Assessment in the Community

Jane E.M. Steffensen, RDH, BS, MPH, CHES

Upon completion of this chapter, the student will be able to:

• Explain the importance of assessment as a core public health function.

• Describe the roles of public health professionals in assessment.

• Discuss the basic terms and concepts of epidemiology.

• Describe the conceptual models that illustrate the determinants of health.

• Identify the determinants of health that affect the health of individuals and communities.

• Identify the specific stages of a planning cycle.

• Discuss a community oral health improvement process.

• Describe the main steps followed and key activities undertaken in a community oral health assessment.

• Compare and contrast the different methods of data collection that can be used in community health assessments.

Opening Statements

National Leading Health Indicators

| Indicators | Related Statistic* |

| • Access to health insurance | • 17% of children and adults (younger than 65 years) do not have health insurance (2008) |

| • Access to personal health care | • 4% of children and adults do not have a source of ongoing primary health care (2008) |

| • Prenatal care | • 16% of pregnant women have not received prenatal care during the first trimester (2002) |

| • Child immunizations | • 81% of young children (aged 19 to 35 months) are fully immunized (2006) |

| • Physical activity | • 67% of adults are not physically active on a regular basis (2008) |

| • Overweight and obesity | • 33% of adults are obese (2006) |

| • Tobacco use | • 21% of adults smoke cigarettes (2008) |

| • Substance abuse | • 20% of adolescents have used alcohol or illicit drugs during the past month (2007) |

| • Environmental quality | • 39% of Americans are exposed to harmful air pollutants (2004) |

| • Adult immunizations | • 67% of high risk older adults (65 years and older) not living in institutions are fully immunized for influenza and pneumonia (2008) |

*Statistics from Healthy People 2010 Database. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov/data2010/. Accessed February 2010.

Public Health Practice

Professional work in community health is dynamic because the environment changes continuously. Community health is affected by social, demographic, political, economic, and technologic changes. In this milieu, public health practitioners perform a broad array of duties focused on entire populations, with the overarching goal that people are healthy and live in healthy communities.1,2 The mission of public health is to “fulfill society’s interest in assuring the conditions in which people can be healthy.”3,4 Public health carries out this mission through organized, interdisciplinary efforts that address health problems in communities. Its mission is achieved through the application of health promotion and disease prevention and control efforts designed to improve health and enhance quality of life.1–4

Public health services incorporate the roles of a myriad of public health professionals in various sectors and from diverse disciplines that form the public health workforce in the United States.4,5 Public health professionals can belong to many professional disciplines, including oral health, nursing, nutrition, social work, health promotion, laboratory science, environmental health, administration, and epidemiology. Public health professionals have expertise in diverse public health practices.5 Several organizations and agencies have called for an increase in the visibility of public health and the core workforce that forms its foundation.1,2

As a result, collaborative efforts have been undertaken to enhance the recognition of the public health professions by measuring and improving the competency and consistency of public health workers nationwide. In 2005, the National Board of Public Health Examiners (NBPHE) was established to ensure that graduates from schools and programs of public health accredited by the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) have mastered the knowledge and skills relevant to contemporary public health.1 The NBPHE has developed and now administers an examination for the credential, Certified in Public Health (CPH).1 The national examination covers the five core areas of knowledge offered in CEPH–accredited schools and programs, as well as interdisciplinary cross-cutting areas relevant to contemporary public health. The core areas include biostatistics, environmental health sciences, epidemiology, health policy and management, and social and behavioral sciences.1,2 The cross-cutting areas are communication and informatics, diversity and culture, leadership, public health biology, professionalism, programs planning, and systems thinking.1,24646

In addition, the Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice has developed a set of core competencies for public health professionals to help strengthen public health workforce development.1,2 The competencies guide academic institutions and training providers to develop curricula and course content and to evaluate public health education and training programs. The competencies are used in practice settings as a framework for hiring and evaluating staff and assessing organization-wide gaps in skills and knowledge. The competencies are divided into the eight domains outlined in Box 3-1. Skills and knowledge are outlined within each domain, linked with important attitudes relevant to the practice of public health. This effort of the Council focuses on core competencies as they apply to three different categories of professional positions: front line staff, senior level staff, and supervisory and management staff.

Successful provision of public health services requires collaboration among public, nonprofit, and private partners within a given community and across various levels of government.4 To fulfill these goals, partnerships must have broad-based representation of constituency and stakeholder groups, including private, voluntary, nonprofit, and public agencies or organizations involved in health, mental health, substance abuse, environmental health protection, and public health.6 Examples of organizations and agencies that can be engaged in coalitions and collaborative partnerships to improve health in communities are presented in Appendix C.

Assessment: A Core Public Health Function

The contemporary principles of public health practice and science have been highlighted in several national reports.3–5 These consensus reports, published by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), detail past contributions and identify challenges to public health. They outline recommendations to improve the nation’s public health system and to ensure universal access to necessary public health services.

The Future of Public Health report specified three core public health functions that shape the basic practice of public health at the federal, state, and local levels.3 Health agencies and health departments must perform these functions to protect and promote health, wellness, and quality of life and to prevent disease, injury, disability, and death. These functions (as noted in Chapter 1) are (1) assessment, (2) policy development, and (3) assurance.3 This chapter emphasizes the core public health function of assessment in the community.

The IOM report called for public health agencies to promote, to facilitate, and—when necessary and appropriate—to perform community health assessments and to monitor change in key measures to evaluate performance. Assessment is defined as the regular and systematic collection, assemblage, analysis, and communication on the health of the community.3 The IOM report stated that assessment includes statistics on health status, community health needs, and epidemiologic and other studies of health problems.3

Roles of Public Health Professionals in Assessment

The effective use of information in the twenty-first century is crucial to ensure that healthy children and adults are living in healthy communities. Technologies available to public health professionals influence the capacity and ability to generate and collect a vast amount of information.1,2 In addition, evidence-based decision making is shaping the development of public health policies, programs, and practices.4 Therefore it is essential for public health practitioners to have skills in collecting, analyzing, disseminating, and effectively using data and information.5 Public health professionals must have the knowledge, skills, and values to do the following5,7:

• Work with communities to form partnerships

• Identify health issues and resources

• Determine priority health concerns

• Implement solutions to address community health problems

• Use data and evaluate outcomes of public health policies and interventions8

Public health dental hygienists are expected to play a leadership role in community oral health assessments.9,10 As agencies and organizations take on greater responsibility in conducting periodic assessments, public health dental hygienists will be involved in evaluating assets, needs, problems, and resources of the populations they serve in the community. Dental public health professionals working at the national, state, and local levels will be responsible for community oral health assessment.9 Essential public health services for oral health were developed to describe community oral health assessment (see Chapter 6 and Guiding Principles box).

Dental hygienists working within the public, private, or nonprofit sectors must have skills to assess community oral health problems, as well as evaluate outcomes of oral health population-based and personal oral health services. Dental hygienists working in community settings generally participate in a variety of assessment and evaluation activities. Examples of some of these roles and potential activities are shown in Box 3-2.

Overview of Epidemiology: Population-Based Study of Health

Public health dental hygienists involved in assessment and evaluation should become well versed in the basic concepts of epidemiology, which is a core science of community health. This section provides a broad overview of epidemiology. Table 3-1 provides the definitions of terms used in epidemiology and community health assessments.

Table 3-1

Common Terms Used in Epidemiology

| Term | Definition |

| Acute | Referring to a health effect, brief exposure of high intensity |

| Case | Epidemiologic study that compares persons with a disease or condition (“cases”) with another group of people from the same population without the disease or condition (“controls”). The study is used to identify risks and trends, suggest some possible causes for disease, or for particular outcomes. |

| Chronic | Referring to a health-related state lasting a long time. |

| Cohort study | The method of epidemiologic study in which subsets of a defined population can be identified and observed for a sufficient number of person-years to generate reliable incidence or mortality rates in the population subsets; usually a large population, study for a prolonged period (years), or both. (Synonym: concurrent, follow-up, incidence, longitudinal, prospective study.) |

| Cross-sectional study | A study that examines the relationship between diseases (or other health-related characteristics) and other variables of interest as they exist in a defined population at one particular time. |

| Dichotomous scale | A measurement scale that arranges items into either of two mutually exclusive categories. |

| Ecoepidemiology | Conceptual approach that unifies molecular, social, and population-based epidemiology in a multilevel application of methods aimed at identifying causes, categorizing risks, and controlling public health problems. |

| Ecologic study | Epidemiologic study in which the units of analysis are populations or groups of people rather than individuals. |

| Endemic disease | The constant presence of a disease or infectious agent within a given geographic area or population group. |

| Epidemic | Occurrence in a community or region of cases of an illness, specific health-related behavior, or other health-related events clearly in excess of normal expectancy. (From Greek epi [upon], demos [people].) |

| Eradication (of disease) | Termination of all transmission of infection by extermination of the infectious agent through surveillance and containment. |

| Etiology | Science of causes, causality; in common use, cause |

| Incidence | Number of instances of illness commencing, or of persons falling ill, during a given period in a specified population; more generally, the number of new events (e.g., new cases of a disease in a defined population) within a specified period of time. (Synonym: incident number.) |

| Index | In epidemiology and related sciences, usually refers to a rating scale or a set of numbers derived from a series of observations of specified variables (e.g., health status index, scoring systems for severity or stage of cancer, heart murmurs, mental retardation). |

| Monitoring | Intermittent performance and analysis of routine measurements aimed at detecting changes in the environment or health status of populations; not to be confused with surveillance, which is a continuous process. |

| Morbidity | Any departure, subjective or objective, from a state of physiologic or psychologic well-being; in this sense, sickness, illness, and morbid condition are similarly defined and synonymous. |

| Mortality | Related to death. |

| Multifactorial etiology | Referring to the concept that a given disease or other outcome may have more than one cause; a combination of causes or alternative combinations of causes may be required to produce the effect. |

| Occurrence | In epidemiology, a general term describing the frequency of a disease or other attribute or event in a population without distinguishing between incidence and prevalence. |

| Pandemic | An epidemic occurring over a very wide area and usually affecting a large proportion of the population. |

| Prevalence | Number of instances of a given disease or other condition in a given population at a designated time; when used without qualification, term usually refers to the situation at a specified point in time (point prevalence). |

| Prospective | A research design used that looks forward. |

| Retrospective | A research design that uses a review of past events. |

| Sensitivity | Proportion of truly diseased persons as identified by the screening test; the measure of the probability of a correct diagnosis or the probability that any given case will be identified by the test. (Synonym: true-positive rate). |

| Specificity | Proportion of truly nondiseased persons identified by the screening test; a measure of the probability of correctly identifying a nondiseased person with a screening test. (Synonym: true-negative rate.) |

| Surveillance | Ongoing systematic collection, analysis, interpretation of health data essential to planning, implementation, and evaluation of public health practice. Generally using methods distinguished by their practicability, uniformity, and rapidity. Closely integrated with the timely dissemination of health information to responsible parties. Application of data in public health decision making and use of data to prevent and control diseases and conditions. Surveillance is the essential feature of epidemiology. |

| Surveillance system | Functional capacity for data collection, analysis, and dissemination linked to public health programs. |

| Trend | A long-term movement in an ordered series (e.g., a time series); an essential feature is that the movement, while possibly irregular in the short term, shows movement consistently in the same direction over a long term. |

Adapted from Porta M, editor. A Dictionary of Epidemiology. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states and events in specified populations and the application of this study to the prevention and control of health problems.11 Epidemiologists consider the interactions and relationships among the multiple factors that influence health status and health problems.12 Methods used in epidemiology and research are combined to focus on comparisons between groups or defined populations. Epidemiologists make comparisons by examining the occurrences of the health events, locations, times, and variations to assess the distribution and determinants of health events.13 The principal factors analyzed in epidemiology are as follows:

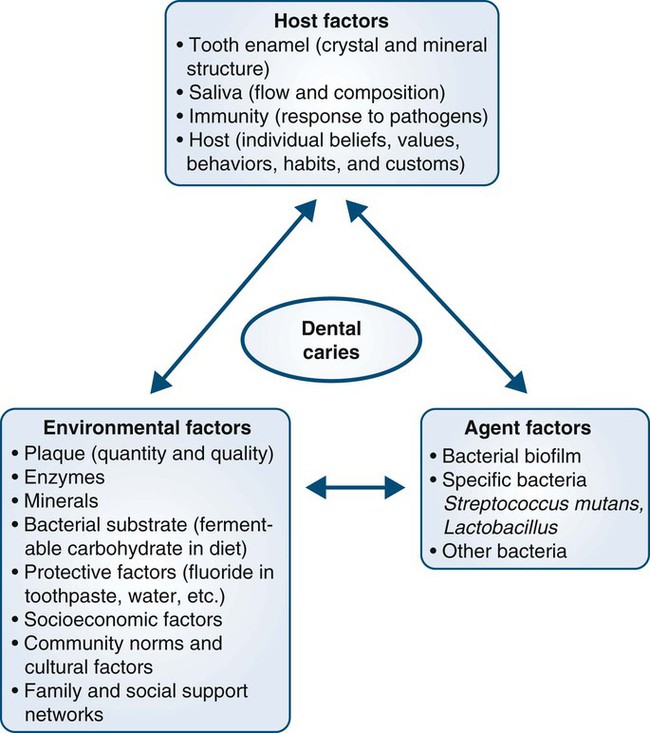

Epidemiology is based on a multifactorial perspective, with consideration given to the interacting relationships among host factors, agent factors, and environmental factors.12,14

Environmental Factors

The “epidemiologic triangle” depicts disease as the outcome of the interactions among host, agent, and environmental factors.12 For example, the development and progression of dental caries is attributed to multiple factors.15,16 Figure 3-1 portrays the epidemiologic triangle, with dental caries shown as a multifactorial disease influenced by host, agent, and environmental factors.

Uses of Epidemiology

Health represents a general balance among host, agent, and environmental factors; health problems occur when the balance is threatened by changes in host, agent, or environment.14 Prevention is concerned with maintaining or initiating a balance of these factors. Disease or health status depends on multiple factors such as exposure to a specific agent, strength of the agent, susceptibility of the host, and environmental conditions.12

Epidemiology can be used to provide different types of data and information.17 Epidemiologists in public health agencies are responsible for surveillance, investigation, analysis, and evaluation.12,14 The various uses of epidemiology are illustrated in Box 3-3. The three classifications of epidemiologic studies are outlined in the Guiding Principles box.

Changing Perspectives of Health

During the twentieth century, major transformations took place in the concepts of health and the understanding of the determinants of diseases, disabilities, and injuries. Many historic developments contributed to these expanded visions and had a profound effect on the health of individuals and populations.1,2,18 These developments contributed to changes in clinical health care and public health practice. Box 3-4 outlines broad trends that influenced the conceptions of health in the twentieth century.

Reports from studies have identified many factors that influence the health of individuals and populations.4,19–23,25–31 Several of these factors are generally recognized as broader determinants of health (e.g., employment; education; environment; income; shelter; food; social justice and equity; family, friends, and social supports; peace and safety; culture and race relations).14,22–24,31–33 Other factors (e.g., language, learning, meaningful work, recreation, self-esteem, personal control) are considered contributors to well-being. These factors may also be classified as follows14:

1. Inherited determinants are factors that are inborn or genetically determined.

2. Acquired determinants, which influence health and are obtained after birth and throughout life, include multiple factors such as infections, trauma, cultural characteristics, and spiritual values.

There has been a broadening of the concepts of health promotion and disease prevention from an individual focus toward a human ecologic perspective.17 Health became much more than just the absence of disability and disease. In 1948, The World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution defined health as “a state of complete physical, social and mental well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” The fundamental conditions and resources for health were described in 1986 by the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (Box 3-5). Improvement in health requires a secure foundation in these basic prerequisites.

Conceptual Models of the Determinants of Health

Many models describing the multiple factors that influence the broader dimensions of health in individuals and populations were developed in the second half of the twentieth century.4 Multicausal perspectives of health and disease began to take precedence over monocausal models.12 The epidemiologic triangle model waned as the emphasis on infectious diseases diminished in the later part of the centu/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses