CHAPTER 17 THE LAW AND DENTAL PRACTICE: PROTECTING THE HEALTH OF THE COMMUNITY

Protecting the Health of the Community

Legislation designed to protect the public from unqualified health practitioners began in the early part of the nineteenth century. Before that time the principle of free enterprise enabled anyone to “treat” the sick and charge a fee for the service they provided. Many state legislatures believed that some form of qualification should be required to permit persons to engage in the practice of medicine and dentistry. Encouragement in general came from members of professional societies. Many leaders of the dental profession in the early and mid-nineteenth century were located in Baltimore. One was Dr. Shearjashub Spooner, who in speaking before the dental society in 1838 stated, “The dental profession should be protected by legislative enactment: every person before he be permitted to practice it, should serve a term of pupilage and pass an examination before a competent board of dentists.”1 Eleasar Parmly, another leader in the dental society, agreed. “If the legislature will do nothing more than merely to regulate the conditions by which members shall be admitted to practice…it would serve, at least, to draw a line of distinction, which the public would understand, between the regular members of the profession, and the quacks who disgrace it.”1 Chapin Harris, at the opening of the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, stated, “Filled as the ranks of the profession are, with individuals who have never learned the first rudiments…it will doubtless require some time to effect the wished reformation, and [it] will only be accomplished [by fixing] a line of distinction between the competent and the incompetent. It is necessary that there should be some test of qualification by bodies qualified and regularly appointed for the duty.” He later stated, “The community at large have experienced too much of the bad effects growing out of the ignorance of dental practitioners.”1 It was clear that the leaders in the profession were bent on having some form of regulation designed to protect the public from the unskilled, untrained, and unqualified.

Laws regulating the practice of dentistry began in 1841 in Alabama. However, the law was rudimentary and only nominally regulated the practice of the profession. In 1868 Kentucky, New York, and Ohio specified, in detail, the requirements to practice the profession and gave power of enforcement to a government agency. Dr. J. Ben Robinson, in an article published in the Journal of the American Dental Association, reported the following:2

An early case challenging a law limiting health practice to those who were qualified by law was brought before the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts in 1835.3 The court was to decide if a “bonesetter” fell within the law, and further, whether the law was constitutional. As to the first, the court found the following:

The court, in deciding the law to be constitutional, went on to state the following:

In 1889 a case that began in West Virginia was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.4 It was a case in which a physician was found guilty of violating the law regulating medical practice. He challenged the law as to whether he met the conditions of the law in obtaining a license to practice, which had been denied, and whether the law was constitutional. In deciding, the court stated the following:

As with physicians, challenges by dentists found their way into the courts. In 1889 the Supreme Court of Minnesota had the following to say about the state’s law regulating dental practice:5

The power rests on the right to protect the public against the injurious consequences likely to result from allowing persons to practice those professions who do not possess the special qualifications essential to enable the practitioner to practice the profession with safety to those who employ him. The same reasons apply with equal force to the profession of dentistry, which is but a branch of the medical profession.

In concluding, the court stated the following:

In 1914 the Court of Appeals of New York was asked to rule on the validity of the law regulating dental practice.6 In its ruling the court stated the following:

COURTS AND LEGAL PRECEDENTS

Courts

Courts are classified in many ways: as to their organization, whether lower or upper; their geographic jurisdiction, based on where they sit; their subject matter jurisdiction, criminal or civil; trial or appellate; and so on. For purposes of this chapter, lower and upper, that is, trial and appellate, are of concern. The issue is how legal precedent is set and how it affects the health professions in general and dental practice in particular.

When an appellate court decides a case, precedent law is established. All lower courts within the geographic jurisdiction of the appellate court are required to follow the precedent established by the appellate court. If the lower court does not and the case is appealed, the decision of the lower court will be reversed. If the case is not appealed, the decision of the lower court is final, notwithstanding the fact that in arriving at the decision precedent law was ignored. It is important to remember that only appellate courts establish precedent and that no one, not even the most experienced attorney, can predict with any degree of certainty how a judge or jury will decide a case. Fifty percent of all lawyers representing clients end up on the losing side and are proved wrong by either a judge or jury or by an appellate court.

CAVEATS IN RISK MANAGEMENT AND THE LAW

The United States has 51 jurisdictions: 50 states and the federal government. Each of the 50 states has exercised its right to regulate the health professions, including dentistry. In addition, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and the District of Columbia also regulate health practices. The federal government regulates some elements of health practice. Therefore 54 separate jurisdictions regulate the practice of dentistry. Except for federal regulations that apply to practitioners in all states, each jurisdiction has independent regulations. Except for some federal laws, there is no generic law in the United States. There are, however, legal principles that apply nationwide. For example, the legal principle of the statute of limitations is the same in all jurisdictions, but the statute may begin to run at different times and for different lengths of time in each individual jurisdiction.

Loss Without Fault

Another artificial legal concept is “loss without fault.” It evolved from a study I conducted in the early 1980s during the crisis in dental malpractice litigation. Four hundred cases in which a dentist was accused of malpractice were tracked from the initial service of suit papers to the closing of the case. The results were that in 80% of 400 cases brought against dentists, the insurance company, on the advice of a panel of dental experts and an attorney experienced in dental malpractice litigation, sought settlement before trial because it was apparent that the case could not successfully be defended. In only 20% of the cases the panel believed that the dentist was guilty of malpractice. In 60% of the cases in which settlement was sought, the dental experts were of the opinion that no negligence was present. This 60% represents “loss without fault”–no malpractice, but little or no chance of successfully defending the suit. Looking at the data from another perspective, of 400 cases alleging malpractice brought against dentists, in 80% there was no evidence of malpractice, but according to the expert panel in only 20% could the suit be successfully defended. Loss without fault is the foundation of much of risk management.

REGULATION OF DENTAL PRACTICE

A combination of the statutes and the rules and regulations makes up the body of dental BLL, commonly referred to as the Dental Practice Act. However, in all jurisdictions, many other laws affect the practice of dentistry. These may be found in the public health law, the sanitary code, the education law, and others. The practitioner should be aware that the laws regulating dental practice are spread throughout the statutes and administrative laws of the state. In addition, a multitude of federal laws exercise control over dental practice. The old adage that ignorance of the law is no excuse should not be ignored.

LEGAL VULNERABILITY IN DENTAL PRACTICE

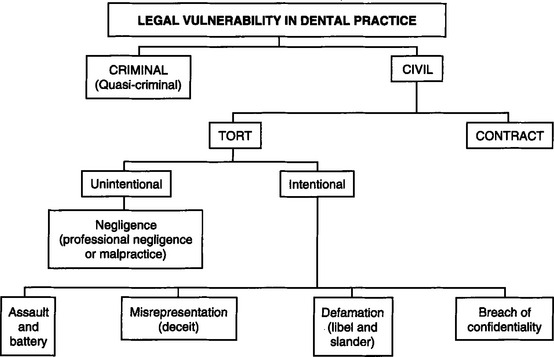

Legal vulnerability in dental practice may be divided into two broad categories: criminal and civil. Each broad category has subcategories, as shown in Fig. 17-1. The intentional torts listed on the chart are those most frequently associated with dental practice. False imprisonment, abuse of process, trespass to real property, conversion, interference with performance of a contract, and others are recognized in law but have little relevance in dental practice.

CRIMINAL AND QUASI-CRIMINAL VULNERABILITY

Violations of statutory law are termed crimes. They constitute acts that are deemed by the government to be against the public interest. They may be defined as misdemeanors or felonies. Violations of that part of the Dental Practice Act that is statutory, enacted by the legislature, also are classified as crimes and may include penalties such as loss or suspension of license, mandatory psychiatric counseling, drug rehabilitation, mandatory continuing education, fines, or even jail. If the legislature declares the violation a misdemeanor, the jail sentence may be less than if it classifies the violation a felony. In New York, for instance, aiding or abetting an unlicensed person to perform a service that requires a license is a class E felony, punishable by up to 3 years in jail. In other jurisdictions it may classified as a misdemeanor.

The risk management admonition is as follows: Know the law, don’t break it!

THE DOCTOR-PATIENT CONTRACT

When the Doctor-Patient Relationship Begins

The legal foundation of the doctor-patient relationship is contract law. At the moment a dentist expresses a professional opinion to an individual who has reason to rely on the opinion, the doctor-patient relationship begins, and the doctor is burdened with implied warranties (duties). The fact that no fee is involved does not affect the relationship that attaches to the contract or the duties.

When the Doctor-Patient Relationship Ends

The relationship ends when any of the following takes place:

The dentist’s unilaterally terminating the relationship may support a claim of abandonment by the patient unless the dentist follows a procedure acceptable to the courts. Abandoning a patient before the agreed treatment is completed is unethical, and in some jurisdictions it is a violation of BLL.7,8 In all jurisdictions abandonment may lead to a civil suit.

The major causes that contribute to a decision to terminate treatment before it is complete are as follows: (1) the patient has not fulfilled the payment agreement, (2) the patient has not cooperated in keeping appointments, (3) the patient has not complied with home care instructions, and (4) there has been a breakdown in interpersonal relationships. Any of these is ample justification for the dentist to terminate treatment.

GUARANTEES

Guarantees, or assurances of outcomes, made by the dentist or an employee constitute an express term in the agreement. In some jurisdictions guarantees attached to health care are illegal.9 You may be held to a guarantee even if the treatment meets acceptable standards of care. A statement made by a dentist to the patient that the patient will be satisfied with the treatment is a guarantee. If the patient is not satisfied, the dentist has breached the contract despite the excellent quality of the service.

The risk management rule is as follows: Never guarantee a result.

IMPLIED WARRANTIES (DUTIES) OWED BY THE DOCTOR

Attached to the doctor-patient relationship are additional duties that are implied, unless the express terms serve to void or modify them. They are enforceable although not written or stated. Over the years the courts have identified many of these implied duties. Some of the more important ones are included in the list that follows.

In accepting a patient for care, the dentist warrants that he or she will do the following:

IMPLIED DUTIES OWED BY THE PATIENT

Depending on the treatment, additional warranties may exist.

For purposes of risk management: If any of the warranties is broken by the patient, this should be noted on the patient’s record, and consideration should be given to discontinuing the care of the noncompliant patient.

RISK REDUCTION IN THE TRANSMISSION OF BLOOD-BORNE INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Use of Barrier Techniques

In addition, some states have mandated the use of these and other barrier techniques in the treatment of all patients. Some have addressed the issue of hepatitis B carrier testing and regular monitoring of sterilization equipment.

Dentists should remain current with the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards, American Dental Association (ADA) recommendations, and local law to determine what measures must be taken to prevent transmission of blood-borne diseases. Failure to meet the standards exposes the dentist to legal risk of action by a government agency for violation of the law and civil action by an individual (i.e., patient, staff) who contracted a blood-borne disease traced to the dentist’s office. (For more information about the treatment of patients with transmissible diseases, see Chapter 9.)

Following are contact agencies from which information and their rules may be obtained:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses