Infectious Diseases

After studying this chapter, the student will be able to:

1. State the difference between an inflammatory and an immune response to infection.

2. Describe the factors that allow opportunistic infection to develop.

3. List two examples of opportunistic infections that can occur in the oral cavity.

4. For each of the following infectious diseases, name the organism causing it, list the route or routes of transmission of the organism and the oral manifestations of the disease, and describe how the diagnosis is made: impetigo, tuberculosis, actinomycosis, syphilis (primary, secondary, tertiary), verruca vulgaris, condyloma acuminatum, and primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.

5. Describe the relationship between streptococcal tonsillitis, pharyngitis, scarlet fever, and rheumatic fever.

6. List and describe four forms of oral candidiasis.

7. Describe the clinical features of herpes labialis.

8. Describe the clinical features of recurrent intraoral herpes simplex infection and compare them with the clinical features of minor aphthous ulcers.

9. Describe the clinical characteristics of herpes zoster when it affects the skin of the face and oral mucosa.

10. List two oral infectious diseases for which a cytologic smear may assist in confirming the diagnosis.

11. List four diseases associated with the Epstein-Barr virus.

12. List two diseases caused by coxsackieviruses that have oral manifestations.

13. Describe the spectrum of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, including initial infection and the development of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

14. List and describe the clinical appearance of five oral manifestations of HIV infection.

Bacterial Infections

Impetigo

Tuberculosis

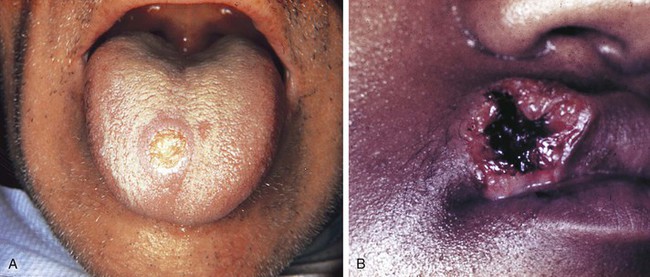

Oral lesions associated with tuberculosis occur but are rare. They most likely appear when organisms are carried from the lungs in sputum and transmitted to the oral mucosa (Figure 4-1). The tongue and palate are the most common sites for oral lesions of tuberculosis, but they may occur anywhere in the oral cavity, even in bone as in osteomyelitis. Oral lesions appear as painful, nonhealing, slowly enlarging ulcers that can be either superficial or deep.

Actinomycosis

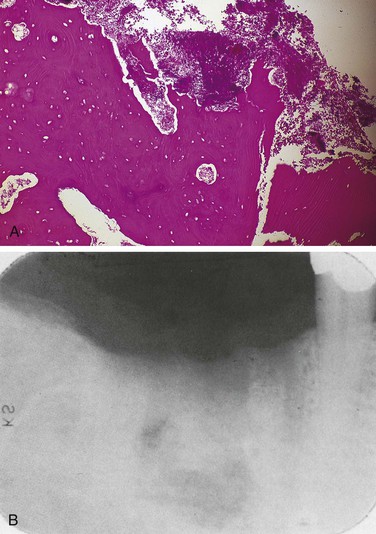

The most characteristic form of the disease is the formation of abscesses that tend to drain by the formation of sinus tracts (Figure 4-2). The colonies or organisms appear in the pus as tiny, bright yellow grains and are called sulfur granules because of their yellow color. The organisms can also be identified by microscopic examination. These organisms are common inhabitants of the oral cavity. It is not clear why they only occasionally cause disease. Predisposing factors have not been identified. The infection is often preceded by tooth extraction or an abrasion of the mucosa.

Syphilis

The disease occurs in three stages: (1) primary, (2) secondary, and (3) tertiary (Table 4-1). The lesion of the primary stage, called the chancre, is highly infectious and forms at the site at which the spirochete enters the body (Figure 4-3). Regional lymphadenopathy accompanies the chancre. The lesion heals spontaneously after several weeks without treatment, and the disease enters a latent period.

TABLE 4-1

| STAGE | ORAL LESION |

| Primary | Chancre |

| Secondary | Mucous patch |

| Latent | None |

| Tertiary | Gumma |

Congenital Syphilis

Syphilis can be transmitted from an infected mother to the fetus because the organism can cross the placenta and enter the fetal circulation. Congenital syphilis often causes serious and irreversible damage to the child, including facial and dental abnormalities. The developmental disorders that result from fetal and neonatal syphilis are described in Chapter 5.

Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) was formerly called acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG). This condition is more chronic than acute and therefore, is most appropriately called NUG. It is a painful erythematous gingivitis with necrosis of the interdental papillae (Figure 4-4). NUG is usually caused by a combination of a fusiform bacillus and a spirochete (Borrelia vincentii) and is associated with decreased resistance to infection.

The gingiva is painful and erythematous, with necrosis of the interdental papillae generally accompanied by a foul odor and metallic taste. The necrosis results in cratering of the interdental papillae area. Sloughing of the necrotic tissue presents as a pseudomembrane over the tissues. Systemic manifestations of infection such as fever and cervical lymphadenopathy may be present. Clinical features distinguish NUG from acute marginal gingivitis and the gingival component of acute primary herpes simplex infection (see Figure 4-20, B).

Pericoronitis

Pericoronitis is an inflammation of the mucosa around the crown of a partially erupted, impacted tooth (Figure 4-5). The soft tissue around the mandibular third molar is the most common location for pericoronitis. The inflammation is usually the result of infection by bacteria that are part of the normal oral microflora, which proliferate in the pocket between the soft tissue and the crown of the tooth. Compromised host defenses, ranging from minor illnesses to immunodeficiency, are associated with an increased risk of pericoronitis. Trauma from an opposing molar and impaction of food under the soft tissue flap (operculum) covering the distal portion of the third molar may also precipitate pericoronitis.

Acute Osteomyelitis

Acute osteomyelitis involves acute inflammation of the bone and bone marrow (Figure 4-6, A). Acute osteomyelitis of the jaws is most commonly a result of the extension of a periapical abscess. It may follow fracture of the bone or surgery, and may also result from bacteremia.

Chronic Osteomyelitis

Chronic osteomyelitis is a long-standing inflammation of bone. It may occur in inadequately treated acute osteomyelitis, long-term inflammation of bone with no recognized acute phase, Paget disease, sickle cell disease, or bone irradiation that results in decreased vascularity. The involved bone is painful and swollen, and radiographic examination reveals a diffuse and irregular radiolucency that can eventually become radiopaque as bone forms within the chronically inflamed tissue (Figure 4-6 B). When radiopacity develops, the condition is called chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis. Recently, cases of osteonecrosis of the mandible and maxilla have been reported in patients taking bisphosphonate medication. This may appear clinically similar to chronic osteomyelitis. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis is described in Chapter 9.

Fungal Infections

Candidiasis

Candidiasis, also called candidosis, moniliasis, and thrush, occurs as a result of an overgrowth of the yeastlike fungus Candida albicans. It is the most common oral fungal infection. This fungus is part of the normal oral microflora in many individuals, particularly those individuals with diabetes mellitus and those who wear dentures. Overgrowth of Candida albicans is associated with many different conditions (Box 4-1).

Types of Oral Candidiasis

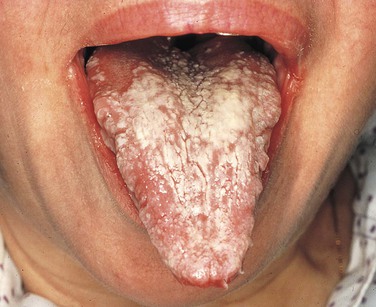

Pseudomembranous Candidiasis

A white curdlike material is present on the mucosal surface in pseudomembranous candidiasis (Figure 4-7). The underlying mucosa is erythematous. On occasion, a burning sensation is felt, and the patient may complain of a metallic taste.

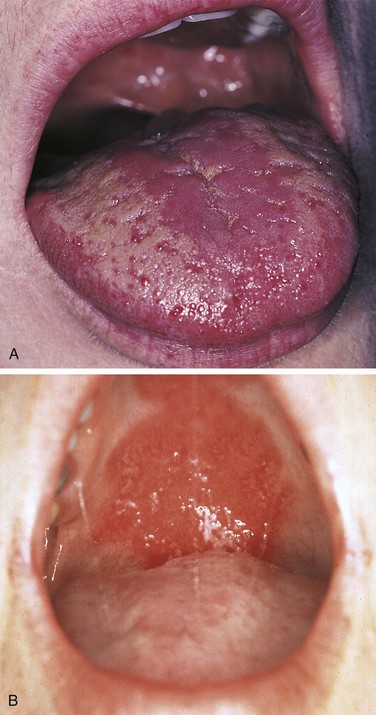

Erythematous Candidiasis

An erythematous, often painful, mucosa is the presenting complaint in erythematous candidiasis (Figure 4-8). This type of candidiasis may be localized to one area of the oral mucosa or be more generalized. Irregular, patchy depapillation of the tongue is often seen in this type of candidiasis.

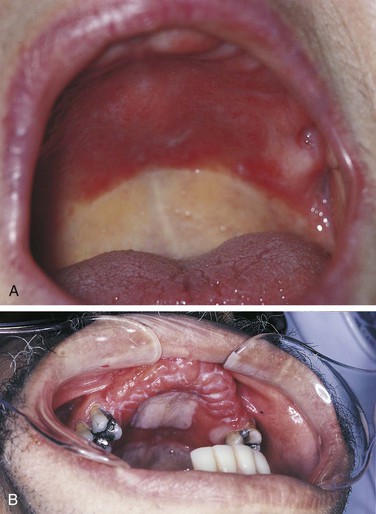

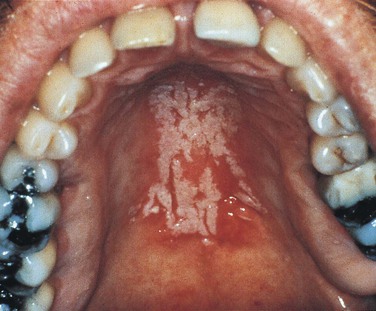

Denture Stomatitis

Denture stomatitis is the most common type of candidiasis affecting the oral mucosa. It is also called chronic atrophic candidiasis (Figure 4-9). This type of candidiasis also presents as erythematous mucosa, but the erythematous change is limited to the mucosa covered by a full or partial denture. The lesions may vary from petechiae-like to more generalized and granular. It is most common on the palate and maxillary alveolar ridge. Denture stomatitis is asymptomatic and is usually discovered by the dentist or dental hygienist during a routine oral examination.

Chronic Hyperplastic Candidiasis

Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis (Figure 4-10) appears as a white lesion that does not wipe off the mucosa. Candidal leukoplakia and hypertrophic candidiasis are other names for this type of oral candidiasis. An important diagnostic feature of this type of candidiasis is its response to antifungal medication: when leukoplakia is caused by candidiasis, it disappears when treated with antifungal medication (therapeutic diagnosis). If the lesion does not respond to antifungal therapy, biopsy should be considered to establish the diagnosis of the lesion.

Angular Cheilitis

Candida organisms are often the cause of angular cheilitis (Figure 4-11), especially if saliva collects at the corners of the mouth. It appears as erythema or fissuring at the labial commissures. Angular cheilitis may be caused by other factors such as nutritional deficiency or a combination of candidiasis and bacterial infection; however, it most commonly results from Candida infection. Angular cheilitis frequently accompanies intraoral candidiasis.

Median Rhomboid Glossitis (Central Papillary Atrophy)

Several studies have reported an association between median rhomboid glossitis (Figure 4-12) also called central papillary atrophy and candidiasis. It appears as an erythematous, often rhombus-shaped, flat-to-raised area on the midline of the posterior dorsal tongue. Candida organisms have been identified in some lesions, and some lesions disappear with antifungal treatment. However, the response to antifungal treatment is not consistent; therefore, although this lesion has been associated with candidiasis, the cause is not yet clear.

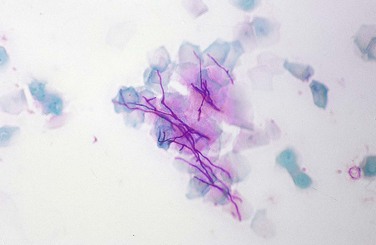

Diagnosis and Treatment

Because Candida is part of the oral microflora in many individuals, a culture is not useful for diagnosis. A positive culture result indicates that the organisms are present but not that they are causing infection. Clinical features and the use of the mucosal smear/cytologic preparation (Figure 4-13) are usually more helpful. The surface of the lesion is scraped vigorously with a tongue blade, wooden spatula, or specially designed brush; and the scrapings are spread on a glass slide and fixed with alcohol. The slide is then sent to an oral pathology laboratory for staining and examination. In addition to the smear, the response of the lesion to antifungal treatment is important in confirming the diagnosis of candidiasis. Lesions caused by Candida should resolve with antifungal treatment. Both topical and systemic medications are used for candidiasis. However, in some patients, particularly those who are immunocompromised, candidiasis is persistent and recurrent.

Deep Fungal Infections

Diagnosis

The initial signs and symptoms of these deep fungal infections are usually related to the primary lung infection. Oral lesions are preceded by pulmonary involvement. These oral lesions are chronic, nonhealing ulcers that can resemble squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 4-14). Diagnosis is made by biopsy and microscopic examination. Special staining of the tissue reveals the organisms, which can be identified by their microscopic appearance. The tissue can also be cultured; this is useful in establishing the diagnosis.

Viral Infections

Human Papillomavirus Infection

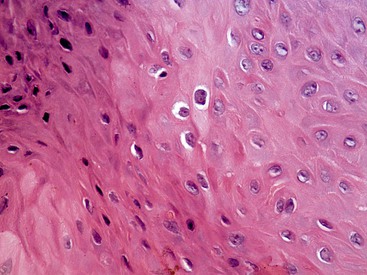

Human papillomavirus (HPV) selectively infects skin and oral mucosa. Infection occurs by direct contact. More than 150 different types of HPV have been identified; some of these types have been found to cause neoplasia and therefore are called high-risk types. Others that cause benign lesions or are not associated with lesions are called low-risk types. At least 40 different types of HPV have been identified in oral mucosa. A recent study that examined both high-risk and low-risk types of HPV in the oral cavity found the overall prevalence of HPV in the oral cavity to be 6.9%. This included both high-risk and low-risk types. HPV has been clearly associated with carcinoma of the vaginal cervix (cervical cancer). High-risk types have been identified and associated with squamous cell carcinomas that form in the oropharyngeal region (see Chapter 7). Evidence of their role in the pathogenesis of these cancers is emerging, but is not yet completely clear.

Like other viruses, HPV incorporates itself into the nuclear material of infected cells. HPV-infected cells, called koilocytes, are characterized microscopically by an irregular nucleus surrounded by clear cytoplasm (Figure 4-15).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)