21

Health Behavior and Dental Care of Diabetics

- To achieve good health behavior in oral and diabetes care, collaboration between diabetic patient, dentist, and other medical professionals is highly recommended.

- There is a bidirectional link between diabetes and periodontal infection: periodontitis might have a negative impact on metabolic control and progression of complications, while poorly controlled diabetes and diabetic complications increase the risk of periodontal infections.

- Prevention and early diagnosis of periodontal diseases are important goals for diabetic patients, especially for children, adolescents, and patients with poor metabolic balance and complications.

- The goal of treatment is to eliminate periodontal infection/inflammation effectively. Regular maintenance care is important to minimize the risks to general health.

- Dentist should be aware of the special features in the treatment of diabetic patients, such as how to handle emergency situations, the need for sterile, antitraumatic treatment, and the use of prophylactic antibiotics.

Introduction

There are about 150 million people with diabetes mellitus. The number is expected to rise to 300 million by the year 2025. In particular, the prevalence of type II diabetes is rapidly increasing, and it also involves young patients. Diabetes mellitus and related complications in the eyes, kidneys, heart, blood vessels, and nerves affect the patients’ quality of life, demand considerable medical resources and causes morbidity. Thus, the effects of diabetes on both a personal level and in the economy as a whole will grow significantly in the future.

It has been shown that oral diseases are associated with diabetes mellitus (Lakschevitz et al., 2011; Lalla & Papapanou, 2011). Diabetic patients have a 2–3 times greater risk of suffering from periodontal disease than nondiabetics (Marigo et al., 2011), and it has been found that diabetics are about 5 times more likely to be partially edentulous than controls (Moore et al., 1998). Diabetics also have a higher risk of xerostomia and oral mucosal lesions, and they may have impaired wound healing. On the other hand, the relationship is postulated to be bidirectional: periodontitis as a chronic infection might impair metabolic control and increase risk of renal complications (Shultis et al., 2007).

Several plausible biological mechanisms have been presented to explain the observed connection between diabetes and oral health. Nonenzymatic formation of advanced glycation end products predispose to many cell and tissue changes, for example, changes in inflammation response and collagen metabolism. In addition to a causal link brought about by biological mechanisms, it is possible that part of the association is coincidental, which means there might be risk factors in common, such as smoking and other lifestyle factors. Similarly, common psychological factors which affect health behavior in dental and diabetes self-care can give significant insight into the relationship between diabetes and oral health.

Knowledge about oral diseases among diabetic patients is poor (Sandberg, Sundberg, & Wikblad, 2001; Yuen et al., 2009). Good self-care is essential to maintain a good state of health, and therefore, every effort must be made to remove obstacles to optimal self-care. Diabetic patients require regular checkups and special attention by dental professionals. In order to have an impact on the behavioral aspects of diabetic patients’ self-care practices, the whole dental appointment situation should be made safe and confidential. This means that dentists must be able to assess and prevent medical risks for diabetics as dental patients. To ensure good healthcare results, dental professionals need to be conscious of the special needs of diabetics as dental patients. On the whole, close collaboration between diabetics, dental practitioners, and other healthcare professionals is called for. This would allow them to share the responsibility for good health behavior in oral care and diabetes, making it possible to understand that oral health is an integral part of general health.

Diabetes Mellitus and Oral Diseases

Several studies have shown that more gingival bleeding, more sites with pathological periodontal pockets, and extensive alveolar bone loss is found in diabetic patients than in nondiabetics. However, diabetics form a very heterogenic group, and it is therefore important to recognize those diabetic features which, as risk indicators, determine the association between diabetes and oral health.

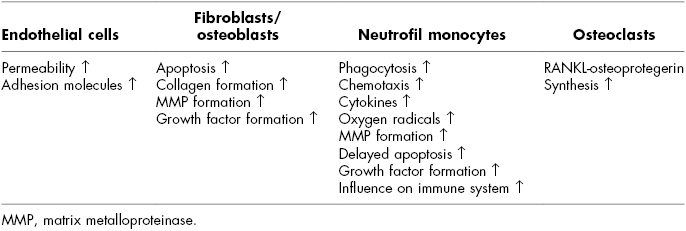

Researches have shown that poor metabolic control (Tsai, Hayes, & Taylor, 2002), long duration of disease (Hugoson et al., 1989), and diabetic organ complications (Tervonen & Karjalainen, 1997) seem to be significant in making periodontal disease worse. Metabolic syndrome is a predisposing disease to type II diabetes, and recent studies have also shown a view of connection between metabolic syndrome and periodontitis (Morita et al., 2010; Timonen et al., 2010) and also between insulin resistance and periodontal diseases (Benguigui et al., 2010; Timonen et al., 2011). The predisposing influence of diabetes to periodontitis has even been found among children (Lalla et al., 2007). Furthermore, it has been proposed that a number of diabetes-related biologic changes can also increase the risk of periodontitis. These are impairment of polymorphonuclear leukocyte function, decrease in collagen synthesis, and increase in glycosylated proteins, proinflammatory cytokines, as well as collagenase activity (Soskolne, 1998; Lalla et al., 2000). The effects of hyperglycemia on periodontal disease at the cell level are shown in Table 21.1.

Table 21.1 Mechanisms of Hyperglycemia Affecting Periodontal Disease at the Cell Level

Diabetes mellitus leads to a hyperinflammatory response in the periodontal microbiota and impairs repairing processes. Important cytokines in this inflammation progress are, for example, IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-alfa. There is evidence of weakly controlled patients who show high levels of interleukin-1beta, which together with the prolonged expression of tumor necrosis factor could cause major damage during an inflammation process (Marigo et al., 2011). A positive relation between periodontal inflammation and glycemia has been found, and moreover, glucose accumulation in crevicular fluid may cause an increase in spirochetes and bacteria. However, no significant differences in the level of periopathogens between diabetics and nondiabetics has been found.

The interrelationship between diabetes and periodontal diseases is bidirectional, as observed in the introduction. It has been shown that periodontal treatment affects metabolic control and thus leads to better general health in diabetics (Wijnand, Gerdes, & Loos, 2010). However, this positive effect of periodontal treatment is more manifest among type II than type I diabetics. There is also light evidence that periodontitis might be one risk factor in the incidence of type II diabetes (Demmer, Jacobs, & Desvarieux, 2008).

Whether diabetics have an increased risk of dental caries is not clear. Studies are highly controversial: some have found a higher occurrence of caries among diabetics than nondiabetics, while others show no difference between the two groups, and some studies have even found less caries among diabetics than nondiabetics (Sampaio, Mello, & Alves, 2011). A poor metabolic control has been found to be associated with a high rate of caries (Siudikiene, Maciulskiene & Nedzelskiene, 2005; Bakhshandeh et al., 2008; Miko et al., 2010). In another study, instead, metabolic control was not associated with dental caries, but it strengthened the positive association of mutans streptococci and lactobacilli with dental caries (Syrjälä et al., 2003). However, it is worth bearing in mind that poor metabolic control, salivary gland hypofunction, and high crevicular fluid glucose concentrations may increase the risk of dental caries in diabetics. On the other hand, lower caries prevalence among diabetics has been explained by a sucrose-restricted diet and regular eating. Nowadays, though, diet is no longer as restricted as before because insulin can be administered more flexibly, and blood glucose can be monitored regularly.

Other oral diseases related to diabetes are xerostomia and fungal infections. Poor glycemic control can cause xerostomia, which increase the risk of candidiasis. Xerostomia can also change the protein composition of saliva and cause parotid swelling (Soell et al., 2007). An increased risk of oral mucosal lesions has also been observed, such as fissured tongue, median rhomboid glossitis, irritation fibromas, traumatic ulcers, oral leukoplakia, and lichen planus among diabetics. A link between diabetes and taste impairment and burning mouth syndrome has also been suggested. All in all, comprehensive evaluation of salivary function as well as detection and treatment of oral manifestations are important among diabetic patients.

Health Behavior

Oral Health Behavior

The main etiological factor for periodontal diseases is microbial dental plaque with a biofilm structure. It has been demonstrated that sustained, effective plaque control by the patients themselves is effective in preventing periodontal disease. This should include tooth brushing twice a day and interdental cleaning at least once a day. However, supragingival plaque control alone is not sufficient. It is also necessary to have a professional mechanically remove subgingival biofilm and dental calculus. In other words, it is essential to control plaque levels and ensure regular dental maintenance to prevent and treat periodontal diseases. It is also highly recommended that smoking stops when preventing and treating periodontal diseases.

As far as dental caries is concerned, microbial plaque and sugar in the diet are two major etiological factors. Therefore, toothbrushing twice a day with fluoride toothpaste and avoiding sugar are effective ways of preventing dental caries. Furthermore, the use of other fluoride and xylitol products is beneficial in preventing caries especially among high-risk individuals.

It has been found that diabetic patients are not particularly aware of the increased risk of oral diseases and that their attitude towards maintaining good oral health is poor (Eldarrat, 2011). Dental professionals should therefore ensure that diabetic patients are given proper information about the relationship between diabetes and oral health. It is also necessary to improve skills in performing oral hygiene practices because a higher incidence of plaque has been detected among diabetics than nondiabetics (Bridges et al., 1996; Sandberg et al., 2000; Arrieta-Blanco et al., 2003).

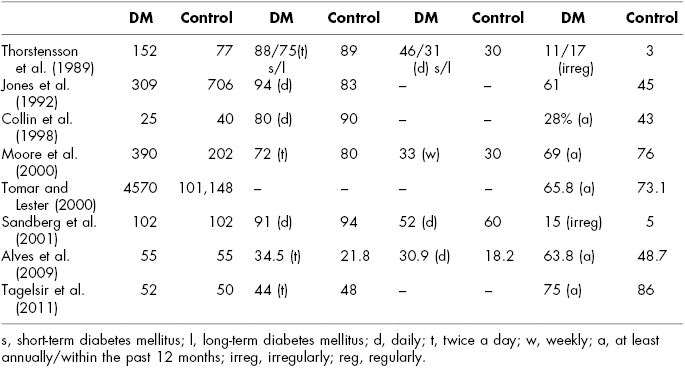

A number of studies have compared oral health behavior between diabetic and nondiabetic patients, but only a few have included all self-care practices, and also the criteria for good oral health behavior vary. There is also an abundance of descriptive studies on oral health behavior that include only diabetic patients. Comparisons between different studies are therefore difficult to make, but the results presented in Table 21.2 give a general idea of oral health behavior among diabetics compared to nondiabetic controls.

Table 21.2 Oral Health Behaviors among Diabetes Mellitus Patients Compared to Nondiabetic Controls

According to most of the studies, there are no major differences in oral self-care practices between diabetics and nondiabetics. Daily tooth brushing seems to be quite usual in both groups while brushing twice a day and daily interdental cleaning are irregular habits. There were differences in how regularly diabetics visit the dentist, though, showing more problems with attendance. It has been found that diabetics tend to miss dental appointments more often (Pohjamo et al., 1995) and require more emergency dental care (Thorstensson et al., 1989; Rahim-Williams et al., 2010) than nondiabetics. In addition, IDDM patients with poor metabolic control or diabetes-related complications visit the dentist less regularly than other diabetics (Karjalainen, Knuuttila, & von Dickhoff, 1994). It has been observed that while diabetics regularly visit the diabetes clinic, there were problems with the recommended dental treatment visits (Karikoski, Ilanne-Parikka, & Murtomaa, 2003).

Oral health information and demonstration of oral hygiene techniques should be included in diabetes self-management programs. Differences in content have been found between different education programs, with 10–15% of all programs not providing any oral health information and only 10% included a demonstration on oral hygiene techniques (Yuen et al., 2010). In conclusion, improved oral health behavior is needed among all of diabetics, and it should focus especially on patients with poor metabolic control and complications. Discussion about oral health behavior should be included as a part of other medical self-care issues and similarly also in connection of diabetes controls.

Diabetes Health Behavior

The purpose of daily self-care is to keep the level of blood glucose as close to normoglycemia as possible. Patients’ self-care practices are indeed a crucial part in ensuring good metabolic control. Poor self-care causes poor long-term metabolic control, and this may predispose to the development of diabetic complications. These consist of microangiopathic complications, such as retinopathy and nephropathy, neuropathy, and a variety of macrovascular changes due to arteriosclerosis. This, in turn, increases the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and gangrenes. Periodontal disease has also been regarded as one of the complications of diabetes.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (1993) has shown that optimal blood glucose control delays and prevents diabetic complications. Numerous studies have found that better adherence is associated with improved glycemic control and decreased healthcare resource utilization (Asche, LaFleur, & Conner, 2011). It has been shown that infrequent attenders have more complications and poorer metabolic balance than regularly visiting patients (Griffin, 1998). The occurrence of missed diabetes control appointments varies considerably between studies, from 4% to 40%. Nevertheless, there is also evidence that appropriate self-care does not always guarantee a good metabolic balance, for example, due to differences in insulin absorption, insulin sensitivity, exercise, stress, food absorption, hormonal changes, illnesses, and traveling (American Diabetes Association, 1998a,b).

We recommend the article “Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2012” (American Diabetes Association, 2012) to the reader. It provides a comprehensive range of recommendations, including screening, diagnostic, and therapeutic actions for diabetics. Medical care should be organized by a physician-coordinated team, with an approach that assumes individuals with diabetes to take an active role in their self-care. Diabetes self-care practices consist of the following parts, which will be useful for dentists to know too:

- Insulin therapy

Type I diabetes: multiple-dose insulin injections three to four times per day or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. Insulin is matched to carbohydrate intake, premeal blood glucose, and anticipated activity.

Type II diabetes: initiation of oral agent therapy along with lifestyle interventions. Also insulin therapy is added into medication in some cases. - Assessment of glycemic control

Self-monitoring by means of blood glucose is useful as a guide to management of diabetes. Interstitial glucose A1C should be performed according to the treatment plan. For the majority of adult patients, a reasonable goal for A1C is <7%. - Medical nutrition therapy

The mix of carbohydrate, protein, and fat is adjusted to meet metabolic goals and individual preferences. Monitoring of carbohydrates is a key strategy in achieving glycemic control, and furthermore, alcohol use should be limited. - Physical activity and smoking cessation

Diabetics are advised to perform regular aerobic physical activity. It is highly recommended that they stop smoking. - Regular foot care examinations

Foot examinations should be performed annually, including inspection, assessment of foot pulses, and testing for loss of protective sensa/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses