chapter 3 The Spectrum of Pain and Anxiety Control

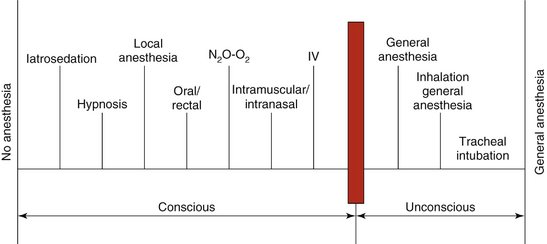

A variety of techniques are available to dental and medical professionals to aid their management of a patient’s fears and anxieties regarding dental care and surgery. To some this statement may be self-evident; however, to others the availability of a variety of techniques may come as something of a surprise. The aim of this chapter is to introduce the concept of the spectrum of pain and anxiety control. This spectrum, which is presented graphically in Figure 3-1, demonstrates that there are indeed quite a number of techniques available to manage patients’ fears and anxieties. This chapter introduces the various techniques included in this spectrum, and subsequent chapters and sections describe them in depth.

The vertical bar about three quarters of the way across the spectrum in Figure 3-1 denotes a very significant barrier: the point at which consciousness is lost. Techniques to the right of the bar fall under the heading of general anesthesia, whereas techniques to its left may be termed psychosedation, sedation, conscious sedation, or as recently redefined: minimum, moderate, or deep sedation.1–3

The bar representing the point at which unconsciousness occurs is significant in that it identifies a level of training that must be achieved by the dentist before various techniques can even be considered for use. Without elaborating at this point (educational requirements for specific techniques are discussed in the appropriate sections of this book), it may be stated that the absolute minimum of training recommended for the use of general anesthesia is 2 full years in an accredited residency program. These guidelines for general anesthesia and those for techniques of sedation have been accepted by the American Dental Association, the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology, and the American Dental Education Association.2,3

The duration of time required to adequately prepare the dentist to use the various techniques of sedation safely and effectively will vary from technique to technique and from dentist to dentist. Many dentists and dental hygienists are fully prepared upon graduating from dental school to enter into private practice knowledgeable in the safe and effective use of some of these techniques. Many others, however, will not have obtained this ability, and for these health care professionals, continuing education courses are available.4 In the United States for inhalation sedation with nitrous oxide (N2O) and oxygen (O2), a minimum course of 14 hours, including patient management, is recommended; for intravenous (IV) moderate sedation, a minimum of 60 hours, including patient management, is required.3

In recent years, outpatient surgery in the practice of medicine has greatly increased in popularity. Minor surgical procedures on the limbs, trunk, and face are easily completed with the administration of local anesthetics by general surgeons, dermatologists, cosmetic, and plastic and reconstructive surgeons.5–8 Until recently, however, little consideration was given to the degree of patient anxiety toward this type of surgical procedure. The patient faces these nondental surgical procedures with the same dread as may be seen in dental patients. The techniques and concepts discussed in this book are as appropriate for nondental surgery as they are in dentistry.

NO ANESTHESIA

The extreme left-hand portion of the spectrum of pain and anxiety control (see Figure 3-1) comprises a small group of patients who require absolutely no sedation or local anesthesia during their dental treatment. Although quite rare, it is probable that a dentist or hygienist will be called upon to treat one or more of these persons at some time. For whatever reason—anatomic, physiologic, psychological, cultural, or religious—these patients either do not feel pain or do not react to it, and they are able to tolerate any form of dental treatment without the need for any sort of drug intervention.

IATROSEDATION

Iatrosedation, defined as the relief of anxiety through the dentist’s behavior, is the building block for all other forms of psychosedation. The term and the technique of iatrosedation were created many years ago by Dr. Nathan Friedman, then chairman and founder of the Department of Human Behavior, University of Southern California School of Dentistry.9 Discussed in depth in Chapter 6, iatrosedation may briefly be described as a process involving several steps: recognition by the dentist of the patient’s anxieties toward dentistry, management of the information gathered by the dentist from the patient, and a commitment by the dentist to aid the patient during dental treatment.

Simply stated, iatrosedation is a technique of communication between the dentist and the patient that creates a bond of trust and confidence. Patients possessing trust and confidence in their health care provider (physician, dentist, or other health care professional) are well on their way to being more relaxed and cooperative, without the need for supplemental pharmacosedation.10

Another important benefit of the use of iatrosedation in the practice of medicine and dentistry is the prevention of possible medicolegal complications. Lack of effective communication between the health care professional and patient is a leading cause of suits brought against medical and dental professionals. In some estimates, up to 37% of all malpractice actions are a result of a lack of communication and trust between the doctor and patient.11

OTHER NONDRUG PSYCHOSEDATIVE TECHNIQUES

Hypnosis has been used for many years for the management of both pain and anxiety. When employed by a trained hypnotherapist, in the proper clinical environment, and on the appropriate patient, hypnosis has proved to be a highly effective means of achieving both a relaxed and a pain-free treatment environment.12

Nondrug techniques are mentioned here for the sake of completeness. Developments in this field are occurring so rapidly that it is virtually impossible to include all of them in our compendium of available techniques. Nondrug techniques for the management of either pain or anxiety, or both, include acupuncture,13 acupressure, audioanalgesia,14 biofeedback,15 electroanesthesia (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [TENS], electroanesthesia [EA], electronic dental anesthesia [EDA]),16 and electrosedation.

ROUTES OF DRUG ADMINISTRATION

To this point in discussing the management of treatment-related anxiety, we have not yet employed any technique that requires administration of a drug. Sedation produced without administration of drugs is termed iatrosedation. The use of drugs to control anxiety is termed pharmacosedation. Iatrosedation by itself will allow us to manage but a small percentage of our fearful patients. One advantage possessed by iatrosedative techniques is their ability to increase the effectiveness of any drugs that might be needed for the definitive management of the patient’s dental fears. Even though we may have to turn to pharmacosedation, the great majority of patients in whom iatrosedation has been used will require smaller doses of the drug(s) to bring about a comparable degree of moderate sedation.17

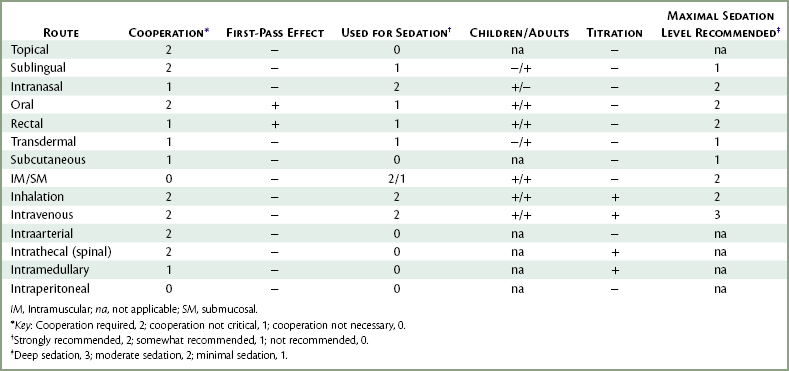

There are many routes through which drugs may be administered (Table 3-1). The first 13 of these routes are used within the practice of medicine, with the first 10 used in dentistry. The intraperitoneal route is used in veterinary medicine. These routes are as follows:

Oral

The oral route is the most common route of drug administration. It possesses advantages over parenteral routes of administration that make it useful in various situations involving the management of pain and anxiety. This route, however, has several significant disadvantages that must also be considered. Advantages include an almost universal acceptance by patients, ease of administration, and relative safety. Patients today are accustomed to taking drugs by mouth. It is quite rare to come upon an adult patient who objects to the oral route of administration. The younger child, however, often proves to be an unwilling recipient of orally administered drugs. Unwanted drug effects, such as overdosage, idiosyncrasy, allergy, and drug side effects, may occur whenever any drug is administered by any route, but such reactions are less likely to be noted when a drug is administered orally. When they do occur, they are normally less intense than those reactions that develop following parenteral administration. This is not meant to imply that life-threatening situations do not arise following oral drug administration. Indeed, cardiac arrest and anaphylaxis after oral drug administration have been reported.18,19

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses