23

Clinical Impact of Cone Beam Computed Tomography in Root Canal Treatment

Radiological examination is essential for diagnosis, treatment planning, management, and follow-up of endodontic disease. Until recently, this has been usually limited to two-dimensional periapical images. The interpretation of these images is difficult due to the limitations of its nature, where superimposition of the teeth and surrounding dentoalveolar structures reveals only limited aspects of the true three-dimensional configuration (Patel et al., 2007). Also, geometric distortion of the structures imaged is a common occurrence with conventional techniques (Grondahl and Huumonen, 2004). In consequence, essential images of the anatomy are not visible.

Clinical endodontics is heavily dependent on the ability of the practitioner to recognize and successfully deal with the complexities of root canal anatomy. An inability to detect, locate, and negotiate all root canals may lead to endodontic failure (Leonardo, 1998). As we know, anatomy varies significantly, even within the same tooth. A clear example is the mandibular first molar, the most endodontically treated tooth. Different studies show an incidence of a third root in around 13% of the cases. Three canals were present in 61.3%, 4 canals in 35.7%, and 5 canals in approximately 1%. Root canal configuration of the mesial root revealed 2 canals in 94.4% and 3 canals in 2.3%. The presence of isthmus communications averaged 54.8% on the mesial and 20.2% on the distal root (Valencia de Pablo et al., 2010).

With a chance of there being unusual and atypical root shapes and numbers, there is a need to look further into what a clinician can see or imagine with conventional radiography. In terms of clinical approach, it means that each tooth requiring endodontic treatment needs to be searched clinically for all its possible anatomical variations. This usually results in extensive removal of tooth structure.

These limitations have been overcome with the use of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) imaging, by providing high-quality three-dimensional views of the tooth and surrounding structures, with interrelational images in three orthogonal planes (axial, sagittal, and coronal). This enables the practitioner to visualize selected slices, evaluating endodontic anatomy and disease in a new way (Cotton et al., 2007). Most softwares provide multiplanar reformation (as oblique cross sections) useful for endodontic evaluation, where the reconstructed CBCT data can be reoriented and sectioned perpendicular to the plane of interest.

CBCT is changing the way the endodontic treatment is prepared and performed, as it has been validated as a tool to explore root canal anatomy. When reconstructions of root canal systems given by a CBCT (small field of view) equipment were compared with histological sections to evaluate the reliability of the reconstructions, strong to very strong correlation was found (Micheti et al., 2010). Small or limited field of view CBCT equipment are preferred for endodontic tasks because of the need for the highest possible resolution (less than 200 µm), the decreased radiation exposure to the patient, and to focus on the area of interest.

With high-resolution CBCT we are able to obtain a detailed identification of the root canal system, its variations, and anomalies; the position and size of the pulp chamber; calcifications; the number, position, size, extent, and curvatures of the roots and its canals; the tridimensional shape of each canal: whether it is round, oval, or has any other form at any specific level of the root; as well as the status of the surrounding bone.

All these information, combined with resources and technologies available in our field, such as magnification, increased illumination, ultraflexible instruments, and advanced irrigation have an impact on the approach and the procedures we use, as shown on the clinical cases that follow. They provide for significant smaller endodontic access cavities and more precise cleaning, shaping, and obturation maneuvers, preserving coronal and radicular tooth structure.

With the appropriate imaging technology, we should stop exploring every case searching for what “might be” in root canal anatomy and concentrate in what is “really present” in the tooth we are treating.

Case 1

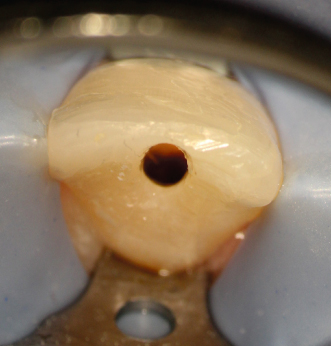

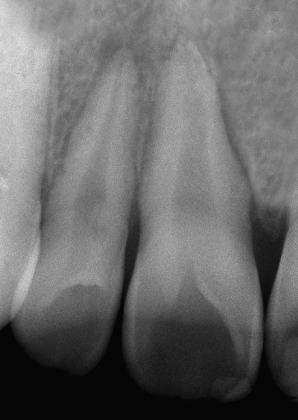

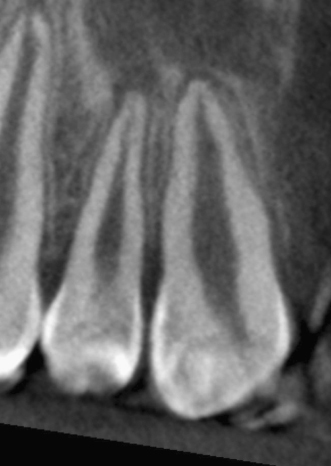

Maxillary central incisor, necrotic. Front clinical view (Figure 23.1), a fistula was present. Comparison between pretreatment periapical X-ray (Figure 23.2) and CBCT slices, coronal (Figure 23.3), axial (Figure 23.4), and sagittal (Figure 23.5). A more incisal access cavity, as suggested by the CBCT reconstruction (Figure 23.6) resulted in an improved straight line access (Figures 23.7 and 23.8). Calcium hydoxide placed between visits (Figures 23.9 and 23.10). Final preparation (Figure 23.11) and obturation (Figures 23.12 and 23.13). Appearance of the procedure on a periapical X-ray (Figure 23.14) and CBCT slices, coronal (Figure 23.15), axial (Figure 23.16), and sagittal (Figure 23.17). Restored tooth, no fistula (Figure 23.18) (restoration by Dr. Tomás Seif R., Caracas, Venezuela).

Figure 23.1 Front clinical view.

Figure 23.2 Pretreatment periapical X-ray.

Figure 23.3 Pretreatment coronal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.4 Pretreatment axial CBCT slice.

Figure 23.5 Pretreatment sagittal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.6 CBCT reconstruction.

Figure 23.11 Final preparation.

Figure 23.14 Appearance of the procedure on periapical X-ray.

Figure 23.15 Appearance of the procedure on coronal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.16 Appearance of the procedure on axial CBCT slice.

Figure 23.17 Appearance of the procedure on sagittal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.18 Restored tooth, no fistula.

Case 2

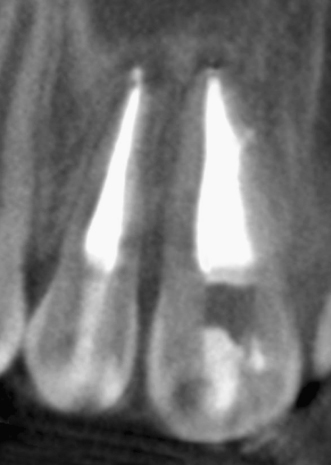

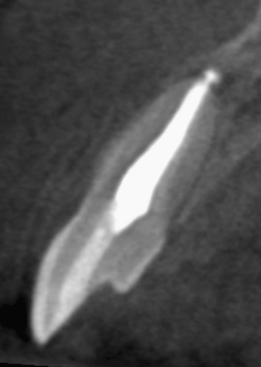

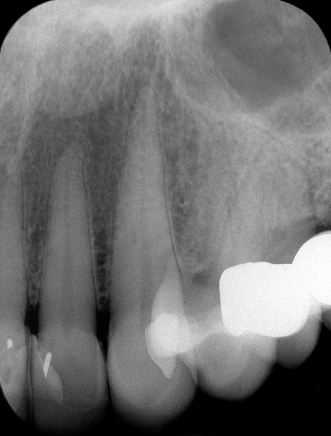

Maxillary central and lateral incisors, necrotic, trauma. As seen on pretreatment panoramic X-ray (Figure 23.19), periapical X-ray (Figure 23.20), and CBCT slices, coronal (Figure 23.21), axial (Figure 23.22), and sagittal (Figure 23.23 for the central incisor, Figure 23.24 for the lateral incisor). Note the unusual shapes of the canals, suggested on the X-ray but clearly seen on the CBCT slices. Appearance of the procedure on a periapical X-ray (Figure 23.25) and CBCT slices, coronal (Figure 23.26), axial (Figure 23.27), and sagittal (Figure 23.28 for the central incisor, Figure 23.29 for the lateral incisor).

Figure 23.19 Pretreatment panoramic X-ray of maxillary central and lateral incisors, necrotic, trauma.

Figure 23.20 Pretreatment periapical X-ray.

Figure 23.21 Pretreatment coronal CBCT slice.

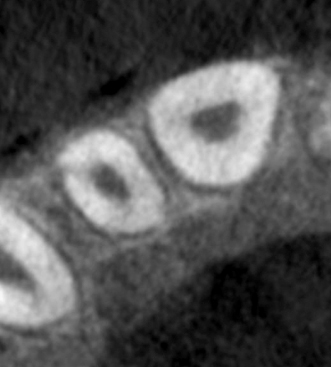

Figure 23.22 Pretreatment axial CBCT slice.

Figure 23.23 Pretreatment sagittal CBCT slice of central incisor.

Figure 23.24 Pretreatment sagittal CBCT slice of the lateral incisor.

Figure 23.25 Appearance of the procedure on a periapical X-ray.

Figure 23.26 Appearance of the procedure on coronal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.27 Appearance of the procedure on axial CBCT slice.

Figure 23.28 Appearance of the procedure on sagittal CBCT slice of the central incisor.

Figure 23.29 Appearance of the procedure on sagittal CBCT slice of the lateral incisor.

Case 3

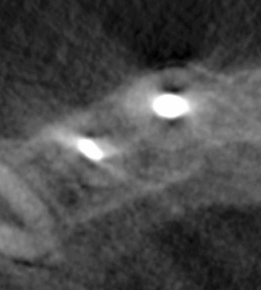

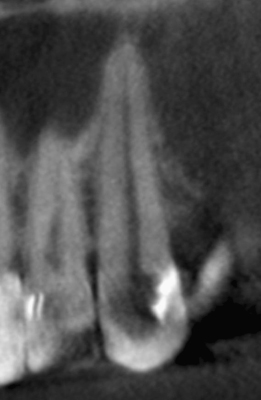

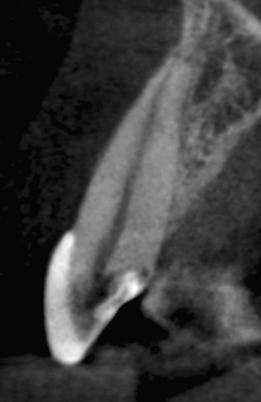

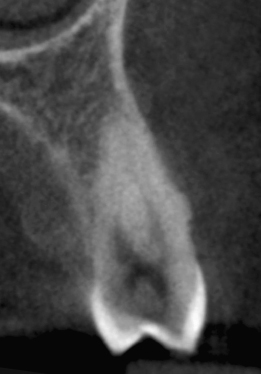

Maxillary canine, irreversible pulpitis. As seen on pretreatment panoramic X-ray (Figure 23.30), periapical X-ray (Figure 23.31), and CBCT slices, coronal (Figure 23.32), sagittal (Figure 23.33), and axial (Figure 23.34). Appearance of the procedure on a panoramic X-ray (Figure 23.35), periapical X-ray (Figure 23.36), and CBCT slices, coronal (Figure 23.37), sagittal (Figure 23.38), and axial (Figure 23.39). Again, a more incisal approach results in tooth structure preservation.

Figure 23.30 Pretreatment panoramic X-ray.

Figure 23.31 Appearance of the procedure on a panoramic X-ray.

Figure 23.32 Pretreatment periapical X-ray.

Figure 23.33 Case 3: Pretreatment coronal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.34 Pretreatment sagittal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.35 Pretreatment axial CBCT slice.

Figure 23.36 Appearance of the procedure on a periapical X-ray.

Figure 23.37 Appearance of the procedure on coronal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.38 Appearance of the procedure on sagittal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.39 Appearance of the procedure on axial CBCT slice.

Case 4

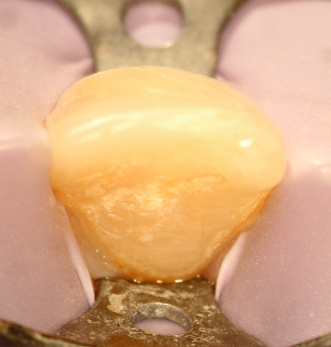

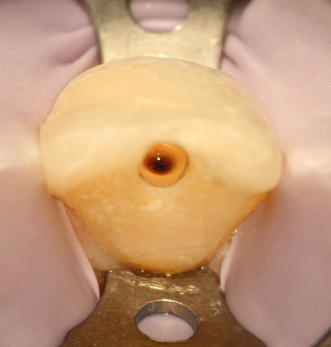

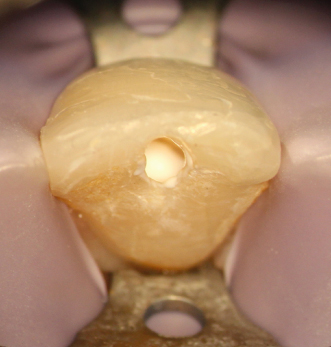

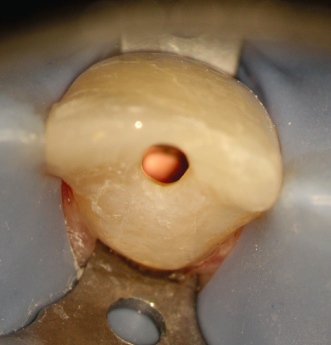

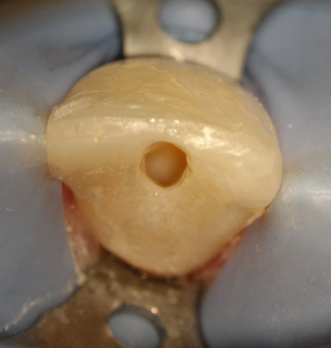

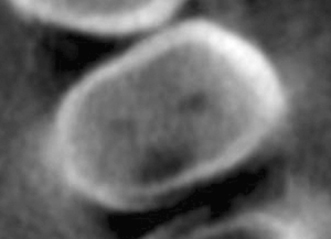

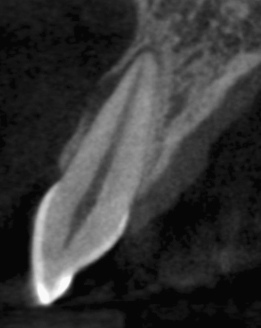

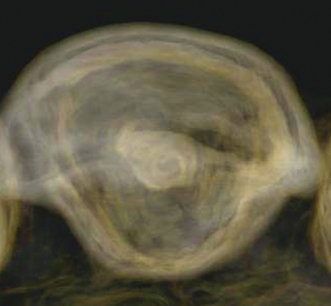

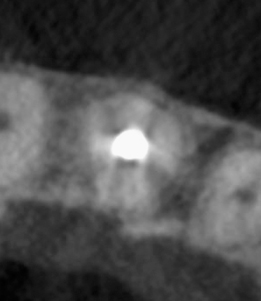

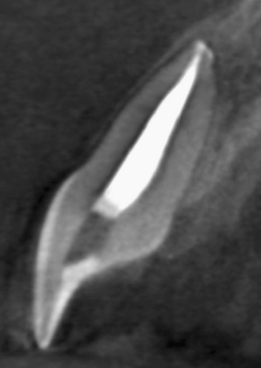

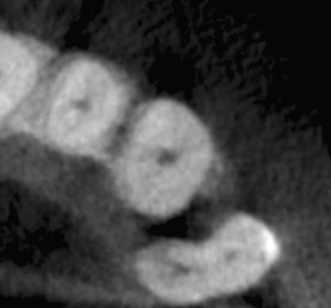

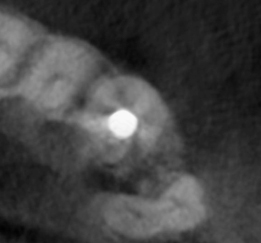

Maxillary first bicuspid, irreversible pulpitis, caries. Comparison between pretreatment periapical X-ray (Figure 23.40) and CBCT slices, sagittal (Figure 23.41), axial, different levels (Figures 23.42–23.44), and coronal (Figure 23.45). Clinical approach: Isolation (Figure 23.46) CBCT reconstruction, occlusal view (Figure 23.47). Outline of a conventional approach as suggested for the location of the canals (Figure 23.48). Actual approach (Figures 23.49 and 23.50). Comparison on the outline of the conventional approach and the actual approach (Figure 23.51). This reduced access cavity impedes the simultaneous views and handling of both canals; however, it is enough for accessing as single canals. Occlusal view of the buccal canal (Figure 23.52) and palatal canal (Figure 23.53). Obturation (Figures 23.54–23.56). Restored tooth (Figure 23.57) (restoration by Dr. Tomás Seif R., Caracas, Venezuela). Appearance of the procedure on a periapical X-ray (Figure 23.58) and CBCT slices, axial, different levels (Figures 23.59 and 23.60), and coronal (Figure 23.61)

Figure 23.40 Pretreatment periapical X-ray.

Figure 23.41 Pretreatment sagittal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.45 Pretreatment coronal CBCT slice.

Figure 23.46 Isolation.