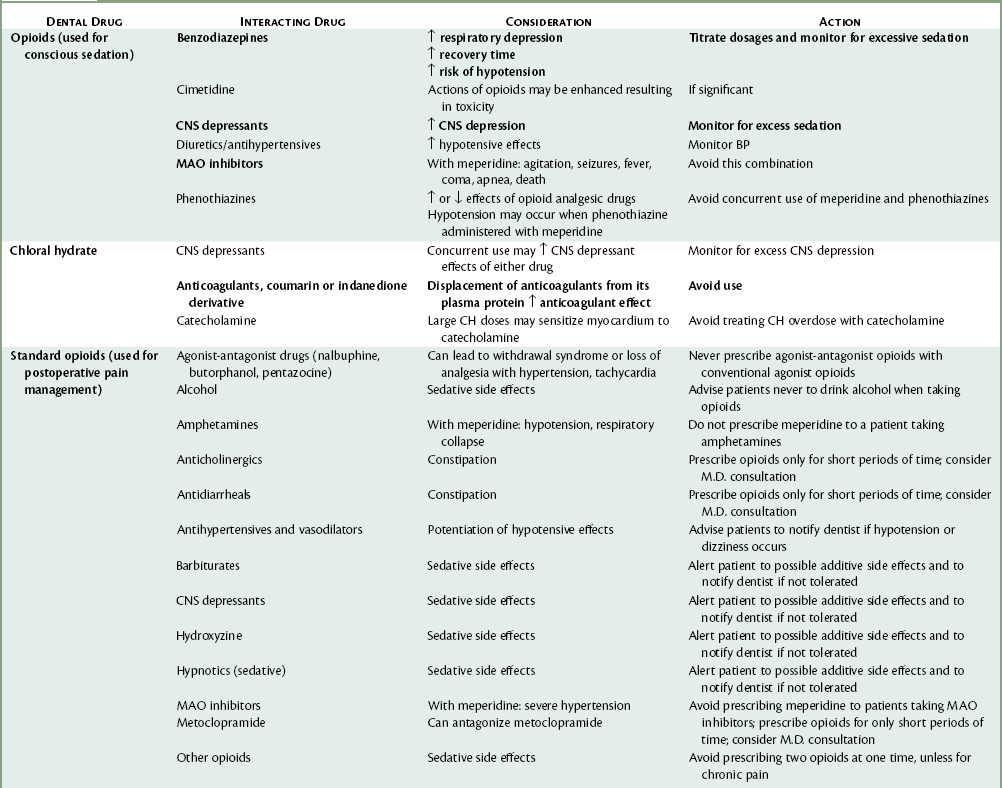

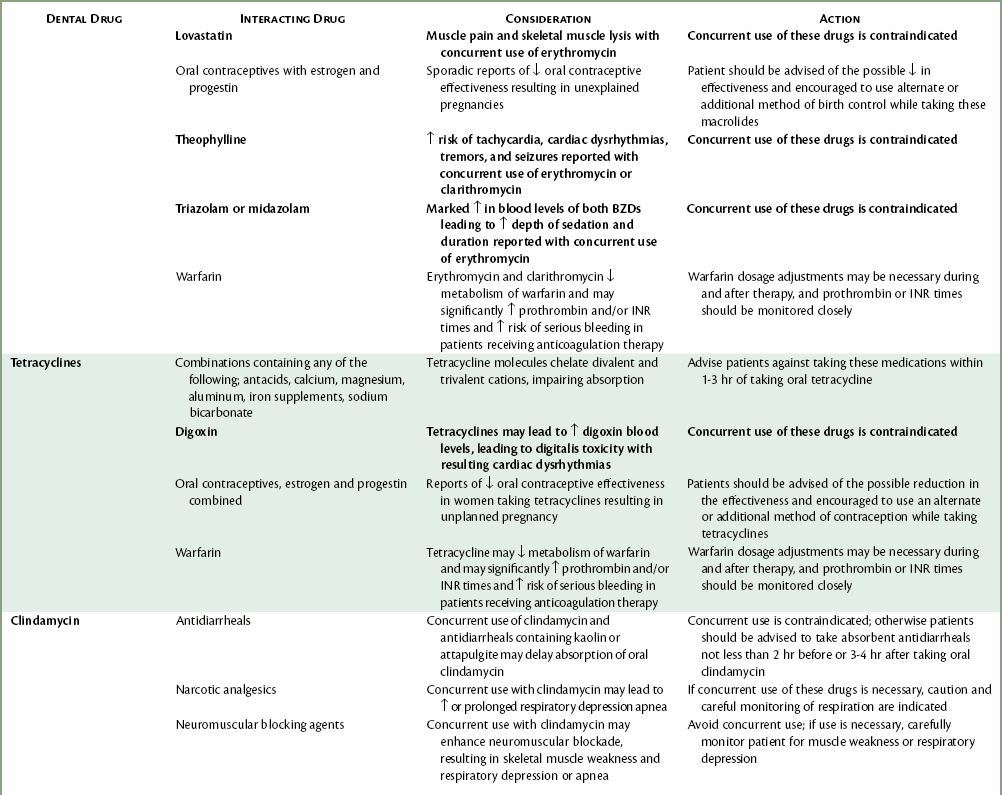

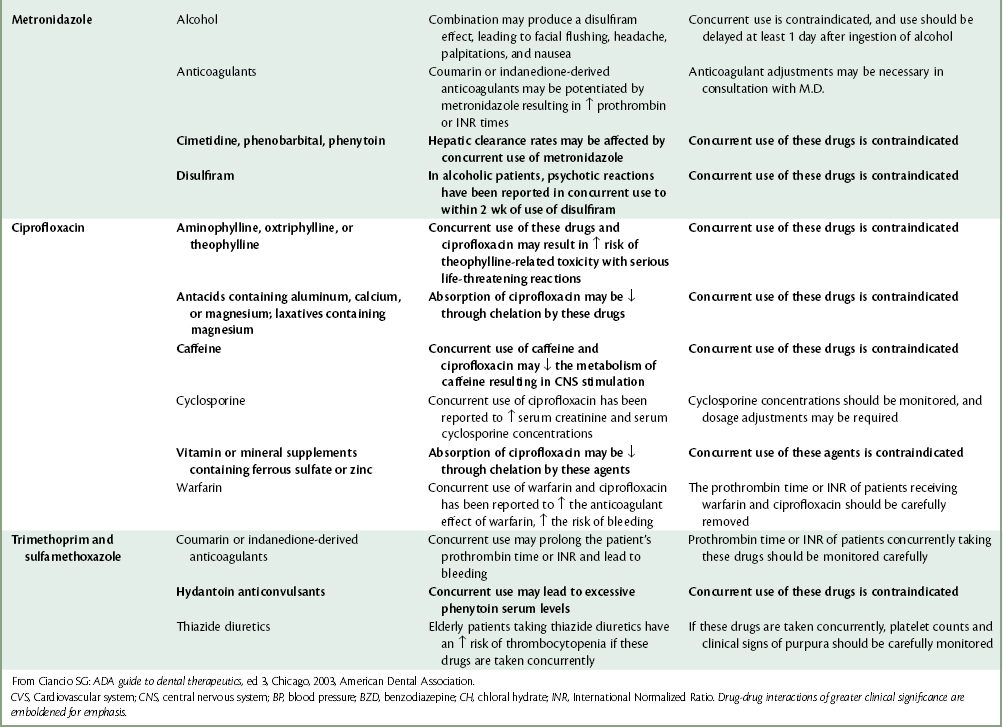

COMMENT: The dentist should be aware of any nervousness (in general or specifically related to dentistry) or history of psychiatric care before treating the patient. Such patients may be receiving a number of drugs to manage their disorders that might interact with drugs the dentist uses to control pain and anxiety (Table 4-2). Medical consultation should be considered in such cases. Extremely fearful patients are ASA 2 risks, whereas patients receiving psychiatric care and drugs represent 2 or 3 risks.

COMMENT: Patients with prosthetic (artificial) heart valves are no longer uncommon. The dentist’s primary concern is to determine if antibiotic prophylaxis is required. Antibiotic prophylactic protocols were presented earlier in this chapter.11,12 The dentist should be advised to consult with the patient’s physician (e.g., the cardiologist or cardiothoracic surgeon) bef/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses