3

Oral Medicine: A Problem-Oriented Approach

Oral medicine relates to the diagnosis and Management of a wide variety of nonsurgical and mostly nonodontogenic problems of the oral cavity and maxillofacial region, principally including oral mucosal diseases, salivary gland disorders, and orofacial pain. These problems can be subdivided into those that are local vs. those that represent oral manifestations of systemic disease and medical therapy. Early recognition may increase the likelihood for a more favorable management of a number of medical conditions. A classic example of a local disease is an oral squamous cell carcinoma, which if detected early can have a major impact on a patient’s mortality and morbidity. Similarly, systemic diseases can show characteristic oral signs and symptoms that can suggest undiagnosed or worsening disease, such as oral candidosis in HIV infection, oral ulcerations as the first signs of pemphigus vulgaris, or gingival infiltrates in undiagnosed leukemia.

The starting point in oral medicine, as in all clinical disciplines, is the history. Developing the skill—indeed the art—of taking a history that is succinct, relevant, but also comprehensive is essential. A careful history of the patient’s chief concern will often tip off an experienced clinician to the diagnosis. A classic example is the history of excruciating paroxysms of electric-like pain triggered by eating or cold air hitting the face in an elderly woman with trigeminal neuralgia. The medical history is particularly important in order to have a thorough understanding a patient’s medications (prescribed and otherwise), both from the standpoint of oral side effects of drug therapy and also from consideration of the interaction of medications prescribed to patients by different clinicians. A careful review of systems can also uncover undiagnosed problems, for example, an uncontrolled diabetic patient can present with a constellation of different symptoms ranging from frequent urination to numbness of the extremities. Eliciting both a social history of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs use and a dental history including the types of oral health products used is also of paramount importance.

The historical data collection is followed by a careful clinical examination, both extra-oral and intra-oral. Indeed, the importance of the extra-oral examination is highlighted by the discovery of asymptomatic neck lymphadenopathy in an adult with an undiagnosed oropharyngeal cancer at the tongue base that might be impossible to appreciate during the intra-oral examination. Knowledge of how to evaluate cranial nerve function, assess salivary flow, and appreciate the nuances in the varied signs of mucosal pathology is also important. The synthesis of the history and clinical findings provides the diagnostic pathway allowing the clinician to move from a differential diagnosis, following appropriate investigations, to a definitive diagnosis and a management plan.

All oral medicine problems fall under one or more subjective complaints and/or objective signs. Patients may present with one or more of the following nine symptoms (i.e., subjective indicators): altered mucosa, pain/altered sensation, xerostomia/dry mouth, malodor, slow healing, swelling, bleeding, altered oral function (opening, eating, speaking, swallowing, etc.), or problems with teeth.

Based upon the examination, patients will have at least one of the following signs (i.e., objective indicators): altered mucosa, altered sensation, altered neuromuscular function, psychiatric/psychological problems, salivary hypofunction, changes in teeth or radiographs, or other objective findings (e.g., laboratory tests or imaging). Often, but not always, these subjective indicators map to objective indicators. There is much overlap and our attempt to classify these problems is imperfect.

This chapter serves as a problem-oriented approach to the more common oral medicine problems, and the approach is a categorization of these problems based upon presenting signs and symptoms. It is not intended as a substitute for textbooks of oral medicine or oral pathology.

Altered Mucosa

Altered mucosa can be a subjective and/or objective indicator of disease. Subjectively, a patient may sense a change due to pain/burning or another altered sensation (e.g., roughness or other change in texture felt with the tongue), or visualize a change through self-examination. Patients often are concerned about a bump, spot, patch, or sore. Alternatively, the clinician may detect an asymptomatic mucosal lesion of which the patient was unaware. Objectively, altered mucosa manifests as one or more lesions. Sometimes the subjective experience of altered mucosa is not commensurate with objective findings.

- White

- Red

- Ulceration

- Exophytic changes

- Pigmented/color changes

White Lesions (or Lesions with a Predominantly White Component)

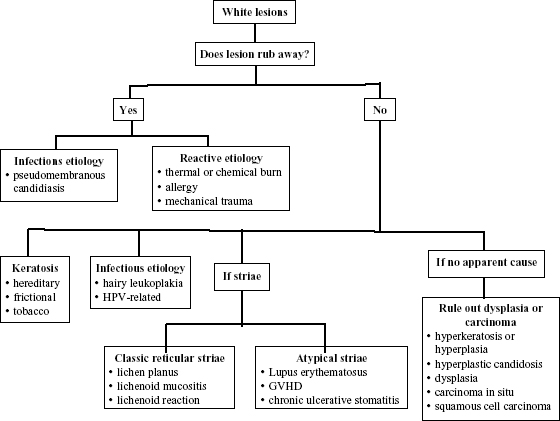

White lesions are the most commonly encountered lesions. Most are asymptomatic and generally the result of increased epithelial thickness due to trauma (i.e., hyperkeratosis and hyperplasia). The nature of white lesions is important given the malignant potential of some of them (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. White lesions or those with a predominant white component.

If the Lesion Rubs Away with Gauze

Consider pseudomembranous candidosis. Differential diagnosis includes reactive etiologies.

Pseudomembranous Candidosis

- Symptoms: Generally asymptomatic, although can cause a burning sensation

- History: Candidal infection, of any form or clinical presentation, is frequently a marker of underlying disease

- Local causes: salivary hypofunction (see section on “Dry Mouth”), use of corticosteroid inhalants, altered local oral microflora secondary to the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents

- Systemic causes: Uncontrolled diabetes, immunosuppression secondary to cytotoxic agents, high-dose corticosteroid therapy, bone marrow impairment, or HIV/AIDS

- Signs: White, curd-like plaques may be wiped away; the underlying mucosa may be erythematous

- Diagnostics: If unsure of the clinical presentation, perform smear (KOH float or PAS stain). Cultures are not generally used for diagnosis unless unresponsive to treatment

- Treatment: Identify and correct contributing etiology. Local causes must be addressed and systemic causes screened for and identified (e.g., diabetes, HIV disease). Topical antifungals (e.g., clotrimazole troches, miconazole buccal tablets) or systemic antifungals (e.g., fluconazole) can be used depending on the extent of disease and the overall systemic health (Appendix 12, Table A12-4).

Reactive Etiologies

The etiology is most likely trauma, which may be thermal (e.g., pizza burn) or chemical (e.g., aspirin burn). An acute allergic reaction to an oral care product is possible. Note: Use of alcohol-containing mouth rinses can cause asymptomatic sloughing or peeling of mucosa.

- Symptoms: Possible pain or burning, but may be asymptomatic

- History: Recent trauma or use of a new oral care product

- Signs: White sloughing tissue with or without erythema

- Diagnostics: After excluding traumatic causes, consider stopping or changing any product that might have a temporal association with the onset of the lesion

- Treatment: Re-evaluate in two weeks; consider biopsy if no resolution or if etiologic agent is identified (Appendix 4)

If the Lesion Does Not Rub Away with Gauze

If the clinical diagnosis of etiology is not apparent, a clinical diagnosis of leukoplakia should be made and epithelial dysplasia must be ruled out by biopsy/histopathology. Differential diagnosis includes keratosis (reactive or hereditary), immune-mediated conditions such as non-erosive lichen planus or a lichenoid reaction, an infectious etiology (e.g., hyperplastic candidosis or a human papillomavirus lesion), or more rarely autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

If the Lesion Is Present Since Childhood and Bilateral/Symmetrical White-Only Changes

Consider hereditary keratosis (e.g., white sponge nevus).

- Symptoms: Asymptomatic

- History: Present since childhood, other family members affected

- Signs: Often generalized, may involve extra-oral mucosal sites

- Diagnostics: Biopsy if history and examination findings are unclear

- Treatment: Reassurance to the patient of the benign nature of the condition

If on Buccal Mucosa at the Level of the Occlusal Plane and/or on the Lateral Tongue, and White Only

Consider a reactive, traumatic frictional keratosis:

- Symptoms: Asymptomatic, occasionally a mild discomfort in the presence of epithelial breakdown

- History: Cheek/tongue/lip chewing (possibly associated with anxiety)

- Signs: Often as a linea alba, but can affect any area that can be traumatized

- Diagnostics: Biopsy if etiology is unclear

- Treatment: Reassurance; consider acrylic appliance in severe cases where ulceration occurs; consider psychological source and referral

If the Patient Uses Tobacco Products and White Only

Consider smoker’s keratosis/nicotinic stomatitis or smokeless tobacco keratosis:

- Symptoms: Asymptomatic

- History: Smoker (cigarettes, cigars, pipes, etc.), smokeless tobacco (chewing, snuff, etc.)

- Signs: Prominent minor salivary gland duct openings on palate (nicotinic stomatitis); associated tobacco malodor and tooth staining; corrugated mucosa and gingival recession associated with site(s) of tobacco placement (smokeless tobacco).

- Diagnostics: Biopsy only, if features are atypical and suspicious for dysplasia/malignancy.

- Treatment: Cease tobacco use.

If the Lesion is Bilaterally on the Lateral Border of the Tongue and White Only

Consider oral hairy leukoplakia:

- Symptoms: Asymptomatic

- History: Known HIV or high-risk activity, or other underlying cause of immunosuppression

- Signs: Vertical corrugations, other oral manifestations of HIV disease may also be present (e.g., pseudomembranous or erythematous candidosis), most commonly lateral border of tongue

- Diagnostics: Generally clinical diagnosis is sufficient; biopsy plus in situ hybridization for Epstein–Barr virus; mucosal smear to confirm EBV; exclude candida

- Treatment: If unknown HIV infection, consider referral for testing (Appendix 18). If patient concerned as to appearance, consider antivirals (acyclovir or valacyclovir to manage EBV) (Appendix 12, Table A12-4, and Appendix 18).

If the Lesion Has Fingerlike or Papillary Projections

Consider benign human papillomavirus infection (e.g., viral squamous papilloma, verruca vulgaris, condyloma acuminatum, HIV-associated florid papillomatosis, focal epithelial hyperplasia):

- Symptoms: Asymptomatic

- History: Possible history of sexually transmitted disease (genital/anal warts), HIV, or high-risk activity

- Signs: May be solitary vs. multiple vs. generalized; exophytic (pedunculated or sessile), can involve lips, often has surface changes (although can be flat)

- Diagnostics: Biopsy

- Treatment: If generalized and unknown HIV infection, consider referral for testing. Excision, but if widespread and recurrent, consider topical or systemic agents (e.g., interferon)

If Lesions Show Bilateral Symmetrical and Classical Reticular Striae

Consider lichen planus, lichenoid mucositis:

- Symptoms: Depending on presence/degree of erosions or ulceration, range from asymptomatic to sensation of roughness to tongue, to sensitivity, to acidic/spicy foods, to significant pain

- History: Medications, foods/beverages, oral hygiene products, or other allergens can cause lichenoid mucositis; temporal association with the start of the lesions and the commencement of a specific medication (although not always), e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, antihypertensives, and oral hypoglycemic agents

- Clinical signs: Oral lesions may be white only, red with peripheral white changes, or ulcerated with periphery of red and white; may be skin lesions and/or possibly symptomatic genital lesions

- Diagnostics: Biopsy (of white areas); possible patch testing for allergens; direct immunofluorescence rarely useful

- Treatment: Topical or systemic corticosteroids, or calcineurin inhibitors for symptomatic or ulcerative disease (Appendix 12, Table A12-4); discontinuation of possible causative agents may help

If the Lesion is Unilateral or Asymmetric and Has Reticular Striae

Consider lichenoid reaction:

- Symptoms: Range from asymptomatic to sensitivity to spicy/acidic foods/beverages

- History: Previous dental treatment (e.g., amalgam)

- Signs: Lesions in direct contact with amalgam restorations (so-called contact or “kissing lesions”)

- Diagnostics: Biopsy and/or consider patch test for amalgam and planned replacement materials

- Treatment: Consider replacing amalgams with an alternative restorative material

If the Lesion Has Atypical Pattern or Distribution of Striae

Consider lupus erythematosus (LE), graft-verus-host disease (GVHD), or chronic ulcerative stomatitis:

- Symptoms: Sensitivity to spicy/acidic foods/beverages

- History: Long-standing presentation with or without systemic disease. For GVHD, history of allogeneic transplant

- Signs: In LE (discoid vs. systemic), oral signs usually erosive or ulcerative with annular white striae, particularly on the palate. Systemic LE (SLE) and GVHD may see extra-oral manifestations (skin and other organ involvement)

- Tests: Biopsy for both histology and direct immunofluorescence; indirect immunofluorescence or serology, especially screening for systemic lupus erythematous (ds-DNA, and Sm antibodies) or chronic ulcerative stomatitis (ANA+ in IIF)

- Treatment of oral manifestation: Topical or systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory agents (Appendix 12, Table A12-4)

If There Is No Apparent Cause

Consider leukoplakia a clinical diagnosis warranting biopsy to rule out a potentially malignant oral lesion (i.e., epithelial dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma):

- Symptoms: Generally asymptomatic. Squamous cell carcinoma can be symptomatic. High-grade dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma (advanced but sometimes early carcinomas too) can be painful

- History: May have no risk factor history vs. any type of tobacco with or without alcohol use. Poor diet; possible immunosuppression

- Signs: White only (homogeneous vs. non-homogeneous, speckled, granular, verrucous), mixed red/white (erythroleukoplakia), or mixed red/white/ulcerated. Latter mixed signs are more ominous

- Diagnostics: Incisional biopsy of most “suspicious” site(s) (red, ulcerated, or areas with positive toluidine blue staining)

- Treatment: If benign (epithelial hyperkeratosis/hyperplasia): observation; if hyperplastic candidiasis, consider underlying cause and prescribe antifungal agents (Appendix 12, Table A12-4). If dysplasia, carcinoma-in-situ: referral to appropriate clinician for management. Excision should only be performed by a surgeon who can provide definitive management. All patients with dysplasia/carcinoma must receive risk factor counseling and close surveillance

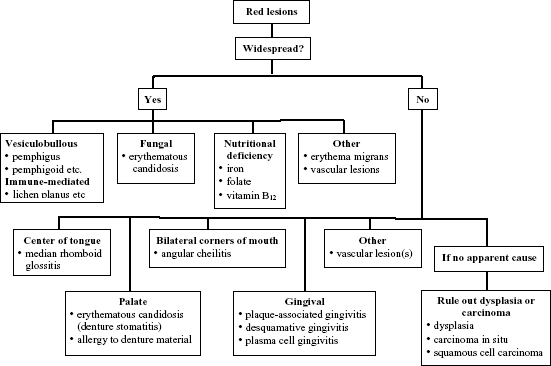

Red Lesions

Red or erythematous lesions can present with or without other mucosal changes. They are associated with increased inflammation (i.e., rubor) as the result of thin/atrophic/eroded mucosa, or because of an increase in vascularization; may be solitary, multiple, or widespread (i.e., on multiple bilateral mucosal sites); may be restricted to certain anatomic sites, e.g., the gingivae (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Red lesions or lesions with a predominant red component.

If Redness Is Widespread and Associated with Inflammatory Diseases with White and/or Ulcerative Changes

Establish the diagnosis (e.g., lesions with striae [see section on white lesions] or vesiculobullous diseases [see section on ulcerative lesions]. Note: rarely would these diagnoses show red-only changes.

If Red-Only Lesions Are Patchy and Widespread

Consider erythematous candidosis:

- Symptoms: Generally burning; may be associated with xerostomia

- History: Recent antibiotic therapy, immunosuppression, anemia, xerogenic medications (see other potential risk factors under “Pseudomembranous Candidosis” above)

- Signs: Red mucosa with possible subtle white changes that can be wiped away

- Diagnostics: Mucosal smear (KOH float or staining with PAS)

- Treatment: Antifungals (e.g., topical agents) (Appendix 12, Table A12-4).

If Redness Is Associated with Clinically Atrophic Mucosa (Especially the Tongue)

Consider nutritional deficiencies:

- Symptoms: Burning, sensitivity to hot and/or spicy foods; possible dysphagia/odynophagia; extra-oral possible fatigue, possible numbness of extremities or other neurological symptoms (vitamin B12 deficiency)

- History: Poor diet, gastrointestinal disease/gastrectomy, loss of blood (e.g., gastrointestinal or menstrual bleeding), alcoholism

- Clinical signs: Patchy erythema, associated angular cheilitis, atrophic tongue (loss of papillae), possible oral ulceration

- Diagnostics: Complete blood count (check hemoglobin and MCV); serum ferritin, folate, and vitamin B12 levels

- Treatment: Replacement therapy; investigation and correction of underlying systemic causes of deficiency state

If Redness Is Found in the Center of the Tongue Dorsum

Consider median rhomboid glossitis:

- Symptoms: Asymptomatic, sometimes burning

- History: Corticosteroid inhaler, smoking, HIV infection (or risk factors for HIV infection)

- Signs: Smooth, erythematous patch in the center of the tongue; check for erythematous “kissing” contact lesion on the palate; longstanding lesions may have overlay of white changes that cannot be wiped away

- Diagnostics: Mucosal smear if etiology in doubt

- Treatment: Identify local/systemic factors (e.g., HIV infection); Consider antifungals (Appendix 12, Table A12-4), smoking cessation

If Redness Is Restricted to the Palate and the Patient Wears a Denture

Consider denture-related stomatitis (a form of erythematous candidosis); allergy to denture material (rare):

- Symptoms: Metallic taste, possible burning

- History: Denture wearer; poorly fitting denture, poor denture hygiene (sleeping with denture in place), recent denture delivery (for allergy)

- Clinical signs: Redness maps to denture-bearing tissues (typically on palate); severe changes may show papillary surface

- Diagnostics: Mucosal smear if etiology in doubt

- Treatment: Improve denture hygiene, soaking the denture in antifungal solution, topical antifungal therapy (Appendix 12, Table A12-4)

If Redness Is Bilateral at the Corners of the Mouth (Commissures)

Consider angular cheilitis:

- Symptoms: Soreness, burning, cracking

- History: Any medical disorder predisposing patient to oral candidosis (e.g., hematinic deficiency, diabetes mellitus, HIV-infection or other immunosuppressed states); denture use; xerostomia

- Signs: If the patient uses dentures, possible reduced vertical dimension or poor denture hygiene (i.e., denture stomatitis); if no denture, possible signs of salivary hypofunction; possible fatigue (anemia) or other signs associated with possible medical disorders

- Diagnostics: Generally a clinical diagnosis. If uncertain, consider mucosal smear for candida

- Treatment: Topical antifungals (Appendix 12, Table A12-4). If unresponsive, consider combination topical antifungal/corticosteroid, or culture to rule out bacterial infection (e.g., Staphylococcal or Streptococcal). If intraoral candidosis, must treat external and internal components. If loss of vertical dimension, consider denture fabrication. If persists despite treatment, consider microbial resistance, systemic conditions, or immunocompromised states

If There Is Gingival Redness with Desquamation

Consider desquamative gingivitis (e.g., vesiculobullous diseases or lichen planus. See “Ulcerative lesions” below)

- Symptoms: Gums are red, bleed easily, or there is soreness when brushing, blisters on gums

- History: Skin diseases (e.g., lichen planus, psoriasis, vesiculobullous disorder), recent medication

- Signs: Positive Nikolsky sign (i.e., epithelium peels away when rubbed); other oral mucosal lesions and/or associated skin lesions. White reticular changes associated with redness suggest lichen planus/lichenoid mucositis reaction

- Diagnostics: If clinical doubt exists and oral hygiene is poor improve oral hygiene and re-evaluate; if suspicious of vesiculobullous disease, biopsy (away from the gingival margin), and submit for routine histology and direct immunofluorescence

- Treatment: Management depends upon diagnosis—topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors; systemic agents (Appendix 12, Table A12-4)

If There Is Gingival Redness without Desquamation, Not Plaque-Associated

Consider plasma cell gingivitis:

- Symptoms: Soreness; sensitivity to toothpastes, foods, etc.

- History: Rapid onset associated with change of habit (e.g., new toothpaste)

- Signs: Gingival changes predominate but may extend onto other surfaces

- Diagnostics: Patch test for potential allergens

- Treatment: Exclude allergen (e.g., tartar control toothpaste), possible topical corticosteroid therapy (Appendix 12, Table A12-4)

If Redness Is Not the Result of Inflammation

Consider a vascular lesion (widespread vs. localized):

- Symptoms: Generally asymptomatic

- History: Longstanding vs. recent onset (often following trauma). May be associated with certain syndromes (e.g., Sturge-Weber or Osler-Rendu-Weber)

- Signs: Flat red lesion(s) vs. exophytic red-blue lesions; localized vs. widespread and extra-oral

- Diagnosis: Diascopy (blanching upon pressure), imaging (for larger lesions), biopsy

- Treatment: No treatment for small nonprogressing lesions; surgical vs. embolization for large and progressing lesions

If No Apparent Cause for Redness

Consider erythroplakia or erythroleukoplakia (a clinical diagnosis warranting biopsy to rule out potentially malignant oral lesions [i.e., dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma]):

- Symptoms: Generally asymptomatic but may be symptomatic

- History: May have no risk factor history vs. any type of tobacco with or without alcohol use; poor diet; possible immunosuppression

- Signs: Red or red/white (erythroleukoplakia), or red/white/ulcerated; possible friability of lesion (i.e., bleeds easily)

- Diagnostics: Incisional biopsy of most “suspicious” site(s) (red, ulcerated, or areas with positive toluidine blue staining)

- Treatment: If dysplasia, carcinoma-in-situ refer to appropriate clinician for management. Excision should only be performed by a surgeon who can provide definitive treatment. All patients with dysplasia/carcinoma must receive risk factor counseling and close surveillance

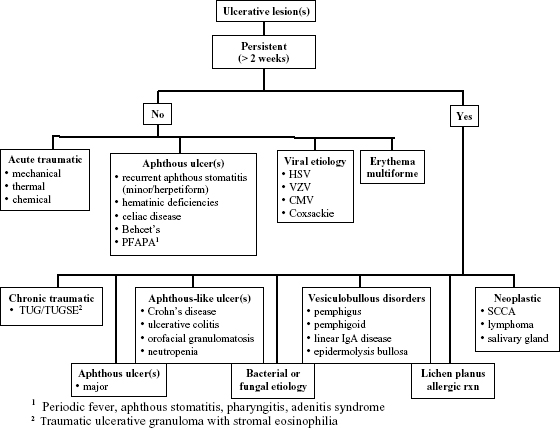

Ulcerative Lesions

Ulcers are defined as lesions devoid of epithelium. They can be short-lived vs. chronic (longer than two weeks); single occurrence vs. recurrent (i.e., episodes separated by ulcer-free intervals); superficial or deep; solitary or multiple or widespread (i.e., on multiple bilateral sites); restricted to certain anatomic sites, e.g., non-keratinized mucosa (e.g., recurrent aphthous stomatitis) vs. keratinized mucosa (e.g., gingivae or palate in the case of recurrent intra-oral herpes). May be an effect of end-organ disease or multi-organ disease processes. There is therefore a large range of potential lesions in the differential diagnosis (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. Ulcerative lesions.

If Ulcer Has Possible Traumatic Cause

Consider traumatic ulcer(s):

- Symptoms: Pain, sensitivity to foods/beverages

- History: Onset associated with a traumatic event (e.g., biting tongue, new denture); most heal within two weeks unless source of trauma not removed

- Signs: Generally single ulcer; involves sites most commonly traumatized (e.g., lateral borders of the tongue, buccal vestibule); chronic traumatic ulcer may have keratotic border (typical on tongue)

- Diagnostics: None unless ulcer persists. In cases of traumatic ulcerative granulomas (TUG) or traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia (TUGSE) a biopsy may be necessary (Figure 3.3).

- Treatment: Remove cause and follow up in two to three weeks for healing. Note: If patient has a dry mouth, consider ways to boost oral lubrication (see section on dry mouth)

If Recurrent Ulcer Involves Non-Keratinized Mucosa

Consider recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) (minor vs. herpetiform vs. major vs. complex) [may be associated with underlying systemic diseases], see Figure 3.3):

- Symptoms: Pain (moderate to severe), difficulty eating/swallowing, occasional malaise and fever (if large ulcer(s)). Positive review of systems if underlying systemic disease (e.g., fatigue if anemia; gastrointestinal symptoms if inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [e.g., Crohn’s disease, etc.])

- History: Recurrent (either long-term history vs. recent onset of recurrences); onset can be associated with trauma; frequent vs. rare recurrences; limited duration of about seven to 10 days (minor or herpetiform) or greater than one month (major); often no medical history but possible (e.g., HIV infection, anemias, cyclic neutropenia, gastrointestinal disease)

- Clinical signs: Apthae involve non-keratinized moveable mucosa. Minor apthae are round or oval, less than 10 mm in diameter, and solitary or multiple. If there are multiple, small (less than 5 mm), round, and often coalescing ulcers, consider herpetiform apthae. If the ulcers are solitary or multiple, but irregular, large (greater than 10 mm) and sometimes deep, consider major apthae. All have tan-colored necrotic centers with intense erythematous halo

- Diagnostics: None required if there is a history of infrequent idiopathic RAS (long-term history). If there is a history of frequent, worsening, or major ulcerations consider baseline complete blood count, serum ferritin, folate, and vitamin B12 levels to rule out the unusual case of hematinic deficiency, or referral for work-up of other systemic diseases associated with RAS

- Treatment: Palliative if minor RAS with infrequent recurrence (topical anesthetics vs. mucosal barriers vs. topical anti-inflammatory agents); anti-inflammatory vs. immunomodulatory agents for frequent recurrences or major RAS (Appendix 12, Table A12-4). If underlying systemic cause refer to appropriate clinician for management

If Non-Persistent Ulcers Involve Keratinized Mucosa

Consider recurrent intra-oral herpes simplex infection (HSV). Differential includes shingles (varicella zoster virus infection [VZV]):

- Symptoms: Mild discomfort

- History: Recent onset, duration seven to ten days

- Signs: Unilateral; involving hard palate or gingivae; multiple ulcers, punctate and coalescing; if following distribution of trigeminal nerve branch with possible skin involvement consider shingles (i.e., secondary VZV infection)

- Diagnostics: Generally none; if unsure consider smear, viral culture (if early disease)

- Treatment: Symptomatic; antiviral agents if severe, frequent outbreaks, or immunocompromised patient (Appendix 12, Table A12-4)

If Ulcers Are Involved with Concomitant Gastrointestinal Symptoms and/or Lip Swelling

Consider inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s). Differential includes celiac disease or orofacial granulomatosis:

- Symptoms: Oral discomfort; gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (i.e., possible diarrhea, pain, bleeding)

- History: Recurrent, often persistent ulcers until treated

- Signs: Variable, any one or combination of fluctuating lip swelling (possible in Crohn’s and orofacial granulomatosis), aphthous-like ulcerations, cobblestone mucosa, deep linear ulcerations, mucogingivitis, granulomatous angular cheilitis, vertical lip fissures, mucosal tags, pyostomatitis vegetans, concomitant pale mucosa, glossitis (from vitamin deficiency)

- Diagnostics: Biopsy (to look for granulomatous disease); endoscopic examination of GI tract (for Crohn’s disease); patch testing to a range of dietary allergens (e.g., benzoic acid or cinnamaldehyde) for orofacial granulomatosis

- Treatment for oral manifestations: Referral to gastroenterology; control of underlying disease with immunosuppressants if appropriate (Appendix 12, Table A12-4)

If Recurrent Non-Persistent Widespread Ulcers and/or Skin Target Lesions

Consider erythema multiforme:

- Symptoms: Oral discomfort

- History: Recurrent stomatitis lasting two weeks

- Clinical signs: Bloody crusting of lips, possible target lesions, especially on hands

If Persistent Ulcers Associated with Reticular Striae

Consider ulcerative lichen planus or lichenoid reaction/mucositis (see section on white lesions)

If Persistent Widespread Ulcers Not Associated with Reticular Striae

Consider autoimmune vesiculobullous disorders:

- Symptoms: Oral discomfort, difficulty eating

- History: Sudden onset; possible history of autoimmune disease; new medication

- Signs: Variable: bullae that rupture to form ulcers; may involve any mucosal site; possible skin lesions (bullae). Note: Mucosal ulcers may precede skin involvement

- Diagnostics: Biopsy for conventional histopathology and/or direct immunofluorescence; blood draw for indirect immunofluorescence or specific auto-antibodies (e.g., desmoglein 3 for pemphigus)

- Treatment: See the specific disorders, below.

Pemphigus Vulgaris

- Diagnostics: Direct or indirect immunofluorescence shows intercellular autoantibody/complement distribution (IgG/IgM and C3), positive desmoglein 3 (mucosal involvement) and/or 1 (skin involvement)

- Treatment: Systemic corticosteroids with or without steroid-sparing agents (azathioprine vs. mycophenolate mofetil) (Appendix 12, Table A12-4)

Pemphigoid (Mucous Membrane and Bullous)

- Diagnostics: Direct immunofluorescence shows autoantibody and complement distribution at basement membrane zone (IgG/IgM and C3). Referral to ophthalmologist due to potential for eye involvement (symblepharon)

- Treatment: None if mild; topical agents for mild to moderate disease; systemic agents (corticosteroids, dapsone, and other immunosuppressant agents) (Appendix 12, Table A12-4)

Linear IgA Disease

- Diagnostics: Direct immunofluorescence shows autoantibody distribution at basement membrane zone (IgA)

- Treatment: Topical or systemic agents (Appendix 12, Table A12-4)

Epidermolysis Bullosa

- Diagnostics: Direct immunofluorescence shows autoantibody and complement distribution at basement membrane zone (IgG/IgM and C3) (antibodies to collagen); genetic testing

- Treatment or oral manifestations: Depends on severity—topical vs. systemic agents (Appendix 12, Table A12-4)

If Solitary Ulcer with No Obvious Cause and Persistent (Greater Than Two Weeks)

Rule out squamous cell carcinoma or other malignancy (e.g., lymphoma, salivary gland malignancy). Other entities in differential diagnosis include traumatic ulcerative granuloma (TUG) (with or without stromal eosinophilia; TUGSE), major aphthous ulcer, necrotizing sialometaplasia, neutropenic ulcer, bacterial infection (e.g., tuberculosis or syphilis), deep fungal infection (histoplasmosis, aspergillosis, mucormycosis, etc.), or viral infection (e.g., cytomegalovirus):

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses