Chapter 4

Ethical Considerations

Ethics is a branch of philosophy and theology and can be described as the “study of what is right and good with respect to conduct and character”. Others define it as “a framework for human conduct that relates to moral principles and attempts to distinguish right from wrong” (Miesing and Preble 1985) or “a system of moral principles, by which human actions and proposals may be judged good or bad or right or wrong” (Macquarie Dictionary of Australian English).

It is a body of principles or standards of human conduct that govern the behaviour of individuals and groups. In clinical practice, ethical principles should shape our attitude and approach to patient care.

Given the business aspects of general dental practice, dentists may find themselves in situations where the decision-making process is challenged by the conflicting ethical demands of healthcare and business. Writing in the Journal of the Canadian Dental Association, Ronald Wiebe (2000) expressed the view: “The private practitioner surviving on elective services is torn between the patient-first ethos of the healer and the survival-of-the-fittest demands of private enterprise.” Thus, the challenge is to try and close the ethical gap (real or perceived) that may exist between the health-led objective of delivering quality dental care and the business objective of producing a profit.

But this viewpoint is not restricted to healthcare professionals. Lord Nolan, writing in Perspectives, a financial business publication, stated: “The ability to identify and manage business risks is as important to an organisation’s ethical framework as its ethical framework is to its risk management programme.”

Ethics is integral to risk management because:

-

The conduct of dentists is measured against ethical guidance issued by professional regulatory bodies.

-

A significant proportion of complaints are instigated as a result of what patients perceive as unethical behaviour.

-

The risk of breaching the ethical code damages reputation, causes stress and in extreme cases may result in dentists being removed from professional registers.

-

When legal and risk management issues arise in the delivery of healthcare, they are often compounded by ethical issues.

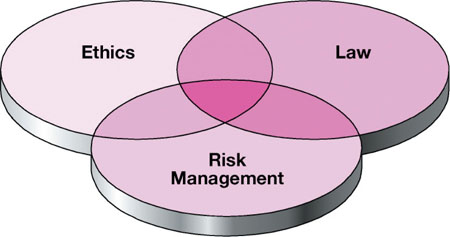

We must also be aware that what may originally have come to light as an ethical dilemma may also raise legal and risk management concerns (see Fig 4-1). The fundamental difference amongst these three areas is that the ethical view reflects the “ought to” perspective, the legal view is the “have to” viewpoint and the risk management view is the “choose to” approach.

Fig 4-1 The relationship between law, ethics and risk management.

It is interesting to observe attitudes amongst professionals. There is a variation that is related to age – studies have shown that older healthcare professionals have an increased interest in ethics and attach greater importance to ethical behaviour in practice. One reason offered for this is that older practitioners are more financially secure and under less pressure to compromise their principles. They also have more to lose – reputation risk – if caught in an unethical situation and therefore are unwilling to place themselves at risk. The older generation tends to be naturally geared to risk management whereas the younger generation may not be.

Ethical Relationship

In recent years, media coverage of dentistry on both sides of the Atlantic has highlighted issues which give rise to reputation risk. Chief amongst these has been the variations in prescribing and treatment planning amongst dentists.

Amongst a variety of reports to highlight the concerns, a reporter in the US visited 50 different practices and received quotes for treatment. These varied from nothing to more than $9,000. The report appeared on the Marketplace website and stated: “Improvements in dental care have meant less work for dentists to do, even as the number of dentists is increasing. This has lead to growing concern about dental fraud, in which dentists might bill for work they did not perform, or perform work which is not necessary.” It concluded by advising patients that they had the right “to file a complaint with the dental licensing body” if they had concerns about these issues. Similar reports have appeared in the British media.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the variance in prescribing patterns and treatment planning amongst dentists and concluded that there are often perfectly legitimate reasons for the variations. But hype and hyperbole often displace science and logic when it comes to shaping consumer opinion.

What can be done about this? The answer lies in one of the many mantras of successful business: “We do business with those we trust; we get business from those who trust us.” We should remember that ethical conduct is the key to long-term success in all businesses.

This view is reflected by Bob Dunn, President and CEO of San Francisco-based Business for Social Responsibility, who states: “Ethical values, consistently applied, are the cornerstones in building a commercially successful and socially responsible business.”

Ethics and Complaints

Situations that pose the greatest risk to practitioners are those in which legal and ethical standards define what is considered appropriate professional behaviour. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of complaints relating to professional conduct. Investigations into professional conduct can damage reputations and ruin professional careers.

It is often the “ought to” element that can trigger complaints from patients who experience what they believe to be unacceptable ethical standards. Given the potential seriousness of such complaints – even if they have no substance, their investigation by the professional regulatory body is stressful enough – we should be aiming to promote the ethical aspects of our practising philosophy. Few mission statements include this important reference.

Ethics and Philosophy

The principles of ethical reasoning are useful tools for sorting out the good and bad components within complex human interactions. For this reason the study of ethics has been at the heart of intellectual thought since the early Greek philosophers.

Socrates argued that the determination of good or bad behaviour depended entirely on the integrity of the rational process. Plato, whose dialogues with Socrates have presented historians with some challenging questions regarding whose ideas they were in the first place, believed that to know good was to do good, that doing good was more useful and rational than doing bad, and that immoral behaviour was largely the result of ignorance.

Aristotle (a student at Plato’s academy) contributed to ethics through expressing views based on deduction and logic. Aristotle’s name for logic was “analytics” – he argued that ethics was a purely logical outcome of human nature and that it was useful because it was logical.

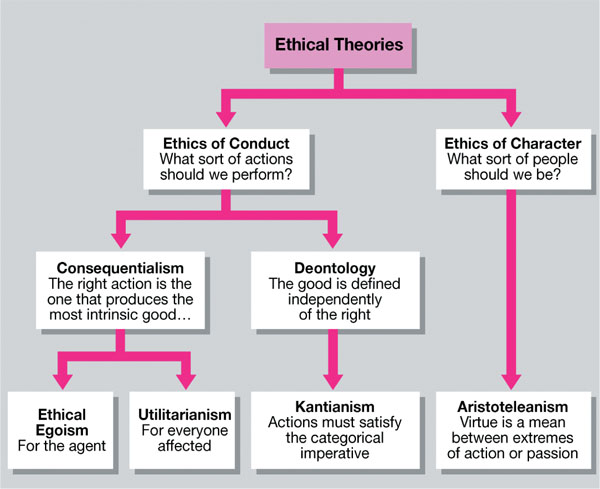

The contribution of the Greek philosophers has helped to develop ethical principles. In practice, we adjust our values, thinking, and behaviour to reflect ethical principles. The two principal ethical theories are the utilitarian and the deontological theories (Fig 4-2).

Fig 4-2 Ethical theories.

Consequentialism

This is also called utilitarian or tele/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses