Chapter 3

Paediatric dentistry

Contents

Principal sources and further reading R. Andlaw 1996 A Manual of Paedodontics, Churchill Livingstone. J. O. Andreasen 2007 Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth (4e), Blackwell Publishing. COPDEND/DOH 2007 Child Protection and the Dental Team  www.cpdt.org.uk. M. S. Duggal et al. 2002 Restorative Techniques in Paediatric Dentistry. Dunitz. R. R. Welbury 2005 Paediatric Dentistry (3e), OUP. BSPD policy documents and clinical guidelines

www.cpdt.org.uk. M. S. Duggal et al. 2002 Restorative Techniques in Paediatric Dentistry. Dunitz. R. R. Welbury 2005 Paediatric Dentistry (3e), OUP. BSPD policy documents and clinical guidelines  www.bspd.co.uk. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines

www.bspd.co.uk. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines  www.iadt-dentaltrauma.org.

www.iadt-dentaltrauma.org.

The child patient

Treat the patient not the tooth.

Treat the patient not the tooth.

Principal aims of Rx

Points to remember

The first visit

Treatment planning for children

Diagnosis

Dental caries is often a rapidly progressing condition in children. It is essential to secure an accurate ∆ before making a Rx plan. This is achieved by taking a history, doing an examination, and, where possible, taking bitewing radiographs.

Bitewings are important for an accurate ∆ unless approximal surfaces of the primary molars can be visualized (i.e. the dentition is spaced).

Bitewings are important for an accurate ∆ unless approximal surfaces of the primary molars can be visualized (i.e. the dentition is spaced).

Rx plan

The ultimate aim in dentistry for children is for the child to reach adulthood with good dental status and a positive attitude towards dental health and dental Rx. The final Rx plan will take into account the following considerations:

Remember to consider the developing occlusion:

Remember to consider the developing occlusion:

The Rx plan is drawn up visit by visit. Each visit has both a preventive and operative component (delivering one preventive message per visit).

As it is considered to be easier to administer LA for maxillary teeth, these teeth are usually treated before mandibular teeth.

Restorative care (i.e. repair) without prevention is of limited value. Dental caries is treated by ‘preventive’ measures; restoration purely repairs the damage caused by the carious process.

Children with caries in primary molars treated by prevention alone are likely to experience toothache/infection, especially if the child is young when the caries is first diagnosed. Therefore a combination of prevention and restoration/extraction is indicated for most children with caries in the 1° dentition.

Other considerations

Pain or evidence of infection may influence the order of the Rx plan.

Temporization (i.e. hand excavation and dressing) of open cavities at the start of Rx:

Delivery of care

Once the Rx plan has been decided upon:

Look out for any signs of underlying medical or social problems which may modify the Rx plan:

The anxious child

Techniques for behaviour management

Most of these are fancy terms to describe techniques that come with experience of treating children over a period of time.

General principles

Tell, show, do

Self-explanatory, but use language the child will understand.

Behaviour shaping

Aim to guide and modify the child’s responses, selectively reinforcing appropriate behaviour, whilst discouraging/ignoring inappropriate behaviour.

Reinforcement

This is the strengthening of patterns of behaviour, usually by rewarding good behaviour with approval and praise. If a child protests and is uncooperative during Rx, do not immediately abandon session and return them to the consolation of their parent, as this could inadvertently reinforce the undesirable behaviour. It is better to try and ensure that some phase of the Rx is completed, e.g. placing a dressing.

Modelling

Useful for children with little previous dental experience who are apprehensive. Encourage child to watch other children of similar age or siblings receiving dental Rx happily.

Desensitization

Used for child with pre-existing fears or phobias. Involves helping patient to relax in dental environment, then construct-ing a hierarchy of fearful stimuli for that patient. These are introduced to the child gradually, with progression on to the next stimulus only when the child is able to cope with previous situation.

Should parent accompany child into surgery?

Essential on first visit, thereafter depends upon child’s age. If in doubt ask child’s preference. However, if parent is dental phobic, their anxiety in the dental environment may be unhelpful, so in these cases it is probably wiser to leave mum or dad in the waiting room. Some children will play up to an over-protective parent in order to gain sympathy or rewards, and may prove more cooperative by themselves. However, many parents wish to be involved in, and informed about their child’s Rx. Ideally parents should be motivated positively and instructed implicitly to act in the role of the ‘silent helper’.

Sedation

Sometimes indicated for the genuinely anxious child who wishes to cooperate and also may help children with over-active gag reflexes and those where analgesia additional to LA may be needed (e.g. for difficult extractions such as 6s).

Oral:

Drugs such as midazolam and chloral hydrate can be used, although specialized knowledge and skills are required.

Intramuscular:

rarely used in children.

Intravenous:

rarely used in children.

Per rectum:

popular in some Scandinavian countries.

Inhalation:

uses nitrous oxide/oxygen mixture to produce RA and is most popular technique for use with children. Effective for ↓ anxiety and ↑ tolerance of invasive procedures in children who wish to cooperate but are too anxious to do so without help. It is a good idea not to carry out any Rx during the visit when the child is introduced to ‘happy air’. Let child position nose-piece themselves. Further details see Chapter 13.

Hypnosis

Hypnosis produces a state of altered consciousness and relaxation, though it cannot be used to make subjects do anything that they do not wish.1 Attendance at a course is necessary to gain experience with susceptible subjects. It can be described as either a way of helping the child to relax, or as a special kind of sleep.

General anaesthesia

Allows dental rehabilitation &/or dental extractions to be achieved at one visit. GA should only be used for dental Rx when absolutely necessary (i.e. when other methods of management, e.g. local analgesia or sedation, are deemed unsuitable). Alternative strategies and the risks of GA must be discussed to enable parents to make an informed decision. From December 2001 dental GA in the UK can only be provided in a hospital setting.2

The risk of unexpected death of a healthy person:

Other behaviour problems and their management

The child with toothache

When faced with a child with toothache the dentist has to use his clinical acumen to try and determine the pulpal state of the affected tooth/teeth, as this will decide the Rx required. To that end the following investigations may be employed:

History

Take a pain history (see p. 220) from the child and parent. Beware of variations in accuracy; anxious children may deny being in pain when faced with an eager dentist, whereas parents who feel guilty for delaying seeking dental Rx may exaggerate pain. Remember some pathology is painless, e.g. chronic periradicular periodontitis.

Examination

Swelling, temperature, lymphadenopathy. Intraorally look for caries, abscesses, chronic buccal sinuses, mobile teeth (? due to exfoliation or apical infection) and erupting teeth.

Percussion

Can be unreliable in children. Care needed to establish a consistent response.

Sensibility testing

Again, this is unreliable in primary teeth, but for permanent teeth a cotton-wool roll, ethyl chloride, and considerable ingenuity may provide some useful information. In older children electric pulp testing may be helpful.

Radiographs

Bitewing X-rays are most useful, because not only are they less uncomfortable for small mouths than periapicals, but they also show up the bifurcation area where most 1° molar abscesses start.

Remember, the only 100% accurate method is histological!

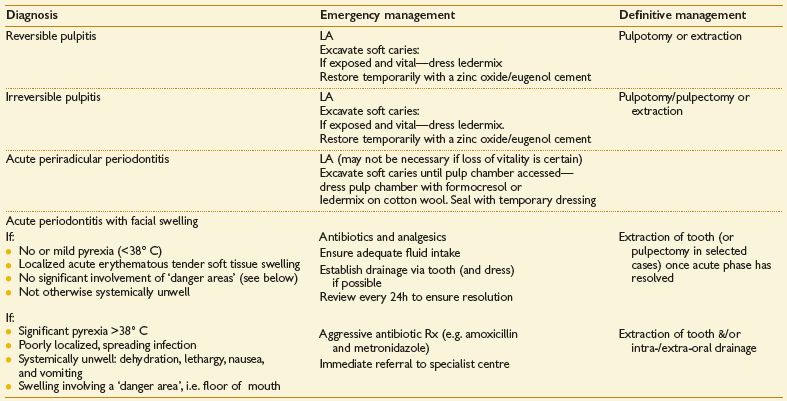

Diagnosis

Fleeting pain on hot/cold/sweet stimuli = reversible pulpitis.

Longer-lasting pain on hot/cold/sweet stimuli = irreversible pulpitis.

Spontaneous pain with no initiating factor (no mobility, not TTP) = irreversible pulpitis.

Pain on biting and pressure &/or swelling and tenderness of adjacent tissues, mobility = acute periradicular periodontitis.

With a fractious child keep examination and operative intervention to a minimum, doing only what is necessary to alleviate pain and win child’s trust.

If extractions under a GA are required consider carefully the long-term prognosis of remaining teeth to try and avoid a repeat of the anaesthetic in the near future.

Other common potential causes of toothache:

Abnormalities of tooth eruption and exfoliation

Natal teeth

are usually members of the 1° dentition, not supernumerary teeth, and so should be retained if possible. Most frequently occur in lower incisor region and because of limited root development at that age, are mobile. If in danger of being inhaled or causing problems with breast-feeding, they can be removed under LA.

Teething

As eruption of the 1° dentition coincides with a diminution in circulating maternal antibodies, teething is often blamed for systemic symptoms. However, local discomfort, and so disturbed sleep, may accompany the actual process of eruption. A number of proprietary ‘teething’ preparations are available, which usually contain a combination of an analgesic, an antiseptic, and anti-inflammatory agents for topical use. Having something hard to chew may help, e.g. teething ring.

Eruption cyst

is caused by an accumulation of fluid or blood in the follicular space overlying an erupting tooth. The presence of blood gives a bluish hue. Most rupture spontaneously, allowing eruption to proceed. Rarely, it may be necessary to marsupialize the cyst.

Failure of/delayed eruption

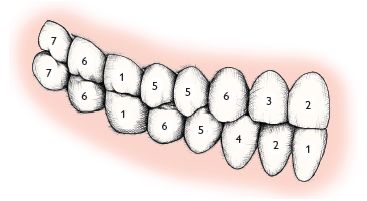

Disruption of normal eruption sequence (see Figure 3.1) and asymmetry in eruption times of contralateral teeth >6 months warrants further investigation.

Disruption of normal eruption sequence (see Figure 3.1) and asymmetry in eruption times of contralateral teeth >6 months warrants further investigation.

Fig. 3.1 Normal sequence of eruption (permanent dentition).

It must be remembered that there is a wide range of individual variation in eruption times. Developmental age is of more importance in assessing delayed eruption than chronological age.

General causes

Hereditary gingival fibromatosis, Down syndrome, Gardner syndrome, hypothyroidism, cleidocranial dysostosis, rickets.

Local causes

(p. 142).

(p. 142).Infraoccluded (ankylosed) primary molars

Occur where the 1° molar has failed to maintain its position relevant to the adjacent teeth in the developing dentition and is therefore below the occlusal level of adjacent teeth. Caused by preponderance of repair in normal resorptive/repair cycle of exfoliation. This is usually self-correcting (if the permanent successor is present and not ectopic) and the affected tooth is exfoliated at the normal time.1 However, where the premolar is missing or where the infraoccluded molar appears in danger of disappearing below the gingival level, extraction may be indicated.

Ectopic eruption of the upper first permanent molars

resulting in an imp-action of the tooth against the  occurs in 2–5% of children. It is an indication of crowding. In younger patients (<8yrs) it may prove self-correcting (‘jump’). If still present after 4–6 months (‘hold’) or in older children, insertion of an orthodontic separating spring (or a piece of brass wire tightened around the contact point) may allow the

occurs in 2–5% of children. It is an indication of crowding. In younger patients (<8yrs) it may prove self-correcting (‘jump’). If still present after 4–6 months (‘hold’) or in older children, insertion of an orthodontic separating spring (or a piece of brass wire tightened around the contact point) may allow the  to jump free. More severe impactions should be kept under observation. If the

to jump free. More severe impactions should be kept under observation. If the  becomes abscessed or the

becomes abscessed or the  is in danger of becoming carious then the 1° tooth should be extracted. The resulting space loss can be dealt with later as part of the overall orthodontic Rx plan.

is in danger of becoming carious then the 1° tooth should be extracted. The resulting space loss can be dealt with later as part of the overall orthodontic Rx plan.

Premature exfoliation

Most common reason for early tooth loss is extraction for caries. Traumatic avulsion is less common. More rarely, systemic disease such as leukaemia may result in an abnormal periodontal attachment and thus premature tooth loss. Alveolar bone loss in a young child is a serious finding and warrants referral.

Abnormalities of tooth number

Anodontia

Means complete absence of all teeth. Rare. Partial anodontia is a misnomer.

Hypodontia (Oligodontia)

Developmental absence of one or more teeth.

Prevalence 1° dentition: 0.1–0.9%, 2° dentition: 3.5–6.5%.1 In Caucasians most commonly affected teeth are 8 (25–35%),  (2%), lower 5 (3%). Affects F > M and is often associated with smaller than average tooth size in remainder of dentition. Peg-shaped

(2%), lower 5 (3%). Affects F > M and is often associated with smaller than average tooth size in remainder of dentition. Peg-shaped  often occurs in conjunction with absence of contralateral

often occurs in conjunction with absence of contralateral  NB

NB  migrates down guided by the distal aspect of

migrates down guided by the distal aspect of  . When

. When  is absent, peg-shaped, or small-rooted, it is important to monitor the maxillary canine for signs of ectopic eruption.

is absent, peg-shaped, or small-rooted, it is important to monitor the maxillary canine for signs of ectopic eruption.

Aetiology

Often familial—polygenic inheritance. Also associated with ectodermal dysplasia and Down syndrome.

Rx:

1° dentition—none. 2° dentition—depends on crowding and maloccusion.

—none.

—none.

— see p. 112.

— see p. 112.

–— (NB

–— (NB  sometimes develop late). If patient crowded, extraction of

sometimes develop late). If patient crowded, extraction of  , either at around 8yrs for spontaneous space closure or later if space is to be closed as a part of orthodontic Rx. If lower arch well-aligned or spaced, consider preservation of

, either at around 8yrs for spontaneous space closure or later if space is to be closed as a part of orthodontic Rx. If lower arch well-aligned or spaced, consider preservation of  , and bridgework later.

, and bridgework later.

Hyperdontia

Better known as supernumerary teeth. Prevalence 1° dentition 0.8%, 2° dentition 2%.1 Occurs most frequently in premaxillary region. Affects M>F. Associated with cleido-cranial dysostosis and CLP. In about 50% cases $ in 1° dentition followed by $ in 2° dentition, so warn mum!

Aetiology

Theories include: offshoot of dental lamina, third dentition.

Classification

either by

| Shape | or | Position |

| Conical (peg-shaped) | Mesiodens | |

| Tuberculate (barrel-shaped) | Distomolar | |

| Supplemental | Paramolar | |

| Odontome |

Effects on dentition and treatment

to fail to erupt. Rx: extract $ and ensure sufficient space for unerupted tooth to erupt. May require extraction of primary teeth &/or permanent teeth and appliances. Then wait. Average time to eruption in these cases is 18 months.1 If after 2yrs unerupted tooth fails to erupt despite sufficient space may require conservative exposure and orthodontic traction.

to fail to erupt. Rx: extract $ and ensure sufficient space for unerupted tooth to erupt. May require extraction of primary teeth &/or permanent teeth and appliances. Then wait. Average time to eruption in these cases is 18 months.1 If after 2yrs unerupted tooth fails to erupt despite sufficient space may require conservative exposure and orthodontic traction.Abnormalities of tooth structure

Disturbances in structure of enamel

Enamel usually develops in two phases, first an organic matrix and second mineralization. Disruption of enamel formation can therefore manifest as:

Hypoplasia

Caused by disturbance in matrix formation and is characterized by pitted grooved, or thinned enamel.

Hypomineralization

Hypocalcification is a disturbance of calcification. Affected enamel appears white and opaque, but post-eruptively may become discoloured. Affected enamel may be weak and prone to breakdown. Most disturbances of enamel formation will produce both hypoplasia and hypomineralization, but clinically one type usually predominates.

Aetiological factors

(not an exhaustive list)

Localized causes:

Infection, trauma, irradiation, idiopathic (see enamel opacities, p. 72).

Generalized causes:

Chronological hypoplasia

So called because the hypoplastic enamel occurs in a distribution related to the extent of tooth formation at the time of the insult. Characteristically, due to its later formation,  is affected nearer to the incisal edge than

is affected nearer to the incisal edge than  or

or  .

.

Fluorosis, p. 28

Treatment of hypomineralization/hypoplasia depends on extent and severity:

Posterior teeth

Small areas of hypoplasia can be fissure-sealed or restored conventionally, but more severely affected teeth will require crowning. SS crowns (p. 86) can be used in children as a semi-permanent measure.

Anterior teeth

Small areas of hypoplasia can be restored using composites, but larger areas may require veneers (p. 250) or crowns. For Rx of fluorosis, see p. 72.

Molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH)(Figure 3.2)

Fig. 3.2 Upper first permanent molar in a patient with molar incisor hypomineralization, prior to restoration.

Rx options include intracoronal restoration, SS crowns, or extraction (p. 137). Consider partial composite veneering for incisors.

Amelogenesis imperfecta

Many classifications exist, but generally these are classified by the type of enamel defect &/or the mode of inheritance.

Main types:

Hypoplastic

—Enamel may be thin (smooth or rough) or pitted. Most commonly autosomal dominant inheritance.

Hypocalcified

—Enamel is dull, lustreless, opaque white, honey, or brown coloured. Enamel may breakdown rapidly in severe cases. Sensitivity ↑, calculus ↑ common. May be autosomal dominant or recessive.

Hypomaturation

—mottled or frosty looking white, opacities, sometimes confined to incisal third of crown (‘snow-capped teeth’).

Usually both 1° and 2° dentitions and all the teeth are affected. The different subgroups give rise to a wide variation in clinical presentation, ranging from discoloration to soft &/or deficient enamel. It is therefore difficult to make general recommendations, but it is wise to seek specialist advice for all but the mildest forms. Rx: in more severe cases, SS crowns and composite resin can be used to maintain molars and 2° incisors, prior to more permanent restorations when child is older.

Disturbances in the structure of dentine

Disturbances in dentinogenesis include dentinal dysplasias (types I and II), regional odontodysplasia, vitamin D-resistant rickets, and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome—all of which are rare.

Dentinogenesis imperfecta

(hereditary opalescent dentine) is more common affecting 1 in 8000. Both 1° and 2° dentitions are involved, although later-formed teeth less so. Main types:

Affected teeth have an opalescent brown or blue hue, bulbous crowns, short roots, and narrow flame-shaped pulps. The ADJ is abnormal, which results in the enamel flaking off, leading to rapid wear of the soft dentine. Rx: along similar lines as for severe amelogenesis

Early recognition and Rx of amelogenesis and dentinogenesis imperfecta important to prevent rapid tooth wear.

Early recognition and Rx of amelogenesis and dentinogenesis imperfecta important to prevent rapid tooth wear.

Disturbances in the structure of cementum

Hypoplasia and aplasia of cementum are uncommon. The latter occurs in hypophosphatasia and results in premature exfoliation. Hypercementosis is relatively common and may occur in response to inflammation, mechanical stimulation, or Paget’s disease, or be idiopathic. Concrescence is the uniting of the roots of two teeth by cementum.

Abnormalities of tooth form1

Normal width  = 8.5mm,

= 8.5mm,  = 6.5mm.

= 6.5mm.

Double teeth

Gemination

occurs by partial splitting of a tooth germ.

Fusion

occurs as a result of the fusion of two tooth germs. As fusion can take place between either two teeth of the normal series or, less commonly, with a $ tooth, then counting the number of teeth will not always give the correct aetiology.

As the distinction is really only of academic interest, the term ‘double teeth’ is to be preferred. Both 1° and 2° teeth may be affected and a wide variation in presentation is seen. The prevalence in the 2° dentition is 0.1–0.2%.

Rx

for aesthetics should be delayed to allow pulpal recession. If the tooth has separate pulp chambers and root canals, separation can be considered. If due to fusion with a $ tooth, the $ portion can be extracted. Where a single pulp chamber exists either the tooth can be contoured to resemble two separate teeth or the bulk of the crown reduced.

Macrodontia/megadontia

Generalized macrodontia is rare, but is unilaterally associated with hemifacial hypertrophy. Isolated megadont teeth are seen in 1% of 2° dentitions.

Microdontia

Prevalence 1° dentition <0.5%. In 2° dentition overall prevalence is 2.5%. Of this figure 1–2% is accounted for by diminutive  . Peg-shaped

. Peg-shaped  often have short roots and are thought to be a possible factor in the palatal displacement of

often have short roots and are thought to be a possible factor in the palatal displacement of  (p. 142).

(p. 142).  also commonly affected.

also commonly affected.

Dens in dente

This is really a marked palatal invagination, which gives the appearance of a tooth within a tooth. Usually affects  , but can also affect premolars. Where the invagination is in close proximity to the pulp, early pulp death may ensue. Fissure sealing of the invagination as soon as possible after eruption may prevent this, but is often too late. Conventional RCT is difficult and extraction is usually required.

, but can also affect premolars. Where the invagination is in close proximity to the pulp, early pulp death may ensue. Fissure sealing of the invagination as soon as possible after eruption may prevent this, but is often too late. Conventional RCT is difficult and extraction is usually required.

Dilaceration

Describes a tooth with a distorted crown or root. Usually affects  . Two types seen, dependent upon aetiology.

. Two types seen, dependent upon aetiology.

| Developmental2 | Traumatic |

| Crown turned upward and labially | Crown turned palatally |

| Regular enamel and dentine | Disturbed enamel and dentine |

| Usually no other affected teeth | formation seen |

| Affects F > M |

The traumatically induced type is caused by intrusion of the 1° incisor, resulting in displacement of the developing 2° incisor tooth germ. The effects depend upon the developmental stage at the time of injury.

Rx: depends upon severity and patient cooperation. If mild it may be possible to expose crown and align orthodontically provided the apex will not be positioned against the labial plate of bone at the end of the Rx, otherwise extraction indicated.

Turner tooth

Term used to describe the effect of a disturbance of enamel and dentine formation by infection from an overlying 1° tooth therefore usually affects premolar teeth. Rx: as for hypoplasia, p. 66.

Taurodontism

Of academic interest only, but seems to crop up on X-rays in exams much more frequently than in clinical practice. Means bull-like, and radiographically an elongation of the pulp chamber is seen. Rx: none required.

Abnormalities of tooth colour

Extrinsic staining

By definition this is caused by extrinsic agents and can be removed by prophylaxis. Green, black, orange, or brown stains are seen, and may be formed by chromogenic bacteria or be dietary in origin. Chlorhexidine mouthwash causes a brown stain by combining with dietary tannin. Where the staining is associated with poor oral hygiene, demineralization and roughening of the underlying enamel may make removal difficult. Rx: a mixture of pumice powder and toothpaste or an abrasive prophylaxis paste together with a bristle brush should remove the stain. Give OHI to prevent recurrence.

Intrinsic staining

This can be caused by:

Enamel opacities

Are localized areas of hypomineralized (or hypoplastic) enamel. Fluoride (p. 28) is only one of a considerable number of possible aetiological agents.

Treatment

Four possible approaches:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

at age 9–10yrs (p.

at age 9–10yrs (p.  (p.

(p.  (p.

(p.