4 Bacterial, Viral, Fungal, and Other Infectious Conditions

Actinomycosis

Clinical Findings

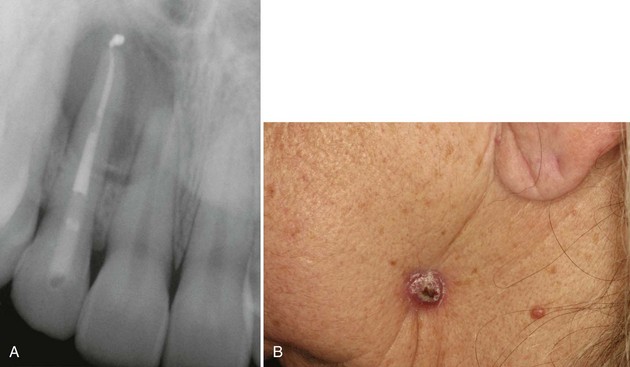

• Actinomycosis most often manifests as a periapical radiolucency, painful or painless, in a root canal–treated or grossly carious tooth (Fig. 4-1, A); it may also be associated with impacted teeth, periodontitis, or around dental implants; 80% of cases are asymptomatic; approximately 20% involve the soft tissues only; mandibular tooth infection may lead to cutaneous fistula (see Fig. 4-1, B).

• Sinus tract (known as gingival parulis) and suppuration are always present; yellowish “sulfur granules” representing masses of bacteria may be noted during biopsy.

• Presence of actinomycetes colonies in the absence of actinomycotic infection may predispose patients to obstructive tonsillar hypertrophy.

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

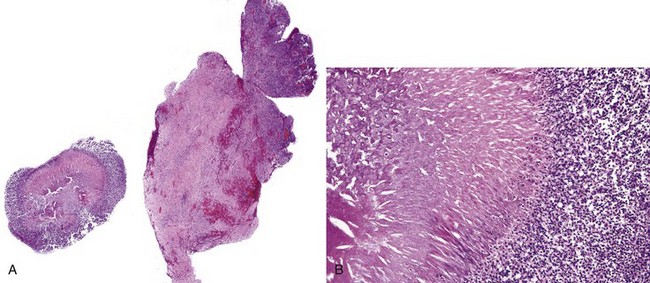

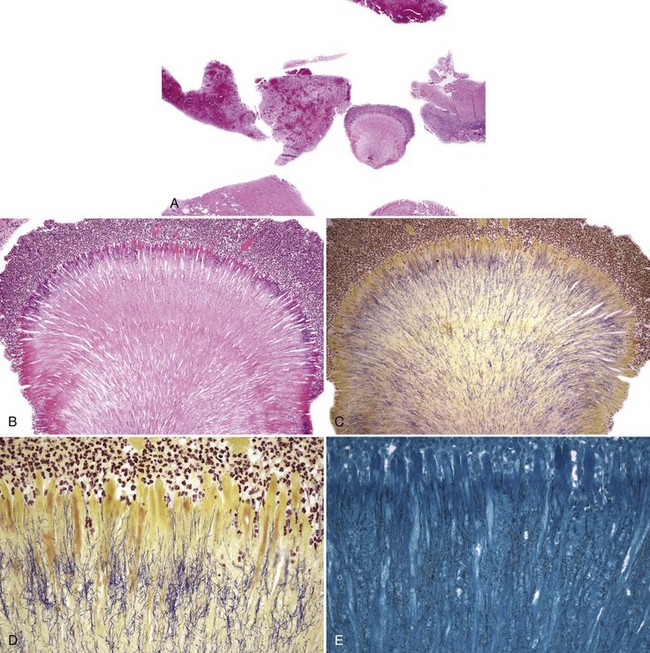

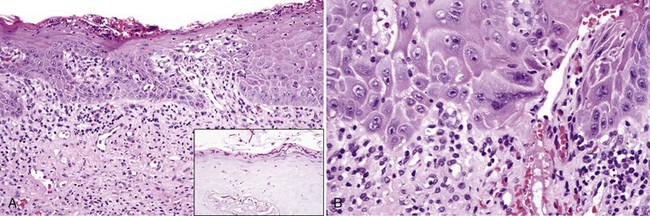

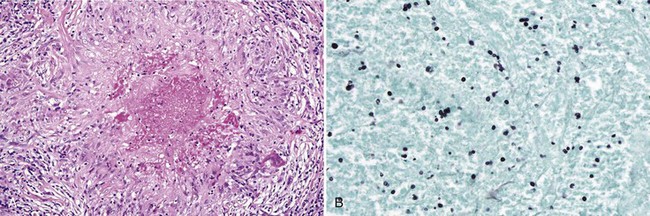

• Abundant granulation tissue with abscesses, chronic inflammation; masses of sulfur granules are composed of a round-to-ovoid masses of filamentous bacteria with a peripheral eosinophilic rim often with eosinophilic radiating “clubs” or fringe and clinging neutrophils (Figs. 4-2, 4-3, A-C); bacteria gram-positive and argyrophilic (see Fig. 4-3, D, E); concomitant apical radicular or dentigerous cyst or periapical granuloma often present

• Clumps of actinomycetes alone without the eosinophilic fringe not sufficient for the diagnosis (see later)

Differential Diagnosis

• Actinomycotic colonies are a common component of dental plaque and do not represent actinomycosis in the absence of suppuration and clinical signs (see Chapter 7).

• Masses of actinomycotic organisms are often found on the surface of exposed bony sequestra, especially in bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws (see Chapter 16).

Aldred MJ, Talacko AA. Periapical actinomycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96:386.

Brook I. Actinomycosis: diagnosis and management. South Med J. 2008;101:1019-1023.

Kaplan I, Anavi K, Anavi Y, et al. The clinical spectrum of Actinomyces-associated lesions of the oral mucosa and jawbones: correlations with histomorphometric analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:738-746.

LeCorn DW, Vertucci FJ, Rojas MF, et al. In vitro activity of amoxicillin, clindamycin, doxycycline, metronidazole, and moxifloxacin against oral Actinomyces. J Endod. 2007;33:557-560.

Ozgursoy OB, Kemal O, Saatci MR, Tulunay O. Actinomycosis in the etiology of recurrent tonsillitis and obstructive tonsillar hypertrophy: answer from a histopathologic point of view. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37:865-869.

Tang G, Samaranayake LP, Yip HK, et al. Direct detection of Actinomyces spp. from infected root canals in a Chinese population: a study using PCR-based, oligonucleotide-DNA hybridization technique. J Dent. 2003;31:559-568.

Xia T, Baumgartner JC. Occurrence of Actinomyces in infections of endodontic origin. J Endod. 2003;29:549-552.

Candidiasis (Candidosis)

This is the most common fungal infection in the mouth.

Clinical Findings

• Thrush or pseudomembranous candidiasis: curdy white papules and plaques that may or may not wipe off; usually sore or sensitive and has erythematous areas (Fig. 4-4, A and B)

• Erythematous candidiasis: sensitive erythematous area often outlined by the shape of a denture; also as linear erythematous gingivitis in patients with HIV/AIDS (see Fig. 4-4, C and D)

• Angular cheilitis: pain, cracking, fissuring, and maceration of corners of mouth (usually bilateral); seen in denture wearers where dentures do not adequately support soft tissues; also in vitamin B12 and iron deficiencies (see Fig. 4-4, E)

• Hyperplastic candidiasis: white plaques seen in mucocutaneous disease, endocrinopathies, and immunosuppression; common on the commissures bilaterally; often associated with hairy leukoplakia (see later)

• Median rhomboid glossitis: erythematous, ovoid, or rhomboid raised area of the midline dorsum of tongue anterior to the circumvallate papillae (see Fig. 4-4, F)

• Candidiasis on the tongue dorsum: often associated with concomitant “kissing” lesions on the palate (see Fig. 4-4, G and H)

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

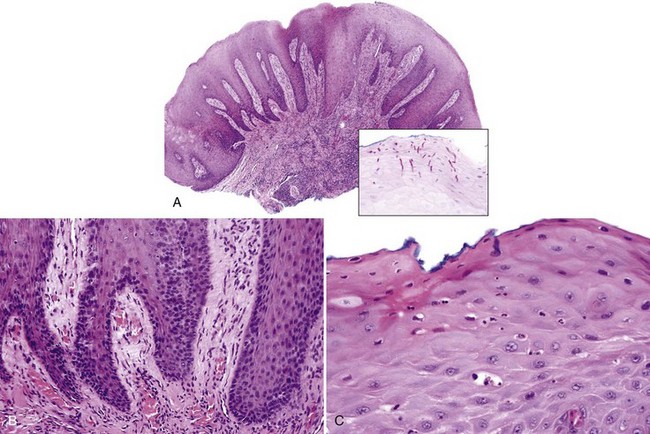

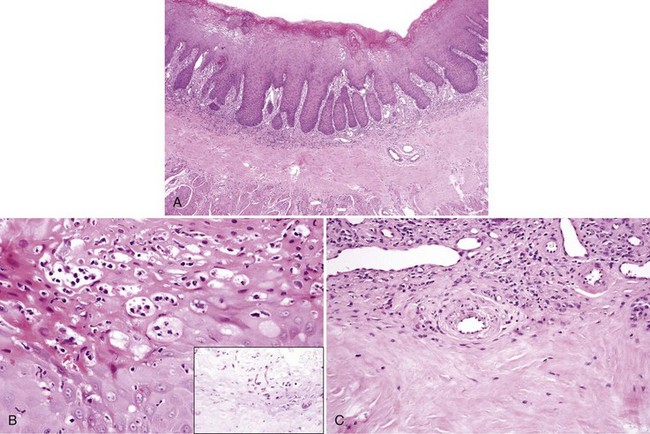

• Epithelial hyperplasia (often psoriasiform) with parakeratosis, neutrophilic exocytosis and spongiotic pustules, reactive epithelial atypia, vascular ectasia, and variable lymphocytic infiltrates (Fig. 4-5, A-C); candidal hyphae and/or conidia seen in the periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain with diastase digestion or methenamine silver stain (see Fig. 4-5, A inset); possible epithelial atrophy noted (Fig. 4-6)

• Median rhomboid glossitis: loss of filiform papillae and presence of median raphe, normal hyalinized band in the midline of tongue, sometimes misdiagnosed as amyloid deposition (Fig. 4-7)

Differential Diagnosis

• Epithelial dysplasia with secondary candidiasis exhibits significant epithelial atypia and may be difficult to differentiate from candidiasis with reactive atypia (see Fig. 4-6, B); however, effective treatment completely resolves candidiasis without dysplasia.

• Spongiotic pustules are also seen in:

• Geotrichum candidum (causing geotrichosis) form short septate hyphae.

Akpan A, Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:455-459.

Bonifaz A, Vazquez-Gonzalez D, Macias B, et al. Oral geotrichosis: report of 12 cases. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:477-483.

Dias AP, Samaranayake LP. Clinical, microbiological and ultrastructural features of angular cheilitis lesions in Southern Chinese. Oral Dis. 1995;1:43-48.

Pienaar ED, Young T, Holmes H. Interventions for the prevention and management of oropharyngeal candidiasis associated with HIV infection in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;11:CD003940.

Sitheeque MA, Samaranayake LP. Chronic hyperplastic candidosis/candidiasis (candidal leukoplakia). Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:253-267.

Wright BA. Median rhomboid glossitis: not a misnomer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;46:806-814.

Infectious Granulomatous Inflammation

Clinical Findings

• Concomitant systemic or skin involvement is usually noted and history is very important in the diagnosis.

• Ulcerated and indurated, granular, vegetating nodules of the palate and gingiva are common oral presentations, and there is usually concomitant lung, nodal, and skin disease; immunocompromised patients are particularly susceptible to disseminated disease.

• Coccidioidomycosis caused by Coccidioides immitis is endemic in California and the southwest United States.

• Histoplasmosis caused by Histoplasma capsulatum is endemic to the Ohio-Mississippi Valley and is found in the soil and in bird and bat droppings; patients taking tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors are prone to contracting this infection, as well as coccidioidomycosis in endemic areas.

• Paracoccidioidomycosis caused by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, a soil saprophyte, is common in South America where 80% to 90% of cases are chronic (Fig. 4-8).

• Phycomycoses (order Mucorales, genera Rhizopus, Absidia, Mucor, and Rhizomucor) and aspergillosis (Aspergillus fumigatum or A. flavus) appear black, necrotic and/or fungating, resembling malignancy; rhinocerebral phycomycosis is increasing in frequency and is often seen in patients with diabetes (especially if ketoacidotic), neutropenia, malignancy, and post–organ transplantation; mortality rate is 60% to 90%; aspergillosis appears similar but tends to affect immunocompromised patients (such as those with leukemia) rather than those with diabetes; both primarily affect the palate and maxilla, and vascular involvement leads to necrosis.

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

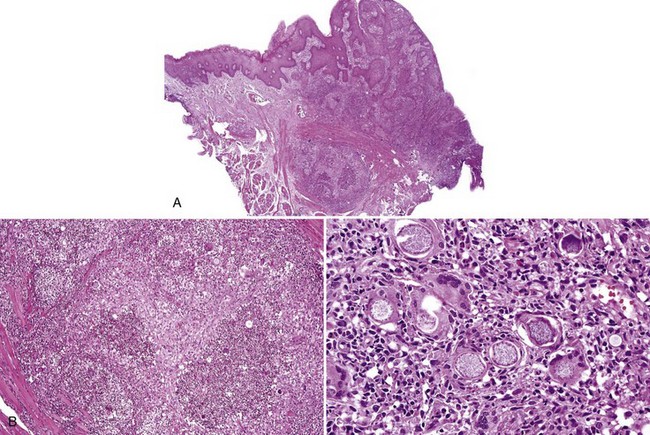

• Coccidioidomycosis: pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulomatous inflammation and budding organisms (Fig. 4-9)

• Histoplasmosis is a granulomatous inflammation, sometimes with necrosis (Fig. 4-10).

• Zygomycosis is a necrotic lesion with hyphal forms invading blood vessels; ribbon-like organisms, with right-angle branching (Fig. 4-11) are evident.

• Aspergillosis is similar to zygomycosis but organisms are slender and show acute-angle branching (Fig. 4-12); must be differentiated from mycetoma or “fungus ball” within the sinus that does not invade the soft tissues (Fig. 4-13).

• Identification of the organism using immunohistochemical stains; correlation with the clinical presentation, serology, and other tests are crucial if no organisms are found.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses