20

Biopsychosocial Considerations in Geriatric Dentistry

- Biologically advanced age modulates neuroendocrine and immunologic pathways at the cellular and molecular level over the course of life.

- Oral disease is, by and large, a chronic inflammatory process that affects the systemic health.

- Oral-systemic conditions are influenced by psychosocial influences.

- Behavioral risk factors modulated by psychosocial dynamics have adverse effects on specific physiological determinants of health.

- Chronic disease prevention requires interprofessional risk assessment and intervention.

Introduction

Shifts in global demographics’ increased life expectancies are a well-documented phenomenona and are humanity’s most astonishing biomedical and psychosocial triumphs. These phenomena are directly related to biomedical advances that improve overall health as well as societal/behavioral changes that include a healthier diet, greater social engagement, and increased level of physical activity. The elderly (65+ years old) are involved in volunteerism, travel, educational pursuits, and are a reservoir of experienced workforce. The increase in the proportion of the elderly in the overall population will impact the socioeconomic fabric of society and influence international political agendas. Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean are projected to experience a dramatic growth in the number of elderly, whereas, Europe, China, and India are expected to experience a population growth of octogenarians (80+ years old) (HelpAge International, 2010; Global Health and Aging, n.d.).

Similarly, the United States is experiencing a shift in demographics as the baby boomers turn 65 years of age and the number of the elderly is projected to triple to almost 90 million by 2060. The elderly over the age of 80 years are expected to double, representing over 20% of the population by 2030. Environmental, lifestyle, behavioral improvements, socioeconomic prosperity, genetic endowment, and efficient therapeutic regimens have extended life expectancy (Murphy & Hepworth, 1996; Cutler, Glaeser, & Rosen, 2007). Yet, the majority of Medicare recipients are diagnosed with one or more noncommunicable lifestyle-related chronic systemic (Table 20.1) condition with associated comorbidities that affect their quality of life, loss of autonomy, and increased healthcare costs (Kass-Bartelmes & Bosco, 2002; Keehan et al., 2012). Modern technological advancements and polypharmaceutical interventions have transformed once fatal diseases into chronic conditions expressed later in life that exacerbate oral manifestations (Ciancio, 2004; Cherry, Lucas, & Decker, 2010).

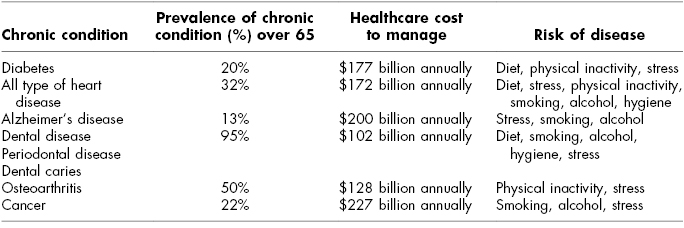

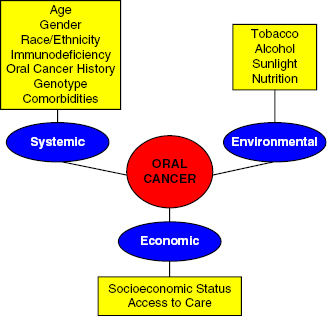

Table 20.1 Noncommunicable Lifestyle Chronic Conditions

While some elders are facing longer and more active lives, some elders experience functional decline, often inevitable with onset of chronic conditions, affecting activities of daily living (ADL), such as eating, bathing, and dressing, and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), such as grocery shopping, preparing meals, and taking medication, which further increase the risks of isolation, depression, and suicide (National Institute of Mental Health, 2003). The elderly are also challenged by geriatric syndromes, which are a unique interaction of pathogenic pathways, multifactorial etiologies that develop as an atypical single clinical symptom (i.e., delirium, frailty, incontinence), and does not fit traditional disease system categories (Walston et al., 2006). The synergistic effect of advanced age, cognitive, functional decline, and psychosocial risk factors challenge the elderly and caregivers, and increase the degree of stress exerted on the healthcare system (Evarard et al., 2000; Inouye et al., 2007). Chronic conditions presented by the elderly involve multiorgan systems that cross discipline-based boundaries. Healthcare management requires coordinated patient-directed interprofessional care.

Most chronic systemic conditions and oral disease share common lifestyle modifiable risk factors mediated by genetic, environmental, behavioral, and socioeconomic factors (Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2000; Paquette, 2002; Seymour et al., 2007; Oral Health America, 2003). Oral health is one domain of health that can affect general health, including emotional, psychosocial, and functional well-being (Ciancio, 2004; Kandelman, Petersen, & Ueda, 2008; Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2000). The oral cavity is a well-balanced ecosystem that harbors diverse bacterial species in high-density biofilm. Lifestyle habits, environmental disparities, as well as host response to bacterial accumulation on the hard and soft oral tissues may contribute to an inflammatory response not directly associated with chronological age (Fitzgerald, 1968; Keyes, 1968). Ninety-eight percent of the population is challenged by diseases of the oral cavity (Bomberg & Ernst, 1986). Traditional medical care promotes crisis intervention and does not generally cater to the heterogeneity of oral-systemic diseases in the elderly. Consequently, the acute management of chronic oral-systemic conditions presented is below an acceptable standard of care (Elderton, 1990; Oral Health America, 2003; Asch et al., 2004; Tinnetti, 2004; Higashi et al., 2005; Reed et al., 2006). Postretirement/vulnerable populations also encounter environmental barriers that limit access to oral healthcare services with emergency room as the only viable option to access dental services (Martin et al., 2011).

Regardless of images and stereotypes of debilitation, frailty, and dependence, the majority (65%) of the elderly, are independent, healthy, active, and productive members of society (Flood, 2002; National Center for Health Statistics, 2006a,b; Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics, 2010; Older Americans, 2012). Advanced chronological age measures of the passage of time is not indicative of social, biological, or functional decline that increases the risk for disease and death (Gelberg, Andersen, & Leake, 2000; Crews, 2007). An individual sense of purpose in life, ability to effectively cope to cumulative physiologic and functional alterations associated with the passage of time while in harmony with spiritual connection results in successful aging (Flood, 2002; Roberts et al., 2006). Lifestyle practices are emphasized as a key risk factor of chronic disease progression, and positive lifestyle behaviors can reduce the stereotypical limitations of aging (Rowe & Kahn, 1997).

The goal of healthcare providers in treating the elderly is to improve function, maintain independence, and promote quality of life. The purpose of this chapter is to highlight the biopsychosocial challenges of the elderly in managing their oral healthcare needs and guide healthcare clinicians to integrate risk reduction and disease prevention in the health care of the elderly.

Biological, Physiological, and Systemic Determinants of Aging

The process of biologically normal aging affects the body systems at all levels. This process is described as a complex, malleable multidimensional process illustrated as a slow lifelong accumulation of cellular and molecular responses (wear/tear) to injury that produce low-grade chronic inflammation that may lead to organ/system decline, frailty, disease, and disability (Crews, 2007; Finch, 2007; Kirkwood, 2008). The process of aging occurs at different rates in different tissues dependent on environmental stressors, lifestyle habits, genetics, physiologic reserves, and biological resilience that influence health, severity of cellular and molecular damage that result in disease over the course of life (Partridge & Gems, 2002; Kirkwood & Austad, 2000). Acute levels of inflammatory proteins are beneficial early in life; physiologically negative effects on the body are neutralized by molecular, cellular, systemic, and individual mechanisms (adaption/remodeling capacity) that contribute to the survival, aging, and longevity of individuals (Barker, 1995). These markers of inflammation associated with aging have also been linked to oral health outcomes (Arola & Reprogel, 2005). The role of inflammation in aging is equally critical for healthy dental aging.

Data suggest that over the course of life, unfavorable early life events occur, such as DNA damage (intrauterine DNA methylation patterns, damaged DNA repair mechanisms), biopsychosocial and environmental stress-related events increase inflammatory load (causing disruption of homeostasis), increase cellular death rate, and deplete biological/physiological reserves that increase susceptibility to cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndromes, and postnatal infections (Iachine et al., 1998; Seeman et al., 2001; Boulet et al., 2006; Schoenmaker et al., 2006; Borghol et al., 2011; Kirkwood, 2011; Brant, Deindl, & Hank, 2012). These events play a pivotal role in the aging process.

Age-related subclinical structural/functional connective tissue (loss of elasticity, reduced keratin, and collagen) changes will accelerate blood vessels, airway passage, and organ rigidity with gradual decline in vital organ function (Seeman et al., 2001) Organ reserves also decline with advancing age primarily seen in heart, lungs, and kidneys. Daily psychosocial and environmental stressors will increase allostatic load combined with gradual decline in organ function that will lead to organ failure. Other synergistic effect of chronic stressors, toxins, and intrinsic cellular response mechanisms will contribute to tissue injury and trigger the onset of host repair mechanisms that lead to an increase in the collagen network deposits that develop in focal fibrotic scars, routinely noted clinically in blood vessels. In the brain, subclinical accumulation of plaques and tangles are observed as part of the normal aging process that will slow neurotransmission prior to expression of disease. Other age-related system changes include gradual decline in rate of metabolism clinically seen as increased and redistribution of body fat toward the abdominal area. Gradual decline in muscular tissue mass will compromise gait and balance.

Clinically elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure, waist to hip ratio (metabolism and adipose deposit), glucocorticoid activity (HDL), urinary cortisol, urinary epinephrine, and norepinephrine are measures of organ system changes that are a result of increase in allostatic load (Seeman et al., 2001). Allostatic measures related to physical function (ADL/IADL) have often been used to assess the individual’s ability to cope and adapt to daily task performance (Fried et al., 2005). Anger, anxiety, and depression, are psychological factors that increase allostatic load, promote stress-related disorders, compromise function, and promote disability.

Neuroendocrine Response

Synergistic age-related structural and functional (immunosenescence) changes in the immune system can occur in combination with chronic psychosocial environmental stressful (depression, irregular sleep patterns) events. In negative situations, immune system dysregulation will increase the risk of compromised wound healing, infection, neoplasm, autoimmune disease, and oral disease. Physiologically activated neuroendocrine response pathways modulate expansion of inflammatory toxins from reaching vital organs to cause loss of function (Hermann, Beck, & Sheridan, 1995). Physiologic characteristics of the normal aging process results in elevated levels of proinflammatory mediators (C-reactive protein [CRP], interleukin [IL]-6, and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]) that stimulate the neuroendocrine system and are associated with chronic disease (Franceschi et al., 2000; Ridker & Cook, 2004; Schaap et al., 2009). Chronic high levels of IL-6 are a potent predictor of human demise.

Psychosocial stresses/environmental toxins will trigger biochemical hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis by proinflammatory cytokines to increase cortisol secretion that is implicated in multiple chronic disorders ranging from psychiatric disease to somatic complaints (American Geriatrics Society, 2002; Kudielka, Hellhammer, & Wust, 2009). Age-related HPA decline will result in reduced hormone secretion and dysregulation of the immune response to stressful events (Seeman et al., 1994). Long-term individual psychosocial stressful events (caregiver for spouse with dementia, low socioeconomic status [SES]) will cause overload HPA and increase susceptibility to infectious diseases, contribute to immunosenescence, frailty, and disease. A blunted HPA response to chronic stress will promote autoimmune inflammatory disease.

Systemic Disease

Chronic levels of stress will weaken the blood–brain barrier, elevate sympathetic system stimulation, as well as increase circulating levels of cortisol. Chronic low level of inflammation has been identified as essential in initiation, progression, and disease complication (Libby, Ridker, & Maseri, 2002; Pai et al., 2004). Development of atherosclerosis is associated with increase in sympathetic system activity that includes increased insulin resistance and hemodynamic arterial wall changes that increase risk for cardiovascular events (Ross, 1999; Lu & Jin, 2010). Other changes include increased hyperglycemia, increased production of gastric acid secretion, inhibited excretion of sodium, accelerated potassium excretion, and a weakened immune system. Disease expression will vary by individual personality, emotion, and cultural, social environmental support systems. Anger, urbanization, and high job demands, have been shown to increase risk for hypertension and possibly impair ventricular function. Individual habitual intake of high-sodium diet and chronic levels of stress will increase cardiac output in early age expressed as hypertension and decreased cardiac output with advanced age due to peripheral vascular loss of elasticity, and left ventricular hypertrophy (Falk, Shah, & Fuster, 1995; Davi & Patrono, 2007).

Healthy aging is a universal aspiration that requires a healthy mind to maintain general autonomy, the ability to process information, and adaption to environmental changes. The most important aspect of aging that concerns the elderly is the ability to maintain a healthy mind (Vance & Crowe, 2006; Inelmen et al., 2007). However, mental health issues and cognitive limitations are more prevalent in the elderly population, most notably, an increased prevalence of dementia. The inability to perform ADL/IADL and maintain oral hygiene practices is a predictor of depression, cognitive decline, life dissatisfaction, loss of autonomy, and mortality (Chalmers & Pearson, 2005; Royall et al., 2005; McGuire, Ford, & Ajani, 2006; Meurman & Hamalainen, 2006; McGrath, Zhang, & Lo, 2009). One study reported that tooth loss prior to 35 years of age significantly increase risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (Gatz et al., 2006), while another study found elderly psychiatric adults have a higher prevalence of edentulism, poorer oral hygiene, and a higher score of dental caries experience (Lewis, Jagger, & Treasure, 2001). Other studies have shown a 2.6-fold increase in risk of Alzheimer’s when over half of natural tooth loss occurred prior to 50 years of age. In this study, the onset of periodontal disease was observed 20–30 years prior to expression of dementia (Stein et al., 2007). Elevated levels of apolipoprotein (APOE) ε 4 allele are more prevalent in edentulous elderly and are related to increased risk of dementia and vascular disease (Greenow, Pearce, & Ramji, 2005; Stein et al., 2007). Elders with dementia are more likely to have poorer oral hygiene practices and experience greater risk for oral disease (Kandelman et al., 2008).

Oral Diseases

Over 1 billion dynamic diverse microflora (balance pro-healthy and pro-disease bacterial species) contribute to the oral microbiome (microbial communities) that occupy the various oral cavity niches such as the dorsum of the tongue, buccal mucosa, teeth, periodontal tissues, soft palate, and tonsils contribute to maintain a healthy and balanced physiologic oral ecosystem (Zaura, Keijser, & Crielaard, 2009). Saliva is an essential element in the oral cavity to maintain homeostasis and defend against disease (Van Nieuw Amerongen, Bolscher, & Veerman, 2004; Krol & Grocholewicz, 2007). Biopsycosocial factors such as age, diet, smoking, alcohol, psychological stressors, pharmaceutical provocation, oral contraceptives, hormonal replacement therapy, compromised host defense, and systemic conditions will destabilize the environment, blunt the response by HPA axis to stress, alter the oral ecosystem, activate the parasitic virulent microbes, initiate disease, and impact quality of life (al’Absi et al., 2003; Gianoulakis, Dai, & Brown, 2003; Hilgert et al., 2006; Phillips et al., 2006; Kudielka & Wust, 2010; Badger, Ng, & Venter, 2011).

Chronic disease and physiologic changes increase the risk for oral diseases (Weber, 1974; Miller et al., 2001) and may result in decreased utilization of oral health care (Griffin et al., 2009). Furthermore, studies revealed that unmet dental needs were higher among elders with chronic diseases, resulting in pain and infection that reduce quality of life and affect normal daily activities.

Dental Caries

The majority of independent elderly are retaining their natural dentition with increased risk of coronal and root caries as well as tooth fractures of endodontically and nonendodontically treated teeth. Risk for dental coronal and root caries share the same etiology; however, the rate of disease expression is dependent on host biophysiological, sociobehavioral, and socioenviromental factors that result in disease expression and not always directly correlated with fermentable carbohydrate diet (Van Houte, 1994; Beltran-Aguilar et al., 2005; Brown & Dodds, 2008; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research [NIDCR]. National Institutes of Health, 2011) (Fig. 20.1). Environmental shift in oral ecosystem will shift healthy microflora to acidogenic (acid forming) and acidoduric (tolerate acidic habitat) associated with increased risk of dental caries and disease development in the elderly (Keyes, 1968). Majority of the elderly have high dental plaque scores, multiple restored tooth surfaces, high caries risk profile, fractured and premature tooth loss (Gilbert et al., 1996; Trovik, Klock, & Haugejorden, 2000; Curzon & Preston, 2004; Petersson et al., 2004; Eldarrat, High, & Kale, 2010). Cariogenic bacterial infection of the dental pulp often evolve into pulpal necrosis and periapical lesion, with activation of lipopolysaccharides and proinflammatory cytokines IL1-β and TNF-α, and initiate the inflammatory cascade that promotes bone resorption and contribute to systemic conditions (Tani-Ishii, Wang, & Stashenko, 1995; Meager, 1999). Normal aging process will increase the risk of gingival thinning and recession to create an environment for accumulation of bacterial plaque and development of caries that affect over 60% of the elderly (Lawrence et al., 1996; Hujoel et al., 2001; Steele et al., 2001; Borrell & Papapanou, 2005). The elderly are four times more likely to have unrestored dental caries than schoolchildren due to social-behavioral risk factors like smoking and financial access to care barriers that can result in pain, infection, reduced quality of life, and death (Dye et al., 2007). Topical and systemic exposure to fluoride and good oral hygiene practices will reduce risk for dental caries (Twetman, 2009).

Fig. 20.1. Factors involved in caries development. Adapted from Selwitz, Ismail, and Pitts (2007), with permission from Elsevier.

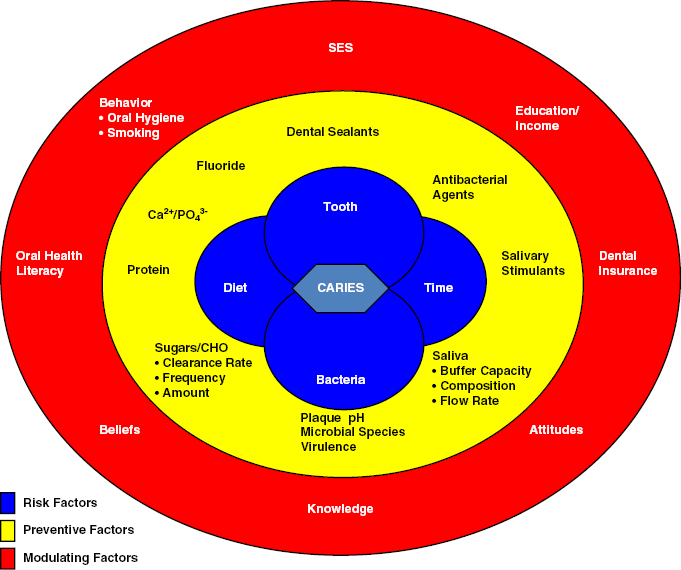

Periodontal Diseases

Diet accumulation of biofilm on the retentive surfaces of the natural dentition, lack of oral hygiene practices, and social habits elicit irreversible gingival inflammatory response that affect at least 17.2% of the elderly (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research [NIDCR]. National Institutes of Health, 2011). Gingivitis is multifactorial reversible periodontal disease prerequisite often undetected in early stages of disease with unpredictable host defense-dependent pathogenesis and understated prevalence (Scannapieco, 2004; Eke et al., 2010). Moderate forms of periodontal disease affect all populations (Demmer & Papapanou, 2010). Advanced stages of the disease affect 10–20% of the population. Prevalence varies with sociobehavioral factors, and compromised host and local and chronic systemic conditions have been identified as precursors of disease progression and tooth loss (Ship & Beck, 1996; Dye et al., 2007). The elderly are at higher risk of disease progression (Loe et al., 1986; Lockhart et al., 2008) (Fig. 20.2).

Fig. 20.2. Risk model for periodontal disease. Reprinted from Cappelli and Mobley (2008), with permission from Elsevier/Mosby.

Oral bacteria are able to penetrate blood vessels, connective tissue, and progress to invade tissues, organs, and systemic pathways that contribute to other systemic disease processes (Paju & Scannapieco, 2007; Kamer et al., 2008; Lockhart et al., 2012). Oral bacterial toxins have been traced to trigger systemic subclinical inflammation measured by elevated levels (CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α) of biomarkers in the elderly population (Bretz et al., 2005; Loos, 2005). Poorer glycemic control is particularly associated with elevated IL-1β cytokine levels found in gingival crevicular fluid that increase severity of gingivitis and periodontitis (Mealey & Rose, 2008; Somma et al., 2010). Elevated levels of IL-1β and TNF-α are correlated to severity of periodontal disease destruction and type 2 diabetes. Elevated levels of TNF-α may be associated with insulin resistance and obesity (Tilg & Moschen, 2008). Periodontal disease has been linked as a systemic risk factor to other systemic conditions such as hypertension, osteoporosis, and vitamin D deficiency (Offenbacher, 1996; Tonetti, 2009). Other studies have found that individuals with advanced periodontal disease that includes alveolar bone loss had increased risk of mortality (Garcia, Krall, & Vokonas, 1998). Patient-tailored oral hygiene instructions, as well as oral health destructive behavior modification and access to oral cleaning aids designed to meet the physical limitations of the elderly may promote disease prevention.

Edentulism

Edentulous rates have declined (26%) over the past decades as a result of oral health public education, water fluoridation, and sophisticated treatment modalities. Edentulism negatively influences oral function, facial appearance, speech, chewing efficiency, limits diet/nutritional intake, and psychosocial interaction (Gilbert et al., 2004; Griffin et al., 2012). Epidemiologic studies indicate edentulism is more prevalent among women with socioeconomic disparities; lack of dental insurance coverage, as well as inability to access oral care, and lower level of education affect quality of life, self-rated well-being, and self-esteem. Artificial prostheses will impair chewing efficiency by 30–40% in comparison with natural teeth, as well as impair the swallowing threshold requiring seven times more chewing strokes to mill the bolus of food prior to swallowing; therefore, food selection is compromised and is less enjoyable (Idowu, Handelman, & Graser, 1987). Impaired chewing efficiency results in consumption of low fiber, high saturated fat, less carotene, fewer fruits/vegetables, and is demonstrated to increase levels CRP, IL-6, and fibrinogen that increase the risk of coronary heart disease. Other studies have demonstrated that dietary selection is influenced more by race, culture, and SES, and is less dependent on the number of functional occlusal contacts (Gotfredsen & Walls, 2007). Edentulism contributes to a number of systemic and psychosocial conditions such as increased incidence of denture stomatitis, aspiration pneumonia, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, sleep disorders, gastric lining mucosal infections, with social isolation, decreased self-esteem, and physical inactivity.

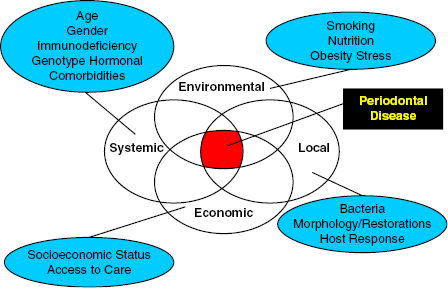

Oral Cancer

Oral cancer primarily involves the tongue, floor of the mouth, and lips, whereas oropharyngeal cancer expands to involve the posterior third of the tongue, soft palate tonsilar area, and posterior and lateral walls of the throat which accounts for 3% of all cancers and is rated as the eighth most common cancer challenging Americans (Shiboski, Shiboski, & Silverman, 2000). Pathogenesis of the disease is associated with social-behavioral habits such as use of tobacco and alcohol products, unprotected exposure to ultraviolet radiation, and inadequate consumption of grains, fruits, and vegetables (Fig. 20.3). Use of tobacco products accounts for 75% of oral cancer deaths, whereas use of alcohol is the second risk factor associated with nutritional deficiency. Other risk factors that account for 20–25% of oropharyngeal cancer is human papillomavirus (HPV), especially HPV-16 detected in the posterior third of tongue, tonsilar area, and oropharynx (Falkry & Gillison, 2006; D’Souza et al., 2007). Incidence of oropharyngeal cancer related to HPV increased annually (4.4%) during 1999–2008 among those 15–64 years of age, whereas cancer in other sites of the oral cavity have declined or remained the same (American Cancer Society, 2012). Individuals who are seropositive for HPV-16 have a 15-fold increased risk of expressing oropharyngeal cancer. Oropharyngeal cancer estimates for 2012 are 40,250 new cases, with 7850 deaths and 50% survival rate (American Cancer Society, 2012). One study suggests that every hour, one American dies from oral cancer (Kademani, 2007).

Fig. 20.3. Risk model for oral cancer. Oral cancer is a multifactorial disease process that includes systemic, environmental, and economic effects. The interplay of these variables ultimately lead to the incidence of this disease. The multifactorial nature of oral cancer should be addressed in the assessment of a patient’s risk. Reprinted from Cappelli and Mobley (2008), with permission from Elsevier/Mosby.

Since oral diseases are largely behavioral in origin, oral health promotion activities aimed at the elderly are fundamental to any disease prevention strategy. Health promotion is the process that enables individuals to increase control over and improve their oral health through education and prevention (World Health Organization, 1986). By developing a sound plan of prevention, the dental professional can provide the elderly with the tools to prevent their risk for future disease.

Environmental and Psychosocial Factors of Aging

Environmental Determinants

Multilevel interactive influences of individual (attitude, skills), social (formal/informal social network, family, peer group, workplace, and organization), and socioeconomic environmental (culture, media, resources, local, state, national) factors shape behaviors expressed by an individual and population that significantly contribute to each category of disease progression (Sallis et al., 2006; Glanz & Bishop, 2010). Socioeconomic environmental inequalities cause disparities in health and promote the practice of health-compromising behaviors. Social factors play a key role in the oral health of the elderly. In the United States, employer-based dental insurance ceases upon retirement (Manski et al., 2009). Routine dental care is not offered under current Medicare guideline, whereas dental care Medicaid resources are being reduced. In addition, only a small percentage of Medicare supplemental programs offer dental benefits (Manski et al., 2011). Regular dental care becomes an out-of-pocket cost for most of the elderly and creates a profound barrier to care. Lack of geriatric-trained dental providers also contributes to barriers to care that have been characterized as a U.S. health crisis (Oral Health America, 2003). The elderly with private dental insurance are 50% more likely to visit a dentist than those without dental benefits (Brown, Goryakin, & Finlayson, 2009).

Most elderly live in urban settings, while 1.57 million reside in total care facilities; over 1 million occupy assisted-living facilities, and access to oral healthcare services is a daily challenge. Federal, state, and other regulatory agencies require that oral care services be offered to institutionalized residents; however, in a recent report, only 13% of the residents received dental care (Berkey et al., 1991; Jones, 2002; MacEntee, Pruksapong, & Wyatt, 2005; Reed et al., 2006; Dounis et al., 2012). Evidence-based governmental policy intervention to reduce health inequalities and disparities are required to shape healthy society and aging in place communities (Graham, 2004).

Social

Social communities, networks, the quality, and quantity of relationships are important predictors of cognitive function, physical/functional health, autonomy, and self-assessment of lifestyle satisfaction. Together these things portray the complexity of healthy aging. Healthy choices are initially rooted in the socioeconomic circumstance rather than an individual behavior (Evans & Stoddart, 1990; Ewart, 1991). Social norms, values, and beliefs are shaped by the societal view of the individual, and the value the individual brings to society influences behavior. Level of education, gender, younger lifestyle practices, and rural/urban residence are important predictors of mortality. Each of these factors influences the behaviors an adult adopts or discards as they progress across a life span. The decision to seek healthcare services by the elderly is dependent upon perceptions, values, family/social network, social norms, attitudes, and cultural beliefs, as well as the elderly’s past experiences or witnessed events during a medical/dental encounter. Youth-oriented societies create stigmas, negative images of older adults that translate to individuals internalizing a negative self-image that result in possible underreported symptoms of a disease (Horton et al., 2008). A growing body of evidence suggests that healthcare professionals perceive medical conditions presented by older adults as irreversible, unprofitable, and unexciting (Gunderson et al., 2005; Kane & Kane, 2005; Jopling, 2007).

Limitations with ADL reduce the opportunity for the elderly to seek routine dental care. Many dental practices are not equipped to provide care for the nonambulatory patient or patients with other significant limitations. While dental professionals treat all patients with dignity, they lack the knowledge and skills to manage the functional limitations (e.g., walking, getting in and out of dental chairs, bathing, dressing, eating) and social deficits of the elderly. Women with functional limitations endure more barriers to access to dental services than men. One study found that women with two or more limitations in ADL were 40% less likely to access dental services when compared to women with fewer limitations (Manski et al., 2011). The elderly face additional barriers to accessing routine dental care. As we age, vision and hearing deficits are more prevalent, and therefore, transportation services are needed for the community-dwelling elderly who is living alone and to whom this may be another form of isolation.

Recent studies have reported the emergence of a new generation of elders who are actively engaged in social networks and community interests and have a quest for learning positive outlook on living despite chronic ailments (Ferrario et al., 2008). The degree of esteem accorded to the elderly is strongly correlated with the perceptions of usefulness in their families and communities (Harris & Thoresen, 2005; Gokalp et al., 2007).

Majority of the elderly will age in place in communities where they lived, grew older with their peers, and transformed communities into naturally occurring retirement communities (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics, 2010). A small percentage (4–5%) of older adults will participate in interstate permanent long-distance migration. Seasonal migration of elderly to regions with favorable climate, housing, and favorable tax structures favors short-term economic prosperity but transfers the burden for health care to distant rather than lifelong local communities. Nearly 1 billion people travel the world annually, with the elderly representing one-third of the passengers (World Tourism Organization. UNWTO, n.d.). An interoperable electronic health record must be available to interprofessional healthcare providers at the local, state, national, and international healthcare facilities to effectively manage chronic oral-systemic conditions presented by the elderly as they become more mobile.

Individual

Self-rated health status is a multidimensional, dynamic, objective measure of functional and psychosocial well-being and a more accurate representation of the elderly’s health status (Lundberg & Manderbacka, 1996). An individual’s self-perception is a reflection on decline/improvement of health, which is influenced by individual lifestyle behavioral habits, SES, and environmental factors, and have been correlates as a more objective assessment of successful aging (Shooshtari, Menec, & Tate, 2007). Domains most significantly associated with self-rated healthy aging and well-being were independent functioning, physical condition, personal control/autonomy, and responsibility (McMullen & Luborsky, 2006). Most adult social habits are adopted during early adolescence. These instilled habits contribute to morbidity and mortality later in life. Effective early intervention programs to promote healthy lifelong behaviors and habits can prevent health-compromising behavioral practices (Dobbins et al., 2009). Negative self-perception of health has been linked to increased complexity of chronic conditions and hospital admissions. Optimistic attitudes and behaviors will accelerate surgical recovery, promote ability to repair damaged tissue, and promote resistance to disease and illness.

Race Gender

Fifty percent of the elderly population is projected to be more racially and ethnically diverse by 2100. The elderly of Hispanic origin will represent the largest (20%) racial/ethnic minority by 2050 followed by the elderly of Asian origin. Racial and ethnic diversity will affect variability in living arrangements, life expectancy, social economic status, and level of education. The elderly with high school diplomas and bachelors degree have increased in number over the years; however, African Americans and Hispanics have the lowest educational achievement and have substantially lower income. Higher level of education is associated with more positive self-perceived health and use of healthcare services among the elderly (Idler, 1993). Increasing economic disparities and earning distribution have health and well-being implications. There is conflicting evidence on compliance and use of healthcare services among elderly men and women (Hulka & Wheat, 1985; Verbrugge & Wingard, 1987). However, the women have longer life span, are diagnosed with conditions that are more chronic, and are more likely to use healthcare services (Murphy & Hepworth, 1996).

Cultural Aspect of Health

Culture has been referred to as a complex dynamic, continuous, coping mechanism, learned way of life shaped by people that share similar beliefs, values, customs, and norms, passed down from generation to generation that may unite or divide people. Multiple socialization experiences instill culture in individuals and become a powerful filter through which information is received and processed that effect utilization of healthcare services, health outcomes, and well-being from birth until death. Health-related behaviors, beliefs, values, attitudes, practices, use of therapeutic services, and health services outcomes are related and shaped by culture that can serve as a therapeutic barrier or resource for the individual as well as the cultural community (Haas et al., 2004). Core cultural beliefs of immigrants remain unchanged even after assimilation into western culture. Transformative power of information technology and penetration of media across cultural boundaries may lead to greater infusion of ideas influencing values, norms, identities, and construct of assumptions. Research has found that individuals are more likely to accept health-related recommendations from people they like, respect, and with those they share common traditions and beliefs (Anderson, 1987).

Approximately 90 million adults lack the literacy skills to improve their overall well-being; less than 50% of the elderly access the Internet, whereas 50 million encounter barriers and are unable to access Internet health-related content (Lenhart, 2000). Literacy goes beyond reading, writing, and communicating is the elderly’s ability to understand and remember recommendations made by clinicians and obtain needed services to self-manage their oral-systemic chronic conditions (Office of Minority Health [OMH], 2001). Some of the elderly have literacy skills below high school level. They are poor, minority populations, and groups with limited English proficiency, such as recent immigrants. Studies have found that the elderly with limited oral-systemic health literacy have limited knowledge and understanding about their chronic diseases and are less likely to use health-preventative services and are most likely to report adverse outcomes (DeWalt et al., 2004, 2006, 2010; Dye et al., 2007). Recent studies assert that nondental healthcare professionals have insufficient training and lack knowledge of oral-systemic impact on health and do not examine the oral cavity during routine physical examination (Quijano et al., 2010; ACGME, 2012). Others have concluded that health information brochures are full of jargon and obscure words, and are not directed to the target audience, resulting in communication gaps and undesirable health behaviors (Rudd, 2007). Multicultural communication skills are required to ensure healthcare professionals effectively communicate with patients of all ages and cultures (Xakellis et al., 2004; Cannick et al., 2007). Briefly, it has been recommended that clinicians adopt (1) welcoming attitude, (2) maintain eye contact, (3) use plain nonmedical language with use of graphics, (4) slow down, (5) break information into short statements, (6) focus on few key concepts, (7) check understanding using teach-back, and (8) encourage patient/family participation (DeWalt et al., 2010).

Western medical philosophy and management of illness is scientifically based; illness and disease are measured and observed where the mind, body, and spirit are separated. This approach may be in direct opposition to certain cultural health beliefs and may create an environment of misunderstanding, mistrust, nonadherence, misdiagnosis, and adverse health events. Eastern cultures’ approach to healing is holistic: the mind, body, and spirit are essential to health and illness referred to as alternative medical system. Asians, Pacific Islanders, Native Americans, and Hispanics have adopted traditional alternative medical models of care (Salimbene, 1999; Lai & Surood, 2009).

Common Behavioral Oral-Systemic Disease Risk Factors

Diet and nutritional consumption have been associated to contribute to a number of oral-systemic conditions. Consumption of high saturated fats and carbohydrates, and low intake of fiber, fruits, and vegetables, as well as sedentary lifestyle practices, are associated with elevated CRP, IL-6, and increased risk of chronic oral-systemic conditions.

Smoking has been identified as a psychosocial risk factor for oral-systemic disease that is related to periodontal disease and poor oral health/hygiene, and contributes to the development of 30% of all cancer and associated comorbidities and 90% of lung cancer. Exposure to cigarette smoke will initiate inflammatory response of tissues and organ systems, primarily affecting the airway and leading to injury, remodeling, and chronic inflammation.

Stress/Control has been related to individual and environmental factors. Lack of control, low socioeconomic factors, caregiving, and health inequality have been recognized as psychosocial factors that compromise oral-systemic conditions. Elevated levels of salivary cortisol have been linked to extent and severity of periodontal disease and temporomandibular joint dysfunction that may exacerbate chronic systemic conditions, frailty, and demise.

Alcohol is a psychosocial behavior habit initiated during years of adolescence with short-term enhanced mood influenced by social and environmental factors that affect chronic oral-systemic conditions. Consumption has been associated with traumatic injuries; chronic use will lead to neurological, cognitive impairment and increased risk of suicide.

Hygiene in general is necessary to reduce inflammatory toxins and improve oral and systemic health. Effective removal of the oral microbiome has been associated with good oral health and reducing risk of chronic inflammatory systemic conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, aspiration pneumonia, and infectious diseases.

Physical inactivity has been shown to increase the risk of multiple chronic systemic conditions, such as falls, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, frailty, and osteoporosis, and Alzheimer’s as well as increased inflammatory markers compromise the immune system that will impact oral disease (Sheiham, 2000; Sheiham & Watt, 2000).

Oral-Systemic Risk Assessment and Intervention Strategies

Oral healthcare practitioners have the opportunity as part of the primary healthcare team to assess the physical, behavioral, and social risk factors that contribute to the pathophysiology of chronic oral-systemic conditions. Social (low SES, culture, chronic stress, depression, social isolation) and behavioral (tobacco, alcohol, stress, diet, physical inactivity, hygiene) risk factors contribute to pathophysiologic breakdown of tissues and organs that result in disease progression. Self-assessed health (the will to live) is a powerful predictor of mortality that measures how the elderly perceives their own health. The simple question of “How is your general health” has resulted in the responses that will go beyond the physical aspects to extend to attitude/perceptions and socioeconomic barriers that contribute to their physical status. Table 20.2 provides a framework of open-ended self-rated questions on the determinants of health. The elderly often use their physical and functional health status as a reference in rating their own health and compare it to others in their own age group as well as other age groups. There are several objective measures to assess health; however, self-rated health has been a predictor of self-esteem, social support, and a predictor of future self-rated health (Simon et al., 2005; Shooshtari, Menec, & Tate, 2007).

Table 20.2 Self-Rated Oral-Systemic Risk Assessment for Older Adults with Chronic Conditions

| Determinants | Risk-assessment questions |

|---|---|

| Oral-syst/> |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses