Chapter 2

Development of Periodontal Diseases in the Younger Population

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to outline the defects in biological processes that may lead to the development of periodontal diseases in the younger population.

Outcome

After reading this chapter the practitioner should be able to appreciate that the balance between host defence mechanisms and microbial plaque influences periodontal disease outcome. The nature of plaque and what constitutes the host defence against microbial plaque should be clear. Susceptibility to disease is dependent on the interplay between a number of risk factors. The practitioner should be aware of these at all levels: the patient, the mouth, the individual tooth and the specific site. Finally, the transition from established gingivitis to periodontitis in the young patient should be understood.

Balance: Microbial Challenge Versus Host Defence

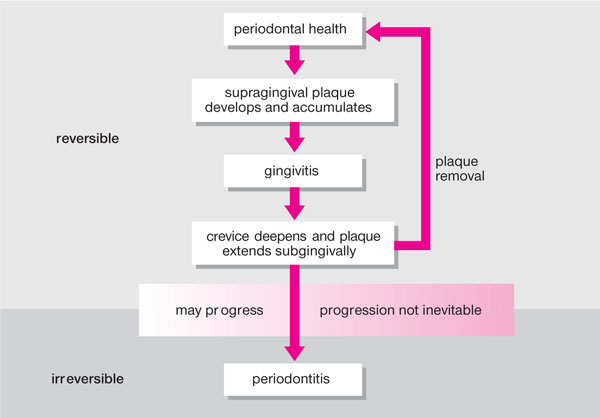

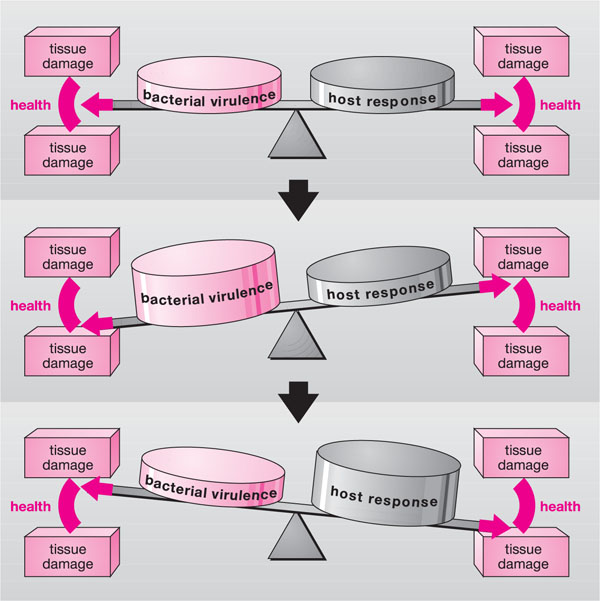

Whilst the microbial aetiology of gingivitis is not in any doubt, the transition from reversible plaque-induced gingivitis to irreversible periodontitis is unpredictable (Fig 2-1). In a balanced situation, the host’s defence mechanisms can contain the pathogenic effects of the microbial plaque so that disease does not progress. If there are host defence problems, or there is a change in the quantity or quality of the microbial challenge, causing either end of the see-saw to tip, then the balance is upset and disease can progress resulting in periodontal tissue destruction (Fig 2-2).

Fig 2-1 Transition from reversible gingivitis to irreversible periodontitis.

Fig 2-2 The delicate balance between microbial activity and host defences, which maintains periodontal tissue health. Such equilibrium may easily be disrupted, leading to inflammation and tissue damage.

The Nature of Plaque

Biofilm

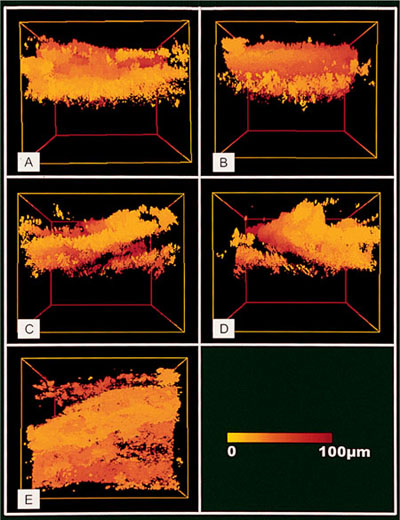

Plaque is a biofilm comprising a complex microbial community in a matrix of polymers of bacterial and salivary origin. It has a complex three-dimensional structure that serves to protect it from the host’s defence mechanisms and from antimicrobial agents (Fig 2-3). Supragingival plaque comprises approximately 50% matrix, and the plaque bacteria tend to be Gram-positive cocci and rods, which are largely aerobic unless the plaque layer is thick. In contrast, although it develops by extension from supragingival plaque, subgingival plaque has very little matrix, and survives at a much lower oxygen concentration. As the subgingival plaque matures in a highly anaerobic environment, the constituent microflora shifts and harbours an increasing proportion of Gram-negative rods and spirochaetes.

Fig 2-3 Biofilm: three-dimensional colour-coded reconstruction of intact human plaque based on a series of 200 xy reflectance images taken at 0.6μm intervals from the surface of the plaque to the enamel surface. Variations in plaque density are apparent and channels can be seen running through the biofilm (bright yellow, closest and dark red (100μm), distant).

Over 400 microbial species have been detected in the oral environment, but only a relatively small number have been specifically implicated in the periodontal disease process. There are three hypotheses of how plaque causes periodontal disease:

-

Specific plaque hypothesis.

-

Non-specific plaque hypothesis.

-

Ecological plaque hypothesis.

Specific plaque hypothesis

According to this hypothesis, individual bacterial species are responsible for inflammatory periodontal disease, for example, as is the case with tuberculosis. Over a century ago, Koch put forward the postulates that set out the various requirements for microbial specificity to be attributed in a disease. Thus, in the specific plaque hypothesis, the clinical implications for periodontal treatment are two-fold:

-

Treatment should be directed towards elimination of the pathogen and prevention of re-establishment.

-

Plaque control would not be necessary, since plaque without the pathogen would be non-pathogenic.

Although several pathogens have been implicated since the 1990s (Box 2-1), none has satisfied all of Koch’s postulates.

Box 2-1

Suspected Periodontal Pathogens

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans

Bacteroides forsythus

Campylobacter rectus

Eikonella corrodens

Fusobacterium nucleatum

Porphyromonas gingivalis

Prevotella intermedia

Peptostreptococcus micros

Spirochaetes, e.g. Treponema denticola

Very few periodontal conditions are associated with specific pathogens. Nevertheless, A. actinomycetemcomitans has been strongly implicated in localised aggressive periodontitis. It possesses many virulence factors some of which are specifically designed to evade host defence systems. Elimination of A. actinomycetemcomitans can be difficult and often requires mechanical therapy with adjunctive systemic antibiotic treatment. Studies have shown that successful therapy is associated with elimination of this organism. Fusiforms, spirochaetes and P. intermedia have been associated with necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (NUG).

Non-specific plaque hypothesis

This hypothesis suggests that in the absence of effective plaque control, the indigenous plaque bacteria colonise the gingival sulcus and form plaque. Inflammatory periodontal disease develops when the combined effects of the total microbial challenge overcome the host’s defence mechanisms. All plaque bacteria are thought to have some virulence factors capable of causing gingival inflammation and subsequently periodontal destruction. Implications for treatment are:

-

Total plaque control is necessary in the prevention of the plaque-induced periodontal diseases.

-

Patient’s oral hygiene must be effective.

-

Professional scaling and root surface debridement must be meticulous.

This hypothesis does not explain the variations in pathogenic potential or the different types of periodontal disease. It does not address why some patients never progress from gingivitis to periodontitis and why some sites remain stable while others progress. Its application, therefore, is limited to chronic gingivitis.

Ecological plaque hypothesis

Haffajee and colleagues in 1991, discussed an “environmental” plaque model and Marsh (1994) subsequently proposed that dental plaque forms naturally on the teeth and helps the host’s defence systems by preventing colonisation of exogenous and often pathogenic (non-resident) species. Plaque accumulation around the gingival margin leads to an inflammatory response and increased gingival crevicular fluid flow, the constituents of which can affect the local environment and change the subgingival plaque ecology, this shifts from mainly Gram-positive to obligatory anaerobic asaccharolytic Gram-negative bacteria. When the microbial homeostasis is altered, these sites are susceptible to periodontal disease. The prevailing treatment consideration involves inhibition of periodontal pathogens:

-

directly (by subduing the pathogens) or

-

indirectly (by interfering with factors that drive the transition, e.g. use of anti-inflammatory drugs).

No single plaque hypothesis has so far been able to explain fully plaque’s role in the disease process, but the ecological hypothesis is the one which most agree best fits chronic periodontitis.

Host defence systems

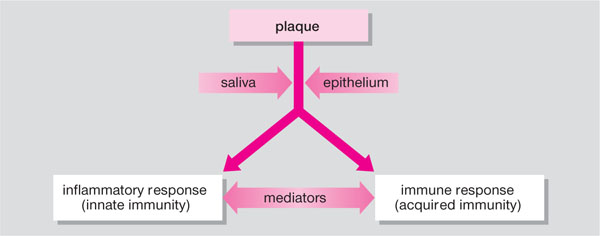

The young patient’s defence mechanisms are critical, as they keep plaque bacteria and their products out of the periodontium and destroy any that do manage to get through. There are five key defence systems (Fig 2-4):

-

saliva

-

epithelium

-

inflammatory response (innate immunity)

-

immune response (acquired specific immunity)

-

soluble mediators of the inflammatory immune response.

Fig 2-4 Host defences.

Saliva

Saliva protects only those parts of the periodontium where it can gain access within the so-called salivary domain. In contrast, host defence mechanisms in the gingival crevice and periodontal pocket are deemed to be in the crevi/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses