Chapter 3

History and Systemic Risk Factors for Periodontal Diseases

Aims

The aims of this chapter are two-fold: first, to outline the key aspects of history taking in child, adolescent and young adult patients with periodontal problems; and secondly, to identify the principal systemic periodontal risk factors in these age groups that may be identified from the history.

Outcomes

After reading this chapter the practitioner should be aware of the aspects of history taking that are relevant for periodontal diseases in the younger age groups and consent issues that may arise when dealing with young patients. The dentist should also be able to elicit systemic risk factors for periodontal diseases and appreciate the relevance of such information for the diagnosis of periodontal conditions in children, adolescents and young adults.

Consent

Adults

Adults are presumed competent to give their consent for examination or treatment unless demonstrated otherwise. If there are any doubts about this, the question to ask is “Can this patient understand and weigh up the information needed to make this decision?”. This is an important issue because obtaining informed consent is based upon the patient making a decision to undertake treatment after having been provided with, and having understood, all benefits and risks of that treatment, and any alternatives.

Children

Before starting a consultation involving children, the clinician needs to be sure that the appropriate consent to examine or treat the child has been obtained. Most children will attend the dentist accompanied by an adult, but this may not always be the parent or guardian. It is important to determine the relationship between the child and accompanying adult so that an informed and reliable medical history can be taken and consent to treat can be given. At 16 years of age the patient is considered able to give their own consent although it may still be appropriate for parents or guardian to be involved and this may well be the adolescent’s preference. Even though in the UK a child’s consent can be valid if they are considered to be mature enough to understand the planned treatment, in most circumstances it is still prudent to include the parents or guardian in the discussion.

The History

The history enables the clinician to collect relevant personal details by interview, which will form the basis for the periodontal examination and in turn, the diagnosis of the periodontal condition. It is at this stage that the dentist will also begin to establish a professional relationship with the young adult, the teenager or the child and his or her parent, and will develop an impression of their health attitudes and any particular anxieties.

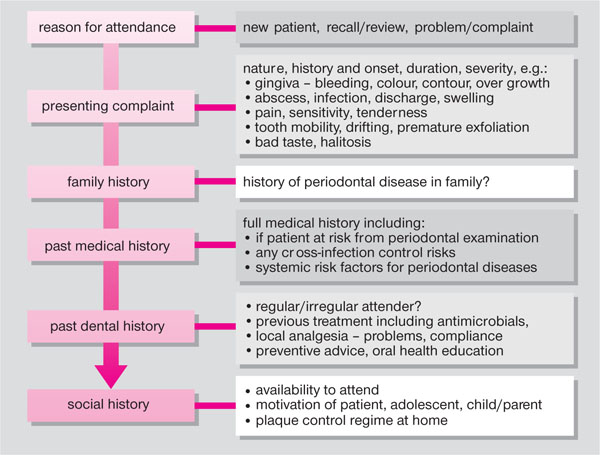

The history can be broadly divided into the following key areas (Fig 3-1), although the exact order of questioning is at the discretion of the individual dentist:

-

Presenting complaint and history of complaint/reason for attendance.

-

Family periodontal history.

-

Medical history.

-

Dental history.

-

Social history.

Fig 3-1 Key stages in the periodontal history taking of young patients.

Presenting Complaint and History of Complaint/Reason for Attendance

The reason for the patient’s visit and any particular complaint, together with the history of the complaint should be elicited. If the patient has presented in pain then details of the nature of the pain, location, onset and duration should be recorded. In many cases the patient will present for a check-up without pain. Patients do not always report signs or symptoms of dental disease unless prompted so specific questions should be asked of the patient and parent or guardian: for instance whether their gums bleed on brushing or if any teeth are sensitive.

Family History of Periodontal Diseases

Some periodontal diseases have a familial association and the dental history of other members of the family may then be relevant and provide an indication about the likely natural history of the disease process. It is worth asking: “Is there a history of gum disease, pyorrhoea or early tooth loss in the family – brothers, sisters, parents or grandparents?”.

Medical History

The medical history is important in identifying children, adolescents and young adults with medical problems who:

-

May be at risk when undergoing periodontal examination or treatment, due to:

-

a cardiac lesion

-

congenital heart disease

-

a confirmed significant heart murmur.

These medical conditions may put the patient at risk of infective endocarditis from a bacteraemia resulting from invasive periodontal procedures (such as periodontal probing, scaling and polishing, subgingival instrumentation, root planing or extractions), unless prophylactic antibiotics are given in accordance with current recommended guidelines.

-

-

May pose a cross-infection control risk to dental professionals and subsequent patients, e.g. carriers of hepatitis B – such patients should be managed according to current local infection control guidelines.

-

May have a systemic factor that can increase the risk of the young patient having or developing periodontal disease. The following list is based on the categories proposed by Chapple and Gilbert (2002) but is limited to those conditions pertinent to children, adolescents and young adults:

-

Genetic/inherited/inborn risk factors (see Chapters 2, 6 and 7 for more detailed accounts), including:

-

Down syndrome

-

Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome

-

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

-

hypophosphatasia

-

Cohen syndrome

-

Job syndrome

-

glycogen storage disease.

Conditions which all have a genetic component but come under other categories:

-

Infantile genetic agranulocytosis (haematological risk factor)

-

Chédiak-Higashi syndrome (haematological risk factor)

-

chronic granulomatous disease (haematological risk factor)

-

type 1 diabetes (metabolic risk factor).

-

-

Environmental risk factors, e.g. drug therapies (see Box 3-1).

-

Behavioural risk factors, e.g. smoking (Box 3-2), poor oral hygiene compliance.

-

Life style risk factors, e.g. stress. This may be caused by major life events or daily minor hassles (LeResche and Dworkin 2002). Periodontal disease may result because stress:

-

modulates neuroendocrine system

-

depresses immune system

-

increases the risk of inflammatory periodontal disease

-

produces indirect behavioural effects which can lead to decreased oral hygiene, increased smoking, and risk of pe/>

-

-

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses