(b)

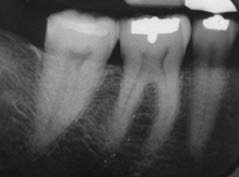

All the maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth responded normally to electric pulp and cold thermal testing. Periapical radiographs of the maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth revealed that the existing restorations were not close to the pulp chamber, while the periodontal ligament and lamina dura appeared to be of normal width and thickness, respectively (Figure 3.4.2a,b).

Figure 3.4.2 (a) and (b) Periapical radiographs of the maxillary and mandibular posterior quadrants.

(a)  (b)

(b)

A ‘bite test’ was performed; the aim of this investigation was to apply pressure to each cusp of the tooth under investigation. The patient was instructed to bite firmly on a commercially available ‘tooth sleuth’ as it was placed over each cusp (Figure 3.4.3). The bite test was repeated on each cusp of each tooth on posterior maxillary and mandibular teeth until the patient’s symptoms were reproduced. Once the patient’s symptoms were reproduced, a note was made of the specific tooth and cusp. The patient’s symptoms were reproduced when the tooth sleuth was applied to the disto-lingual cusp of tooth 46.

Figure 3.4.3 (a) Tooth sleuth should be placed (b) over the cusp tip of the tooth under investigation and the patient is then asked to bite firmly. This is repeated over each cusp tip of each tooth until the symptoms are reproduced.

(a)  (b)

(b)

Transillumination of each cusp with a fibre-optic light may also be used to confirm the presence and extent of a fracture.

Diagnosis and treatment planning

The diagnosis was cracked tooth syndrome associated with tooth 46. The symptoms were classical of an incomplete fracture of a vital posterior tooth.

What were the symptoms due to?

The symptoms were due to fluid movement within the dentinal tubules stimulating the sensory nerve fibres within the dentinal tubules and odontoblast layer. The patient found it difficult to localise the pain to a specific tooth as the periodontal ligament around the tooth was not inflamed, and therefore the tooth was not tender to percussion.

If the tooth was left untreated, irreversible pulpitis and necrosis may ensue, eventually resulting in periapical periodontitis. Unrestored or minimally restored teeth are commonly associated with the symptoms of crack tooth syndrome. However, it is also prevalent in extensively restored teeth.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses