CHAPTER 2 THE SURGEON GENERAL’S REPORT ON ORAL HEALTH IN AMERICA: DEFINING CHALLENGES FOR THE FUTURE

In April 1997 Donna Shalala, then Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, commissioned the Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health in America (Surgeon General’s Report). The Secretary charged the report to “define, describe and evaluate the interactions between oral health and general health and well-being (quality of life), through the life span, in the context of changes in society.”1 During the next 3 years, under the direction of the Office of the Surgeon General and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Project Director Caswell A. Evans, D.D.S., M.P.H., coordinated the efforts of a highly qualified project team and a cadre of contributing authors and content experts. By early 2000 the project team’s dedication and determination paid off, and the first-ever Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health was completed.

This chapter intends to fulfill a number of objectives. It provides a brief history of the U.S. Public Health Service, presents a chronology of Surgeons General throughout time, and places the current Surgeon General’s Report in the context of previous reports. The chapter also summarizes the Surgeon General’s Report and its important messages to the American public. Although the chapter provides a thorough synopsis, it does not intend to provide a critical review of the Surgeon General’s Report. The breadth of such a critical review would be well beyond the scope of this chapter. Finally, the chapter places the Surgeon General’s Report in the broader context of selected oral health initiatives at the national, state, and local levels.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE U.S. PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE

During our nation’s early history, port cities found themselves poorly equipped to handle the health care needs of merchant sailors. On July 16, 1798, in an attempt to remedy the situation, President John Adams signed An Act for the Relief of Sick and Disabled Seamen, providing for “the temporary relief and maintenance of sick or disabled seamen in the hospitals or other proper institutions now established in the several ports of the United States, or in ports where no such institutions exist, then in such other manner as he (the Secretary of the Treasury) shall direct” (1 Stat. L. 605).2 The Act called for a tax of 20 cents per month against the wages of all American sailors. Funds were to be used to provide health care to merchant seaman in existing marine hospitals or to construct new hospitals, where necessary. The Act gave the authority for local collection and administration of a Marine Hospital Fund. In 1799 a new law granted that naval personnel would also be beneficiaries of the Marine Hospital Fund, a provision that lasted until 1811, when the U.S. Navy created its own hospital system.3

Local administration of the service left administration of the hospitals subject to the whims of politicians and customs collectors. During the next several decades, the Marine Hospital Fund health care system devolved into a disjointed, poorly functioning organization of hospitals.4 In 1849 the Marine Hospital Fund appointed Drs. George Loring and Thomas Edwards to lead a commission charged with evaluating the Fund hospitals. Their report placed the Fund hospitals and their local administrators in a less than favorable light. Loring and Edwards were also the first to recommend a “chief surgeon” to provide central leadership to the Fund system. During the Civil War, the Marine Hospital Fund fell into further disarray, as some hospitals were overrun by soldiers, and others were abandoned completely. In 1869 the Treasury Secretary, then administrator of the Fund, commissioned Drs. Stewart and Billings to inspect and report on the hospitals. Again, the hospital system was found to be in dismal shape.

During the following year, in response to the unfavorable report, the Secretary initiated some organizational changes.4 In 1871 Dr. John Maynard Woodworth, General Sherman’s chief medical officer during the Civil War, became the first Supervising Surgeon of the Marine Hospital Service (a position later to be renamed Supervising Surgeon General and then simply Surgeon General). Woodworth brought his experiences with disciplined military service to the position and set in motion a series of reforms that would shape the Marine Hospital Service to come. Dr. John B. Hamilton, successor to Woodworth, wanted to make Woodworth’s reforms permanent, and his campaign to do so was successful when, on January 4, 1889, President Cleveland signed an Act to Regulate Appointments in the Marine Hospital Service of the United States (25 Stat. L. 639). The Act specified that the medical officers would thereafter be appointed by the president, with the advice and consent of the Senate, after passing an examination. These reforms have remained in the Marine Hospital Service to the present.

Over the next three decades, the Surgeons General orchestrated a broader scope for the Marine Hospital Service, which also resulted in two changes in name.5 During the tenure of Surgeon General Wyman, for example, the budget for the Marine Hospital Service nearly tripled and the number of staff physicians more than doubled. In 1902, in an effort to reflect the new responsibilities of Marine Hospital Service physicians in combating infectious disease, Wyman guided the Congress to change the name of the Marine Hospital Service to the Public Health and Marine Hospital Service and had the term Supervising eliminated from the Surgeon General title.

Between 1912 and 1920 the Public Health and Marine Hospital Service gained greater notoriety and responsibility.6 During the tenure of Surgeon General Rupert Blue, Congress passed legislation that changed the name of the Public Health and Marine Hospital Service to the Public Health Service. The charge of the newly named Service was to investigate diseases and conditions that resulted from sanitation, sewage, and pollution of U.S. streams and lakes. During Blue’s period, as a result of demands for health care personnel during World War I, the Public Health Service allowed the commissioning of reserve officers, including pharmacists, sanitary engineers, and dentists.

Changes in the Public Health Service took place at a dramatic rate after World War I. Between 1920 and 1936 the Public Health Service introduced the new fields of epidemiology and biostatistics to various public health problems throughout the country.7 In 1939 President Roosevelt combined the Public Health Service with a number of other educational, health, and welfare offices into the Federal Security Agency.8 In 1942 the Public Health Service launched a campaign against malaria in military training camps called Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA); in 1946 the MCWA program became a permanent agency of the Public Health Service and was renamed the Communicable Disease Center, which later became the Centers for Disease Control, and, finally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In 1948 Congress added the National Institutes of Dental Research (NIDR) to the National Institutes of Health, and H. Trendley Dean was named the first director of the new dental institute.9 In 1953 additional agencies, hospitals, and the Office of Vital Statistics were combined with the Federal Security Agency to create the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). In 1955 the Public Health Service took over the medical care of American Indians from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.10

During the 1970s, prompted by a sweeping reorganization of HEW by Secretary Gardner (1965-1968), the Public Health Service evolved from a three-agency structure into a six-agency structure.11 In 1972 the Public Health Service consisted of the newly arrived Federal Drug Administration (FDA), National Institutes of Health, and Health Services and Mental Health Administration (HSMHA). The HSMHA consisted of the Indian Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, Regional Medical Program, Public Health Service hospitals and health planning programs, and other agencies. In 1973 the six agencies included the CDC; Health Services Administration (HSA); Health Resources Administration (HRA); Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (ADAMHA); and a combination of the FDA, National Institutes of Health, and four new agencies created by HSMHA.

SURGEONS GENERAL OF THE U.S. PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE: A CHRONOLOGY

Including Surgeon General Satcher, 16 persons have occupied the Office of Surgeon General since John Woodworth assumed the position in 1871 (Box 2-1). Most of the Surgeons General have been men. The first woman to assume the position was Surgeon General Novello, who served from 1990 through 1993. Dr. Novello was also the first Hispanic Surgeon General. In 1993 M. Joycelyn Elders became the second woman and the first African-American to assume the position. Surgeon General Satcher, who was appointed by the Clinton administration in 1998, became the first African-American man to hold the office.

| John M. Woodworth | 1871–1879 (died) |

| John B. Hamilton | 1879–1891 |

| Walter Wyman | 1891–1911 (died) |

| Rupert Blue | 1912–1920 |

| Hugh S. Cumming | 1920–1936 |

| Thomas Parran, Jr. | 1936–1948 |

| Leonard A. Scheele | 1948–1956 |

| Leroy E. Burney | 1956–1961 |

| Luther L. Terry | 1961–1965 |

| William H. Stewart | 1965–1969 |

| Jesse L. Steinfeld | 1969–1973 |

| S. Paul Ehrlich (acting) | 1973–1977 |

| Julius B. Richmond | 1977–1981 |

| C. Everett Koop | 1981–1989 |

| Antonia C. Novello | 1990–1993 |

| M. Joycelyn Elders | 1993–1994 |

| Audrey Manley (acting) | 1995–1997 |

| J. Jarrett Clinton (acting) | 1997–1998 |

| David Satcher | 1998–2002 |

| Kenneth Moritsugu (acting) | 2002– |

From 1871 until the present, the Surgeons General have taken on a variety of responsibilities and have assumed various roles. Before 1968, for example, the Office of the Surgeon General assumed full responsibility for leading the Marine Hospital Service (and later the Public Health Service), including program development, administration, and financial management. In the position as head of the Marine Hospital Service or Public Health Service, the Surgeon General reported directly to the president or his Cabinet. In 1968 President Johnson reorganized the federal government and took management of the Public Health Service away from the Office of the Surgeon General and placed it in the hands of the Assistant Secretary for Health (ASH). With this reorganization, the Surgeon General was to become a principal deputy to the ASH, losing administrative responsibilities and, instead, offering advice regarding professional medical issues.

REPORTS OF THE SURGEONS GENERAL THROUGHOUT HISTORY

Beginning in the mid-1960s the Surgeon General of the U.S. Public Health Service had endeavored to educate the nation about important public health problems by releasing reports on a regular basis. To date, the Office of the Surgeon General has released more than 50 such reports. The vast majority of them have dealt with cigarette smoking and other tobacco-related health issues (Box 2-2); however, beginning in the 1980s, other reports have introduced such diverse topics as disabilities among children, acquired immune deficiency, nutrition and health, child abuse, physical activity, suicide, youth violence, mental health, responsible sexual behavior, and oral health. From the beginning, the reports of the Surgeons General have had a tremendous influence on health and health-related behaviors in the United States.

BOX 2-2 Reports of the Surgeon General of the U.S. Public Health Service

| 2001 | Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behavior |

| National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action | |

| Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General | |

| Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General | |

| 2000 | Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General | |

| 1999 | Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Suicide | |

| 1998 | Tobacco Use among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| 1996 | Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| 1994 | Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| Surgeon General’s Report for Kids about Smoking | |

| 1992 | Surgeon General’s Report to the American Public on HIV Infection and AIDS |

| Smoking and Health in the Americas: A Report of the Surgeon General | |

| 1990 | The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| 1989 | Reducing the Health Consequences of Smoking—25 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| 1988 | The Surgeon General’s Letter on Child Sexual Abuse |

| The Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health | |

| The Health Consequences of Smoking—Nicotine Addiction: A Report of the Surgeon General | |

| 1987 | The Surgeon General’s Report on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| 1986 | Smoking and Health. A National Status Report: A Report to Congress |

| The Health Consequences of Involuntary Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General | |

| The Health Consequences of Using Smokeless Tobacco | |

| 1985 | The Health Consequences of Smoking—Cancer and Chronic Lung Disease in the Workplace: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| 1984 | The Health Consequences of Smoking—Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease | |

| 1983 | The Health Consequences of Smoking—Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| 1982 | Report of the Surgeon General’s Workshop on Children with Handicaps and Their Families |

| The Health Consequences of Smoking—Cancer: A Report of the Surgeon General | |

| 1981 | The Health Consequences of Smoking—The Changing Cigarette: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| 1980 | The Health Consequences of Smoking for Women: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| 1979 | Healthy People—The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention |

| Smoking and Health | |

| 1977–78 | The Health Consequences of Smoking |

| 1976 | The Health Consequences of Smoking: Selected Chapters from 1971 through 1975 Reports |

| 1975 | The Health Consequences of Smoking |

| 1974 | The Health Consequences of Smoking, 1974 |

| 1973 | The Health Consequences of Smoking, 1973 |

| 1972 | The Health Consequences of Smoking |

| 1971 | The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General |

| 1969 | The Health Consequences of Smoking: 1969 Supplement to the 1967 Public Health Service Review |

| 1968 | The Health Consequences of Smoking: 1968 Supplement to the 1967 Public Health Service Review |

| 1967 | The Health Consequences of Smoking. A Public Health Service Review |

| 1964 | Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee of the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service |

The first report (Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee of the Surgeon General of the U.S. Public Health Service), released in 1964 during Surgeon General Terry’s tenure, introduced the causal relation between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. The report took the nation by storm. In January 1964, before a standing-room-only press conference, the Surgeon General announced the findings of his Advisory Committee on Smoking and Health. During the conference, Terry stated that “cigarette smoking is causally related to smoking in men,” and added, “the magnitude of the effect of cigarette smoking far outweighs all other factors. The data for women, though less extensive, point in the same direction.”12 As a result of this report, the Federal Trade Commission immediately called for warning labels on cigarette packaging and Congress passed legislation requiring their use. The influence of the first Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health was far reaching. The report not only effected a dramatic change in the way that the average citizen viewed smoking, but it established prestige for the reports that would follow and secured a special place for the Surgeon General in the public’s eye.

In 1979 Surgeon General Richmond released Healthy People—The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention.13 The document was important because it defined, for the first time, national health objectives against which progress during the following decade could be measured. This chapter discusses the oral health priority area for these “Healthy People 1990” objectives, as well as the “Healthy People 2000” and “Healthy People 2010” objectives, in a later section.

One of the most influential reports written during the 1980s was The Surgeon General’s Report on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, released by Surgeon General Koop.14 This document, much of which was written by Koop himself, described sex education in elementary schools, addressed the proper use of condoms and other prophylactics, and called for tolerance of those infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although the report used explicit language and, to many, was controversial, it was also immensely popular among public health professionals and the public. The Surgeon General’s report on HIV, as well as the document that followed (Understanding AIDS), brought useful, accurate, and nonjudgmental information to a nation that was frightened of a serious public health problem of which they knew little.15

On May 25, 2000, at Shepherd Elementary School in Washington, D.C., Assistant Secretary for Health and Surgeon General David Satcher released Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General.16 The document was the first-ever Surgeon General’s report exclusively dedicated to oral health issues and was the fifty-first in a series of Surgeon General’s reports since 1964. In his presentation to the American public that day, Surgeon General Satcher summarized key themes of the report and placed the findings in a broader context of general health and well-being. Dr. Satcher stated that oral health meant much more than healthy teeth; that oral health was integral to general health; that safe and effective disease prevention measures existed that everyone could adopt to improve oral health and prevent disease; that profound disparities in oral health existed in the United States; and that general health risk factors, such as tobacco use and poor dietary practices, also affected oral and craniofacial health.

SUMMARY OF THE SURGEON GENERAL’S REPORT ON ORAL HEALTH

The Surgeon General’s Report was a comprehensive document, with more than 300 pages of text, tables, figures, illustrations, and references. This section summarizes the landmark report’s organization, major findings, and framework for action. To be faithful to the Surgeon General’s Report, this section borrows liberally from the original document. Interested persons are encouraged to read the Surgeon General’s Report in its entirety if they wish to have access to greater detail.16

Organization of the Report

The project team and contributing authors divided the Surgeon General’s Report into five parts, each part relating to a particular question. Part One asked, What is oral health? This central question was addressed across two chapters. The first of these chapters affirmed that oral health meant more than healthy teeth, a theme that would recur throughout the report. The chapter stated that oral health meant being free of diseases and conditions that affect the full complement of oral, dental, and craniofacial tissues, collectively known as the craniofacial complex. This distinction is important because the function of the craniofacial tissues is often taken for granted, despite providing for such uniquely human traits as speech and facial expression. The first chapter also followed the lead of the World Health Organization by stating that oral health simultaneously included physical, mental, and social well-being, and this connection between oral health and general health represented a second theme of the report.17 In spite of the authors’ desire to define oral health in broad terms, however, the chapter also stressed the importance of two leading tooth-related problems, dental caries and the periodontal diseases. The second chapter of Part One provided an overview of the craniofacial complex during development. Together, the two chapters of Part One provided the background against which the remainder of the Surgeon General’s Report could be more fully appreciated and understood.

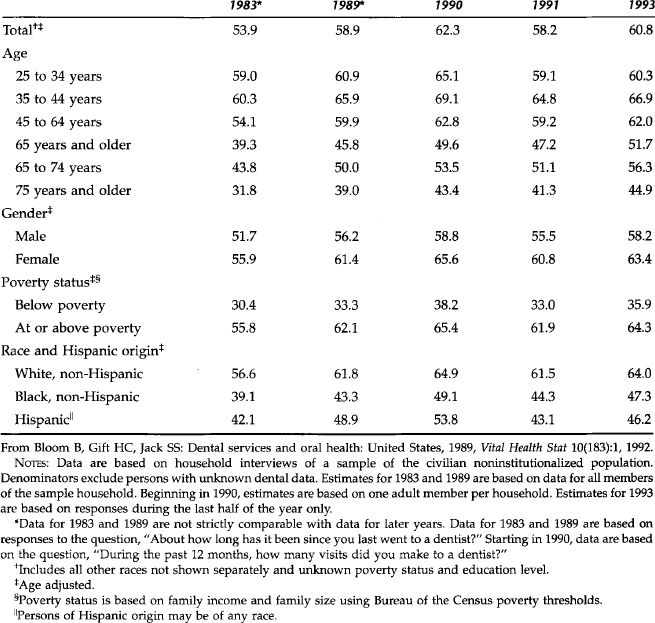

The second chapter of Part Two described the distribution of the oral diseases and conditions listed in the first chapter. The authors derived most of their descriptive statistics from large surveys representative of the civilian, noninstitutionalized U.S. population. These data sources included the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), surveys conducted by the National Institute of Dental Research (currently the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research) during the 1970s and 1980s, and others.18–25 The second chapter stated, however, that “there is no single measure of oral health or the burden of oral diseases and conditions, just as there is no single measure of overall health or overall disease” (Surgeon General’s Report, p. 61).16 The chapter reached the following conclusions:

Part Three of the Surgeon General’s Report asked, What is the relation between oral health and general health and well-being? This question was addressed across two chapters. The first chapter characterized the face and oral cavity as a reflection of health and disease in the body and described numerous established and potential linkages between oral health and general health. It also showed how diagnostic tests of saliva were available to detect antibodies, drugs, hormones, and environmental toxins, as well as to determine the integrity of the mucosal immune system.26,27 The first chapter reached the following conclusions:

The second chapter of Part Three focused on the relation between oral health problems and quality of life. The authors set the stage for this relation with a description of the role that oral health value systems have played in society and across cultures. The authors went on to describe the effect that poor oral health had on the functions of daily living, such as communication, social interaction, and intimacy.28 The chapter reached the following conclusions:

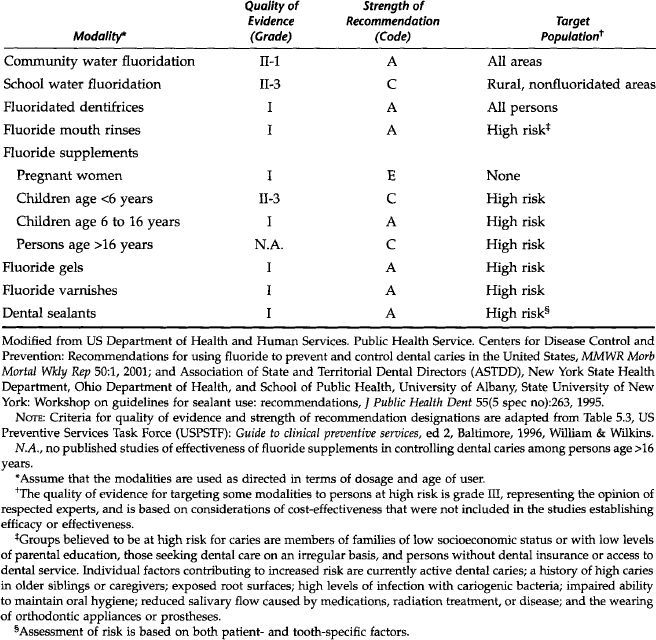

Part Four asked, How is oral health promoted and maintained, and how are oral diseases prevented? These related questions were addressed across three chapters. The first chapter reviewed the evidence regarding current prevention measures, with particular emphasis on the prevention of dental caries (Table 2-1). In addition, the chapter acknowledged a need for the prevention of periodontal diseases, facial injuries, and oral and pharyngeal cancer; however, the authors suggested that current preventive measures were at an early stage. The authors also stated that studies regarding the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of health practitioners and the public showed numerous educational opportunities. The chapter reached the following conclusions:

Table 2-1 Quality of Evidence, Strength of Recommendation, and Target Population of Recommendation for Each Modality to Prevent and Control Dental Caries

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses