14 Salivary gland disease

ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE

It is assumed that at this stage you will have knowledge/competencies in the following areas:

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

APPLIED ANATOMY

Parotid gland

The parotid gland is the largest of the salivary glands. There is considerable variation in size between individuals but for any individual both sides are similar. Although embryologically the parotid consists only of a single lobe, it is convenient to speak of a superficial lobe (superficial to the plane of the branches of the facial nerve) and a deep lobe (deep to that plane). The superficial lobe of the parotid is limited laterally by the preparotid fascia and overlying fat and skin. The zygomatic arch and temporomandibular joint is superior, the masseter muscle is anterior and posteriorly are the cartilaginous external auditory meatus, the mastoid process and the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The isthmus of the parotid gland is bounded by the ramus of the mandible anteriorly and the posterior belly of the digastric behind. The deep lobe is related to the medial pterygoid anteriorly, the styloid apparatus posteromedially and the internal jugular vein. Its deep surface lies immediately superficial to the tonsillar fossa and neoplasms arising from the deep lobe often present as tonsillar masses. The trunk of the facial nerve arises from the stylomastoid foramen just behind the styloid process. It enters the posterior parotid and becomes rapidly more superficial before dividing into two divisions, the superior larger zygomaticotemporal and the smaller buccocervical division. The facial nerve then further divides into five main branches—temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular and cervical—as it passes forwards in a plane separating the superficial and deep lobes. The main collecting duct arises within the superficial lobe and passes horizontally forwards, parallel to the buccal branch in a direction corresponding to a line joining the tragus to a point midway between the alar and the commissure. The duct crosses the masseter muscle horizontally, then turns at right angles to pierce the buccinator muscle and enters the oral cavity at the parotid papilla opposite the second upper molar.

INFLAMMATORY DISORDERS

Viral

Mumps (Fig. 14.1) is the most common cause of acute painful parotid swelling affecting children. It is endemic in urban areas and spreads via airborne droplet infection of infected saliva. The disease starts with a prodromal period of 1 or 2 days, during which the child experiences feverishness, chills, nausea, anorexia and headache. This is typically followed by pain and swelling of one or both parotid glands. The parotid pain can be very severe and is exacerbated by eating or drinking. Symptoms resolve spontaneously after 5–10 days. In a classical case of mumps the diagnosis is based on the history and clinical examination: a history of recent contact with an affected patient and bilateral painful parotid swelling is sufficient. However, the presentation may be atypical or sporadic or have predominantly unilateral or even submandibular involvement. In this situation mumps-specific IgM can be identified in the serum as early as 11 days following original exposure to the virus. This antibody is also detectable in the saliva. One episode of infection confers lifelong immunity.

Bacterial

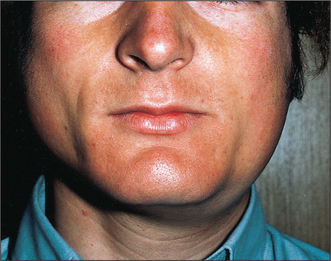

Acute ascending bacterial sialadenitis affects mostly the parotid glands (Fig. 14.2). Historically, it was described in dehydrated, cachectic patients often following major abdominal surgery when the patient was on a ‘nil by mouth’ regime. The reduced salivary flow and oral sepsis resulted in bacteria colonizing the parotid duct and subsequently involving the parotid parenchyma. With current hospital practice and improved oral hygiene, patients are rarely allowed to become dehydrated and this clinical pattern is uncommon. The typical patient presenting with an acute ascending bacterial parotitis now is an otherwise fit young adult with no obvious predisposing factors.

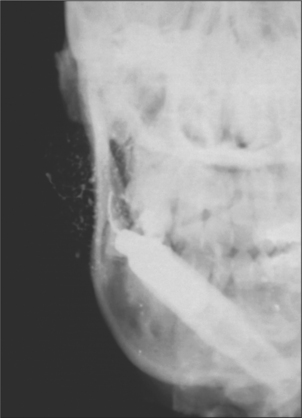

If the gland is gently ‘milked’ by massaging the cheek cloudy turbid saliva can be expressed from the parotid duct; this should be cultured. The infecting organism is usually Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus viridans. Sialography must never be undertaken during the acute phase of infection as the retrograde injection of infected material into the duct system will result in bacteraemia. Ultrasound imaging shows the characteristic dilatation of the acinae.

Recurrent parotitis of childhood

Recurrent parotitis of childhood exists as a distinct clinical entity but little is known regarding its aetiology and prognosis. It is characterized by the rapid swelling of usually one parotid gland, accompanied by pain and difficulty in chewing, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. Although each episode of parotid swelling is usually unilateral, the opposite side may be involved in subsequent episodes. Each episode of pain and swelling lasts for 3–7 days and is followed by a quiescent period of a few weeks to several months. Occasionally episodes are so frequent that the child loses a considerable amount of schooling. The onset is usually between 3 and 6 years, although it has been reported in infants as young as 4 months. The diagnosis is based on the characteristic history and is confirmed by sialography, which shows a very characteristic punctate sialectasis often likened to a snow storm against a dark night sky (Fig. 14.3).

‘Specific infections’ (granulomatous sialadenitis)

Swelling of the salivary glands may occasionally be caused by mycobacterial infection, cat-scratch disease, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, mycoses, sarcoid, Wegener’s and other granulomatous disease.

HIV-associated sialadenitis

Another presentation of salivary gland disease in HIV-positive patients is multiple parotid cysts causing gross parotid swelling and significant facial disfigurement. On imaging with CT or MRI the parotids have the appearance of a Swiss cheese, with multiple large cystic lesions (Fig. 14.4). The glands are not painful and there is no reduction in salivary flow rate. Surgery may be indicated to improve the appearance.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses