15

Two Famous People with Dental Connections

Paul Revere (American Patriot) and Bernard Cyril Freyberg (Soldier)

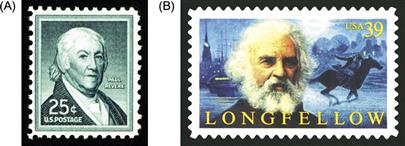

Two of the most famous people with strong dental connections are Paul Revere and Bernard Freyberg. Paul Revere’s exploits are known to every American, yet he is little known to the rest of the world. He must be the only ‘dentist’ whose image has appeared on a postage stamp, not once but twice: one a full portrait, the other commemorating the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, in which Revere is seen in the background on a horse (Figure 15.1).

Figure 15.1 (A) Paul Revere 1958 commemorative U.S. stamp. (B) Henry Wadsworth Longfellow 2007 commemorative U.S. stamp, with Paul Revere on horseback in the background.

Source: (A) from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paul_Revere_1958_Issue-25c.jpg. This work is in the public domain in the United States because it is a work of the United States Federal Government under the terms of Title 17, Chapter 1, Section 105 of the U.S. Code.

Bernard Freyberg is now virtually unknown outside of his homeland of New Zealand, yet if his life story were written as a novel, his adventures would be considered unbelievable.

Paul Revere (1734–1818)

Paul Revere (Figure 15.2) was born in Boston at the end of 1734. His father (original name Rivoires) was a French Huguenot who, like many others, had fled France to avoid religious persecution by the Catholic state. The town of Boston at that time had a population of about 15,000, made up of many people, such as Calvinists, Puritans and Quakers, who were also fleeing persecution. The people were proud of their independence and desired self-government, inevitably leading to conflict with Britain, whose Parliament and King George III, governed them from London.

Figure 15.2 Paul Revere.

Source: Photograph ©2012 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Revere’s father was a silversmith, and on his death in 1754, Paul, then aged 19, followed in his father’s profession and took over the family business. During this early period in the colonisation of North America, there was conflict between England and France, with both countries vying for dominance, as well as fighting with the indigenous Indian population. In 1756, Revere enlisted in the British Army and saw action against the French.

After his return to Boston, Revere completed his apprenticeship, became a master silversmith and married in 1757. His work was much in demand for the quality of his craftsmanship. During his lifetime he was to create more than 5000 silver items, producing some of the most valuable pieces of the period. One of his finest was the ‘Liberty Bowl’, reproductions of which are commonly called ‘Revere’ bowls. It was commissioned in 1768 and commemorates the refusal of the Massachusetts legislature to support a British tax. This was created in response to an early episode in the fight for independence.

In 1761, in order to increase and diversify his income, Revere’s skills were turned towards copperplate engraving, which he soon mastered. These engravings became very popular and were produced in very large numbers throughout his life, many with a political slant created as propaganda against British rule. Although somewhat unusual for an artisan, through his many diverse talents, clients and freemasonry, Revere became a well-known and respected figure in Boston society, mixing with influential political figures such as Dr Joseph Warren, John Hancock and Sam Adams, all of whom were to figure prominently in the forthcoming struggle for American independence. Revere was an early activist in this movement, believing strongly that people had the right to be governed by laws of their own making.

Even though he was a master silversmith and engraver, the economy was struggling and Revere needed an additional source of income in 1768 to support his growing family. His solution was to enter the dental profession. This came about through his friendship with an English dentist named John Baker. Little is known about Baker’s early life or training, although he seems to have arrived in America in the early 1760s and was one of the earliest practitioners to call himself a ‘dental surgeon’. At that time, dentistry was a very primitive occupation, and the procedures on offer would have been tooth extraction, cleaning teeth and fitting false teeth. Baker is known through an advertisement placed in the Boston Gazette of 22 January 1768, informing patients that he would be leaving. It seems that Baker taught Revere how to replace natural teeth lost by trauma or disease with false ones. This entailed carving false teeth from ivory (mainly from hippopotamus ivory; see Chapter 2) and attaching them to existing teeth by wire or silk.

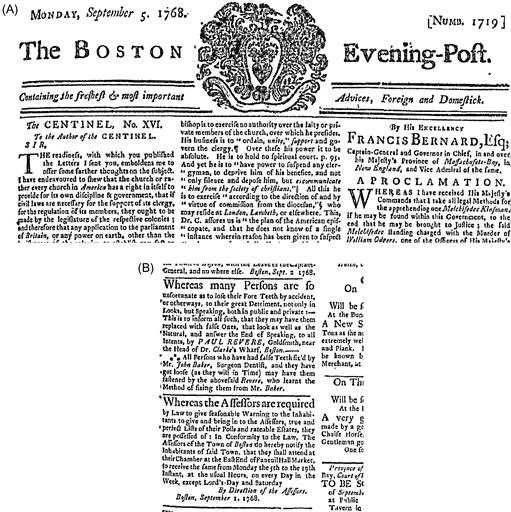

When Baker left Boston, Revere advertised his services in the Boston Gazette in September 1768 (Figure 15.3). It reads:

Whereas many persons are so unfortunate as to lose their foreteeth by accident, or other ways, to their great detriment, not only in looks, but speaking, both in public and private: this is to inform all such, that they may have them replaced with false ones, that look as well as the natural, and answer the end of speaking, to all intents, by Paul Revere, Goldsmith, near the Head of Dr Clarke’s wharf, Boston. All persons who have had false teeth fix’d by John Baker, Surgeon Dentist, and they have got loose (as they will in time) may have them fastened by the abovesaid Revere, who learnt the method of fixing them from Mr Baker.

Figure 15.3 (A) Header of Boston Gazette for September 1768. (B) Advert placed by Paul Revere.

Source: Courtesy of U.S. Library of Congress.

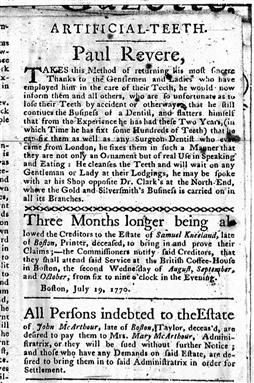

Nearly 2 years later, he placed another announcement in the Boston Gazette in July 1770 (Figure 15.4). Under the heading ‘Artificial Teeth’ it reads:

Paul Revere takes this method of returning his most sincere thanks to the gentlemen and ladies who have employed him in the care if their teeth, he would now inform them and all others, who are so unfortunate as to lose their teeth by accident or otherwise that he still continues the business of a dentist, and flatters himself that from the experience he has had these two years, (in which time he has fixt some hundreds of teeth) that he can fix them as well as any surgeon dentist who ever came from London, he fixes them in such a manner that they are not only an ornament but of real use in speaking and eating. He cleanses the teeth and will wait on any gentleman or lady at their lodgings, he may be spoke with at his shop opposite Dr Clark’s at the North End, where the gold and silversmith’s business is carried on in all its branches

Figure 15.4 Advert placed by Paul Revere in Boston Gazette, July 1770.

Source: Courtesy of U.S. Library of Congress.

Because Revere’s ledgers show items of dentistry up to 1774, it is clear that the practise of dentistry was a major occupation for him for at least 6 years. His patients even included his friend, Dr Joseph Warren, for whom he must have fixed a false tooth in the upper left canine region by gold wire (see page 215).

While he was practising dentistry, Revere may have indirectly benefited the profession by influencing the children of two neighbours, who were later to have a big impact on the American dental profession. One, Isaac Greenwood, had four sons, all of whom became dentists. John Greenwood supplied George Washington’s dentures and invented the first dental drill in 1790. The other neighbour was Josiah Flagg. His son, Josiah Flagg Jr (born 1763), was one of the first American-born dentists and may have constructed the earliest authentic dental chair in North America. He was also the first in a dynasty of dentists.

Politically, the 13 colonies in America had virtually no representation in the British Parliament, which made the laws and enforced the taxes. From the late 1760s, Boston was the centre for the colonists’ struggle for more independence from Britain. In 1768, Britain felt it necessary to send over extra troops to Boston for the purposes of intimidation and enforcement of legislation, including the payment of unpopular taxes. This move was seen by the colonists as inflammatory and stirred up unrest even further. The opposition was led by acquaintances of Revere such as James Otis, John Hancock and Dr George Warren, who realised the importance of forming links with other states and keeping them abreast of developments. Revere was completely sympathetic to, and an active supporter of, their views. Although never one for writing and making speeches, he was identified as a man of ability and integrity and, most importantly, an organiser who could get things done. Especially relevant was his unrivalled list of contacts in Boston, built up across all classes, in his capacity as a respected artisan, freemason and churchgoer.

In 1770, a small gathering of British troops, subjected to some hostility from the locals, fired into the crowd, killing five civilians. This incident, known as the Boston Massacre, led Revere to produce an engraving of a powerful illustration by Paul Walker, widely used as propaganda against the British.

The next major incident occurred in December 1773 when government officials tried to enforce a punishing tax on tea (to maintain the monopoly of this trade held by the East India Company). When three ships carrying a cargo of tea arrived in Boston Harbour, the colonists refused to pay the tax and demanded the tea be returned directly to Britain. Their slogan was ‘No taxation without representation’. Thousands of agitated townspeople gathered around Boston Harbour, and in the evening of December 16, a group of between 100 and 150 men boarded the ships, partly disguised as Mohawk Indians, and emptied all 342 tea chests into the water. Among the men was Paul Revere.

Following this revolt, and with signs of conflict growing daily, the colonist leaders in Boston felt it essential for the other states to be kept informed of what was happening in all parts of the country. Paul Revere was chosen for the important task of delivering the news of the revolt to the neighbouring cities of Philadelphia and New York. This he did in the only way then possible, on horseback. He covered the 700-mile round-trip in just 11 days. In the following 2 years, he would make at least five other similar journeys.

It was obvious that an intelligence network was required to spy and report on the activity of British troops. In addition, militia had to be organised and trained to be ready at very short notice (hence the term ‘minutemen’) to defend their homes and livelihoods against further British incursions. Revere, whilst still pursuing his varied business interests necessary to maintain and feed his ever-growing family (in his long life, he produced 16 children from two marriages), continued to ride back and forth with important news and instructions. He was more than just a messenger. He was involved in planning and decision making and was the ‘glue’ between disparate groups, especially between the politicians and the artisans, helping to produce a more cohesive force. While others talked, he acted!

Although their military forces were greatly outnumbered, the British government did not believe that the colonists could form a unified force to defeat their regular troops under the command of General Thomas Gage. The view was that as many of the colonists were British, they surely would not take up arms against their homeland. However, Britain would underestimate the colonists, many of whom already had experience in battle, having fought alongside the British against the French and local Indians.

The next major incident took place at the beginning of September 1774, when General Gage started to enforce the policy of disarming the population. He sent Lieutenant-Colonel George Madison with 260 British regulars to seize a large store of gunpowder from the Massachusetts Provincial Powder House, six miles from Boston. This proved a total success, taking the colonists completely by surprise.

By April 1775, it was abundantly clear from intelligence reports that the British were bent on crushing the independence movement in Boston, although the precise date of this intended action was not known. The colonists learnt of this not only from sympathisers in Britain but, more remarkably, probably also from General Gage’s own wife Margaret, who was American by birth. The plan was to arrest two of the leaders, Dr Sam Adams and John Hancock, at Lexington some 12 miles away. Following this, British forces were to march on a further six miles to the town of Concord and destroy the colonists’ main arms depot. General Gage did not think the colonists would resist. On learning of the plan, Dr Warren sent Revere to Concord on April 15 to warn them of a possible raid and instruct them to hide their arms and gunpowder.

There were two alternative routes the British could take: a longer, overland one or a shorter, sea route after being ferried across the nearby Charles River. Once the route was known and the British troops prepared to march, it was to be signalled using lanterns from the highest vantage point, the tower of Christ Church, to colonist lookouts across the river in Charlestown: one light for the land route and two lights for the sea route.

All the intelligence eventually pointed to a river crossing, commencing on the evening of April 18. Two lights were signalled for a brief moment from the tower of Christ Church. With the knowledge that about 700 British troops were beginning to move on Lexington by the sea route, Dr Warren instructed Revere to ride to Lexington. He was to take the quicker, sea route, and in case he did not succeed, another rider, William Davies, was sent by the longer, land route. The mission of both riders was to spread the alarm that the British regulars were on the way and to help Sam Adams and John Hancock avoid arrest. No instructions were given to them to ride on to Concord. At 10 pm on the evening of July 18, Revere left to carry out his regular duty of messenger, unaware that his journey would establish his place in American history. Although many may think that his epic ride to warn of the British advance was carried out by him single-handedly, at every stage along the route others were incorporated in spreading the alarm.

Revere was first rowed across the narrow Charles River on a clear moonlit night, under the 64 guns of the British warship Somerset. Luckily, he was not spotted and landed at Charlestown at 11 pm. Here, other friends provided him with a fine, strong horse named Brown Beauty. Encountering a British patrol deliberately deployed to prevent messages of British intent getting through, Revere was able to outride them and escape. He arrived at Lexington at 12 pm, warning people along the route, who spread the message by additional riders, church bells, gunfire and bonfires that the British regulars were coming. The colonist militias were rapidly mustered and rushed to defend Lexington and Concord and, if necessary, to fight the British.

Having arrived at Lexington, Revere passed on the warning to Samuel Adams and John Hancock that they should flee from the British. Further alarms were spread widely from Lexington.

William Dawes, the second rider, arrived in Lexington soon after Revere. History shows that, compared to Revere, his ride had little effect in spreading the alarm. Dawes was not a ‘connector’, lacking Revere’s rare social gifts and list of contacts, a phenomenon identified in Malcolm Gladwell’s book The Tipping Point. Revere’s unique role was the result of his long association with the politicians of Massachusetts: he knew who they were and where to find them, and they in turn had complete trust in his word. One can only surmise how history might have been affected had Revere not reached Lexington.

Just before 1 am, Revere and Dawes decided to ride on to Concord, to reinforce the warning of the oncoming British troops. They were joined by a third rider, Dr Samuel Prescott, but shortly after leaving Lexington, they were apprehended by a British patrol. Dawes and Prescott evaded capture and Prescott succeeded in reaching Concord, where further riders were despatched. Revere was eventually released about 3 am, but his horse was confiscated. He walked back to Lexington without ever reaching Concord. Brown Beauty was never seen again.

On returning to Lexington, Revere found Adams and Hancock still there and had to persuade them that they were too important to take part in the fight. He escorted them on their way out of Lexington to seek shelter in the nearby countryside. Revere’s final task was to rescue Hancock’s heavy trunk, which was full of important documents. It was about 4:30 am as he carried out this rescue that he witnessed the early stages of the next dramatic event.

The advanced column of British troops, numbering about 400, reached Lexington Village Common, with the officers in the rear. At this time, about 60 to 70 armed militia were present in Lexington under the command of Captain John Parker. They had no plan of action but decided to confront the British rather than retreat. It was important to the colonists in any ensuing struggle that they should not be the ones to fire first. In this way, if fighting broke out, they would not be morally responsible for starting it.

The British troops were headed by an inexperienced marine officer, Lieutenant Jesse Adair. Marching towards the small detachment of colonist militia ahead of him, he had the option of turning left and avoiding them or turning right and meeting them head on. In the absence of anyone senior, he made the fateful decision to turn right in battle formation, seemingly ready to confront the colonists. He was joined by some of his own mounted officers. With the two forces now separated by only about 20 m, a cool head at the front of the British column might still have been able to take control and diffuse the situation before anything serious happened. At this critical moment, a shot rang out. No one knows who fired it, but the response of the young and nervous British regulars was to begin firing, even though no order had been given. There was little return of fire by the colonist militia, who rapidly dispersed from the scene.

When news of the shooting reached farther down the British line to its leader, Colonel Smith, he immediately ordered his troops to cease fire. The result of this one-sided action was that seven militia men were killed and nine wounded: the British suffered just one soldier wounded. Although none of the participants was aware of its significance at the time, in historical terms this incident marks the first battle in the American War of Independence. It was now about 5 am on April 19.

Following the clash on Lexington Village Common, the British troops searched in vain for Adams and Hancock. They then moved on to Concord to seek out arms and ammunition, the main purpose of the mission. Now that the advantage of surprise had been lost, they realised their chances of success were low. With growing evidence of the increasing numbers of opposition forces, Smith sent back to Boston for reinforcements.

Earlier that morning, a messenger had been dispatched from Concord to Lexington to assess the progress of the British troops, and after witnessing the battle, he returned to alert the town. As the British marched towards Concord, initially they outnumbered the militia. The town was evacuated but the militia held a strong defensive position in the surrounding hills. On arriving in Concord, the British regulars had little success in their search for weapons and gunpowder. By now militia numbers had grown considerably, and in one area they outnumbered a British detachment of about 100 troops guarding a bridge. They advanced on this position, and when the British troops fired first, killing one or two of them, they returned this fire, killing and injuring a number of British troops. Most remarkably, the militia witnessed the British troops retreating in disarray.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses