Dental Anatomy

Learning Objectives

1 Pronounce, define, and spell the Key Terms.

2 Explain the composition of each of the tissues of a tooth.

3 Use the correct terminology when describing the teeth.

4 Describe the locations of all surfaces of the teeth.

5 Identify the number of teeth in the primary dentition.

6 Identify the correct location of each permanent tooth.

Key Terms

Anatomic Crown

Apex

Apical

Bifurcation

Cementoenamel Junction

Cementum

Clinical Crown

Contact Point

Cusp

Dentin

Dentinal Fiber

Dentinal Tubules

Embrasure

Enamel

Enamel Prisms

Exfoliation

Federation Dentaire Internationale (FDI)

Fossae

International Standards Organization System (ISO)

Mixed Dentition

Numbering Systems

Palmer Notation System

Periapical

Periodontal Ligament

Periodontium

Permanent Dentition

Primary Dentition

Pulp

Trifurcation

Universal/National System

In this chapter you will learn the anatomic parts of the tooth and the names and locations of the various types of teeth in the human dentition. You will also learn their functions and features. In preparation for learning dental charting, you will learn the common systems of tooth numbering.

Anatomic Parts of the Tooth

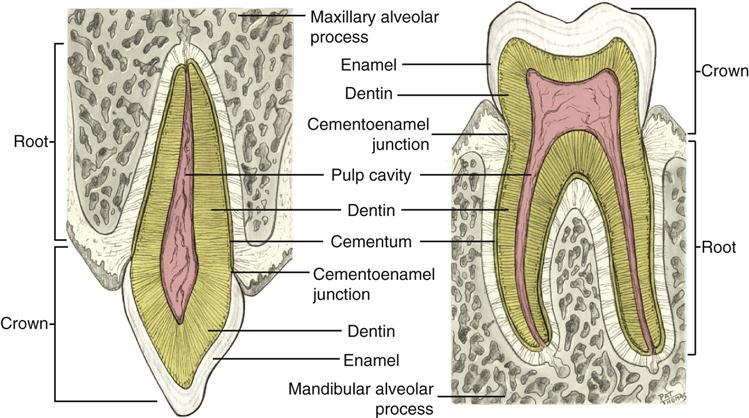

Each tooth consists of a crown and one or more roots. The size and shape of the crown and the size and number of roots vary according to the type of the tooth (Figure 4-1).

Crown

Anatomic Crown

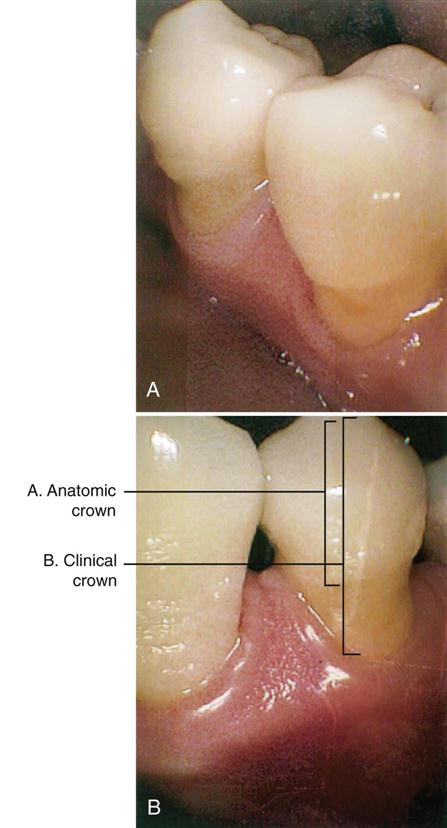

The anatomic crown is the portion of the tooth covered with enamel (Figure 4-2). The size of the anatomic crown remains the same throughout the life of the tooth, regardless of the position of the gingiva (see Figure 4-2).

Clinical Crown

The clinical crown is the portion of the tooth that is visible in the mouth. The length of the clinical crown varies during the life cycle of the tooth, depending on the level of the gingiva. This means that the clinical crown is shortest when the tooth erupts into position and becomes longer as the surrounding gingiva recedes.

Root

The root is the portion of the tooth that is normally embedded in the alveolar process and is covered with cementum.

Depending on the type of tooth, there may be one, two, or three roots. Bifurcation means division into two roots, and trifurcation means division into three roots.

The tapered end of each root tip is known as the apex. Anything that is located at the apex is referred to as apical, and anything surrounding the apex is said to be periapical.

Cervix

The cervix is the narrow area of the tooth where the crown and root meet. (Cervix means neck.)

The cementoenamel junction is formed by the enamel of the crown and the cementum of the root. This area is also known as the cervical line or the CEJ.

Tissues of the Tooth

Enamel

Enamel, which makes up the anatomic crown of the tooth, is the hardest material of the body. This hardness is important because enamel forms the protective covering for the softer underlying dentin. It also provides a strong surface for tearing, crushing, grinding, and chewing food.

Enamel is translucent and ranges in color from yellow-white to gray-white. (Translucent means that the substance allows some light to pass through it.)

Enamel is similar to bone in its hardness and mineral content. Unlike bone, mature enamel does not contain cells that are capable of repairing themselves. However, some remineralization is possible (see Chapter 17). Enamel is composed of millions of calcified enamel prisms, which are also known as enamel rods. These extend from the surface of the tooth to the dentinoenamel junction.

The enamel prisms tend to be grouped into rows that follow a course that is roughly perpendicular to the surface of the tooth.

Dentin

Dentin makes up the main portion of the tooth structure and extends almost the entire length of the tooth. It is covered by enamel on the crown and by cementum on the root.

In the primary teeth, dentin is very light yellow. In the permanent teeth, it is light yellow and somewhat transparent. The color of the dentin tends to darken as we age.

Structure of Dentin

Dentin is a mineralized tissue that is harder than bone and cementum, but not as hard as enamel. Although hard, dentin is a very porous tissue made up of microscopic canals called dentinal tubules that extend from the exterior surface, where the dentin joins the enamel or cementum, to the interior surface, which forms the pulp chamber. If the dentin is not protected by enamel, these tubules form a direct passage for invading bacteria into the pulp.

Each tubule contains a dentinal fiber that transmits pain into the pulp. Dentin is a very sensitive living tissue; therefore during dental treatment it must be protected against dehydration (excessive drying) and thermal shock (sudden temperature changes).

Because dentin is capable of some repair, when placing a restoration, the dentist can use materials that will help encourage this repair process.

Pulp

The inner aspect of the dentin forms the boundaries of the pulp chamber (Figure 4-3). Like the dentin surrounding it, the contours of the pulp chamber follow the contours of the exterior surface of the tooth.

At the time of eruption, the pulp chamber is large; however, because of the continuous deposition of dentin, it becomes smaller with age.

The portion of the pulp that lies within the crown portion of the tooth is called the coronal pulp; this includes the pulp horns, which are extensions of the pulp that project toward the cusp tips and incisal edges.

The other portion of the pulp is more apically located and is referred to as radicular or root pulp. The radicular pulp of each root is continuous with the tissues of the periapical area via an apical foramen.

In young teeth, the apical foramen is not yet fully formed, and this opening is wide. With increasing age, the pulp chamber becomes smaller.

Structure of the Pulp

The pulp is made up of blood vessels and nerves that enter the pulp chamber through the apical foramen. The blood supply is derived from branches of the dental arteries and from the periodontal ligament.

The nerves in the pulp receive and transmit pain stimuli. When the stimulus is weak, the response by the pulpal system is weak, and the interaction goes unnoticed. However, when the stimulus is great, the reaction is greater, and the patient feels pain.

Cementum

Cementum, which is not as hard as either enamel or dentin, protects the root of the tooth and joins the enamel at the CEJ. Cementum is of a light yellow shade that is somewhat lighter than the color of dentin and darker than enamel. Cementum also lacks the luster and translucent qualities of enamel.

Normally, cementum is covered by bone and gingival tissue. If it is exposed because of gingival recession and bone loss, cementum is very sensitive and susceptible to decay.

Periodontium

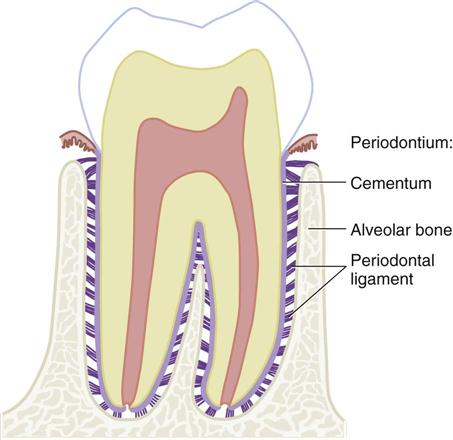

The periodontium supports the teeth in the alveolar bone. The periodontium consists of cementum, alveolar bone, and the periodontal ligaments. These tissues also protect and nourish the teeth.

Periodontal Ligament

The periodontal ligament is dense connective tissue organized into groups of fibers that connect the cementum covering the root of the tooth with the alveolar bone of the socket wall. At one end, the fibers are embedded in cementum; at the other end, they are embedded in bone. These embedded portions become mineralized and are known as Sharpey’s fibers. The periodontal ligament ranges in width from 0.1 to 0.38 mm, with the thinnest portion around the middle third of the root. As we age, a gradual progressive decrease in the width of these fibers occurs (Figure 4-4).

Types of Teeth

Humans eat a diet that includes meats, vegetables, grains, and fruit. To accommodate this variety in our diet, our teeth are designed for cutting, shearing or incising, tearing, and grinding different types of food (Table 4-1).

TABLE 4-1

| Types of Teeth | Characteristics | Functions |

| Incisors | Single-rooted teeth with a relatively sharp and thin edge. Located at the front of the mouth. | Designed to cut food without heavy force |

| Canines | Also known as cuspids, they are located at the “corner” of the dental arch. The crown is thick, with one well-developed pointed cusp. Because of their long root, canines are the most stable teeth in the mouth and are usually the last teeth to be lost. | Designed for cutting and tearing of food that requires the application of force |

| Premolars | Also known as bicuspids, they are similar to canines in that they have points and cusps. They have a broader chewing surface. There are no premolars in the primary dentition. | Designed for grasping and tearing; they also have a broader surface for chewing |

| Molars | The molars have more cusps than the other teeth in the dentition. They have shorter, blunter cusps to provide a chewing surface. | Designed for chewing and grinding solid masses of food that requires the application of heavy forces |

Dental Arches

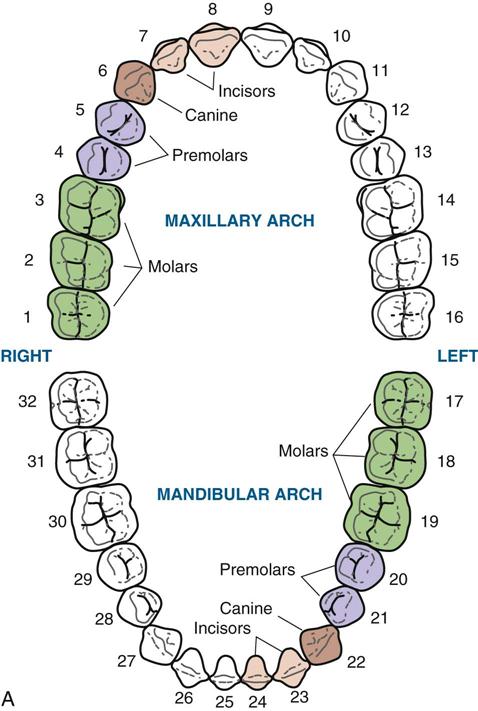

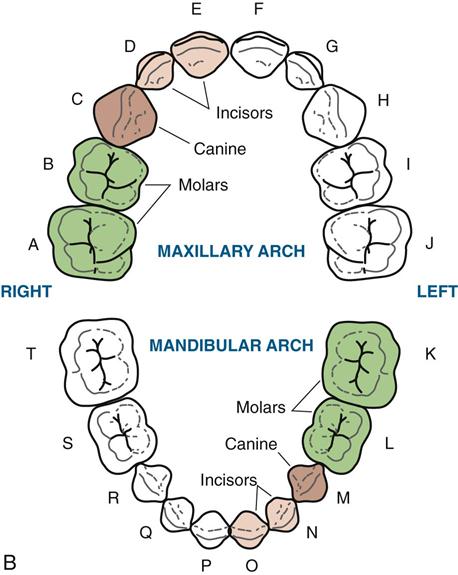

In the human mouth, there are two dental arches: the maxillary and the mandibular. The lay person may refer to the maxillary arch as the upper jaw and the mandibular arch as the lower jaw (Figure 4-5).

• The mandibular arch is capable of movement through the action of the temporomandibular joint.

• The maxillary arch, which is actually part of the skull, is fixed and is not capable of movement (see Chapter 3).

Quadrants and Sextants

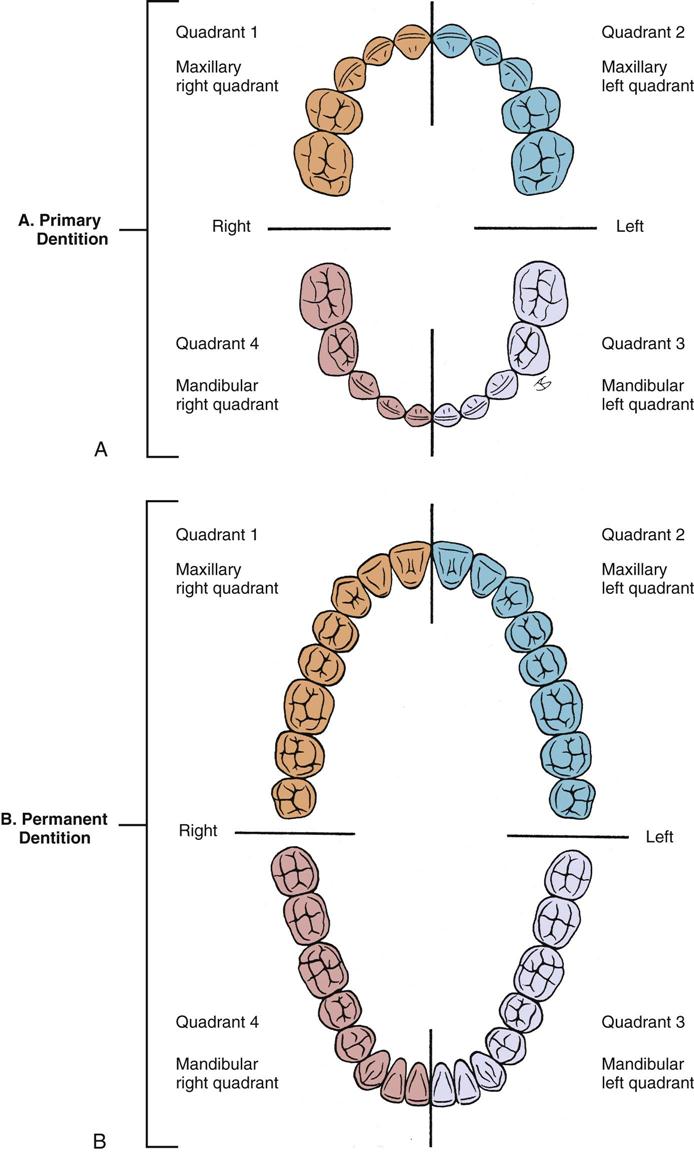

An imaginary midline divides each dental arch into mirror halves. The two arches, each divided into halves, create four sections, which are called quadrants (Figure 4-6).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses