17

Childhood impairment and disability

J.H. Nunn

Chapter contents

17.3 Physical impairment—cerebral palsy

17.4 Physical impairment—spina bifida

17.5 Physical impairment—muscular dystrophy

17.6 Other musculoskeletal impairments

17.7 Blindness and visual impairment

17.8 Deafness and hearing impairment

17.1 Introduction

An impairment becomes a disability for a child only if he/she is unable to carry out the normal activities of his/her peer group. For example, a child who has broken an arm is temporarily ‘disabled’ by not being able to eat and write in the normal way. However, impairment is a permanent feature in the lives of some children, although it may become a disability only if they are unable to take part in everyday activities, such as communicating with others, climbing stairs, and toothbrushing. A more contemporary view is one that moves away from the medicalization of impairment to a consideration of ability and functioning, enshrined in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Impairment. In this definition, a number of domains are classified from body, individual, and societal perspectives. This approach is less stigmatizing, and more enabling of children with impairments.

1. The oral health of some children with disabilities is different from that of their healthy peers—for example, the greater prevalence of periodontal disease in people with Down syndrome and of tooth-wear in those with cerebral palsy.

2. The prevention of dental disease in disabled children needs to be a higher priority than for so-called normal peers because dental disease, its sequelae, or its treatment may be life-threatening—for example, the risk of infective endocarditis from oral organisms in children with significant congenital heart defects (Fig. 17.1).

3. Treatment planning and the provision of dental care may need to be modified in view of the patient’s capabilities, likely future cooperation, and home care—for example, the feasibility of providing a resin-bonded bridge for a teenager with cerebral palsy, poorly controlled epilepsy, and inadequate home oral care.

In the light of these considerations, do such children need special dental care? Most of the studies which have been undertaken on disabled children have indicated that the majority can in fact be treated in a dental surgery in the normal way, together with the rest of their family. However, recognizing that the complex needs of some people with special health care requirements may need targeted services, the public dental service in the UK uses a tool that identifies the particular aspects of an individual’s needs which make access to specialist care a priority and, importantly, identifies that additional resources will be required to meet the needs and demands of such patients (British Dental Association 2010). (See Key Points 17.1.)

Normality is desirable, provided that the disabled person actually receives good dental care. The evidence from many studies is that, although the overall caries experience is similar between disabled children and their so-called normal contemporaries, the type of treatment they have experienced is different. Disabled children have similar levels of untreated decay, but more missing teeth and fewer restored teeth. A minority of children with complex disabilities need special facilities, usually only available in dental or general hospitals, or from specialized community dental clinics. What is needed by all patients with disabilities is a very aggressive approach to the prevention of dental disease. Because of the potential for dental disease, or its treatment, to disable an impaired child, priority must be given to preventive dental care for such individuals from a very young age.

Figure 17.1 A 13-year-old boy with Down syndrome and gross caries, who was prevented from going on a combined heart and lung transplant register, as well as a renal transplant register, because of his dental disease.

Children with a significant degree of impairment are termed ‘children with special educational needs’ or ‘children with learning difficulties’. These terms, used synonymously, encompass a wide variety of impairments, but three main areas—intellectual, physical, and sensory impairments—predominate and will now be considered in more detail. However, it is important to stress that impairment does not always present as a discrete entity; in any population of affected children, at least a quarter of the group will be multiply impaired, making it difficult to assign a ‘label’ to that child’s overall impairment. Medical compromise, considered in more detail in Chapter 16, may also be imposed on these impairments. The ways in which some of these conditions present to a dentist are given below, together with the dental management issues relevant to each. Many of the issues raised are, of course, common to a number of impairments.

17.2 Intellectual impairment

The causes of intellectual impairment are numerous, and for many children a cause for their disability may never be identified. Approximately 25 per 1000 of the child population are affected and, as with other impairments, the majority will be males. Children with intellectual impairment can be divided broadly into those who are mentally retarded and those who have a learning difficulty. These are broad groups, often without a well-defined aetiology or consistent presenting features, but there are two distinct subgroups where the cause is known and the features are well described, namely Down syndrome and fragile X syndrome. Intellectual impairment may be present in some children with cerebral palsy and those who have suffered birth anoxia and severe infections (e.g. meningitis and rubella). Intellectual impairment is also a feature of autism, microcephaly, and metabolic disorders (e.g. phenylketonuria), and may also be acquired after significant trauma. Not every condition will have specific dental features like Down syndrome, but an understanding of the underlying impairment will help the dentist plan treatment more effectively.

Mental retardation, pervasive developmental disorders (autism and schizophrenia), learning disabilities, dyslexia, attention-deficit disorders, and hyperactivity are all controversial categories whose definition and processes of assessment are not universally agreed. (See Key Points 17.2.)

Mental retardation

This is sometimes called mental handicap, mental subnormality, or mental deficiency. It is a general category characterized by low intelligence, failure of adaptation, and early age of onset. Low general intelligence is the main characteristic. Affected children are slow in their general mental development, and they may have difficulties in attention, perception, memory, and thinking. They may be stronger in some skills than others (e.g. music and computing), but generally they are of low intellectual attainment. Children with low intelligence are not called mentally retarded unless they also have some problem in adaptation, i.e. they are unlikely to be able to live independently and will always depend on others as a source of income and support for daily living. According to IQ levels, five levels are traditionally described. The simplicity of the classification is somewhat illusory with great individual differences among people with mental retardation. (See Key Points 17.3.)

Down syndrome

Down syndrome is a chromosomal disorder, trisomy 21, with distinct clinical features. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 600 births, but there is variation with maternal age, so that at 40 years of age the incidence is about 1 in 40 births. However, the numbers seen in any one country will vary depending on the prevailing attitude towards prenatal screening and termination. The general physical features associated with Down syndrome are a greater predisposition to cardiac defects, myeloid leukaemia, and infective hepatitis (especially in institutionalized males), although most children will have been vaccinated against viral forms. Coeliac disease and thyroid disorders are also clinical features of this condition. Increasingly, a form of early dementia, entitled disintegrative disorder, is being recognized in adolescents with Down syndrome. The features seen are a progressive loss of skills, both cognitive and physical, and this has obvious relevance in dentistry because of the impact on personal oral care.

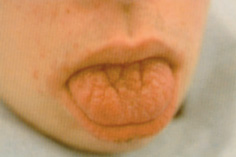

Varying degrees of intellectual impairment occur, and upper respiratory tract infections and an inability to withstand infections generally are common. Physically, predominant features are a small rounded face with an underdeveloped mid-face (Fig. 17.2), especially of the nasal bridge, an upward slant of the eyes with prominent epicanthic folds, squints, cataracts, and Brushfield spots on the iris. The hands of children with Down syndrome are stubby, with a pronounced transverse palmar crease. Intra-orally the tongue is large, protruding, and sometimes heavily fissured (Fig. 17.3). The palate may be high-vaulted and narrow. There is usually a delay in the exfoliation of primary teeth and the eruption of permanent teeth, while some teeth may be congenitally missing. Teeth that erupt are often microdont and/or hypoplastic (Fig. 17.4). There is a high prevalence of periodontal disease in the anterior alveolar segments, especially in the mandible. This is probably due to impaired phagocyte function in neutrophils and monocytes combined with poor oral hygiene. Other factors implicated in the pathophysiology of the extensive inflammation seen in Down syndrome patients are enhanced prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production and increased activity of plasminogen activators, and thus collagenase activity. (See Key Points 17.4.)

Fragile X syndrome

Next to Down syndrome, this is the most common cause of intellectual impairment. This disorder is largely under-diagnosed; and people who have been classified as having ‘mental handicap of unknown origin’, especially if they are male, probably have fragile X syndrome. The condition is of particular significance because a high proportion of affected individuals have congenital heart defects, usually mitral valve prolapse, which may require antibiotic prophylaxis. Although males are predominantly affected, milder versions of the disability may be seen in females.

Figure 17.2 Lateral view of a Down syndrome child, showing mid-face hypoplasia.

Figure 17.3 The protruberant fissured tongue of an adolescent with Down syndrome.

Figure 17.4 A Down syndrome patient with marked dental hypoplasia, conical teeth, and hypodontia.

Pervasive developmental disorders

This group encompasses autism and childhood schizophrenia. The former is characterized by its early onset, usually before 30 months of age, whereas childhood schizophrenia presents later. They are conditions that represent profound adaptive problems in thinking, language, and social relationships. Autism in particular has the distinctive feature of restricted and stereotypical behaviour patterns. Most children score below normal on IQ testing and thus experience significant developmental delay. The more severely delayed children seem oblivious to their parents or carers, express themselves minimally, show a low level of interest in exploring objects, avoid sounds, and engage in ritualistic behaviour. Children with Asperger’s syndrome display some of the features of autism but may also possess a level of skill in some areas that is well above the average for their peers. These features need to be taken into consideration when attempting dental care, and underline the particular importance of acclimatization and familiarity of routine (rituals) as part of that process.

The causes of autism are unknown but are thought to be prenatal and not social in origin. Much interest was generated in a possible link with MMR vaccine as a possible aetiological factor, but this evidence has since been discredited. A major malformation in the cerebellum has recently been implicated as a possible causative factor. The prevalence of autism ranges from 0.03% to 0.1% with fluctuations that may point to an environmental cause.

Learning difficulties

Learning difficulty is associated with dyslexia, minimal brain damage, attention-deficit disorder, and hyperactivity. All these categories are controversial, mainly because they have been over-extended.

Historically, a child with a learning difficulty has been defined as one whose performance in one academic area is more than 2 years behind that age group’s ability. Thus the impairment is restricted in its range and there is a discrepancy between academic performance and tested general ability. In these two ways a learning difficulty differs from mental retardation because the latter is characterized by general delay and academic performance is usually at the level expected from ability. In practice, learning difficulty has been used to characterize any child with a learning problem who cannot be labelled mentally retarded, no matter how broad the range of impairment or the discrepancy from the tested ability level. This over-extension of the definition has not only increased the apparent prevalence of learning disability but also made the whole area rather confusing.

In general, the prevalence of learning difficulties is estimated on average to be about 4.5%. There is overlap between learning difficulties and other problems, for example higher levels of classroom behavioural problems and an increased risk of delinquency. In part, this accounts for the greater predominance of males in groups with intellectual impairment, as they are more likely than females to be disruptive at school and thus be referred for assessment by educational psychologists.

Dyslexia

This widely discussed form of learning disability is a specific problem with cognition. The broadest definition of dyslexia includes those children whose reading skills are delayed for any reason, and it is usually associated with a number of cognitive deficits. Prevalence varies from 3% to 16% depending on the breadth of the definition and the country. For example, prevalence rates are higher in the USA than they are in Italy, perhaps because of the complexity of the English language compared with Italian!

Minimal brain damage

This category of impairment is used to describe the child who has minor neurological signs, which are often transitory. They are not reliable predictors of future behavioural and educational problems.

Attention-deficit disorder and hyperactivity

These disorders are often confused with one another. Children who cannot sit still are thought to be inattentive in school. A child who does not pay attention often fails to finish activities, acts prematurely or redundantly, infrequently reacts to requests and questions, has difficulties with tasks that require fine discrimination, sustained vigilance, or complex organization, and improves markedly when supervised intensively. A child who is hyperactive engages in excessive standing up, walking, running, and climbing, does not remain seated for long during tasks, frequently makes redundant movements, shifts excessively from one activity to another, and/or often starts talking, asking questions, or making requests. This elevated activity level expresses itself differently at different ages. Inattentive hyperactive children are disturbing to their parents, other children, and professionals such as teachers, doctors, and dentists. They are often judged to be behaviourally disturbed. The variation in definition, age, sex, source of the data, and cultural factors produces prevalence estimates of up to 35%. However, most estimates are under 9% for boys and even less for girls. The aetiology of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is unclear, but may be related to pre-term birth, in which circumstances the prevalence may be as high as 60%.

Emotional and behavioural disorders

There are many manifestations of emotional disorder: fear, anxiety, shyness, aggressive, destructive, or chronically disobedient behaviour, theft, associating with bad companions, and truancy. When parents or teachers believe that these problems interfere with the child’s socialization, they are often referred for professional help. In considering the prevalence of emotional or behavioural disorders, account has to be taken of the very common, seemingly identical, behaviour of healthy children. Eating disorders, which may be of concern to dentists because of self-injurious behaviour as well as dental erosion, are important in the preschool period and, in different ways, in adolescence.

17.2.1 General considerations

Access to care

Segregated special education and institutions, especially in rural areas, were characteristic of services for disabled children until after the Second World War. During the 1950s there was a move towards normalizing the lives of ‘handicapped’ children. This movement set about making major changes in the lives of affected children and adults, but cannot yet be considered as completely successful in many countries. The move to normalization came about largely for ideological, legal, and, probably in some countries, financial reasons.

The philosophy of this movement, which originated in Sweden, centred on the idea that an impaired person should live in an environment as near normal as possible. This involved residing in home-like residences and attending schools, workplaces, and recreational programmes that were part of the community. On the basis of this ideology, many mildly impaired people were moved out of long-stay institutions into community homes. This movement was fostered by the belief that institutionalization retarded emotional and cognitive growth. De-institutionalization would also reduce the state’s expense in maintaining people with impairments, and the onus would be shifted to parents, private charities, and local authorities. Contemporary concepts within this movement are embodied in social role valorization, i.e. the concept of social devaluation of which social exclusion, for whatever reason, is just one aspect.

While most people would agree with the principle of normalization, inadequate funding has produced a less than satisfactory alternative in community care and disastrous consequences for some mentally ill people and those with whom they interact. When many children and adults with impairments were resident in long-stay institutions, the provision of dental services was relatively efficient. With the move to normalization, children were often returned to parents/guardians or housed by social services in homes in the local community, thereby placing an additional burden on these families or carers to organize dental care.

Alongside this programme has been the move to integrate as many children as possible into mainstream education. This may mean that these children are not as readily identifiable as was the case when they attended ‘special schools’ and thus may miss out on the opportunity to receive the prioritized dental care they need. For teenagers, it has become apparent that some managers of the adult training centres that they attend feel that, as part of normalization, their clients should receive ‘normal’ dental care, i.e. from a general dental practitioner. This would be desirable, provided that general dental practitioners were happy to provide this service. The evidence to date is that this is not generally the case. In the meantime, teenagers and young adults could lose out by not continuing to receive the special dental services that the publicly funded service has been able to offer, simply because it is felt by their advocates that this runs contrary to the philosophy of ‘normalization’. In the UK, the genesis of the specialty of Special Care Dentistry has highlighted the potential for greater provision of special healthcare services for such often marginalized groups who, although well cared for as children, often lose out on vital services as adults.

Consent for dental care

A treatment plan for a child (less than 16 years of age in most jurisdictions) requires the consent of a parent before embarking upon active treatment. This is often by implied consent; that is, the parent brings the child to the surgery and the child sits in the chair, the implication being that the parent has consented to treatment. This is no different to the scenario with an impaired child. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child requires that children’s rights are protected, and in this context that cognizance is taken of the child’s views on whether they wish treatment to be carried out. As with any patient, best interests must be protected. Difficulty arises in adolescents with an intellectual impairment who are over the age of consent. In this situation parents or carers are unable to give a valid consent on their charge’s behalf; that is, an adult cannot consent for treatment on behalf of another adult. Dentists would be well advised to obtain a second opinion on their treatment plan before embarking on dental care for an impaired young person who is judged to be incapable of giving their own valid, i.e. informed, consent. This is particularly the case where dental care under general anaesthesia is being contemplated. It is also prudent to discuss the proposed treatment plan and to obtain the agreement for the care that is being suggested from those who have an interest in the patient.

There will be occasions when it will not be possible to easily undertake an examination of a child or adolescent with a profound learning disability. In those circumstances, a decision has to be made as to whether some form of physical intervention, previously termed restraint, may need to be used. The clinician must decide, on the basis of a number of factors, what is the best way forward. At all times, as part of the dentist’s duty of care, he/she must act in the patient’s best interest in reaching a decision as to whether to use some form of physical intervention. This decision must be taken in the light of a number of factors, as listed in Key Points 17.5 (modified after Shuman and Bebeau (1996)).

17.2.2 Oral health

Dental caries

In the absence of targe/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Key Points 17.1

Key Points 17.1

Key Points 17.2

Key Points 17.2 Key Points 17.3

Key Points 17.3 Key Points 17.4

Key Points 17.4