Disorders of the temporomandibular joint

15.1 Anatomy and examination

Anatomy

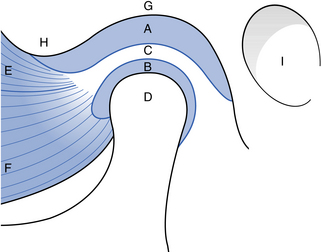

The TMJs are the two joints between the mandible and the temporal bones. They are unique in the body in that they contain two joint spaces separated by a fibrocartilage disc (Fig. 15.1).

Fig. 15.1 The structure of the temporomandibular joint.

(A) Upper joint space; (B) lower joint space; (C) interarticular disc; (D) condylar head; (E) lateral pterygoid muscle superior head; (F) lateral pterygoid muscle inferior head; (G) mandibular fossa; (H) articular eminence; (I) external auditory canal.

Components

The mandibular condyle: The mandibular condyle is a bony ellipsoid structure attached to the mandibular ramus by an elongated neck. Its mediolateral dimension (around 20 mm) is larger than the anteroposterior dimension (8–10 mm). Its articulating surface is covered in a thin layer of fibrocartilage. There is usually a clearly demarcated ridge running mediolaterally along its anterior surface. This is the edge of the articulating surface. Below the ridge is a hollow, marking an attachment of the lateral pterygoid muscle.

The mandibular (glenoid) fossa: The mandibular fossa is a hollow on the inferior surface of the squamous temporal bone. The fossa is bounded anteriorly by a ridge of bone, the articular eminence, which forms the anterior margin of the joint. The fossa is covered in a thin layer of fibrocartilage. The mastoid air cells often extend into the bone of the articular eminence and the bone of the fossa.

Interarticular disc: The interarticular disc is a biconcave sheet of avascular fibrous connective tissue that divides the joint into a superior and inferior joint space. At its anterior margin, it blends with fibres of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Posteriorly, it attaches to looser connective tissue (bilaminar zone) containing nerves and lined with synovial membrane.

Capsule: The TMJ has a fibrous capsule attached to the rim of the mandibular fossa and the neck of the condyle. The disc attaches to it medially and laterally. The lateral aspects of the capsule are thickened by the lateral (temporomandibular) ligament.

Ligaments: The lateral ligament lies lateral to the TMJ and runs from the root of the zygoma to the posterior aspect of the condylar neck. It limits anteroposterior joint movement. The sphenomandibular and stylomandibular ligaments are also part of the joint complex and probably also serve to limit movement.

Examination

The dental examination should be systematic and include the TMJ and the masticatory muscles.

Muscle examination: Muscle tenderness suggests some abnormal function (clenching, bruxism). Masseter and temporalis muscles are assessed by direct palpation. The lateral pterygoid is indirectly examined by noting the response (in terms of any preauricular pain) to attempted opening against the restriction of the examiner’s hand below the chin. The medial pterygoid cannot be examined.

Radiology

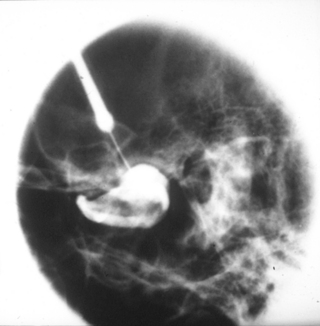

A clinical diagnosis of suspected internal derangement might lead to a requirement for imaging of the disc. This is done by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 15.3). TMJ arthrography (Fig. 15.4) is mainly of historical interest, but may occasionally be used where patients are unsuitable for MR examination, e.g. because of severe claustrophobia.

Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy allows visual examination of the upper joint space and an opportunity for minor surgical treatment. A small arthroscope can be used to facilitate lavage and division of joint adhesions. The lower joint space is difficult to access without risk of damage to the articular disc. Arthroscopy is undertaken under local anaesthesia; however, if lengthy arthroscopic surgery is to be undertaken, then a conscious sedation technique would be appropriate or even general anaesthesia.

15.2 Common disorders of the joint

Pain/dysfunction

Internal derangement

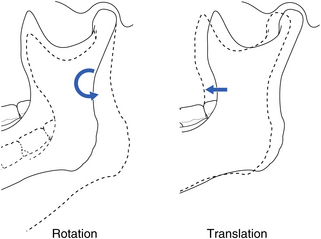

The articular disc normally sits above the anterior aspect of the condylar head, with the disc posterior attachment lying within 10° of the vertical (Fig. 15.5). A disc may be anterior to this ‘normal’ position in asymptomatic individuals, suggesting that an anterior disc position is a normal variant. Thus, an internal derangement is best thought of as an abnormality in position that interferes with function and that may be associated with other symptoms. An anterior disc ‘displacement’ is the most common internal derangement, but anteromedial, medial, and anterolateral displacements are all seen.

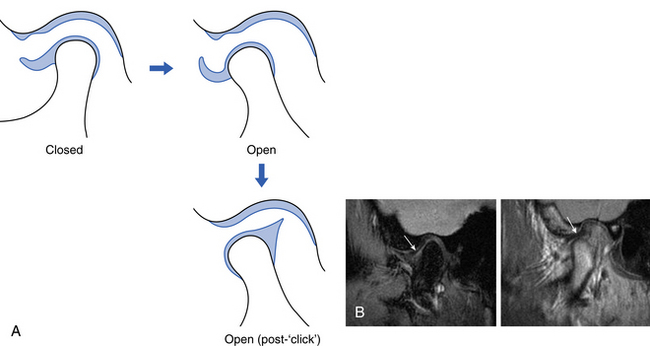

Disc displacement with reduction

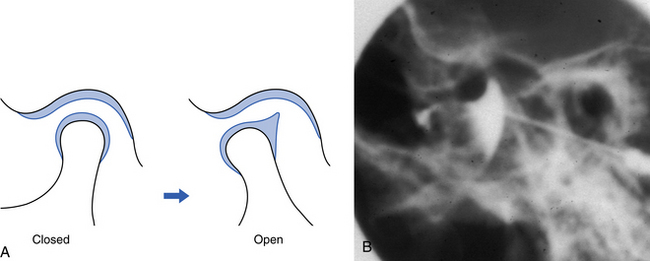

Reduction means that a displaced disc ‘reduces’ into a normal position on opening but reverts to an abnormal position on closing (reciprocal click) (Fig. 15.6A).

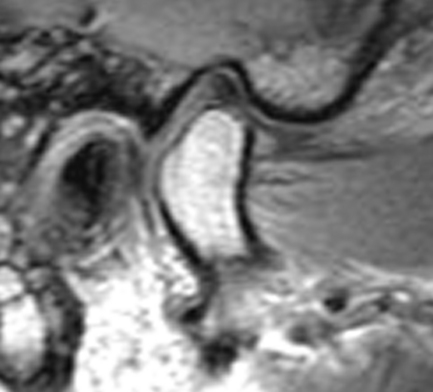

Fig. 15.6 A displaced disc with reduction showing the movement diagrammatically (A) and on MR in closed and open positions (B).

On the ‘open’ MR scan, the disc now lies above the condyle in a normal position.

Radiology

No abnormalities are apparent on plain radiographs. MR imaging shows the displaced disc in a closed/rest position (Fig. 15.6B).

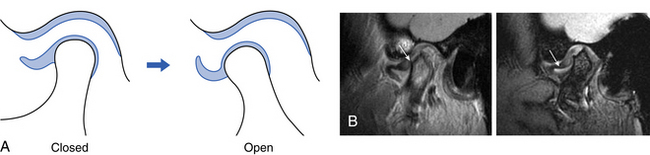

Disc displacement without reduction

If there is no reduction, a displaced disc remains in a displaced position regardless of the stage of opening. This interferes with movement and may cause pain (Fig. 15.7A).

Fig. 15.7 A displaced disc without reduction showing the movement diagrammatically (A) and on MR in closed and open positions (B).

Note that the disc is crumpled up in front of the condyle and the limited anterior translator movement of the condyle.

15.3 Other conditions affecting the joint

Osteoarthrosis

Osteoarthrosis is a non-inflammatory disorder of joints in which there is joint deterioration with bony proliferation. The deterioration leads to loss of articular cartilage and bone erosions. The proliferation manifests as new bone formation at the joint periphery and subchondrally. It has an unknown aetiology, but previous trauma, parafunction and internal derangements are all suggested as aetiological factors.

Radiology

Plain films show erosions of the articular surfaces of the condyle and, less commonly seen, of the mandibular fossa. Sclerosis of the bone and marginal bony proliferation (‘lipping’ or osteophytes) are seen (Fig. 15.8) and narrowing of the radiographic joint space. Bony proliferations may break away and be seen as loose bodies in the joint space.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses