Preventive Dentistry

Learning Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to achieve the following objectives:

• Pronounce, define, and spell the Key Terms.

• Explain the goal of preventive dentistry.

• Describe the components of a preventive dentistry program.

• Describe why dental care is important for pregnant women.

• Describe the method used to clean a baby’s mouth.

• Describe when children should first visit the dentist.

• Describe the effects of water fluoridation on the teeth.

• Identify sources of systemic fluoride.

• Assist patients in understanding the benefits of preventive dentistry.

• Discuss techniques for educating patients in preventive care.

• Discuss three methods of fluoride therapy.

• Describe the effects of excessive amounts of fluoride.

• Describe the purpose of a fluoride needs assessment.

• Describe the technique for application of fluoride varnish.

• Explain the steps involved in analyzing a food diary.

Performance Outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, the student will be able to meet competency standards in the following skills:

• Apply a topical fluoride gel or foam competently and effectively.

Electronic Resources

![]() Additional information related to content in Chapter 15 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

Additional information related to content in Chapter 15 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

![]() and the Multimedia Procedures DVD

and the Multimedia Procedures DVD

Key Terms

Dental sealant Coating that covers the occlusal pits and fissures of teeth.

Disclosing agent Coloring agent that makes plaque visible when applied to teeth.

Fluoride varnish Method of administration of topical fluoride.

Pontic (PON-tik) Artificial tooth that replaces a missing natural tooth.

Preventive dentistry Program of patient education, use of fluorides, application of dental sealants, proper nutrition, and plaque control.

Systemic fluoride Fluoride that is ingested and then circulated throughout the body.

Topical fluoride Fluoride that is applied directly to the tooth.

The goal of preventive dentistry is to help people of all ages attain optimal oral health throughout their lives. To achieve this goal, dental professionals must work together with their patients to prevent new and recurring disease. As was discussed in Chapters 13 and 14, various types of bacteria found in dental plaque are responsible for dental caries and periodontal disease, the two most common dental diseases.

The information provided in this chapter will help you to educate patients on how to achieve and maintain their oral health.

Partners in Prevention

To prevent dental disease, a partnership must be formed between the patient and the dental healthcare team. As a dental assistant, your first step is to help patients understand what causes dental disease and how to prevent it. The next step that you must follow is to motivate patients to change their behaviors and become partners in recognizing and preventing dental disease in themselves and their families. For example, mothers can be taught to simply lift their children’s lips to look for any stains, white spots, or dark areas on the teeth (Fig. 15-1).

Optimal oral health can become a reality when partners work together in a comprehensive preventive dentistry program that includes the following (Table 15-1):

TABLE 15-1

Comprehensive Preventive Dentistry Program

| Component | Description |

| Nutrition | Dietary counseling extends beyond the narrow scope of limiting sugar consumption and may include a discussion of nutrition from the standpoint of oral health and general health. |

| Patient education | Education motivates patients, provides them with information, and assists them in developing the skills necessary to practice good oral hygiene. |

| Plaque control | Daily removal of bacterial plaque from the teeth and adjacent oral tissues. |

| Fluoride therapy | Includes professionally applied fluorides, at-home fluoride therapy, and the consumption of fluoridated community water. |

| Sealants | Sealants are most frequently applied to the difficult-to-clean occlusal surfaces of the teeth. Decay-causing bacteria are then prevented from reaching into occlusal pits and fissures. |

Early Dental Care

Pregnancy and Dental Care

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) guidelines advise all pregnant women to receive counseling and oral healthcare during pregnancy, and that infants undergo oral health assessment by their first birthday. Many women are not aware of these guidelines and do not seek dental care during their pregnancy because they believe that they do not have any dental problems. However, dental care is an important aspect of total prenatal care. When the mother has a healthy mouth and teeth, she is protecting her unborn child. Untreated tooth and periodontal disease can increase the risk of giving birth to a preterm, low-birth-weight baby. Pregnant women should ask their dentist about using an antibacterial mouth rinse and chewing gum or eating mints that contain xylitol to reduce the bacteria in their mouth that cause tooth decay. This is very important because tooth decay is caused by bacteria that a new mother can transfer to her infant.

Dental Care for 0 to 5 Years

Good oral health for a lifetime begins at birth. Even before the baby has teeth, the parent should wipe the gums gently with a clean wet cloth after each feeding. To avoid spreading bacteria that cause caries, the parent should not put anything into the baby’s mouth that has been in his or her own mouth, including spoons, cups, and so forth.

As soon as the first tooth appears, the parent can begin brushing the baby’s teeth in the morning and before bedtime (Fig. 15-3, A). A pea-sized dab of toothpaste across a small soft brush can be used. Excess toothpaste should be wiped off. The baby should never be put to bed at naptime or at bedtime with a bottle or sippy cup unless it has only water in it, because milk and juices cause early childhood caries, which is also known as “baby bottle tooth decay.”

A baby should visit the dentist by the time of his or her first birthday and thereafter as often as the dentist recommends (Fig. 15-3, B).

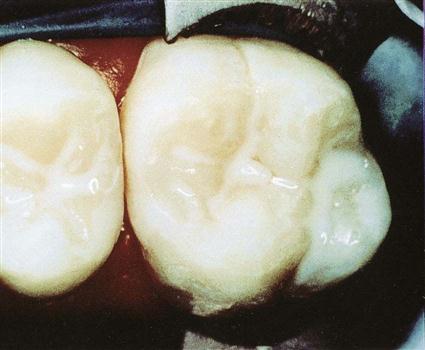

Dental Sealants

A dental sealant is a plastic-like coating that is applied over the occlusal pits and grooves of the teeth. Sealants are used to protect difficult-to-clean occlusal surfaces of the teeth from the bacteria that cause decay (Fig. 15-4).

Dental sealants are an important component in preventive dentistry. In several states, the application of dental sealants is delegated to the dental assistant as an expanded function (see Chapter 59).

Fluoride

Since the 1950s, fluoride has been the primary weapon used to combat dental caries. Slowing demineralization and enhancing remineralization of tooth surfaces are now considered to be the most important ways that fluoride controls the caries process (see Chapter 13).

Fluoride, sometimes referred to as “nature’s cavity fighter,” is a mineral that occurs naturally in food and water. To achieve the maximum cavity prevention benefit of fluoride, an ongoing supply of both systemic and topical fluoride must be made available throughout life. According to the patient’s needs, various ways are available to receive fluoride therapy, including the following:

• Prescription-strength fluorides that are applied in the dental office

• Nonprescription-strength, over-the-counter products for home use

• Consumption of fluoridated bottled water or community water

Systemic fluoride is ingested in water, food, beverages, or supplements. The fluoride is absorbed through the intestine into the bloodstream and is transported to the tissues where it is needed. The body excretes excess systemic fluoride through the skin, kidneys, and feces.

Topical fluoride is applied in direct contact with the teeth through the use of fluoridated toothpaste, fluoride mouth rinses, and topical applications of rinses, gels, foams, and varnishes (Fig. 15-5).

How Fluoride Works

Preeruptive Development

Before a tooth erupts, it is surrounded by a fluid-filled sac. The fluoride present in this fluid strengthens the enamel of the developing tooth and makes it more acid resistant.

Before birth, the source of systemic fluoride is the mother’s diet. After birth and before the teeth erupt, the child ingests systemic fluoride.

Posteruptive Development

After eruption of teeth, fluoride continues to enter the enamel and strengthen the structure of the enamel crystals. These fluoride-enriched crystals are less acid soluble than is the original structure of the enamel.

After eruption, an ongoing supply of fluoride from both systemic and topical sources is important for the remineralization process.

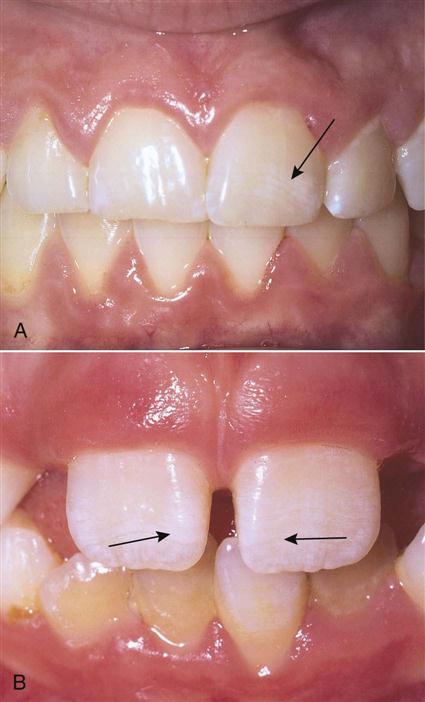

Safe and Toxic Levels

Fluorides used in the dental office have been proved to be safe and effective when used as recommended. Chronic overexposure to fluoride, even at low concentrations, can result in dental fluorosis in children younger than 6 years with developing teeth (Fig. 15-6). Abuse of high-concentration gels or solutions of fluoride or accidental ingestion of a concentrated fluoride preparation can lead to a toxic reaction. Acute fluoride poisoning is rare.

Precautions

To protect patients from receiving too much fluoride, current fluoride intake should be evaluated. For example, a child may live in an area with community water fluoridation, attend a preschool with a fluoride rinse program, and use a fluoride toothpaste at home. The dentist will consider these multiple sources of fluoride before prescribing additional fluoride supplements or office treatments for this child.

A particular area of concern involves young children, who may consume excessive fluoride by swallowing fluoridated toothpaste, which may cause fluorosis. Adult supervision of young children during toothbrushing is necessary, and the child should be instructed not to swallow the toothpaste. Fluoride in drinking water, fluoride toothpaste, fluoride rinses, and professionally applied treatments provide a cumulative effect, and the amount taken in should be monitored.

Fluoride Needs Assessment

A “fluoride needs assessment” is often used to help patients become more involved in their caries prevention program. The clinician who performs this assessment strengthens the dental partnership process by gathering relevant information from the patient and then helping the patient understand why fluoride is important and how it plays a role in the risk for future caries. Use of the fluoride needs assessment provides the following advantages:

Sources of Fluoride

Fluoridated Water

Until recently, it was believed that water fluoridation was effective in preventing tooth decay through systemic uptake and incorporation into the enamel of developing teeth. It has now been proved that the major effects of water fluoridation are topical and not systemic. Topical uptake means that the fluoride diffuses into the surface of the enamel of an erupted tooth rather than only being incorporated into unerupted teeth during development.

For more than 50 years, fluoride has been safely added to communal water supplies. Most major cities in the United States have fluoridated water, and efforts to fluoridate water in communities without fluoridation are ongoing. From a public health standpoint, fluoridation of public water supplies is a good way to deliver fluoride to lower socioeconomic populations that may not otherwise have access to topical fluoride products such as fluoridated toothpaste and mouth rinses.

Approximately one part per million (ppm) of fluoride in drinking water has been specified as the safe and recommended concentration to aid in the control of dental decay. In January 2011, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) recommended lowering the recommended concentration of fluoride from a range of 0.7-1.2 mg/L to a flat 0.7 mg/L. This concentration will provide the best balance of protection from dental canes while limiting the risk of dental fluorosis. This is the first change in HHS’s position on fluoride in nearly 50 years.

Levels of fluoride provided through controlled water fluoridation are so low that there is no danger that an individual will ingest an acutely toxic quantity of fluoride in water. Communities in some states, however, have water that naturally contains more than twice the optimal level of fluoride, and fluorosis is often seen in patients who live in these areas (see Chapter 17).

Bottled Water

Although many people consume bottled water, they may not realize that bottled water may not be equal to tap water with regard to dental health. The reason is the level of fluoride in bottled water. Some bottled waters may contain fluoride; however, most are below the optimum level of fluoride (0.7 to 1.2 ppm). The amount of fluoride in bottled water depends on the fluoride content of the source water, the treatment the source water receives before bottling (such as reverse osmosis or distillation), and whether fluoride additives were used. Currently the FDA does not require the bottler to list the amount of fluoride content on bottled water.

Sources of Systemic Fluoride

Foods and Beverages

Because many processed foods and beverages are prepared with fluoridated water, they must be considered a source of dietary fluoride in children who drink them regularly. In addition, many brands of bottled water contain fluoride. Persons who want the benefits of fluoride must be sure to check labels.

Prescribed Dietary Supplements

The dentist may prescribe dietary fluoride supplements in the form of tablets, drops, or lozenges for children ages 6 months to 16 years who live in areas with no source of fluoridated water (Fig. 15-7). Before prescribing supplements, the dentist considers the following factors:

Sources of Topical Fluoride

Topical fluoride is available in home care products such as fluoridated toothpastes and mouth rinses, as well as in professional topical fluoride applications used in the dental office (Fig. 15-8;

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Patient Education

Patient Education