Chapter 3

Dental Caries

Aim

To describe the radiological appearances of dental caries and demonstrate the scope and limitations of radiography in diagnosis.

Introduction

Identifying dental caries is probably the commonest diagnostic task performed by dentists. Radiology is important in caries diagnosis because of four factors:

-

it is non-invasive

-

we can view parts of teeth inaccessible to visual examination

-

the depth of a lesion can be assessed

-

successive images allow assessment of caries progression and risk.

Diagnosis of dental caries principally depends upon recognising clinical and radiological evidence of the disease process, although a number of other techniques can be used as aids. To understand the contribution of radiology to dental caries diagnosis, it is important to understand the pathological process and how this is represented on x-ray images.

As described in Chapter 1, x-ray absorption in a material depends upon:

-

atomic number

-

physical density

-

thickness.

The radiological visibility of dental caries depends upon its ability to alter one or more of these parameters. As far as radiology is concerned, dental caries leads to two important physical effects upon teeth: demineralisation and cavitation. Demineralisation causes the affected portion of the tooth to undergo a reduction in average atomic number and physical density by removal of calcium and phosphate-rich mineral. Cavitation removes a proportion of the thickness of enamel (and, later, dentine) from the tooth. Thus, the principal radiological sign of dental caries is radiolucency.

Radiographic technique

In caries diagnosis we are dealing with subtle changes in optical density with small dimensions and, as such, need images with high image resolution and optimal perspective. Thus, we are served best by using intraoral radiography, where the high resolution of non-screen film is combined with close approximation of the object with the film.

Optimal perspective for radiological caries diagnosis is provided by the bite-wing projection. The use of film holders with beam-aiming devices helps with standardisation between individuals and reproducibility within an individual.

Types of caries

Dental caries can affect any part of the tooth exposed to the oral environment. However, it typically occurs in characteristic sites:

-

proximal

-

occlusal

-

buccal/lingual

-

root surface (cemental)

-

secondary (recurrent) around restorations.

Proximal caries

The susceptible area of the proximal surface of the tooth is that between the contact point and the crest of the gingivae. The radiological appearance of proximal caries depends upon the stage of the disease process.

“Pre-radiological”

From histological studies we know that the earliest stage of proximal caries is an ovoid shaped demineralisation of enamel within the susceptible area. However excellent the radiograph, there is an initial stage where there will be no perceptible radiolucency. A figure of approximately 40% demineralisation of affected enamel is widely quoted as being required before there will be a radiolucency. This threshold of visibility is, however, only a rough guide and will vary from tooth to tooth and from radiograph to radiograph.

Enamel Lesion

The radiological appearance reflects the shape of the histological proximal caries lesion. The shape is triangular with its base at the enamel surface (Fig 3-1). The radiological picture will underestimate lesion depth. Indeed, as the lesion deepens, it will be superimposed upon proportionately more sound enamel, further contributing to underestimation of lesion depth.

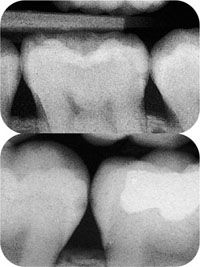

Fig 3-1 Enamel caries lesions. The bottom film shows small lesions of different sizes on 47 mesially and 46 distally, while the top film shows a lesion distally on 36 that is at the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) and possibly just into dentine.

The Lesion at the Amelodentinal Junction

For dentists, the depth of the caries lesion in relation to the amelodentinal junction (ADJ) is important in relation to treatment decisions. Many clinicians will choose to restore the tooth where the caries lesion has radiologically extended to the ADJ. While this is a pragmatic approach it is also imperfect. Cavitation is the appropriate threshold for intervention, but the relationship between cavitation and the radiological appearance is not predictable. Around one-half of molar/premolar proximal lesions with radiolucencies in the inner half of enamel or deeper will be cavitated, while the figure for cavitation rises to around 70% of lesions that radiologically extend to the outer half of dentine or deeper. The risk of cavitation is, however, higher for lesions extending into dentine in high caries risk individuals than in low risk patients.

Dentine Lesion

Once the caries has penetrated the full thickness of enamel, it spreads laterally as well as deeper into dentine. This lateral extension usually exceeds the maximum lateral dimension of the overlying enamel lesion. The dentine lesion appears as a triangular or semicircular radiolucency with its base on the ADJ (Figs 3-2 and 3-3). As with enamel lesions, the true depth is greater than the radiological lesion size would suggest.

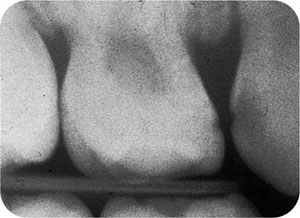

Fig 3-2 Dentinal lesion distally in 53, with the typical large dentine radiolucency compared with the small enamel radiolucency. Note also the enamel lesion mesially in 54.

Fig 3-3 Dentinal lesion mesially on 36.

Lesions at the Pulp

Left untreated, proximal caries may progress to involve the pulp. Ostensibly, while the juxtaposition of lesion and pulp on a radiograph might seem easy to diagnose as pulp involvement, the three-dimensional relationship of pulp and lesion may mean that there is superimposition of one upon the other without true contact.

Factors Affecting Radiological Interpretation of Proximal Caries

The factors governing the visibility of proximal caries include:

-

shape of lesion

-

shape of tooth

-

x-ray beam/tooth geometry

-

radiographic density and contrast

-

viewing conditions

-

observer variability.

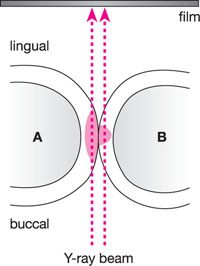

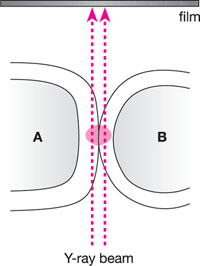

The first two of these affect radiological visibility in an inter-related way. An enamel lesion with a short buccolingual dimension will have proportionally more overlying sound enamel than a lesion with a long buccolingual dimension (Fig 3-4). Two lesions of exactly the same shape and size will appear radiologically different where the affected teeth have a different cross-sectional shape. For example, a lower premolar has a very rounded proximal surface and a lower molar a more “square” surface. This means that a lesion may produce a visible radiolucency in the premolar while not doing so if it were in the molar (Fig 3-5).

Fig 3-4 Diagram illustrating the effect of caries buccolingual dimension on radiological visibility. The lesion in tooth A is long buccolingually, with less superimposed sound enamel than that in tooth B. Despite the lesions having the same depth into enamel, that in tooth A would be more obvious on a radiograph.

Fig 3-5 Diagram illustrating the effect of tooth cross-sectional shape on caries radiological visibility. The lesions in both teeth are of identical/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses