Chapter 17 Maxillary Arch Implant Considerations: Fixed and Overdenture Prostheses

More than 18 million people, or 10.5% of the adult population of the United States, are completely edentulous. Maxillary dentures usually are tolerated better by patients than their mandibular counterparts. As such, many treatment plans initially concentrate on the problems associated with the mandibular denture (Figure 17-1). However, once the patient enjoys a stable, retentive, and perhaps fixed mandibular prosthesis, often the patient’s attention is brought to the inadequacies of the maxillary prosthesis. In addition to this segment of the population without any teeth, 7% of the adult population wears a maxillary denture opposing some remaining mandibular teeth. This means that 17% of the U.S. population (30 million adults) have no natural maxillary teeth.

EDENTULOUS ANTERIOR MAXILLA

In a 20-year review of the literature compiled by Goodacre et al., restorations associated with the edentulous maxilla have the highest early implant failure rate compared with any other situation. In this review, overdentures in the maxillary arch averaged 19% implant failure. Fixed prostheses in the edentulous maxilla had an early implant failure of 10%. In comparison, mandibular overdentures or fixed restorations demonstrated a 3% implant failure rate.1

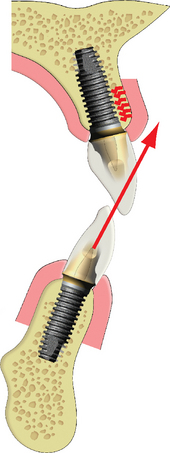

Several factors affect the condition of the edentulous maxilla and may result in a decrease in implant survival or an increase in prosthetic complications. The facial cortical plate of the premaxilla is thin over the roots of the teeth and may be resorbed from periodontal disease or is often fractured during the extraction of these teeth. In addition, the facial cortical plate rapidly resorbs during initial bone remodeling, and the anterior ridge loses 25% of its width within the first year after tooth loss and 40% to 50% over 1 year, mostly at the expense of the labial plate. As a result, the residual available bone migrates to a more palatal position.2–7

The patient is more likely to wear and functionally accommodate a maxillary complete denture compared with its mandibular counterpart. The greater retention, support, and stability compared with the lower restoration are well documented. As such, the patient often is able to wear the maxillary removable prosthesis for longer periods before complications arise. From a patient’s perspective, the need to replace the denture is more related to a desire for a fixed restoration as the motivating factor. By the time the patient notices problems of stability and retention caused by resorption of the premaxilla, the maxillary bone often has advanced atrophy and may be Division C–h or D in volume. Therefore the completely edentulous, anterior bony ridge is often inadequate for ideal endosteal implant insertion.

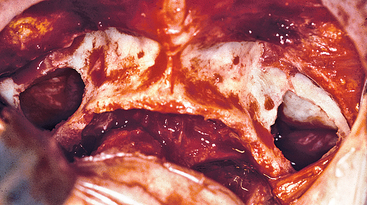

In most patients with available bone, the bone is less dense in the anterior maxilla than in the anterior mandible, where a dense cortical layer surrounds coarse trabeculae of adequate bone strength to provide implant support. In contrast, the maxilla presents thin porous bone on the labial aspect, very thin porous cortical bone on the floor of the nasal and sinus region, and a more dense cortical bone on the palatal aspect.8,9 The trabecular bone is usually fine and is less dense than the anterior region of the mandible. The trabecular bone of D3, often found in the maxilla, is 45% to 65% weaker than the trabecular bone of D2, usually found in the anterior mandible.

From a biomechanical perspective, the implant-restored anterior maxilla is often the weakest section compared with other regions of the mouth. Compromised anatomical conditions and their consequences include the following (Box 17-1):

TREATMENT OPTIONS

The primary reason for a conventional maxillary removable denture is economic reasons or because a patient is unwilling to undergo implant surgery. However, the easiest interim treatment prosthesis for the replacement of several anterior teeth during implant submerged healing is a removable restoration. If bone augmentation is necessary, this prosthesis may need to be used for longer than 1 year before delivery of the final implant restoration.

Sequence of Treatment

Maxillary Labial Lip Position

Whether a denture, an overdenture, or a fixed prosthesis is being fabricated, a full-arch maxillary reconstruction begins with the determination of the facial position of the maxillary incisal edge. Its modification at a later step may alter all other measurements. A baseplate and wax rim may determine the labial contour of the maxillary lip. Most often the facial surfaces of the central incisors are 12.5 mm from the most posterior aspect of the incisive papilla.10,11 The wax rim is initially positioned with this in mind. The farther forward the labial flange and teeth position, the higher the resting position of the lip and the greater the incisal edge exposure. The philtrum of the lip should have a visible depression in the midline under the nose. If the philtrum is too flat, the lip is extended too far, and wax should be removed from the labial aspect of the wax rim.

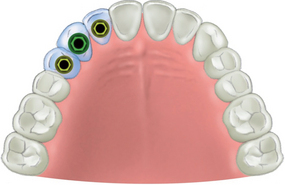

The labial position of the lip in relationship to the premaxilla is the primary criterion to determine whether a fixed restoration, a bone graft and fixed restoration, or a maxillary overdenture is indicated. When the labial position of the wax rim is forward of the residual ridge more than 5 mm, a bone graft prior to implants is required for a fixed restoration, or a maxillary overdenture is considered (Figure 17-5). The maxillary anterior region with multiple teeth missing often is restored with an overdenture or FP-3 prosthesis.

Key Implant Positions

Once the prosthesis type and tooth position are determined, the patient force factors and bone density in the implant sites are evaluated. The key implant positions are then determined for the maxillary restoration.12–14 An important parameter in treatment planning is to provide adequate biomechanical position and surface area of support for the load transmitted to the prosthesis. Four guidelines were presented in Chapter 8 for key implant positions in an implant prosthesis include:

Guideline 3: The Canine and First Molar Site

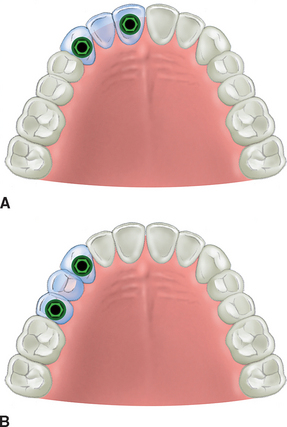

A fixed prosthesis replacing a canine tooth is at greater risk than most any other tooth in the mouth. The maxillary lateral incisor is the weakest anterior tooth, and the first premolar is often the weakest posterior tooth. A traditional prosthodontic axiom indicates a fixed prosthesis is contraindicated when a canine and two or more adjacent teeth are missing.15 Therefore if a patient desires a fixed restoration, implants are required whenever the following adjacent teeth are missing: (1) the first premolar, canine, and lateral incisor (Figure 17-6); (2) the canine, lateral incisor, and central incisor (Figure 17-7, A); and (3) the canine, first premolar, and second premolar (Figure 17-7, B).

A tooth-supported prosthesis is less at risk than an implant-supported restoration when the canine and two adjacent teeth are missing. Because teeth are more mobile than implants, a stress relief mechanism reduces the flexure, force, and effect of an angled force. Despite this, it is contraindicated to design three pontics in a fixed prosthesis whenever the natural canine and two adjacent teeth are missing. Therefore, under these conditions with implant treatment plans, at least two implants are indicated to support an independent fixed restoration (usually in the terminal positions of the span to eliminate cantilever forces) (Figure 17-8).

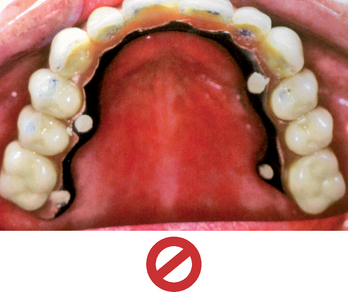

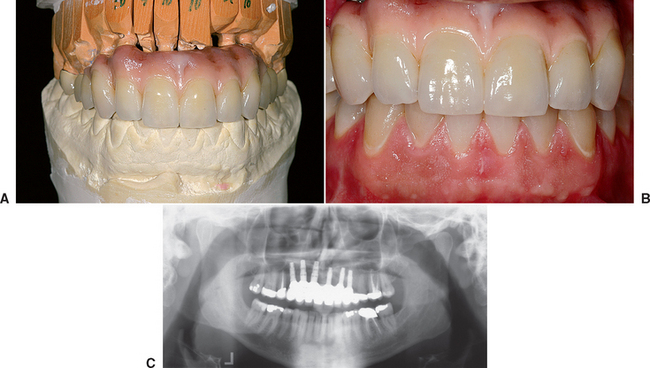

Using the missing canine and two adjacent natural teeth guideline, a fixed prosthesis is also contraindicated when missing a right canine, right lateral incisor, right central incisor, left central incisor, left lateral incisor, and left canine without considerable anterior implant support (Figure 17-9). Yet in some improper treatment plans, implants are placed in each posterior maxillary quadrant and a fixed restoration with six pontics is fabricated to replace the anterior teeth (Figure 17-10). Apparently the rationales for violating the prosthetic guidelines established in the literature for teeth are the following:

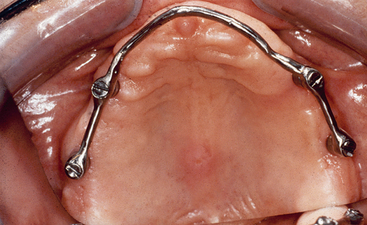

Posterior implants (premolar and molar) without implant support in the premaxilla are sometimes connected with a full-arch bar for a maxillary overdenture. When a bar extends from molar to molar around an arch, the overdenture prosthesis is completely implant supported (RP-4), because it does not move during function or parafunction. As such, the overdenture acts as a fixed restoration (Figure 17-12). The removable implant prosthesis under these conditions should have the same implant support as a complete arch fixed restoration (not less).

Guideline 4: Five-Sided Arch

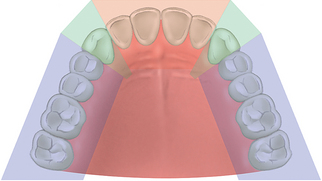

The maxillary arch may be divided into five segments, similar to an open pentagon (Figure 17-13). The central and lateral incisors represent one segment, each canine a separate segment, and the posterior premolars and molars individual segments. In other words, each segment is essentially a straight line, with little resistance to lateral forces. However, when splinted together, an arch form dynamic becomes evident.

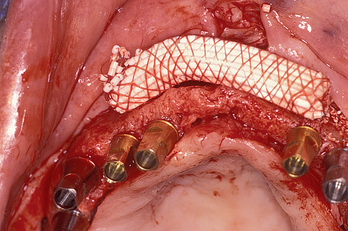

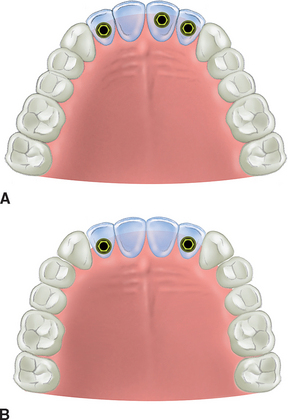

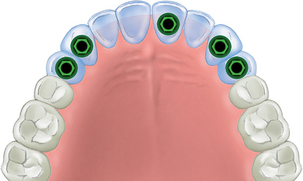

At least one implant should be placed in each of the five sections missing teeth and then splinted together when replacing multiple adjacent teeth missing in the maxilla. At least three implants usually are required to replace the anterior six teeth in the premaxilla: one in each canine position and one in any of the four incisor positions.12–16 When posterior teeth are also missing, additional posterior implants are required (Figures 17-14 and 17-15).

Previous studies by Bidez and Misch have shown that the force distributed over three abutments results in less localized stress to the crestal bone than two abutments.17 Because these three elements are aligned along an arch, connecting at least three segments creates a tripod effect and provides an anteroposterior distance (A-P spread) with mechanical properties superior to a straight line and with greater resistance to lateral forces. The A-P distance for the anterior cantilevers in the premaxilla restoration corresponds to the distance between the center of the most distal implants on each side (in the splint) and the anterior aspect of the most anterior implant.

A poor treatment option for fully edentulous maxillae is the placement of implants in each posterior quadrant with independent bar segments and an overdenture. This treatment option is prone to failure. The maxillary overdenture rocks back and forth during excursions (if not, the overdenture is really a fixed restoration). The posterior implants are in a straight line and cannot resist the lateral forces. Eventually, almost all the implants on one side are lost. Maxillary complete prostheses and overdentures have a greater incidence of implant failure and complications than mandibular counterparts.1,18,19 These observations further emphasize the need for more implants and fewer pontics in the restoration of a maxilla compared with the mandible.

Premaxilla Arch Form

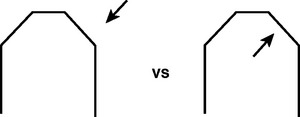

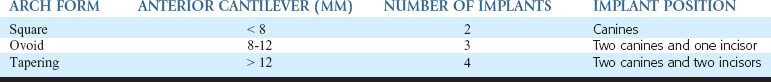

The arch form of the maxilla influences the fixed prosthesis treatment plan of the edentulous premaxilla. Three typical dental arch forms for the maxilla are square, ovoid, and tapering. As a consequence of bone resorption, the edentulous ridge arch form may be different from the dentate arch form. The dental arch form of the patient is determined by the final teeth position in the premaxilla and not the arch shape of the residual ridge. A residual ridge may appear square because of resorption or trauma. However, the final teeth position may need to be cantilevered facially with the final prosthesis. In other words, a dental ovoid arch form may be needed to restore a residual edentulous square arch form. The number and position of implants are related to the arch form of the final dentition (restoration), not the existing edentulous arch form (Table 17-1).

The dental arch form in the anterior maxilla is determined by the distance from two horizontal lines. The first line is drawn from one canine incisal edge tip to the other. This line most often bisects the incisive papilla. The second line is drawn parallel to the first line, along the facial position of the anterior teeth (Figure 17-16). When the distance between these two lines is less than 8 mm, a square dental arch form is present. When the distance between />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses