3 Clinical Digital Photography

There is no more important instrument in cosmetic surgery than the camera.

Equipment

I am not a proponent of the dedicated photography suite, mainly because I am constantly taking clinical images; having to stop and move a patient to a single room in my office would create an unworkable bottleneck in my busy practice. Instead, I have the ability to make high-quality, standardized images in every room in my office. On the back of the door in any room where patients are evaluated, I have installed a photographic cloth background (I prefer sky blue) on a movable frame (Figures 3-1 to 3-3). Since some patients are tall and some are short, the frame is on a moveable track that can be adjusted up or down to accommodate individual height. Because I only perform head and neck cosmetic facial surgery, this works perfectly. For cosmetic surgeons who perform full-body surgery, a longer frame can be used.

FIGURE 3-2 A sky blue nonreflective photographic cloth is attached to the frame and serves as the background.

FIGURE 3-3 Using a simple off-the-shelf digital camera, high-quality shadowless images are easily made.

Cameras

Although there are numerous 35-mm single-lens reflex digital cameras with detachable lenses available, I have grown to prefer the smaller vacation-type cameras for their compactness and portability (Figure 3-4). These cameras can be carried from room to room in my scrub pants pocket and thrown in my briefcase without taking up room. These small-format cameras also have unbelievable video capability. I have a $1500 high-definition digital video camcorder, but I find myself taking many of my surgical videos with my cigarette pack–sized camera.

FIGURE 3-4 These common high-end, off-the-shelf general-use cameras work very well for clinical photography.

For those surgeons who want a more dedicated clinical camera, Lester A. Dine, Inc. (www.dinecorp.com) has for several generations made out-of-the-box, high-quality, user-friendly cameras. These cameras have been modified specifically for clinical photography.

Digital Editing Software

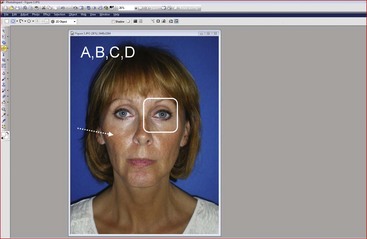

The other integral piece of digital photography is imaging software. Although Adobe PhotoShop (www.Adobe.com) is the most popular software, I have been using PhotoImpact (www.corel.com) for the past 15 years and find it a bit more user friendly but just as powerful. Imaging software is integral to producing quality images through enhancement, cropping, adding text and symbols, and stitching before-and-after pictures (Figure 3-5).

Taking and Making Pictures

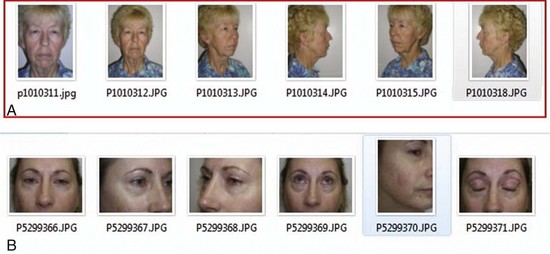

Depending upon the procedure to be performed, I generally take a full face-and-neck photo straight on, right and left three-quarter views, and right and left lateral views (Figure 3-6, A). For blepharoplasty or brow lift, I also take a close-up series of those views and a picture with the head straight but the eyes in an upward gaze (see Figure 3-6, B). Obviously, some instances call for pictures in repose and animation and are procedure specific. For instance, the surgeon may want animated images to show the condition of the facial nerve or pre-facelift images or the muscle movement in a pre-Botox image.

Standardization is everything in photography. To better standardize the three-quarter views, the patient should be rotated so the lateral canthus is in line with the soft-tissue nasion (or nasal radix) (Figure 3-7). By doing this on the right and left side, every patient will be at the same relative standardized angle.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses