Patient Management

LEARNING OUTCOMES

People are an essential part of the dental practice. The most important person in a dental practice is the patient. Never overlook the fact that each patient has a different background and different needs. Therefore, while communicating with patients, it is important to recognize each as an individual with specific needs and determine how to be sensitive to those needs. Remember that dentistry is a helping profession. Not only must every effort be made to alleviate patients’ discomfort, but patients must be taught to help themselves.

UNDERSTANDING PATIENT NEEDS

Each person who comes in contact with patients should have an understanding of the basic drives involved in motivating patients. Unless the dentist and staff have a basic understanding of these drives, they will become discouraged after numerous attempts fail to motivate patients to appreciate good dental health and quality dentistry.

With concern for humanism in this healthcare profession, it seems appropriate to be aware of the contributions of two humanistic psychologists, Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

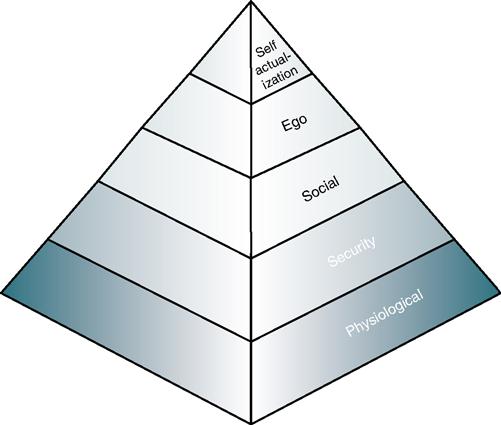

Dr. Abraham Maslow has described a hierarchy of needs (Figure 3-1) that aids in understanding how a person’s needs motivate his or her behavior. Maslow identified the following five basic levels of needs ranging from basic biological needs to complex social or psychological drives:

Relating this hierarchy to dentistry means getting to know the patients and the individuals with whom one is associated. Before a dentist can motivate a patient to accept a certain type of dental treatment, it must be understood where the patient is on the hierarchy of needs.

To help realize the application of these needs to dentistry, consider this situation. One of the practice’s patients is a bank president who is respected for his civic activities and has a warm, loving family and a fine home. The patient develops severe pain in the maxillary anterior area. The pain is sudden, sharp, and excruciating. It is difficult for him to eat, and there is a great deal of swelling in his upper lip. This person has dropped from perhaps a self-esteem level to the physiological, and the dentist must satisfy this physiological need immediately before attempting to suggest any further treatment.

Setting up payment plans for a patient often exposes a conflict of needs. A patient must ensure that basic needs of food, housing, and clothing are met, yet there may be a desire to meet social needs by improving appearance with some form of dental treatment. A conflict arises in the decision-making process when the patient is confronted with conflict on how to satisfy all of these needs with a specified income. The dentist and staff must make an effort to determine the patient’s needs, realize the patient’s potential conflict, and consider presenting an alternative treatment plan so the patient has some options.

This theory need not only apply to relationships with patients. It also can be applied to interactions among staff members. The dentist, assistant, and hygienist all have the same needs, and each is concerned, like the patient, about security today and in the future. Often conflict arises when a person becomes fixed at one level. There may appear to be no change in motivation, and the person remains unchanged in his or her perspective. This is evidenced often when a person has an interest in making money or increasing social status without regard for other people’s levels of motivation.

Perhaps one of the best lessons to be learned from Maslow’s theory is that an individual has a choice in determining his or her behavior. Although basic physiological and environmental needs have a strong influence, an individual makes choices voluntarily.

Rogers’ Client-Centered Therapy

Dr. Carl Rogers, another humanistic psychologist, believed that “it is the client who knows what hurts, what directions to go, what problems are crucial, what experiences have been deeply buried.” Rogers also suggests accepting the patient or other person as a genuine person with his or her own set of values and goals, and that these people must be treated with “unconditional positive regard.” Client-centered therapy assumes that patients know how they feel, what they want, and their priorities. Applied to dentistry, this philosophy encourages listening to the patient. Further, this concept suggests respecting patients as human beings, not just numbers, case studies, or research projects. These people have needs, and their desires should not be repressed. The combined concepts of Maslow and Rogers provide the groundwork for a humanistic, caring attitude, which should be a requisite for all healthcare providers.

BARRIERS TO PATIENT COMMUNICATION

Common Obstacles

Often practitioners are unable to communicate with patients because barriers have been established. One of the first barriers that may be created is prejudging a patient. A dentist may hesitate to present an extensive treatment to a patient because of the way the patient dresses or the type of car he or she drives. As a result, the patient is never told about alternative forms of treatment because his or her economic status has been prejudged. Often a person with a disability is prejudged. When a patient who has an artificial limb, is in a wheelchair, or has a visible birthmark on the face enters the dental office, frequently the first noticeable feature is the disability. If this patient is with a spouse or another person, the patient may go unnoticed while questions are directed to the accompanying person. As a dental healthcare worker, it is important to treat people with disabilities as any other patients and direct all communication to that person.

Another barrier occurs when one hears but does not listen. A dental professional should never be too busy to listen with understanding to a patient. Don’t just listen to the words. Listen to the meaning of the words and the feeling behind the meaning. Before presenting a personal point of view, be able to restate what has been said to the patient’s satisfaction. This may sound easy, but is not. Often people are too eager to present their own point of view and fail to understand the real meaning of what the patient is attempting to say. What is the patient really saying when he or she says, “I think I’ll wait to have that treatment done”? If the dental professional responds, “Oh, that’s okay, Mrs. Gates, I understand,” he or she won’t find out what the patient is really saying, and may cut off communication. The patient may really be saying, “I’m scared,” “I can’t afford it,” or “I don’t like the way you treat me.” The best way to arrive at the real meaning is to continue the dialogue until the patient’s true feelings are discerned. The following example demonstrates this idea:

Notice in this dialogue the assistant offered a solution to the problem so that it could be discussed further.

However, the dialogue may have continued along different lines, such as the following example:

In this case, the assistant rephrased what the patient said to arrive at the real meaning.

A third barrier is preoccupation. During daily routines many demands are placed on one’s time, and it is easy to begin to suddenly think about other activities while trying to communicate with a patient. Everyone has been in that position at one time or another. A patient is trying to explain why an appointment time is not convenient, and suddenly the dental professional realizes that she or he hasn’t heard a word that was said because of concentration on another problem. This often happens in an office that is understaffed. Each staff member has so much work to accomplish that listening to a patient sometimes just becomes an additional burden. Unfortunately patients are quick to recognize such preoccupation and may suddenly stop talking or eventually may even stop coming into the dental office. This type of situation re-emphasizes the service model illustrated in Chapter 1. As mentioned, the patient is the most important person in the office and should be given complete attention.

Unawareness of importance, impatience, and even hearing loss are barriers to communication. How important the problem is to a patient may not be realized, and the patient’s concern may simply be ignored as a whim. Likewise, one may inadvertently become impatient with a chatty young child or an older person who is slow. Furthermore, it is possible not to hear everything a person says because of an unrealized hearing loss.

It is not beneficial just to know about these barriers. The dental professional must be willing to evaluate him or herself. Before each contact with a patient, decide to ignore extraneous activities, and be willing to listen and understand a patient’s problem before offering a solution.

Recognizing Nonverbal Cues

Many books have been written in recent years defining and guiding the reader to recognize nonverbal communication cues. Nonverbal cues refer to the gestures and body movements a person makes in a given situation.

Every member of the dental staff should have some awareness of this area. Just as a “picture is worth a thousand words,” so a gesture can give meaning to a person’s inner feelings. Nonverbal communication provides feedback on the patient’s reactions.

The alert assistant is able to pick up these cues and interpret them while communicating with a patient. Care should be taken not to be misled by one gesture. A series of gestures generally give a more realistic indication of a person’s attitude. A dental office presents many opportunities to use and to receive nonverbal cues.

Nervousness

A patient who enters the reception room and sits down, locking the ankles together and clenching the hands, may be expressing fear by holding back emotions (Figure 3-2). This may occur in the dental chair when a person clenches the armrests and locks the ankles together (Figure 3-3). When the patient relaxes, he or she will automatically unlock the ankles.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Practice Note

Practice Note