Assessing patients

2.1 History

Medical history

• Cardiovascular (heart or chest problems).

• Respiratory (chest trouble).

• Central nervous system (fits, faints or epilepsy).

• Current medical treatment: a negative response should be further confirmed by asking whether the patient has visited their general practitioner recently.

• Current and recent drug therapy.

• Past medical history: previous occurrences of hospitalisation or medical care.

• History of jaundice or hepatitis.

• Any other current health problems: a negative response can be confirmed, with a final ‘so you are fit and well?’

See Chapter 3 for a more detailed discussion of the medical aspects of dental care.

2.2 Extraoral examination

Lymph node examination

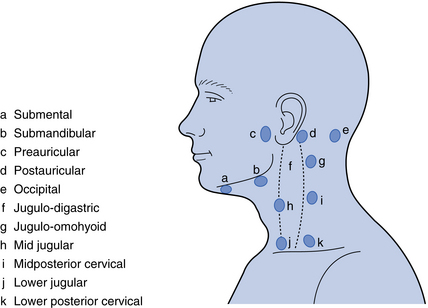

The major lymph nodes of the maxillofacial region and neck are shown in Fig. 2.1. The submental, submandibular and the internal jugular nodes (jugulo-digastric and jugulo-omohyoid node being the largest) are of particular importance because these receive lymph drainage from the oral cavity. Examination of the nodes should be systematic, although the order of examination is not critically important. To palpate the nodes, the examiner should stand behind the patient while he/she is seated in an upright position. Use both hands (left hand for the left side of the patient, etc.). A common sequence would be to start in the submental region, working back to the submandibular nodes then further back to the jugulo-digastric node (see Fig. 2.1). Then continue by palpation of the parotid region downwards to the retromandibular area and down the cervical chain of nodes. When a node is perceived as enlarged, record the texture: a hard node of a metastasising malignancy contrasts well with a tender, softer node in an inflammatory process.

Temporomandibular joint

A detailed examination of the TMJ is probably only needed when a specific problem is suspected from the history. Details of examination of this joint and the associated musculature is given in Chapter 15.

Salivary glands

As with the TMJ, examination of the salivary glands is only required when the history suggests this is relevant. Chapter 13 describes the examination of the major salivary glands.

Problem-specific examination

Paraesthesia/anaesthesia

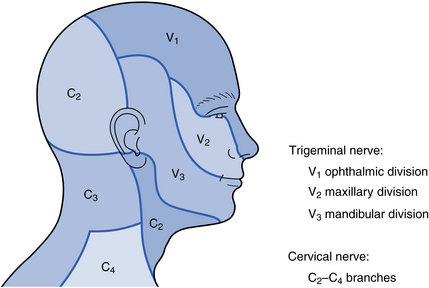

The extent of the area of paraesthesia or anaesthesia will tell you the particular nerve, or branch of a nerve, involved (Fig. 2.2). This will, in turn, inform you about the possible location of the underlying lesion. For example, a patient with disturbed sensation of the upper lip has a lesion affecting the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve. If this is the sole site of sensory deficit, it suggests a lesion closer to the terminal branches of this cranial nerve (e.g. in the maxillary sinus). In contrast, if sensory deficiencies are simultaneously present in other branches of the nerve, it suggests that the lesion is more centrally located.

Paralysis/motor disturbance

While paralysis or motor disturbance may be reported as a symptom by the patient, it may initially be identified during an examination. In the maxillofacial region, the motor nerves that are likely to be under consideration are the facial nerve, the hypoglossal nerve and the nerves controlling the muscles that move the eyes.

Disturbance in function of the facial nerve will result in effects on the muscles of facial expression. Paralysis of the lower face indicates an upper motor neurone lesion (stroke, cerebral tumour or trauma). Paralysis of all the facial muscles (on the affected side) indicates a lower motor neurone lesion. The latter is seen in a large number of conditions but, for the dentist, important causes include Bell’s palsy (Fig. 2.3), parotid tumours, a misplaced inferior dental local anaesthetic and trauma.

Fig. 2.3 Patient with Bell’s palsy.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses