Chapter 3

Working Together

Aim

This chapter aims to guide the practitioner through their role as the team leader and how they can effectively utilise the dental hygienist in the non-surgical management of periodontal diseases.

Outcome

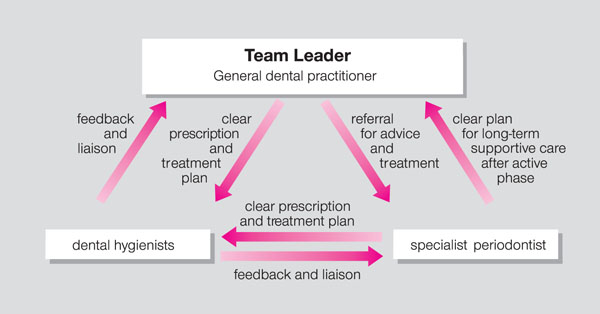

Having read this chapter the practitioner should be able to rationalise the key roles of himself or herself (Fig 3-1), the specialist periodontist, the dental hygienist and the patient in achieving a successful therapeutic outcome, and the factors influencing this such as:

-

the opportunistic aggressive nature of the disease

-

complicating systemic and local risk factors (see Chapple and Gilbert 2002)

-

patient understanding and compliance

-

operator expertise and time management

-

limiting socioeconomic factors

-

rigour of the supportive care (maintenance) programme.

Fig 3-1 The general dental practitioner as the team leader.

Introduction

The first step in successful management of periodontal disease is to establish a diagnosis and formulate an appropriate treatment plan. This is the dentist’s legal responsibility. The evidence for recording the prevalence of periodontal diseases in patients managed in general dental practice in the UK is currently very disappointing. In a study by Morgan in 2001, who examined 464 clinical records, only 20% included periodontal screening and only 1.5% (7 cases) had some form of periodontal charting – yet the cost of periodontal care to the National Health Service per annum is over £174 million (DPB website 2002). Does this imply that:

-

Treatment is carried out without a diagnosis?

-

Screening is not routinely performed in practice?

-

Screening and periodontal examination are not recorded in practice?

These data suggest that current expenditure on periodontal therapy under the NHS service regulations may not be justified by the evidence documented in the clinical notes.

Only by screening and recording each and every patient at every examination and recall appointment will the periodontal needs of the population be identified and treatment targeted at patients of “high risk”. It is inappropriate to prescribe for the patient a “routine scale and polish” every six months. The patient requires an individual care plan specifically to target sites of recurrent disease. The background to this concept is clearly outlined in the first book of this series (Chapple and Gilbert 2002).

Where there is no evidence of disease then no treatment is required. This may reflect on the entire mouth or individual teeth. The concept of selective scaling and selective root surface debridement (RSD) according to need must be established. This shift of emphasis must be explained to the patient (Chapter 5).

The practitioner must also be mindful of potential litigation. Currently, claims for failure to diagnose and treat periodontal disease amount to 4% of total claims, according to the Dental Defence Union (2001–2002). The number of claims is increasing, as is the average cost of settlement by defence organisations. Patients who have lost their natural dentition through proven negligence on the part of a practitioner now expect settlements to cover the provision of implants and their superstructures at enormous cost to the defence agencies and thus to the profession.

There is legal recognition of “the chance for a chance”. It is not good practice for the practitioner to assume that the patient is not interested in treatment because their oral hygiene has been neglected previously. All treatment options should be discussed. If the patient chooses not to follow the advice they should be informed of the potential consequences and a record of the discussion made in the patient’s clinical notes. It is good practice to utilise “practice produced” patient information leaflets. These may be given to the patient as supplementary information and evidence of this fact should be recorded in the clinical notes (Fig 3-2).

Fig 3-2 Patient information leaflets.

The Periodontal Treatment Plan and Referral to a Dental Hygienist

Details of the basic periodontal examination (BPE) and a comprehensive account of the initial screening visit is covered in the first book of this series (Chapple and Gilbert 2002). Following the BPE screen, any sextant coding 4 or 4* will require detailed recording of probing pocket depths. Recording of bleeding on blunt probing also forms part of the clinical assessment. Good quality radiographs to assess the degree and pattern of bone loss are also essential (see Chapple and Gilbert 2002). It is the responsibility of the dentist to inform the patient of the diagnosis and prognosis and discuss all treatment options. Where disease is advanced this may include extractions and eventual prosthetic replacement. If the documentation of potential outcomes is robust (i.e. percentage of bone loss is recorded), it not only avoids potential litigation but it also provides valuable information for other team members. The dental hygienist should have the radiographs on view when treating the patient. Patients frequently ask the hygienist questions regarding the prognosis of their dentition. It is not within the remit of the hygienist to make such statements, but if outcomes are written in the care plan, the hygienist can endorse and support the decisions of the prescribing dentist. This consolidates the team approach.

Communication Within the Team

A common concern expressed by dental hygienists working in general dental practice is that they feel isolated (Fig 3-3). Whilst the nature of their clinical work will always be within the legal framework, it is helpful for them to understand the holistic management of the patient, i.e. where the care they are providing juxtaposes with the care that other clinicians are providing. This helps the hygienist focus the patient on longer-term goals.

Fig 3-3 Isolation of the dental hygienist.

Good communication is therefore important, both to provide fulfilment to the staff in the workplace and to avoid errors and ambiguity in the prescribing process.

Accurate objective records of the patient’s periodontal status at the onset of therapy and throughout treatment are essential. This is achieved by using recognised charts and indices. Indices are vital for:

-

the education of the patient and for individual target setting

-

information for clinicians to determine entry into more complex therapies

-

medicolegal purposes.

Terms such as “good”, “fair”, or “poor” relating to the patient’s plaque control are not acceptable as they are not objective methods of expressing factual information between professionals. Plaque accumulation and marginal (immediate) bleeding should be recorded using a reproducible scoring system (see Chapple and Gilbert 2002). The location of plaque deposits can only be scored accurately if the plaque is visible to the clinician. The use of a disclosing dye is therefore recommended (Fig 3-4).

Fig 3-4 The use of disclosing dye to visualise plaque.

There are advantages and disadvantages with the use of various indices. Whichever is selected should be uniformly used by all clinicians in the practice to facilitate case discussion and record transfer. History of tobacco use by the patient should also be recorded in the notes at the initial stage, along with any advice given.

The Dentist as a Prescriber of Treatment

When presenting the treatment plan to the patient, care should be taken to give equal emphasis to the importance of all aspects of oral health care. For example, phrases such as “you just need a scale” or “only a quick clean up with the hygienist” imply lesser importance of periodontal health, relative to restorative needs. They also undermine the skills of the hygienist and may give the patient the impression that deposit removal is only for improvement in aesthetics. At the initial appointment the practitioner should discuss the involvement of the hygienist in the care plan and advise the patient of the advantages of referral. Case discussion between clinicians in the presence of the patient is very worthwhile. This establishes a “trialogue” in which the patient becomes informed and involved in their care plan (Fig 3-5). In particular, this is helpful at the initial appointment when the treatment plan is being discussed with the patient. If the dentist introduces the dental hygienist to the patient at this stage, it may help to overcome the patient’s initial reluctance to see another clinician. This continuity may help to foster the professional />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses