CHAPTER 27. Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease is common and many patients with heart disease require dental treatment. Heart disease becomes more frequent and severe in later life and is the most frequent single cause of death in Britain. Younger patients can also be affected. Infective endocarditis is one of the few ways in which dental treatment can lead to death of a patient, but only very rarely. As mentioned earlier (Ch. 5), surveys have suggested that dental disease may possibly also contribute to the development of atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction, but though evidence is still being produced, the hypothesis is not widely accepted.

Acute angina and myocardial infarction are causes of major emergencies in the dental surgery and prompt measures by the dental surgeon may be life-saving (Ch. 36).

In terms of dental management, patients fall into two main groups (Box 27.1), but a few may fall into both; drug treatment may create additional problems (Table 27.1). It must be appreciated, therefore, that the following management suggestions are generalisations and each case must be considered on its own merits.

Box 27.1

Dental management in major types of heart disease

Valvular or related defects (congenital or due to past rheumatic fever) or who have a prosthetic replacement

• Prophylactic antibiotic cover, particularly before extractions, is mandatory

Ischaemic heart disease with or without severe hypertension and cardiac failure

• Routine dentistry presents little hazard, but the risk of dangerous arrhythmias must be minimised

• Local anaesthetics in normal dosage have only theoretical dangers, but pain and anxiety must be minimised

• The main risk is from general anaesthesia

| Drugs | Implications for dental management |

|---|---|

| Diuretics | Dry mouth sometimes |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, captopril, perindopril, etc. | Burning mouth symptoms, lichenoid reactions |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers, losartan, dysopyramide, etc. | Taste disturbance, dry mouth |

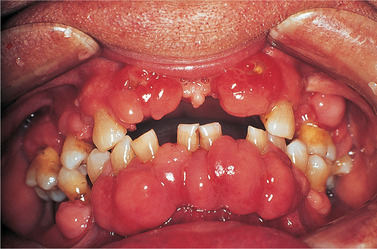

| Calcium channel blockers, amlodipine, diltiazem, etc. | Gingival hyperplasia (especially with diltiazem and nifedipine –Fig. 27.1) |

| Beta-adrenergic blockers, lobetalol, propranolol, etc. | Dry mouth, lichenoid reactions, theoretical interaction with epinephrine |

| Antihypertensives (as above) | Potentiated by general anaesthetics with reactions |

| Anticoagulants | Risk of prolonged postoperative bleeding |

| Warfarin | Risk of prolonged postoperative bleeding |

| Antianginal drugs | |

| Nicorandil | Aphthous-like stomatitis |

| Digoxin | Enhanced risk of dysrhythmias with halothane |

|

| Fig. 27.1

Drug-induced gingival hyperplasia resulting from treatment of hypertension with nifedipine. These swellings are centred on the interdental papillae.

|

GENERAL ASPECTS OF MANAGEMENT

Patients chiefly at risk are severe hypertensives and those who have angina or have had a myocardial infarct due to ischaemic heart disease. Anxiety or pain can cause outpouring of epinephrine which can both greatly increase the load on the heart and also precipitate dangerous dysrhythmias.

To die of fright is not a figure of speech but it can sometimes result from severe dysrhythmia. The first essential for these patients is therefore to ensure painless dentistry and to alleviate anxiety.

Patients should be asked whether routine dental treatment under local anaesthesia is acceptable and in any session of treatment as little or as much may be done as they feel able to tolerate.

Oral temazepam may be helpful (5 mg on the preceding night and again half an hour before treatment, and the patient accompanied by a responsible adult). If sedation is required, inhalational sedation is safer because nitrous oxide has no cardiorespiratory depressant effects and is more controllable, but it should be administered by an expert and not given within three months of a heart attack or recent angina.

Patients with severe or longstanding hypertension are at risk from ischaemic heart disease. Medical advice should be sought before treating those with blood pressures of 160–179/95–109. If considered at low risk from dental treatment, the same precautions should be taken for those with ischaemic heart disease.

Local anaesthesia for patients with cardiac disease

For local anaesthesia, an effective surface anaesthestic should be applied and the injection given very slowly to minimise pain. The most effective agent is 2% lidocaine with epinephrine and, after half a century of use, no local anaesthetic has been shown to be safer. The epinephrine content can theoretically cause a hypertensive reaction in patients receiving beta-blocker antihypertensives, because of an unopposed alpha-adrenergic effect. However, it is relevant that when an elderly woman receiving beta-blockers was given 16 cartridges (yes, really) of local anaesthetic with fatal results, the post-mortem conclusion was that she had died from lidocaine overdosage rather than exacerbated hypertension. This interaction is only likely if doses of epinephrine are considerably larger than normally used in dentistry.

Though patients with cardiovascular disease need to be treated with care, the risks of routine dental treatment under local anaesthesia (despite many statements to the contrary) and of significant adverse reactions are very low indeed.

In Britain, all three deaths associated with dental local anaesthesia during the 10 years 1980–1989 were related to the use of prilocaine. This does not, of course, mean that prilocaine is necessarily dangerous, but it hardly suggests that it is safer than the more widely used lidocaine with epinephrine.

Local anaesthetics can undoubtedly cause mild dysrhythmias, but it is not always appreciated that more severe dysrhythmias can be triggered by anxiety before they have been given, or later during the operation. However, doses of local anaesthetics should be kept to a minimum and no more than 2 or 3 cartridges should be given (or be necessary) for an acceptable session of treatment. If larger doses have to be given, for example for multiple extractions, then continuous cardiac monitoring is necessary.

If general anaesthesia is unavoidable, it must be given by a specialist anaesthetist in hospital, especially as some of the drugs used for cardiovascular disease increase the risks. Cardiovascular disease is the chief cause of sudden death under anaesthesia.

PATIENTS WITH VALVE OR OTHER HEART DEFECTS AT RISK FROM INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

Patients at risk are mainly those with congenital anomalies, such as valve or septal defects, or who have prosthetic heart valve replacements (Appendix 27.1). The majority of these patients have no symptoms and some valve defects, such as a bicuspid aortic valve, do not limit athletic activities.

Normally, bacteria entering the bloodstream are rapidly cleared by circulating leucocytes but, if there is a cardiac defect which can be colonised, infective endocarditis can develop.

There are many sources of bacteraemias, such as cardiac surgery, intravenous catheterisation and intravenous drug addiction. Bacteraemias can also be detected in over 80% of persons after extractions and even after toothbrushing, but the numbers of bacteria released are often very small. Even in a patient with a heart lesion, infective endocarditis does not necessarily follow.

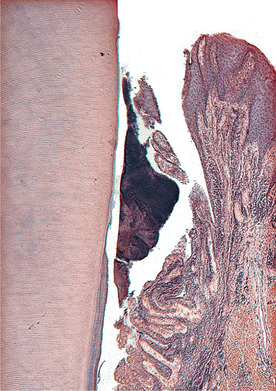

Relatively few bacteria inhabit the oral mucosa and most are being constantly washed away by the saliva. By contrast, vast numbers of bacteria inhabit the gingival margins when oral hygiene is poor and even greater numbers occupy periodontal pockets. These bacteria are in close contact with dilated, thin-walled blood vessels (Fig. 27.2). Movement of teeth in their sockets repeatedly compresses and stretches or ruptures these vessels, so that bacteria can be pumped into the bloodstream.

|

| Fig. 27.2

Subgingival plaque. The area of pocket wall in contact with plaque is large and the tissue contains numerous thin-walled blood vessels near the surface. This illustration serves to remind how easily microrganisms may be transferred into the circulation.

|

Fewer than 15% of cases of infective endocarditis can be related to (but not necessarily caused by) dental operations but, in these cases, extractions have been preceded by the infection in over 95%. Viridans streptococci, such as those which colonise the teeth, are of low virulence, but may be able to colonise heart valves because of attachment mechanisms (Ch. 3) which also enable them to cause dental disease.

Factors determining susceptibility to infective endocarditis are unclear. For example, children with Down’s syndrome – who are prone to severe periodontal disease, have multiple immune defects and, frequently, congenital cardiac defects – are not particularly susceptible to infective endocarditis.

Currently, advanced age, especially if there is periodontal sepsis, is the main risk factor (Fig. 27.3). Infective endocarditis is rare in children and the peak incidence and mortality is after the age of 60 years. For cardiac transplantation, patients are deeply immunosuppressed and might be considered to be at high risk of infective endocarditis after dental operations. However, data are limited and there is no agreed protocol for such patients.

|

| Fig. 27.3

Poor oral hygiene and severe pocketing such as this constitutes a risk to life, particularly in an elderly patient with a cardiac valve defect.

|

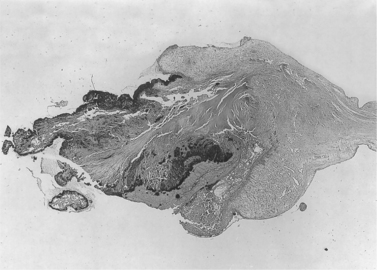

Once infective endocarditis develops, vegetations of bacteria and fibrin form on the valves, which are progressively destroyed (Fig. 27.4). Cardiac failure is the main cause of death, but emboli and bacteria released into the bloodstream can also cause renal or cerebral damage.

|

| Fig. 27.4

Heart valve in subacute infective endocarditis. The free edge of the valve lies to the left of the picture and is covered by vegetations; centrally the valve is inflamed and thickened; and to the right the normal thickness of the valve is seen, at its attachment to the heart.

|

Prevention is all important. Patients in high-risk categories should receive preventive advice and, if treatment becomes necessary, antibiotic prophylaxis (see below and Appendix 27.1) before treatment that disturbs the gingival margin. This is likely to release significant numbers of bacteria from the gingivae or, particularly, periodontal pockets. Other dental procedures, such as fitting metal bands which extend deep to the gingival margins, though they may cause bacteraemias, have rarely been followed by infective endocarditis and antibiotic cover has not been officially recommended in the past. However, if the clinician considers the patient to fall into a high-risk group, then it may be prudent to give cover. Otherwise, orthodontic procedures in general are not recommended for antibiotic cover, particularly because most of these patients are children in whom infective endocarditis is rare. Endodontic treatment rarely, if ever, leads to infective endocarditis and the risks of antibiotic prophylaxis exceed any benefits.

Infective endocarditis does not appear to be a risk after myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypasses, or for wearers of cardiac pacemakers, and antibiotic cover is not recommended for them.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses