Antoon De Laat

Sandro Palla

José Tadeu Tesseroli de Siqueira

Yoshiki Imamura

In this chapter, several cases are presented to illustrate various types of orofacial pain likely to be seen by dentists. After listening attentively to the patient’s complaints and taking a careful history, the clinician should be able to establish a provisional or differential diagnosis that will then be confirmed or rejected by a clinical examination, followed by appropriate tests and images if necessary, as outlined in chapter 17.

Case 1

Patient JS, a 38-year-old woman, complains of sharp, shooting, and irradiating pain of the left maxillary region that began suddenly one morning 3 weeks ago. She cannot localize the pain to a particular tooth. Now the pain is almost continuous at a level of 3 on a visual analog scale (VAS) of 1 to 10, with 10 being the worst. The pain is exacerbated when chewing on the left side and when drinking cold water, and it worsens (level 7) in the evening when she goes to bed. Last week, the pain kept her awake one night for more than 2 hours. She is aware of daytime episodes of clenching, plus her husband says that she grinds her teeth at night. No other oral parafunctional behaviors, such as nail biting or tongue thrust, are present. There is no history of facial or neck trauma. She does not report limitation of jaw movement or temporomandibular joint (TMJ) sounds.

Her past medical history is negative except for an appendectomy 10 years ago and sinus surgery 7 years ago due to chronic sinusitis. She has suffered from recurrent headaches, concomitant with menstrual periods and periods of stress, for several years. She takes no medication for these headaches. Her husband says she does not snore or cease breathing during sleep, and she does not complain of temporal headache on awakening, reducing the likelihood of a concomitant sleep breathing disorder.

Questions

What is your provisional or differential diagnosis? What kind of clinical examination is needed? What do you need to assess? What is the rationale?

Answers

Based on the onset, duration, and pattern of pain and exacerbating factors, dental or periodontal pathology should first be suspected. Careful intraoral and radiologic examinations will be necessary. In addition, tooth vitality testing and a local anesthesia challenge should help achieve final diagnosis. Considering the history of sinus surgery, presence of a maxillary sinusitis needs to be excluded. Here, a ra-diologic examination may help, but a consultation with an otorhinolaryngologist should be sought if sinusitis is suspected. Finally, in view of the history of sleep bruxism and wake-time clenching, TMJ and muscle pain needs to be excluded.

Clinical examination

Extraoral examination does not reveal any swelling, overt asymmetries, or peculiarities of the patient’s face. Facial expression and mandibular movements appear normal and without pain. Intraoral examination shows an Angle Class II, division 1 occlusion and no missing teeth but several amalgam fillings. There are no obvious carious lesions and no broken fillings. Functional examination reveals no apparent premature contacts. There is abrasion or attrition of the cusps of the canines and the occlusal surfaces of the premolars and molars. There is a slight gingivitis but no loss of gingival attachment.

Tooth vitality testing with an ice-cold stick (CO2 stick) is normal for all teeth in the second and third quadrants, but the patient displays a localized hypersensitivity of the maxillary left first premolar and second molar, as well as of the mandibular left second premolar. A provocation test, biting on a cotton roll or hard plastic stick between single pairs of teeth, provokes a sharp pain when the patient bites on the left second molars. No pain is induced upon mechanical percussion. Careful examination of the maxillary left second molar reveals no large filling or caries, but a fine crack in the buccopalatal direction is visible.

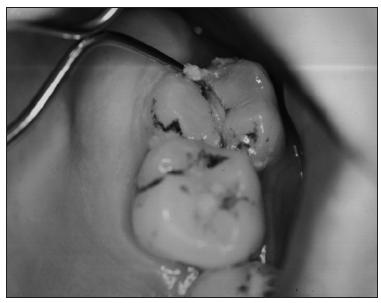

Panoramic and periapical radiographs of the maxillary left quadrant do not show any radiolucencies, carious lesions under old fillings, or periodontal problems. The fine crack is not visible on radiographs. The sinus in the vicinity of the maxillary left second molar appears normal on the panoramic radiograph. When a fine probe is forced between the two parts of the cracked tooth, a sharp pain is reported (Fig 27-1), which is eliminated by local anesthesia.

Fig 27-1 Cracked maxillary left second molar. A probe is forced between the two parts, which causes the patient to experience a sharp pain.

Working diagnosis

The working diagnosis is a cracked tooth, probably a result of severe and forceful wake-time bruxism of the clenching type and/or sleep clenching/grinding.

Discussion

The history and the character of the pain and its provocation by mastication, cold substances, and the probe test point to a dental etiology. There is a history of clenching habits, which could lead to some type of dental sensitivity, but this is typically less localized and tends to fluctuate over time. The past history of sinusitis and the localization of the pain in the maxillary region kept open the possibility of a maxillary sinusitis. The latter diagnosis is ruled out, however, because there is no recent history of a common cold, fever, blocked nose, or aggravation of the pain by head or bodily movements. For these reasons, the clinical examination focused on the oral cavity. If this examination had failed to show any abnormalities, a functional examination of the masticatory system (including palpation of the muscles and joints) would have been performed to check for temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) of myogenous origin and referred pain to the teeth. If no dental pathology or muscle pain had been found, the patient probably would have been referred to an otorhinolaryngologist.

The described pain is apparently caused initially by mechanical stimulation of tooth pulp nociceptors (see chapter 4). Inflammation has probably occurred gradually and has made the receptors hypersensitive to thermal and mechanical stimuli. After some time, the pain starts to radiate over the region (eg, left maxilla, muscles) because of central excitatory effects (see chapters 5 and 7).

Management

Since the fracture apparently extended into the root, the tooth was extracted (see chapter 20). To prevent damage to other teeth, a bite splint was fabricated for use during periods with stress and high clenching probability (see chapters 22 and 26).

Case 2

Patient AP, a 40-year-old male, has already consulted four dentists because of pain in the left mandible that has lasted more than 6 months. The third dentist thought it was related to the mandibular left second premolar, so he removed the pulp, which temporarily eliminated the pain. However, the pain recurred, and its intensity gradually increased to the pre-endodontic treatment level. The fourth dentist extracted the tooth some months later. Since that time, the patient still feels pain sometimes located in the spot where the tooth was extracted, but most of the time it is located in the mandibular left first premolar. The pain is now constant, dull, aching, and sometimes burning; it is rated 4 to 5 on a VAS of 1 to 10. He reports no pain during the night. Oral function (eg, chewing, talking), stress, or other factors do not exacerbate the pain. It increases slightly in the evening and when he is relaxed, watching television. Chewing gum relieves some of the pain. The patient has used several analgesics and is now taking up to six aspirin tablets per day with low to moderate relief.

His past medical history reveals that he has had a periodic left-sided headache for about 1 year. The headache periods started some time after he lost his job. He has been unemployed since then, which creates several psychosocial problems. During this period, his wife noticed more frequent tooth grinding during his sleep. More recently he has complained of chest pain, but he has not yet consulted his physician.

Questions

What will be the goal of the clinical and radiologic examination? What is your provisional or differential diagnosis?

Answers

In this particular case, the history and time course of the pain are not typical of a dental pathology, but first this should be excluded. The increase in severity of pain after the extraction, the character of the pain, and the relief brought about by chewing strongly suggest a diagnosis of atypical odon-talgia. However, referred pain from the masticatory muscles or from the cervical spine is also a possibility. Consequently, careful clinical and intraoral examination, radiographic examination, and perhaps referral to specialists (eg, neurologist, pain clinic) for differential diagnosis will be needed.

Clinical examination

The patient’s face looks normal in the extraoral examination, and intraorally there are no carious lesions, broken fillings, or periodontal pathology. The extraction site has hea/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses