Human disease and patient care

3.1 Medical assessment

• is important to establish the suitability of the patient to undergo dental treatment and may significantly affect the dental management

• may prompt examination for particular oral manifestations

• may be particularly relevant when a sedation technique or general anaesthesia (GA) is being considered

Medical history

Questions should refer to known medical problems, past history and present general fitness. The answers can give an indication of severity and so provide an American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) grade (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1

The American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification of physical status

| Classification | Physical status |

| I | No organic or psychiatric disturbance |

| II | Mild-to-moderate systemic disturbance |

| III | Severe systemic disturbance |

| IV | Life-threatening severe systemic disturbance |

| V | Moribund patient unlikely to survive |

Physical examination

Observe the patient in general: Is the patient clinically well or are there any obvious generalised clinical signs, such as cyanosis, pallor or jaundice? Is the patient unusually anxious? Are they talking continuously? Do they appear calm but have sweaty palms? Weigh the patient and also take note of any excessive fat under the chin, particularly in a retrognathic mandible as this may indicate a less than ideal airway.

Check the cardiovascular system: The radial pulse should be checked for rate, rhythm, volume and character. The arterial blood pressure may be measured using a sphygmomanometer on the upper arm of the patient while they are sitting. This limited examination is the minimum that should be carried out for adult patients, for whom intravenous sedation is proposed.

Medical risk assessment

The dentist should routinely assess patients using a risk assessment system. The ASA classification of physical status offers a useful system (see Table 3.1) and can be incorporated into a medical history questionnaire (Table 3.2). The dentist should always take a verbal history alongside any questionnaire and should not delegate this responsibility to another member of the team.

Table 3.2

| ASA grade | |

| Do you have angina or do you experience chest pain on exertion? | II |

| Have you reduced your activities? | III |

| Has your chest pain got worse recently? | III |

| Do you get chest pain at rest? | IV |

| Have you had a heart attack? | II |

| Have you had a heart attack in the last 6 months? | IV |

| Do you have a heart murmer or valve dysfunction or an artificial heart valve? | II |

| Have you had heart surgery? | III |

| Have you had rheumatic fever? | III |

| Have you had endocarditis? | IV |

| Do you have heart palpitations without exertion? | II |

| If so, do you have to rest or lie down during palpitation? | III |

| Do you get short of breath or dizzy during palpitations? | IV |

| Have you ever had high blood pressure? | II |

| Do you have problems lying flat? | II |

| Do you need more than two pillows at night due to shortness of breath? | III |

| Do you tend to bleed more than normal after injury or surgery? | III |

| Do you bruise spontaneously? | IV |

| Do you have epilepsy? | II |

| If so, do you continue to have seizures? | III |

| Do you have asthma? | II |

| If so, do you use inhalers? | II |

| Is your breathing difficult today? | IV |

| Do you have hayfever or eczema? | II |

| Do you have other lung problems? | II |

| If so, are you short of breath after climbing stairs? | III |

| Are you short of breath getting dressed? | IV |

| Do you have diabetes? | II |

| Are you on insulin? | II |

| Is your diabetes poorly controlled at present? | III |

| Do you have thyroid disease? | II |

| If so, is your thyroid gland overactive? | II |

| Do you suffer from liver disease? | II |

| If so, have you had a liver transplant? | III |

| Do you have kidney disease? | II |

| Is so, are you having haemodialysis? | III |

| Have you had a kidney transplant? | III |

| Have you ever had malignant disease or leukaemia? | II |

| If so, have you ever had chemotherapy or bone marrow transplant? | III |

| Have you ever had radiotherapy? | IV |

| Do you have arthritis? | II |

| If so, rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis? | II |

| Do you have any neurological disorders? | II |

| Multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease or Huntington’s chorea? | II |

| Have you taken or are you taking any of the following medication? | |

| Anticoagulants? Corticosteroids? Bisphosphonates? Antidepressants, sleeping tablets or medication for anxiety? |

3.2 Dental relevance of the medical condition

The cardiovascular system

Congenital and rheumatic heart disease

Valvular anomalies and damage may predispose to colonisation and potentially fatal infective endocarditis following a bacteraemia caused by dental treatments, such as subgingival periodontal therapies or surgical procedures, including dental extraction. However, it is now known that the risk is actually very small and the routine use of prophylactic antibiotics is no longer indicated. Current guidelines should always be checked and institutional recommendations followed. It is sensible to restrict antibiotic prophylaxis for dental treatment to patients in whom the risk of developing endocarditis is the highest. The recommendations of one group (Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy) suggest high-risk patients are those that have had or have a history of endocarditis, cardiac valve replacement surgery or a surgically constructed systemic or pulmonary shunt or conduit.

Management: Good oral hygiene is probably the most important factor in reducing the risk of endocarditis in susceptible individuals and regular dental care and disease prevention are obviously paramount. Amoxycillin 3 g orally 1 hour before the dental procedure or clindamycin 600 mg orally if allergic to penicillin are appropriate antibiotics if indicated.

Hypertension

• Blood pressure should be controlled before sedation/GA for elective treatment and patients should continue to take their antihypertensive drugs up to and on the day of sedation/GA.

• Blood pressure should be monitored during treatment involving conscious sedation techniques.

• For treatment under local anaesthesia, solutions containing adrenaline (epinephrine) may be used safely providing that aspirating syringes are used to reduce the incidence of intravascular injection (which may cause hypertension, arrhythmia or trigger angina in susceptible patients).

Arrhythmias

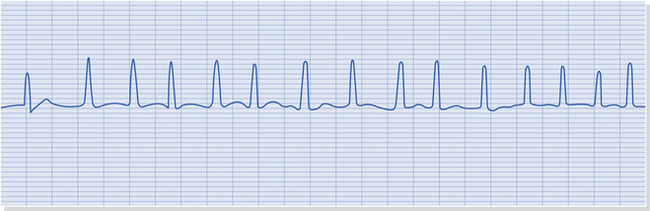

The patient may give a history of palpitations or have an irregular pulse, but an arrhythmias are only diagnosed accurately from an electrocardiogram. Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia and is present in 8% of those over 80 years (Fig. 3.1). This may be managed with beta-blockers (e.g. atenolol), calcium channel blockers (e.g. verapamil) or cardiac glycosides (e.g. digoxin) but patients may also be taking anticoagulation.

Angina and myocardial infarction

• Angina should be controlled before sedation/GA.

• Patients may be treated using conscious sedation techniques but require additional monitoring and should receive supplemental oxygen therapy.

• Preoperative glyceryl trinitrate should be considered for patients with angina receiving treatment under local anaesthetic (LA). LA solutions containing adrenaline (epinephrine) may be used safely. Aspirating syringes are recommended to reduce the incidence of intravascular injection, which may theoretically lead to an increase in hypertension.

The respiratory system

Chronic obstructive airways disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined as the presence of a productive cough for at least 3 months in 2 successive years. Fig. 3.2 shows a chest radiograph of a patient with COPD. A frequent cause is smoking. The severity may be assessed from the patient’s exercise tolerance, together with drug usage and the frequency of related hospital admissions.

• GA involves a risk of respiratory impairment.

• Intravenous conscious sedation techniques are also likely to further compromise respiratory function and should be undertaken in hospital.

• LA may be used safely. The patient may be more comfortable in a semi-supine or upright position, as they can become increasingly breathless in the supine position.

Asthma

• It is important to avoid GA drugs that release histamine such as atracurium and morphine.

• Conscious sedation techniques may be indicated in mild asthma to reduce anxiety and avoid an attack.

• Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be prescribed only if the patient has taken the drug before on more than one occasion without a hypersensitivity reaction.

Other respiratory diseases

Upper or lower respiratory tract infections: These do not contraindicate dental treatment under LA or conscious sedation, although the nasal obstruction of the common cold may make treatment with an open mouth uncomfortable for the patient. Similarly, patients may find it difficult to inhale nitrous oxide and oxygen. It is usually preferable to postpone treatment, especially if the patient is pyrexial. Elective GA treatment should be postponed because of the risk of causing much more serious infection as a consequence of a reduced immune response or intubation transferring micro-organisms further into the respiratory tract.

Haematological disorders

• Elective sedation/GA treatment should be postponed until the anaemia has been treated by the patient’s GP or specialist. Patients are at risk of hypoxia when respiratory depressant sedatives are administered and during induction and recovery of GA. Such a risk is more significant if the patient’s oxygen-carrying capacity is already reduced.

Sickle cell anaemia: Red cells sickle and cause infarcts or, rarely, haemolysis in sickle cell anaemia. Sickling tests detect the specific haemoglobin form (HbS). Electrophoresis distinguishes homozygous (SS), heterozygous (AS) states and other haemoglobin variants. Sickle cell crisis is precipitated by hypoxia, dehydration, pain and infection and therefore, prevention and prompt management of these is essential.

Leukaemia

• Elective dental treatment other than preventive should be postponed until a remission period.

• Infections should be treated aggressively with antibiotics and antifungal agents. NSAIDs should be avoided because of the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Local anaesthetic blocks should be avoided.

Bleeding disorders

Anticoagulant therapy

Anticoagulants are used in the treatment of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, following heart valve replacement and for those with atrial fibrillation who are at risk of embolisation. Treatment for deep vein thrombosis may last only 3–6 months but will continue for life for atrial fibrillation and those with mechanical prosthetic heart valves. A commonly used anticoagulant is warfarin, which antagonises vitamin K. Warfarin takes 36 hours or longer to peak anticoagulant effect which is measured by prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). The international normalised ratio (INR) comparing the patientʼs PT with that of a control is increased with warfarinisation. An INR near 1 is normal and patients taking anticoagulants are usually in the range 2–4.

• In the past, patients have had their warfarin dose adjusted to reduce the risk of bleeding during and after oral surgery, but more recently a small clinical trial suggested that this might not be necessary and the risk of thromboembolic event after withdrawal of warfarin outweighs the risk of bleeding after oral surgery. Patients within the normal range may not require any change to their warfarin dose at all for minor surgery but should be warned that there is an increased risk of bleeding after surgery. If possible, a single extraction should be undertaken in the first instance with further extractions at subsequent visits to limit the extent of surgery. An INR measurement should be carried out within 24 hours of surgery and preferably on the day of surgery.

• Patients should receive appropriate verbal and written information about postoperative care and how to access assistance should there be any postoperative bleeding, as should any other patient. Local measures for haemostasis are likely to be adequate.

• Patients who do bleed should be transferred to hospital for haematological management including the administration of vitamin K by slow intravenous injection or fresh frozen plasma.

• Patients undergoing more major surgery are likely to require reduction in their anticoagulation and this should be done in discussion with a haematologist who will advise. Similarly, haematological collaboration is required even for minor surgery for patients whose anticoagulation is not stable.

• Intramuscular injections should be avoided in all patients with a haemostasis disorder or on anticoagulants, and local anaesthetic regional nerve blocks should be avoided if possible and infiltration or intraligamentary injection techniques used instead. Metronidazole interacts with warfarin and should be avoided as should erythromycin which has unpredictable effect. Amoxycillin interferes less with warfarin but patients should be warned to look out for bleeding. Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) and, to a lesser extend other NSAIDS, should be avoided. The anticoagulant effect of warfarin is not usually affected by paracetamol.

Endocrine disease

• The patient should be reasonably well controlled before sedation/GA. When the patient is starved prior to a GA, they must have their oral hypoglycaemic drug or insulin adjusted. Non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus patients can usually withstand a short period of starvation but may need insulin if undergoing prolonged surgery. Their oral hypoglycaemic should be stopped the day before surgery.

• Patients with insulin-dependant diabetes mellitus should have their long-acting insulin omitted the night before surgery and blood glucose monitored. Insulin and glucose therapy is started using a variable-rate insulin infusion (soluble insulin 50 IU in 50 ml normal saline by syringe driver) and adjusted as required. The patient also should receive carbohydrate. Alternatively, the Alberti regime may be used if the patient is usually well controlled. This consists of an infusion of glucose 10%, 500 ml; human soluble insulin 10 IU; and potassium chloride (KCl) 10 ml, over 5 hours via a dedicated cannula. The insulin and KCl concentrations are adjusted according to the results, aiming for a blood glucose of 6–10 mmol/l.

• Hypoglycaemia must be avoided as it may cause brain damage. Blood glucose should be measured regularly with an automated blood glucose measurement device because control is upset by surgery and anaesthesia.

Hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism

There is a serious risk of arrhythmias if an untreated hyperthyroid patient receives a GA.

Hepatic disease

Clotting dysfunction: The diagnosis and severity should be confirmed by arranging for a coagulation screen prior to treatment and especially before surgery. Patients may need vitamin K or fresh frozen plasma to correct coagulation and, therefore, should be managed in hospital.

Drugs: Prescribing is a problem and many drugs should be used with caution or avoided completely in severe hepatic disease. Paracetamol, NSAIDs and sedatives are among these. Any drug prescribing should include reference to a drug formulary. It is difficult to predict the impairment of drug metabolism even when using liver function tests.

Renal disease

• Drug doses should be reduced as drug excretion may be reduced and NSAIDs should be avoided.

• Patients should receive dental treatment the day following dialysis when any heparin is no longer active but they are still at maximum benefit from the dialysis.

• Patients who have undergone renal transplantation will be receiving immunosuppressive drugs and will require an increase to their steroid dose prior to extensive treatment or GA. They may also require antibiotic prophylaxis.

Gastrointestinal disease

Peptic ulceration is a relatively common disease that can be exacerbated by NSAIDs. These drugs should not be prescribed for patients with such a history. Patients with Crohn’s disease may be taking corticosteroids or immunosuppressive treatment and so require early vigorous treatment of infections.

Radiotherapy

• Ideally patients should be made dentally fit before radiotherapy treatment in order to avoid the risk of extractions later. In the long term, periodontal diseases and caries can be controlled with adequate monitoring and with appropriate use of chlorhexidine oral rinse and fluoride applications.

• It is of great importance, therefore, that patients scheduled for radiotherapy undergo a thorough oral clinical and radiographic examination in order to minimise their dental needs post radiotherapy.

• The decision to remove any tooth must be based on its poor prognosis and inability to restore and maintain as, interestingly, even the removal of teeth in preparation for radiotherapy is known to increase the risk of osteoradionecrosis developing, hence the importance of minimally invasive dental treatment. If a tooth does require removal then preoperative chlorhexidine rinse, prophylactic antibiotics, atraumatic surgical technique and follow-up would be wise.

HIV/AIDs

• Obtain medical evaluation if symptomatic of HIV.

• For GA, risk assess for infections, bleeding and concurrent infections that could compromise respiratory function.

• Benzodiazepine activity for conscious sedation may be enhanced by protease inhibitors.

• Local anaesthetic blocks should be avoided if there is thrombocytopenia, as should NSAIDs.

• Infections should be treated aggressively with antibiotics and antifungal agents.

Neurological disorders

• Patients should be maintained on anticonvulsant therapy.

• Some GA drugs may enhance the toxic effects of anticonvulsants.

• Conscious sedation using a benzodiazepine may be indicated because of the anticonvulsant property.

• It may be advisable to undertake dental treatment under local anaesthesia using a mouth prop in patients with poorly controlled epilepsy.

Psychiatric disorders

There are many classification systems, some more helpful than others, but the distinction between the brain and the mind often provides a philosophical difficulty for patients and maybe also for some dentists. Patients may accept a psychiatric diagnosis that is recognised to be the result of organic brain disease but less readily accept one of non-organic cause. There remains prejudice about conditions that relate to the mind.

Organic pathology: Psychiatric disorders may lead to neglect of oral health. There may be potential for drug interaction between medications for illness and those used in dentistry, including conscious sedation and anaesthesia. Long-term oral pain may lead to depression.

Psychological orgin: Patients may present with dental, oral or facial physical symptoms that are of psychological cause. The dentist should exclude organic pathology, which may be responsible for the symptoms, by means of a careful history, thorough examination and appropriate special tests. The general dental practitioner may need to refer to a dental specialist to confirm the exclusion of organic pathology. The dentist or specialist who considers that the patient’s symptoms may be of psychological origin should communicate with the patient’s general medical practitioner, who may not otherwise be aware of multiple and variable symptoms and should arrange referral for psychiatric assessment.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses