14

Prevention of Dental Phobia

Aetiology as the Background for Prevention

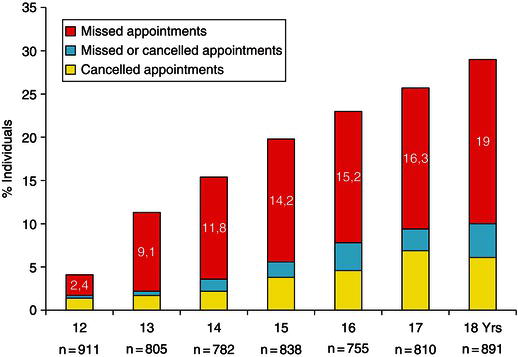

The multi-factorial aetiology of DA is outlined in Chapter 4. From a clinical perspective the factors are presented in a model consisting of three groups: personal factors, external/social factors and dental factors. In most cases dental anxiety (DA) and dental phobia (DP) have their origin in childhood and adolescence (Öst 1987). Children and particularly preschool children frequently display normal fear reactions and behaviour management problems (BMP) when exposed to new situations in the dental chair. Dental anxiety and dental phobia develop over time in a vicious circle of avoidance of care, leading to poor oral health and to negative self-conscious evaluations (feelings of inferiority, shame and embarrassment) (Berggren 1984) (see also Chapter 1). The model from dental anxiety to avoidance and poor oral health has also received support in recent studies (Armfield, Stewart and Spencer 2007; De Jongh, Schutjes and Aartman 2011). In a Norwegian study the frequencies of missed and cancelled appointments increased almost linearly during the age period from 12–18 years (Figure 14.1). Dental anxiety is one major factor related to this behaviour (Skaret et al. 1999) and the group with avoidance behaviour has reduced dental health at the age of 18 years compared to the non-avoiding group (Skaret et al. 1999). This supports the model and indicates a huge potential for prevention of recruitment to the vicious circle of avoidance among children and adolescents. However, there are few studies exploring the different factors and their efficiency to prevent development of dental anxiety. There is need for research using improved sampling, measurements and statistical approaches and that are based on longitudinal designs (Zhou et al. 2011).

Figure 14.1 Distribution of individuals with one or more missed or cancelled appointments during the age period 12–18 years of age. Modified from Skaret et al. 1998

Dental vulnerability

The personal factors and external/social factors, outlined in Chapter 4, represent the child’s individual vulnerability for being unable to cope with dental treatment. The child’s development is influenced by family, culture and social background. The ability to cope with new tasks is a balance between the child’s self-efficacy and the new challenges the child is facing, among these is dental treatment (Klingberg and Broberg 2007). To be able to diagnose a beginning avoidance behaviour and treat early signs of dental anxiety and BMP, we need to see the child in his/her total life situation. Some children are extremely robust in coping with new and challenging situations, whereas others are generally more vulnerable. It is a question about understanding the individual variations and adjusting for a possible mismatch between the need for treatment and the child’s ability of coping.

Dental factors

The two main factors, as described in Chapter 4, are painful dental procedures and lack of control. Based on the fact that the acquisition of dental anxiety and phobia most often seems to follow the theory of learning by classical conditioning (Davey 1989; Öst and Hugdahl 1985), these factors are regarded as the most important unconditioned factors. The dental treatment with its elements of uncontrollable pain and unpredictability also supports the cognitive vulnerability model of the aetiology of fear (Armfield 2006).

The sensation of pain is complex, as described later in this chapter. It is not necessarily dependent upon tissue damage; it may also be generated by conditioned stimuli such as the sound and vibration of the drill, smell, the touch of the explorer and other instruments. This implies that the use of effective local analgesia alone may not be enough for the prevention of painful experiences.

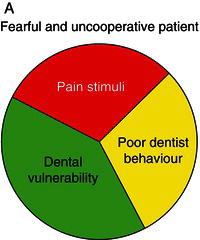

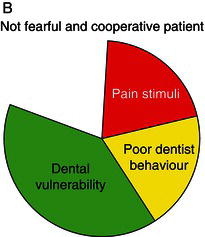

Figure 14.2 The figure illustrates the three major factors for a patient to develop fear and uncooperative behaviour in a dental situation. A: full circle means fear and uncooperative behaviour. B: partial circle means no fear and cooperative behaviour

Perceived lack of control may imply different aspects of the dental situation, e.g. insufficient information about the treatment procedures and the instruments used, feeling of being deprived the opportunities to stop the treatment if necessary and even lack of information and incitement to ask questions after the treatment. These situations typically occur when dentists are more occupied by accomplishing the dental treatment rather than taking care of the patient as a whole, being in a hurry and not communicating well with the patient.

Based on our knowledge about the influence of dental vulnerability and dental factors, as described above, a simple model for practical behaviour management is suggested (Figure 14.2). Since we are usually not able to change the personal and external/social factors (vulnerability) in the model, we must adapt the dental factors to the level of vulnerability since they represent a potential for prevention of behaviour management problems, dental fear and anxiety and dental phobia. In the two examples in Figure 14.2 (A and B) the patients’ dental vulnerability is similar (same size of dark grey sector). In example A, the pain stimuli and the dentist behaviour have not been adapted to the patients’ vulnerability (large black and light grey sectors), resulting in a totally filled circle, which illustrates generation of fear and uncooperative behaviour. In example B, the dentist has adapted his/her behaviour to the level of the patient’s vulnerability and placed emphasis on minimizing the painful stimuli (small black and light grey sectors). The circle is therefore not totally filled and the patient is able to cope with the treatment.

Since present knowledge on the aetiology of dental anxiety and phobia is complicated, as outlined in Chapter 4, the simplified model in Figure 14.2 may be useful for practitioners during dental treatment of individual patients in order to prevent development of dental anxiety disorders.

Dentist Behaviour

Establishing rapport

Independent of which treatment approach is used, treatment of fear and anxiety starts with establishing rapport. A trusting relationship between the patient and the dental personnel is basic both for prevention and treatment of dental phobia. General principles for good clinical communication, e.g. warmth, respect, empathic listening, autonomy and informed consent should guide every consultation with a patient.

The Four Habits Model is presented as an approach to the medical interview (Frankel and Stein 1999) and should be a guide also for the interview with the dental patient. The term Habits describes four patterns of behaviour, presented as: (i) Invest in the beginning; (ii) Elicit the patient’s perspective; (iii) Demonstrate empathy; and (iv) Invest in the end. The first few moments of the encounter are key elements for establishing a trusting relationship and the verbal and non-verbal signals given here will often affect the outcome of the visit (Frankel and Stein 1999). This moment may often be ignored or underestimated as being preliminary to the ‘business’ of the interview and the dental personnel are often focusing on the dental treatment too early (Frankel and Stein 1999). The anamnestic evaluation should always include a question like ‘Are you afraid of dental treatment?’ or ‘How unpleasant do you experience dental treatment?’ ‘Select a number on a scale from 1–10 that fits best for you, where 1 is not at all and 10 is very much’. A good response to a high fear rating could be that the dentist is giving comments and questions like:

- I have noticed that you don’t like to go to the dentist?

- Many people have the same view.

- Is there anything we could do to make it easier for you?

- What is it you dislike the most?

- What is the worst thing you fear will happen when you are in that situation?

- I suggest that we spend some time talking about this and find ways of doing the treatment that makes it easier for you.

Meeting the Child and the Parent in the Waiting Room

A good practice would be that every new patient is met in the waiting room by the dentist or the hygienist, depending on who is going to do the dental exam. If the new patient is a child he/she should be met with the same respect and the same principles as for an adult patient. The meeting starts with presenting yourself and clarifying your role (‘I am the dentist’), first to your child patient and then to the caretaker. The meeting in the waiting room may give lots of signs that will be helpful in the establishment of a trusting relationship. This moment is the start of a process aimed at establishing rapport and also the start of getting important information about the child and his/her life situation. Verbal and non-verbal signs may together provide such information – factors like personality, maturity, emotions and experiences. Children showing dental behaviour management problems may have a burdensome life and family situation (Gustafsson et al. 2007) and may give signals about parental style. Studies have shown that the child’s behaviour towards adults varies according to different parenting styles and that the behaviour continues in the dental office and may influence the complicated patient–parent–dentist interaction (Aminabadi and Farahani 2008). Research looking at the relationship between authoritative, permissive and authoritarian aspects of the caregivers’ parenting style and the child’s reaction to restorative dental procedures has shown preliminary evidence for a significantly more favourable behaviour during the procedure for children of authoritative parents compared to children of permissive and authoritarian parents (Aminabadi and Farahani 2008). The first meeting with the child and parent will provide valuable information for further communication. The psychologically more independent child of the authoritative parent has higher self esteem and will probably respond to the questions him/herself, whereas in other cases the same question more often will be answered by the parent.

Child and Parent in the Dental Clinic

The question whether or not the parent should accompany the child in the dentist’s office is controversial, probably because there is no absolute yes or no answer. Generally it is reasonable for a small child to have the parent accompanying him/her into the dentist’s room, especially if this is a new situation for the child, in order to reduce the child’s general fear. In addition, it is necessary for exchange of information between caregiver and dentist about both parties’ ideas of the situation. The parents have their own experiences with dental treatment. They have things they want to explain to the dental personnel. In addition the presence of the parents will give further indications about their parenting style and how the parent and child communicate. On the other side, the situation also allows the dentist/hygienist to present him-/herself and the treatment philosophy to the parents.

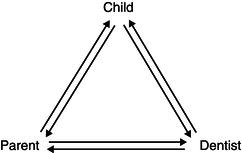

The conversation must include both the child and parent, as illustrated in Figure 14.3, in order to establish a trusting relationship with both of them. The figure shows the triangle of communication that will always exist and therefore must be considered. If, for example, the dentist has established an excellent communication with the child, but has neglected proper exchange of ideas with the parent, a possible negative attitude may be communicated from the parent to the child either during or after the session and the good relationship between dentist and child may be reduced. This means that we always have to ‘play on the same team’ as the parents. They will have their focus on the dental treatment needs and they have to be informed that the time needed for behaviour shaping is an investment for the future and not because their child is not brave enough.

These principles primarily apply to small children and the first treatment session(s). When a trusting relationship has been established with both child and parents, all parties usually appreciate that parents remain in the dental room. This is also often the case for older children and adolescents. There are, however, cases where it is preferable to depart from these major principles, e.g. when parents are interfering negatively with the treatment process and therefore must be dismissed. It is of major importance that this is done according to the rules of good etiquette in order to prevent the parent ruining a good relationship between dentist and child by negative communication with the child after the session.

Figure 14.3 Communication triangle

Behaviour Shaping

Behaviour shaping should be introduced early and if possible during sessions of preventive dentistry where no invasive treatment is yet needed. The reason for this is that positive experiences in the dental chair seem to be favourable in making children able to cope with more unpleasant and painful experiences later (latent inhibition; Davey 1989). Clinically, this means that giving a child several positive experiences with no invasive treatment will help the child to cope with future treatment. It also means that starting dental treatment with an invasive treatment session, e.g. extraction, represents a risk of lack of coping in the future.

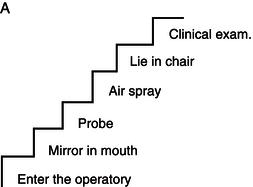

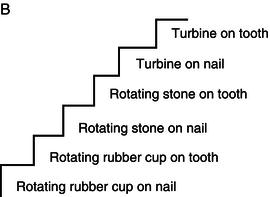

In cases with dental treatment needs beyond the child’s coping capabilities, the treatment should be postponed (if possible) until necessary behaviour shaping or the child is more mature. The behaviour shaping must aim at introducing the child to actual treatment needs, including how the instruments work and their purpose. Based on the individual child’s experiences and beliefs, the stimuli may be arranged in a stepwise fashion, in which each step represents a procedure or an instrument to be learned. The child will need time to explore and be familiar with the different instruments, and it is normal to be sceptical (Figure 14.4). Two examples of steps are illustrated in Figure 14.5, in which A is suitable for a young, inexperienced child to be examined for the first time and B is an introduction to the rotating instruments. After having explained the procedure to the child (and parent) in a comprehensive way, he or she is exposed to each stimulus in a sequence of potentially increasing fear. Each exposure is introduced by the use of the tell–show–do method. Before proceeding to the next stimulus the child must show positive acceptance in the present step. If not, the procedure must be repeated. The different steps must be adapted to the individual child and the situation. Introducing different instruments and procedures should also be done in situations where the child is curious and asking questions, even if the need for these specific instruments and procedures is not there yet. This child gives signs of need for information. For some patients the need for information is important and lack of response to their questions may increase the feeling of lack of control. These patients often like to look in the mirror. Having a hand mirror at their disposal gives a good feeling of control and being included in the ‘team’.

Figure 14.4 To be sceptical is normal. Photo: Håkon Størmer, University of Oslo

Figure 14.5 Behaviour shaping based on the exposure technique. A: Example of exposure steps for a child who is going to be clinically examined for the first time. B: Example of steps suitable for introduction to drilling

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy in Fearful Children and Adolescents

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a treatment approach shown to be very effective in treatment of dental phobia in adults (see Chapter 10). However, the basic principles of CBT may also be useful for prevention of dental phobia in clinical practice. The average age of onset for dental phobia is estimated to be 12 years (Öst 1987) and the prevention of this disorder must therefore have a high focus in dentistry for children and adolescents. In a literature review (Davis, Ollendick and Öst 2009) the authors conclude that CBT in children and adolescents follows the same basic principles as for adults and the present evidence shows that even more intensive treatment (one-session treatment of specific phobias, see Chapter 9) in children and adolescents is both efficient and efficacious. The treatment of lower levels of anxiety should therefore follow the same principles as for a phobic patient. However, children and adolescents are in many ways different from adults. They are immature and still under development. The approach has to be adjusted according to age and their capability for abstract thinking (Davis et al. 2009). The more intensive treatment (longer sessions) must also be adjusted to the age and maturity of the child and to signs indicating that the child has ‘used up’ his/her available time for that day.

Children are often brought to treatment by parents and the motivation for treatment may be the parents’ rather than the patient’s. A good outcome of CBT in children is dependent upon the child’s own motivation for being treated for the fear and thereby being able to cope with ordinary treatment. The pre-treatment interview to find out what maintains the individual patient’s phobia should also focus on the child’s own motivation (Öst 2010; Svirsky and Thulin 2010). To have a phobia may give secondary benefits that may decrease the motivation for phobia treatment. One example is a patient with intra-oral injection phobia where the future plan is orthodontic treatment including extraction of premolars. The injection phobia ‘protects’ against having to do extractions. In these cases it is important to tell the patient that teeth will never be extracted without his/her consent. This is independent of the ability to receive an injection.

The beliefs influence the subjective experiences of pain and anxiety

A patient’s fear response is often presented by three response systems: the physiological; the behavioural; and the cognitive/affective system (see Chapter 4). These responses will increase with higher levels of fear and become gradually stronger for anxiety and phobia compared to fear. To prevent anxiety or even phobia, it may be helpful for the dentist to have this model in mind. The physiological response is biological and functional in that it reminds us of a potentially harmful situation. The most frequent and strong response is increased heart activity and muscle tension while thinking of the dental situation (Hugdahl 1984) and during a dental examination (Öst and Hugdahl 1985). The patient’s interpretation of the meaning of this ‘motor’ (activation in the autonomic nerve system) is essentially related to whether or not he/she will have positive or negative thoughts when sitting in the dental chair.

Exploring the child’s’ negative thoughts

It is important for the dentist to explore the patient’s thoughts in the situation. What is the specific problem? As described in Chapters 9 and 10, the catastrophic beliefs are maintaining the avoidance behaviour. For children the catastrophic beliefs may be more unclear and more difficult to explore. They may also have another person’s beliefs as/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses