4

Consultations

Consultations involve referring patients to another clinician or clinical service for an opinion and/or treatment concerning a specific problem.

Requesting and Answering Consultations

Triaging Consultations

Consultations (consults) should be prioritized, or “triaged,” on their degree of urgency. For example, trauma, hemorrhage, and infection, particularly in immunosuppressed patients, should be considered urgent requests for dental services and should be addressed as soon as possible. For non-acute consultation requests, an answer within 24 hours is acceptable, and a response on the same day is ideal. This might be specified in the hospital or departmental staff by-laws or policy manual.

The Different Types of Consultations

Whether seeking or responding to a consultation request, there are different types of consultations:

- Opinion only; for example:

- A cardiology consult may be requested for management assistance in a patient with extensive valvular disease at risk for infective endocarditis after an invasive dental procedure.

- A dental consult may be requested concerning the immediate need or timing for a dental treatment for a hospitalized patient.

- Opinion and treatment of a specific problem: This request is problem-specific and does not require comprehensive care for the patient.

Requesting Consults from Other Services

Standard consult request forms exist in most hospitals and should include the following information:

- Date

- Requesting service

- Service consulted

- Problem(s) to be addressed

- Questions to be answered

- Vital information of interest to consultant

- Whether you are seeking an opinion only regarding diagnosis and/or management or to transfer the patient and the provision of treatment to another consultant or service

When consulting physicians concerning the medical management of a dental patient, it is useful to include a description of the extent of the dental treatment contemplated with regard to anticipated stress, bacteremia, bleeding, and postoperative healing time. Availability, promptness, and quality often determine both the frequency of consult requests from other services and the nature of consultations.

Examples of Medical or Surgical Services

- Neurology/geriatrics for further assessment in the event of suspected dementia

- Internal medicine to assist in medical management of patients

- Anesthesiology for pre-general anesthesia assessment

- Specialist surgical services, especially for patients requiring general anesthesia to provide their dental care, but who also need other semi-elective surgical procedures under general anesthesia

- Psychiatry or psychology to assist in behavioral management issues, to address concerns regarding potential interactions with ongoing psychoactive medication regimens, and to assess suspected depressive illness

- Diabetic services to assist with diet issues and establishing appropriate glycemic control with appropriate diet control

Other Clinical Services Consulted as Dictated by the Patients’ Needs

- Physical therapy for advice regarding such issues as assistance in transferring a patient between bed, gurney, wheelchair, and dental operatory, and addressing physical rehabilitation related to temperomandibular joint dysfunction management and/or post intermaxillary fixation

- Occupational therapy to assist in the selection and fabrication of adjunctive oral health devices for patients with impairment of hands and arms

- Speech therapy for appraisal of suspected swallowing dysfunction or other oral motor function (e.g., speech, mastication). Also to assist in improving communication with an aphasic patient

- Pharmacy for advice regarding medication dose adjustments (e.g., patients with renal insufficiency/failure or liver dysfunction) and drug interactions

- Social work to assist in communicating with a patient’s family and other healthcare institutions, social services, and health financial services

- Nutrition/dietary to assist in nutritional assessment and planning and supplementation (e.g., soft diet) for newly edentulous patients

Answering Consult Requests from Other Services

Where Are You Going to Undertake Your Assessment of the Patient?

Does this examination need to take place bedside or can the patient be transferred to your department, with all the advantages of a dental chair, equipment (lights and mirrors), and access to radiographic equipment? Some patients clearly are not fit to be easily, or safely, transferred and are best seen bedside. For example:

- Patients on respiratory or neutropenic precautions

- Intubated patients, or those requiring intensive cardiopulmonary monitoring

- High-risk pregnant patients on strict bed rest

- Patients with significant physical impairment

When in doubt, examination should be conducted at the patient’s bedside. Patients should almost never be brought to the dental clinic before reviewing the medical chart and seeing them bedside to ensure that there is no risk to the patient or dental clinic staff.

Bedside Oral Examination

Ensure that you have all the necessary equipment when conducting a bedside oral examination. Most medical/surgical wards stock gloves and tongue blades, but not a good source of light (headlight or flashlight) or dental mirrors. For minors and intellectually impaired people, consider having a member of the clinical staff of the hospital as a chaperone present for your interview and examination.

Patient Transport and Escorts

For patients sufficiently healthy and mobile to be seen in your office, ensure that they are transported in a wheelchair, if appropriate, with their medical chart. Patients in wheelchairs are easier to examine and radiograph than if they are on a stretcher. Prior to their transfer, check if they have any intravenous fluids running or if they require continuous oxygen. Patients receiving medication intravenously, such as chemotherapy or antibiotics, or who are in constant need of oxygen, might require hospital transportation or a nurse escort both for transportation and for the duration of their visit to the dental clinic. This may be mandatory for patients with airways compromise, such as intermaxillary wiring or fixation.

Priority: The Patient’s Point of View

A request or problem that might seem mundane to the dentist (e.g., an ill-fitting denture, chipped front tooth) can be a major concern and source of distress to the patient, the family, or the referring physician. Such requests also provide an opportunity to perform an oral examination on a patient who might not otherwise be seen by a dentist on a regular basis.

Reviewing the Patient’s Records

The patient’s records should be reviewed thoroughly. Note significant points in the medical history and hospital course. A concise but thorough note should be written, and significant findings and recommendations might need to be discussed with the physician verbally in addition to their inclusion in the written response. Effort should be made to minimize or eliminate dental jargon or terminology to ensure that the reader fully comprehends the response (e.g., “quadrant,” “ortho,” “endo,” and “apex” mean very different things to physicians and dentists).

Avoid making recommendations that create work for the consulting physician (e.g., ordering/acquiring radiographs, oral debridement of blood clots, arranging appointments with the dental office).

Findings and treatment should be discussed with relevant members of the patient’s family, if appropriate, and with the family dentist whenever possible.

Clarify who will perform any dental treatment that proves necessary, and who will be responsible for follow-up care.

Consult Format

The first line of your entry in the record should specify the date and time, your name, your level of appointment, and your service.

- Introduction, which includes:

- Patient-identifying data

- Date of admission

- Reason for admission

- Reason for consult

- Chief complaint (CC): The concern for which the consultation was requested

- History of present illness (HPI): Brief summary of the development of the admitting diagnosis as well as the hospital course to date. The description of the complaint should include:

- Location

- Duration

- Intensity and character of the complaint

- Aggravating factors

- Treatment for the problem if any. It should be clear to the requesting clinician that the chart has been reviewed and that significant findings were taken into account in making subsequent recommendations

- Past medical history (PMH), which includes:

- Illnesses

- Hospitalizations

- Operations

- Allergies

- Medications

- Relevant laboratory investigations and any radiology/imaging reports, with dates

- Past dental history (PDH): Relevant information about previous dental treatment; for example, recent extractions and how the patient fared in terms of postoperative bleeding or delayed healing. Such information may be critical to assess the patient’s fitness to undergo invasive dental procedures

- Social history: Use of alcohol, tobacco, recreational drugs

- Family history as it relates to the medical condition or dental problem

- Vital signs, e.g., blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate, temperature, oxygen saturation

- Inspection of general state of health: General appearance, body habitus, state of nutrition, posture and gait, speech

- Findings on examination should include a head and neck and intraoral examination regardless of the reason for the consult, with cranial nerve review if indicated. Significant negative and positive findings are noted. This section is descriptive rather than diagnostic and should avoid terminology that will not be understood by all concerned (e.g., use “maxillary right first molar,” not “tooth number 3”)

- Impression or assessment: All differential diagnoses should be included in decreasing order of likelihood. Because the reader may not be familiar with the impact of specific dental disease on the patient’s medical status, elaboration of the diagnosis and the implications for medical management may be indicated

- Recommendations or suggestions: The consultant is essentially a guest of the requesting service, as the admitting physician is ultimately responsible for the patient and all treatment rendered. Hence, only recommendations or suggestions are made. No treatment is performed without discussion with the admitting doctor or responsible house officer. It is often helpful for the treating clinicians and the nursing staff to note in the patient record the date, time, duration, and venue for any planned dental treatment. It also might be appropriate to include a brief description of the significance of the problem to support the recommendations. All findings are addressed, especially the reason for the consultation

- A statement as to whether or not the patient will be followed by the dental service, followed by: consultant’s signature, consultant’s printed name, and the best way(s) to be contacted (phone/pager number)

Examples of Consultation Requests from Other Clinical Services

Most of the following examples are adapted from consults written by general practice residents in dentistry. Some material has been updated to ensure that drugs and procedures are current. These examples serve as a guide to format and to illustrate standard approaches to the evaluation and management of typical oral problems of hospitalized or medically complex patients. Note that although there are a variety of writing styles in these examples, they all address the reason for consultation.

Urgent/Acute Consultation Requests

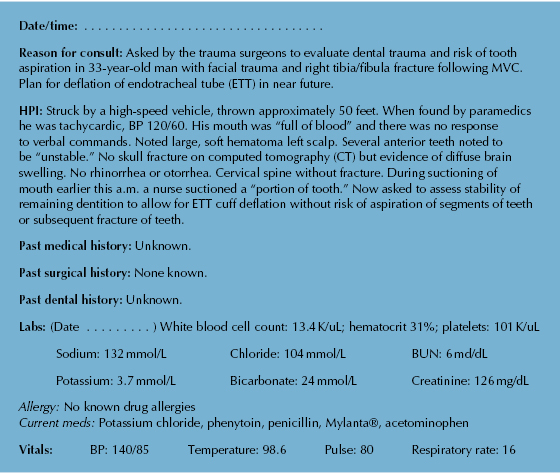

Dental Consult 1: Dental Trauma Following Motor Vehicle Collision (MVC), Risk of Aspiration

Comments

- Note that the description of the intraoral findings uses as little dental jargon as possible for the benefit of the physicians and nurses caring for this patient, but that there is a thorough baseline documentation of significant positive and negative findings.

- Significant negative findings (e.g., lack of jaw deviation, tenderness, occlusal disharmonies, mobile segments) are especially important in the evaluation of the maxillofacial trauma patient.

- The consult addresses the specific reason for the request (i.e., the safety of deflation of the ETT cuff). However, as no other clinical service has addressed the odontogenic trauma, a thorough appraisal of this region is desirable.

- Note that it was made clear that the exam was limited by the patient’s consciousness/ability to follow commands, immobilization, and body habitus, and that subsequent clinical evaluations, with radiographs, may reveal additional problems.

- Note that it was made clear in the consult that the problems were not urgent and could be addressed when the medical condition stabilizes.

- While laboratory values are used consistently in consultations, electrolytes are most important for patients who are dehydrated, especially from vomiting and diarrhea, and the BUN and creatinine are important for patients with renal disease.

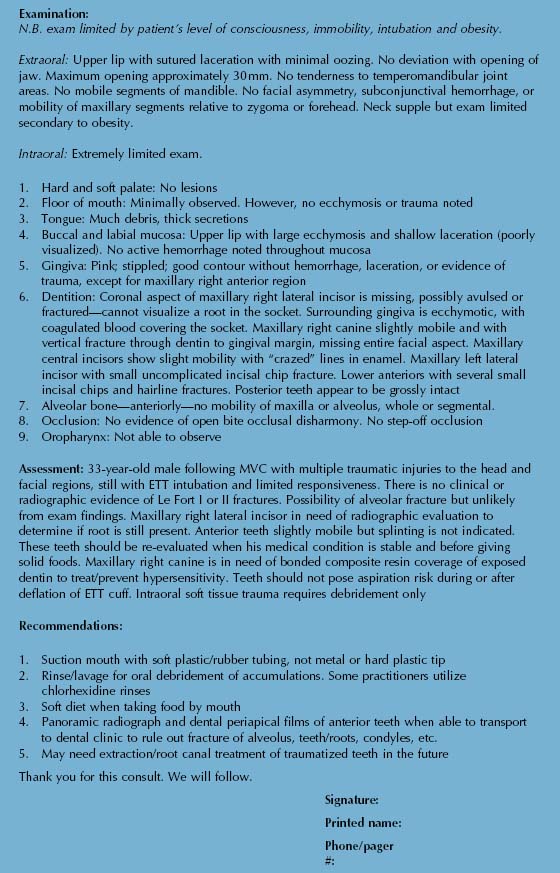

Dental Consult 2: Persistent Hemorrhage Following a Dental Extraction

| Date/time: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | ||||

| Reason for consult: Asked to see this 18-year-old male who presented two hours ago with a three-day history of intermittent bleeding after extraction of a lower molar tooth by his family dentist. No previous history of difficulties with dental extractions. | ||||

| HPI: Routine dental extraction performed three days ago because of advanced “decay,” with pain and mild facial swelling two days prior to the extraction. He had some “mild bleeding” after leaving the dental office, but two to three hours after the extraction, it “bled a lot.” He admits to spitting out blood since then. He returned to his dentist that afternoon and the socket was packed with “something” and sutures were placed, and he was advised to apply pressure with gauze. Overnight, he awoke to find pillow “coated in blood.” Bleeding slows with pressure but does not stop and every three to four hours it starts to bleed more heavily. His mother took him to their family physician, who started antibiotics and also advised to apply pressure with a sponge. He presented to the Emergency Department. BP 120/80, HR 70, temp 100°F [37.5°C]. | ||||

| PMH/PDH: As per mother and patient, no known medical problems. Denies any history of easy bruising or problems with bleeding. No previous history of any surgery, including oral surgery or previous dental extractions. Routine dental treatment in the past without problems. | ||||

| Labs: (Date . . . . . . . . . . . . ) White blood cell count 11.2 K/uL; hematocrit 53%; platelets 353 K/uL Allergy: No known drug allergies. Meds: Amoxicillin 250 mg three times per day. |

||||

| Vitals: | BP: 140/85 | Temperature: 98.6 | Pulse: 80 | Respiratory rate: 16 |

| FH/SH: Lives with parents. Mother has a history of being a “bleeder” following dental extractions, as do two of his maternal cousins. | ||||

| Examination: Extraoral: Conjunctiva, skin folds, and nail beds of normal coloration. Mild, tender, right submandibular lymphadenopathy. No trismus. Intraoral: Mild bleeding from the socket of the right mandibular first molar, with a large friable sticky clot present over the socket. 1. Hard and soft palate, buccal and labial mucosa, floor of mouth and tongue without lesions, masses, or other abnormalities

2. Some bruising evident on the buccal and lingual gingiva and alveolar mucosa adjacent to the socket; no swelling or evidence of infection

|

||||

| Assessment: 18-year-old male with persistent bleeding but without local factors (smoking, etc.) except for spitting. His presentation, along with his family history, suggests the possibility of an inheritable bleeding diathesis, such as von Willebrand’s disease. | ||||

| Recommendations:

1. Will attempt packing of socket with methyl cellulose, sutures, after attempt at hemostasis with topical thrombin

2. Gauze packing may help with tamponade

3. Admit for observation in light of persistent bleeding and concern regarding possible (but rare) bleeding into submandibular spaces and adjacent parapharyngeal spaces, with resultant risk of airway compromise

4. Suggest consultation with hematology service for investigations for possible von Willebrand’s disease and hemophilia or other coagulopathy

|

||||

| Thank you for this consult. We will follow-up with hematology as to result of investigations. | ||||

| Signature: | ||||

| Printed name: | ||||

| Phone/pager #: | ||||

Comments

- The first surgical procedure of any kind for many patients involves removal of a tooth. The nature of the post-surgical bleeding, as well as personal and family history of bleeding, help form a differential diagnosis including inherited and acquired coagulopathies. However, local measures are often the mainstay of hemorrhage control.

- Von Willebrand’s disease (vWD) is the most common congenital bleeding diathesis, and therefore is a possibility for this patient. It is an autosomal dominant disorder, associated with quantitative and qualitative deficiencies of the von Willebrand factor, which binds platelets to endothelium, as well as stabilizing the factor VIII coagulation factor.

- Patients with vWD tend to present with a mix of bleeding derangements: Constant bleeding as they fail to form a stable clot complex (vWD) and intermittent bleeding as the clot continuously turns over (absence of factor VIII).

- Patients with mild forms of vWD disease (types I and II) usually can be satisfactorily managed in the outpatient setting with preoperative infusions of desmopressin, which induces and increases factor VIII release from the endothelial cells. More severe forms, including some types that are unresponsive to desmopressin, need factor concentrate.

- Collaboration with the hematology service is vital in determining the safest means of treating the patient.

Dental Consult 3: Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia and Oral Ulcers

| Date/time: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | |||||||

| Reason for consult: Asked to evaluate oral ulcers in a 75-year-old male with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) admitted (date . . . . . . . . . .) with fever, neutropenia, and multiple oral ulcers. | |||||||

| HPI: Last summer presented with fatigue, weight loss, splenomegaly, bone marrow biopsy consistent with lymphoproliferative disorder. (Date . . . . . . . . . .): Splenectomy with improvement in symptoms and platelet count. (Date . . . . . . . . . .): Recurrence of fatigue and weight loss; white blood cell count (WBC) 200 K/uL; platelets 95 K/uL; hematocrit (HCT) 27%. (Date . . . . . . . . . .): Admitted to this hospital with bone marrow biopsy suggestive of ALL, WBC 350 K/uL. Treated with doxorubicin and prednisone with dramatic fall in WBC with anemia and neutropenia. (Date . . . . . . . . . .): WBC 4.5 K/uL, HCT 24%, platelets 2.0 K/uL. Complains mainly of fatigue and malaise. Presented to outside hospital (Date . . . . . . . . . .) for platelets (is this for an infusion?), found to be febrile to 103°F (39.4°C). Only localized complaints are multiple mouth sores. |

|||||||

| PMH: As above. Allergies: No known drug allergies. |

|||||||

| Labs: (Date . . . . . . . . . ) White blood cell count: 13.4 K/uL; hematocrit 31%; platelets: 101 K/uL | |||||||

| Sodium: 134 mmol/L | Chloride: 103 mmol/L | BUN: 37 mg/dL | |||||

| Potassium: 4.6 mmol/L | Bicarbonate: 25 mmol/L | Creatinine: 1.7 mg/dL | |||||

| Meds: Intravenous (IV) ceftazidime, tobramycin (IV), nystatin, sodium bicarbonate mouth rinses, calace, Tylenol®, Benadryl®, Mylanta®, milk of magnesia, allopurinol. | |||||||

| PDH: Last dental visit two months ago for reline of maxillary partial denture. Brushes three times/day. Regular every six-month care. History of several maxillary and mandibular root canal therapy treated teeth. Has had recent gingival bleeding but no dental abscesses. Mild herpes labialis about one/year. Upper and lower partial dentures, both three years old. | |||||||

| Vitals: | BP: 140/85 | Temperature: 98.6 | Pulse: 80 | Respiratory rate: 16 | |||

| Examination: Extraoral: Left cheek with small 1- to 1.5-cm ecchymotic area, no other lesions. No asymmetry, trismus, lymphadenopathy, tenderness to palpation. Neck supple. Intraoral: 1. Soft/hard palate: Bilaterally along inner aspect of upper alveolar ridge, patchy 2-cm by 1- cm area of “curdy” white plaques with no surrounding erythema, removed with cotton tip. Shallow, 1-cm diameter, deep, red ulcerations with debris around margins in hamular notch/tuberosity area bilaterally, without tenderness or hemorrhage. Slight erythema of soft palate. Several scattered petechiae. Small ulcerations on anterior hard palate. No evidence of secondary infection. Oropharynx: generally erythematous, without purulence or exudate

2. Tongue: Pebbly, grainy appearance to dorsum. No plaques or lesions, sight erythema

3. Lips: Thin, dry mucosa. No cracking or ulceration

4. Buccal mucosa: Right posterior buccal mucosa with large diffuse, non-raised, non-tender 3-cm by 5-cm semilunar-shaped area of ecchymosis. No break in mucosa

5. Floor of mouth: Supple, no masses, lesions, ecchymosis, or debris

6. Gingiva: Multiple large “liver clot” areas of oozing hemorrhages surrounding upper teeth. No swelling but positive for edema, erythema, and debris. Lower anterior teeth with 2- to 3- mm recession, slight debris, blunt papillae, puffy margins with slight erythema. No bleeding, swelling, or purulence.

7. Alveolar ridge: Maxilla—generalized diffuse distribution of many small, less than 1-mm, erythematous, tender ulcerations with many petechiae; mandible—retromolar pad areas with bilateral 1-cm diameter hematomas with slight ulceration

8. Dentition: All upper remaining teeth have had root canal treatment. All teeth with 1–II/III mobility. Sensitivity to percussion maxillary right premolars. Lower teeth with multiple crowns. No caries or sensitivity noted

9. Prosthesis: Upper and lower removable partial worn 24 hours/day continuously until (date . . . . . . . . . .)

10. Vestibules: Upper with generalized erythema and several small areas of ulceration

11. Salivary flow: Saliva was expressed from all ducts with grossly normal consistency

|

|||||||

| Assessment: Very pleasant 75-year-old male with fever and neutropenia, about 14 days following chemotherapy for ALL, now with several mouth problems from long-standing periodontal disease and denture use during chemotherapy. | |||||||

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses