Granulomatous Diseases

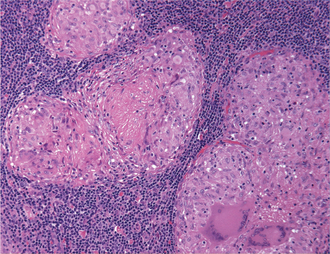

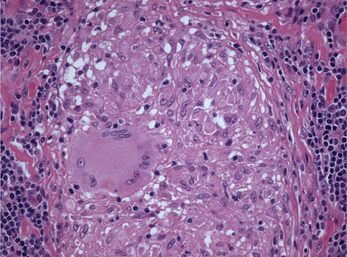

A granuloma is a focal aggregate of inflammatory cells, composed predominantly of epithelioid macrophages, which may be surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes and/or plasma cells. Epithelioid macrophages resemble epithelial cells, having abundant pale pink cytoplasm, vesicular and oval nuclei and indistinct cell borders (Figure 1). Some activated macrophages may fuse to form multinucleated giant cells which may be located within the center or periphery of the granuloma (Figure 2). In Langhans type giant cells the nuclei are arranged in the periphery, often in the shape of a horseshoe. The nuclei of foreign body type giant cells are arranged haphazardly in the cytoplasm. Some granulomas may show central areas of necrosis. Caseous necrosis, in which the dead tissue is soft and dry and resembles cheese, is classically associated with tuberculosis. Long-standing granulomas may be surrounded by a rim of fibrous connective tissue and fibroblasts.

Figure 1 Photomicrograph of a granulomatous inflammatory reaction showing multiple granulomas surrounded by lymphocytes. Each granuloma is composed predominantly of epithelioid macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. Epithelioid macrophages show abundant pale pink cytoplasm, vesicular and oval nuclei and indistinct cell borders. (Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification 200x)

Figure 2 Photomicrograph showing a multinucleated giant cell in the center of a granuloma. The nuclei of the giant cell are arranged in the periphery of the cytoplasm. (Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification 250x)

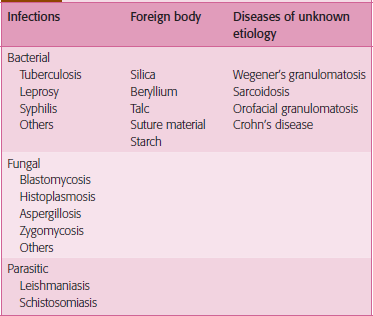

Granulomas can be classified as immune or foreign body type. Foreign body type granulomas develop in response to inert endogenous or exogenous foreign material (Table 1). Immune-mediated granulomatous inflammation represents a form of delayed type (cell-mediated) hypersensitivity reaction and may be secondary to specific types of bacterial, fungal and parasitic infections. Immune granulomas are mostly seen with mycobacterial and fungal infections because the infectious organisms typically have antigens which are poorly degraded by macrophages. Antigen exposure initiates a cell-mediated immune response, resulting in activated CD4+ T lymphocytes of the Th1 type which secrete cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-2, IL-12, interferon (IFN)-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. The cytokines stimulate activation of macrophages to form granulomas. Some immune-mediated granulomatous diseases are of unknown etiology (Table 1).

Tuberculosis

Pathogenesis

The disease is usually transmitted by the airborne spread of droplet nuclei produced by patients with infectious pulmonary tuberculosis. Droplets aerosolized by coughing, sneezing or speaking are inhaled. Thus transmission of infection is enhanced by crowded conditions in poorly ventilated rooms and prolonged, close contact with patients with active tuberculosis. Inhaled bacilli reaching the alveoli are ingested by non-specifically activated alveolar macrophages, which may contain the bacillary multiplication or be killed by the multiplying bacilli. Chemotactic factors released by lysed macrophages attract non-activated monocytes from the bloodstream to the site. These initial stages of infection are usually asymptomatic.

Clinical features

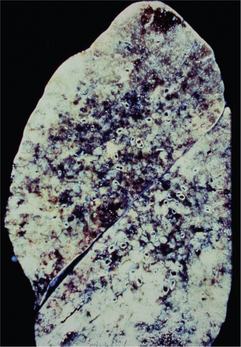

Tuberculosis is classified as pulmonary or extrapulmonary. Pulmonary tuberculosis can be primary or secondary. Primary pulmonary disease results from an initial infection with M. tuberculosis in previously unexposed individuals and is usually asymptomatic. The lesion is usually peripheral and localized to the middle and lower lung zones and is accompanied by hilar or paratracheal lymphadenopathy. In most cases, the lesion heals spontaneously and may later be evident as a small calcified nodule (Ghon lesion) (Figure 3). Approximately 5–10% of patients progress directly from initial infection to active disease, usually because of an existing state of immunosuppression. This is especially seen in children and in persons with impaired immunity, such as those with malnutrition or HIV infection. The initial lesion enlarges, cavitates, invades and destroys bronchial walls and blood vessels. Large numbers of bacilli spread into the airways and the environment through expectorated sputum. Patients may develop pleural effusion and progressive primary tuberculosis. Hematogeneous dissemination may result in fatal miliary tuberculosis (Figure 4) or tuberculous meningitis.

Figure 3 Gross appearance of Ghon lesion in the lung of a patient with a history of healed primary pulmonary tuberculosis. It presents as a calcified spherical mass

Secondary pulmonary tuberculosis, also known as post-primary disease, is usually due to endogenous reactivation of latent infection. Triggers for reactivation include immunosuppression, especially AIDS, malnutrition and vitamin D deficiency. The disease usually occurs in the apical and posterior segments of the upper lung lobes, where the high oxygen tension favors mycobacterial growth. The extent of lung involvement varies greatly, from small infiltrates to extensive cavitatory disease. Massive involvement of the lungs, with coalescence of lesions, produces tuberculous pneumonia. The result may be death, spontaneous remission or chronic disease with a progressively debilitating course (‘consumption’). Individuals with chronic disease continue to discharge tubercle bacilli into the environment. Symptoms and signs are often non-specific and insidious early in the course of secondary pulmonary tuberculosis, consisting mainly of fever, night sweats, weight loss, anorexia, general malaise and weakness. Cough eventually develops in most individuals, often initially non-productive and subsequently accompanied by the production of purulent sputum. The sputum may be blood-streaked due to blood vessel involvement.

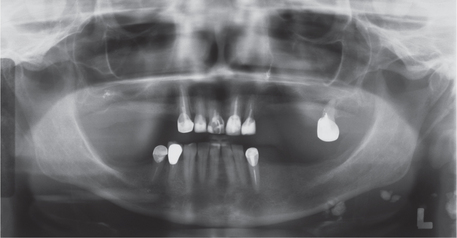

Lymph node tuberculosis (tuberculous lymphadenitis) is the most common form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis and is especially common in HIV-infected persons. It usually presents as painless swelling of the lymph nodes, most commonly at cervical and supraclavicular sites (scrofula). Lymph nodes are usually discrete in early disease but may develop caseous necrosis and form fistulas through the overlying skin draining caseous material. Involved nodes may radiographically appear calcified (Figure 5). Pulmonary tuberculosis is unusual in patients with scrofula.

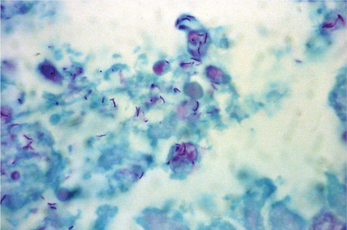

Histopathologic features

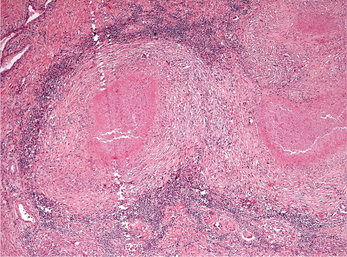

Affected tissues show multiple granulomas called tubercles which consist of aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes, lymphocytes and Langhans multinucleated giant cells (Figure 1). The tubercles often show central caseous necrosis (Figure 6). Special stains such as Ziehl-Neelsen or other acid-fast stains are required to demonstrate the bacteria (Figure 7). Because of the relative scarcity of bacilli within tissue, organisms may not be successfully demonstrated in all cases, and a negative result therefore does not completely eliminate the possibility of tuberculosis.

Figure 6 Photomicrograph of a caseating granuloma from a tuberculous lesion. The center of the granulomas shows caseous necrosis. Multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes are seen in the periphery of the granuloma. (Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification 5x)

Diagnosis and laboratory findings

A presumptive diagnosis of active tuberculosis is commonly made on the finding of acid-fast bacilli on microscopic examination of a diagnostic specimen such as a tissue biopsy or a smear of expectorated sputum. Definitive diagnosis requires the isolation and identification of M. tuberculosis from a diagnostic specimen, usually sputum in a patient with productive cough. Specimens are cultured on egg- or agar-based medium and incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2. The organisms grow slowly in culture and 4–8 weeks may be required before growth is detected.

Automated liquid culture systems are faster and show a greater yield than solid media-based systems.

Management protocols and prognosis

Strategies for prevention and disease control include BCG vaccination and treatment of persons with latent tuberculosis infection who are at high risk of developing active disease, such as those infected with HIV, close contacts of persons with known or suspected active tuberculosis, persons with medical risk factors associated with reactivation of tuberculosis, medically underserved and low-income populations, alcoholics, injection drug users, persons with abnormal chest radiographs compatible with past tuberculosis, and residents of long-term care facilities. BCG vaccine is recommended for routine use at birth in countries with high tuberculosis prevalence. However, general use of BCG may not be recommended in countries with low risk of transmission due to the wide variation in efficacy of the vaccines available.

Leprosy (Hansen’s Disease)

Clinical features

Tuberculoid leprosy, which corresponds to the pauci-bacillary form of the disease, presents initially on the skin as hypopigmented, well-demarcated macules that enlarge slowly and develop elevated margins. The number of lesions is usually limited. Loss of dermal appendages (hair follicles and sweat glands) also is seen, especially in fully developed skin lesions. Nerve involvement occurs early in the course of the disease and sensory, motor and autonomic nerves are affected, with resulting hypoesthesia, muscle weakness and anhidrosis. Involved nerves are enlarged and can be visible clinically. Some patients can present with severe painful neuritis. Sensory loss in the hands and feet often leads to severe trauma and burns. When the facial nerve is affected, patients can experience lagophthalmos (inability to close eyelids completely) and facial paralysis. When the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve is involved, anesthesia of the cornea and conjunctiva can increase the risk of corneal trauma and ulceration. These ocular lesions can result in blindness.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses