chapter 31 Armamentarium, Drugs, and Techniques

This chapter presents an overview of the equipment, drugs, and techniques that are important to the success of general anesthesia. Many of the drugs discussed have been reviewed in depth elsewhere in this book and receive only brief mention here. Other drugs are mentioned for the first time; however, their pharmacology is also reviewed briefly because it is not the purpose of this chapter to provide the reader with a belief that he or she is able to use these drugs safely after having read about them. As discussed in Chapter 30, this section is meant as an introduction to the vast subject of general anesthesia, not as a complete text in that area.

ARMAMENTARIUM

The armamentarium for general anesthesia may be divided into the following five groups:

Anesthesia Machine

The anesthesia machine is able to deliver oxygen (O2) and inhalation anesthetics to the patient. The inhalation sedation unit used in dentistry to deliver nitrous oxide-oxygen (N2O-O2) is a modification of the anesthesia machine used in the operating room. The primary difference between the two is the number of inhalation anesthetics that the operating room unit is capable of delivering. As seen in Figure 31-1, the anesthesia machine can deliver many gases: N2O, O2, sevoflurane, desflurane, and isoflurane. Flowmeters and devices called vaporizers that contain the various volatile anesthetics and permit their concentrations to be controlled are integral parts of the anesthesia machine.

During TIVA general anesthesia, an inhalation sedation unit, as discussed in Chapter 14, is used to supplement the patient’s ventilation with O2 and perhaps N2O. In the other forms of anesthesia, a unit similar to that shown in Figure 31-1 is used.

The modern anesthesia machine also contains a number of important devices for monitoring patients receiving these agents. Attached to the anesthesia machine shown in Figure 31-1 are a number of monitors, including a blood pressure monitor, electrocardiograph (ECG), pulse oximeter, capnograph (end-tidal carbon dioxide [ETCO2] monitor), and a bispectral (BIS) electroencephalograph (EEG) monitor. Attached to the right side of the unit is a ventilator, a device used to control or assist the ventilation of a patient during anesthesia.

Ancillary Anesthesia Equipment

The following items must also be available whenever general anesthesia is administered:

Face Masks

Face masks (Figure 31-2) are rubber or silicone masks that cover both the mouth and nose of the patient. Face masks are used to deliver O2, N2O-O2, and/or other inhalation anesthetics before, during, and after the anesthetic procedure. Because of the variations in the size and shape of faces, several different sizes of full-face masks should always be available.

Laryngoscopes

The laryngoscope (Figure 31-3) is a device designed to assist in the visualization of the trachea during intubation. It consists of two parts: a handle and battery holder and a blade. The handle is usually made of metal (although some are made of plastic) and contains batteries that are used to operate the light bulb found in the blade.

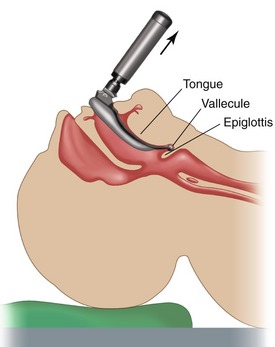

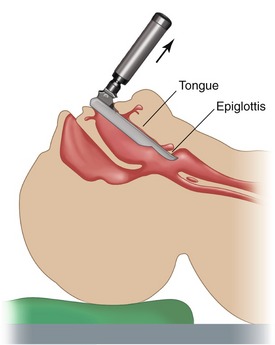

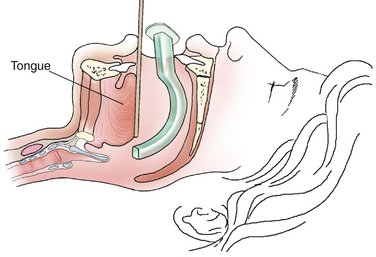

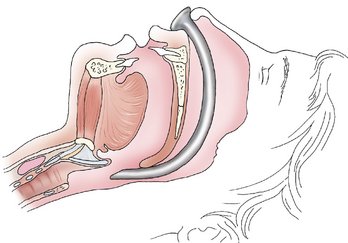

The Macintosh blade is more commonly used. The tip of the curved blade is inserted into the vallecula, the cul-de-sac between the base of the tongue and the epiglottis (Figure 31-4). The handle of the laryngoscope is then lifted straight up and slightly forward, a movement that visualizes the vocal cords. When a straight blade is used, its tip is placed underneath the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis (Figure 31-5), and the larynx is exposed by an upward and forward lift of the blade.

Endotracheal Tubes and Connectors

Endotracheal tubes and connectors (Figure 31-6) are rubber tubes designed to be placed from the mouth (oroendotracheal) or nose (nasoendotracheal) into the patient’s trachea. Reusable and disposable endotracheal tubes are available, with disposables more popular today. Because the diameter of the laryngeal opening and the trachea varies from patient to patient, endotracheal tubes are manufactured in a variety of diameters. Endotracheal tubes are commonly referred to by their size (e.g., a No. 38 tube has an external diameter of 38 mm). For adult patients, a No. 36 tube is usually appropriate for an adult male and a No. 34 tube for an adult woman. Smaller and larger tubes are available to accommodate the child or larger patient.

Endotracheal tubes normally have an inflatable cuff (see Figure 31-6, A) located near their distal ends. When a patient is intubated, the endotracheal tube is inserted into the trachea so that the uninflated cuff disappears just beyond the level of the larynx. Air is then injected into a tube that connects with the cuff to inflate it. Enough air is injected into the cuff to seal the trachea off from the pharynx, thereby preventing foreign material, such as blood, saliva, or vomitus, from entering the trachea and bronchi.

Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA)

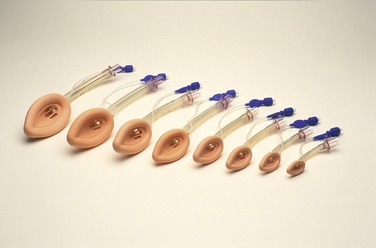

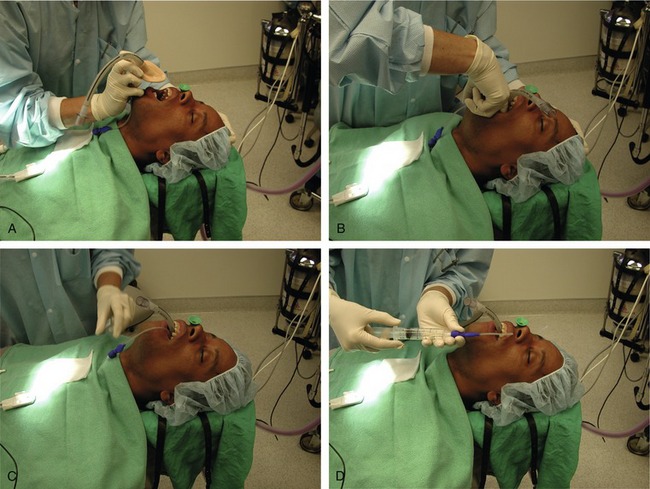

LMAs are available in seven sizes (neonate; infant; young children; older children; and small, normal, and large adult) (Figure 31-7). The LMA is inserted with the tip of the cuff pressed upward against the hard palate by the index finger while the middle finger opens the mouth (Figure 31-8, A). The LMA is pressed backward in a smooth movement (using the opposite hand to extend the airway) (Figure 31-8, B). The LMA is advanced until definite resistance is felt (Figure 31-8, C), and before the index finger is removed, the opposite hand presses down on the LMA to prevent dislodgment during removal of the index finger (Figure 31-8, D). Following removal of the finger, the cuff is inflated with air.

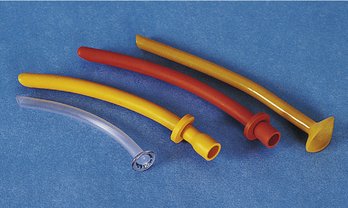

Oropharyngeal and Nasopharyngeal Airways

Oropharyngeal (Figure 31-10) and nasopharyngeal airways (Figure 31-11) are used to assist in maintaining a patent airway during and after the anesthetic procedure. Oropharyngeal airways are plastic, rubber, or metallic devices designed to lie between the base of the tongue and the posterior pharyngeal wall (Figure 31-12). The nasopharyngeal airway (also known as a nasal trumpet) is a thin, flexible rubber tube designed to be inserted through the nares and to rest between the base of the tongue and posterior pharynx (Figure 31-13). The purpose of both of these devices is to displace the tongue from the pharynx and thereby permit the patient to exchange air either around or through the airway. The nasopharyngeal airway is better tolerated by the conscious or sedated patient, thereby minimizing the occurrence of gagging and vomiting. Nasal airways should be lubricated before their insertion to rase their placement.

Figure 31-10 Oropharyngeal airways are available in a variety of sizes.

(Courtesy Sedation Resource, One Oak, Tex.)

Figure 31-11 Nasopharyngeal airways.

(From McSwain N: The basic EMT: Comprehensive prehospital care, ed 2, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.)

Magill Intubation Forceps

A Magill intubation forceps (Figure 31-14) is designed to assist in placing the endotracheal tube. It is most frequently used during nasoendotracheal intubation and is therefore a very important item in the armamentarium for general anesthesia for dental procedures.

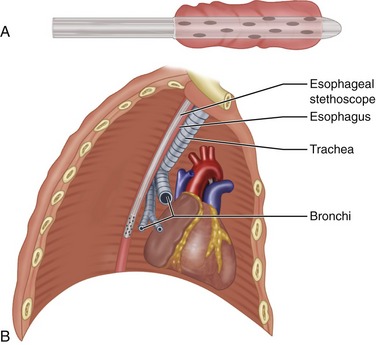

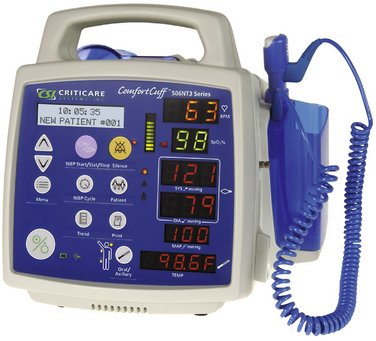

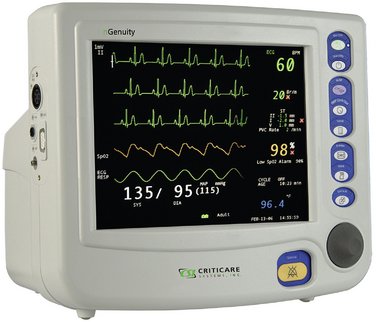

Monitoring Equipment

Monitoring of the patient during sedation or general anesthesia is essential to the overall safety of the procedure. During sedation procedures, monitoring of the central nervous system (CNS) via direct communication with the patient is of primary importance. Because the patient is able to respond appropriately to verbal command, other, more complex monitoring devices need not be used routinely.1 However, once consciousness is lost (increased CNS depression), patients are unable to respond to command, and other means of determining their status during anesthesia must be used. For this reason, the level of monitoring during general anesthesia is greater than that required for sedative procedures. A monitor is a device that reminds and warns. The Department of Anesthesiology at the Harvard University School of Medicine has designed monitoring guidelines for use during general anesthesia.2 The recommendations in these guidelines have been well received and widely implemented. The following are some of the methods and devices used to monitor patients during general anesthesia:

Figure 31-9 LMA and mouth prop. Notice LMA does not interfere with dental treatment.

(Courtesy Drs. H. William Gottschalk and Kenneth Lee.)

Emergency Equipment and Drugs

Complications occur during the administration of general anesthesia. Among the more frequently observed complications are hypotension and cardiac dysrhythmias. Monitoring of the anesthetized patient enables the entire anesthesia team to be aware of the presence of these and other potentially lethal problems and to initiate appropriate corrective treatment. The anesthesiologist will have available a supply of emergency drugs and equipment for use in these circumstances. The emergency drugs required by the board of dental examiners in the state of California4 for dentists using general anesthesia are listed here. Suggested emergency drugs and equipment from the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons may be found in Box 33-2.5 A more thorough discussion of emergency drugs recommended for outpatient facilities is presented in Chapter 33.

Emergency Drugs and Equipment Required for General Anesthesia—California

Equipment

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses